What ho, and all that.

Today’s post is one I have been meaning to do for a while – Glossop in the Domesday Book. I have been picking away at this one for a few months now, and finally I spent a bit of down time finishing it off. I must say I enjoyed writing it, and I really had to do some homework… which was fun. Hope you enjoy.

The ‘great survey’ of England (and parts of Wales) that would eventually become known as the Domesday Book was commissioned by William the Conquerer and completed in 1086. According to the Anglo Saxon Chronicle of c.1100, it was a survey of “How many hundreds of hides were in the shire, what land the king himself had, and what stock upon the land; or, what dues he ought to have by the year from the shire.“. In essence, what had William actually won in his new kingdom, and more importantly for him, how much he could make in taxes. I’m not a fan of old Billy, as you have probably guessed, and although Norman England brought with it some good, it also brought widescale changes throughout society – lay and secular – some of which were not particularly great. Academic argument rages, and will continue to do so, but I cannot forgive William the Bastard, as he was known (he was the illegitimate son of Robert I, Duke of Normandy, by his mistress Herleva), and even by the standards of his day he lived up to the other meaning of his name. But he did give us this unparalleled piece of historical evidence

Actually, the survey was undertaken and published in 2 parts – the ‘Little Domesday’, which covered Norfolk, Suffolk, and Essex, and the ‘Great Domesday’, which covered the rest of England and parts of Wales. Incidentally, the title Domesday Book, though not contemporary, is derived from the fact that the details recorded in it were as serious and as unmoving as the decisions made by God on the Day of Judgement – Doomsday. Also, as an interesting aside, my grandfather told me that he once had reason to be working at the Public Record Office in London, and that whilst there he found himself in the storeroom where the Domesday Book was then being kept. With a pound note pressed into his hand, the guard on duty opened up the high security box, and allowed my grandfather to place his own hand on the actual Domesday Book. But I digress…

So then, Glossop and area in the Domesday Book. The reference within the book is in Derbyshire, Chapter 1 (Land Belonging to the King), paragraph 30, and comes under the heading ‘Longdendale’.

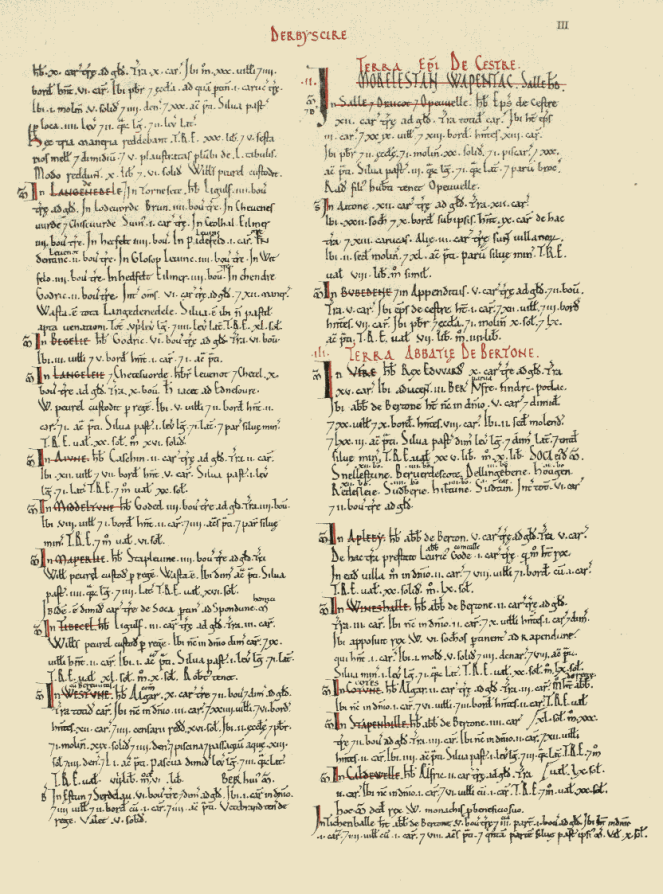

Here is the page:

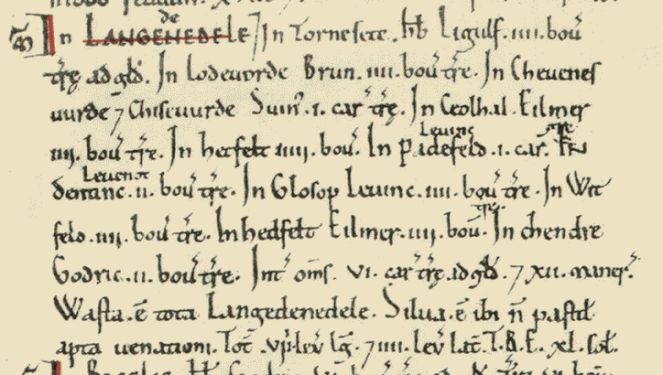

And here is Longdendale as it was recorded in the book:

The above image is courtesy of this phenomenal website which has digitised the whole Domesday Book, with all sorts of notes and details. Go and explore this fascinating document, and priceless item of English history.

I’ll give you the complete transcription, translate, and then discuss what it means.

In LANGEDENEDELE. In Tornesete. Hb. Ligulf. iiii bov. Tre ad Gld. In Lodeuorde, Brun. iiii bov. tre. In Cheuenesuurde Chiseuurde. Suin. i car. tre. In Ceolhal. Eilmer iiii bov. tre. In Hetfelt iiii bov. In Padefeld. Leofing i car. In Dentine. Leofnoth. ii bov. tre. In Glosop Leuine. iii. bov. tre. In Witfeld. iiii. bov. tre. In Hedfelt Eilmer. iiii. bov. tre. In Chendre. Godric. ii. bov. tre. Int. oms. vi. car. tre ad gld. Xii maner. Wasta. e tota Langedenedele. Silua. e ibi n pastit apta uenationi. Tot viii. leg lg. iiii. lev lat. T.R.E xl. sol.

- In Thornsett (Tornesete), Ligulf had 4 bovates of land that were taxable.

- In Ludworth (Lodeuorde), Brown (Brun) has 4 bovates of land that is taxable.

- In Charlesworth (Cheuenesuurde) and Chisworth (Chiseuurde), Swein (Suin) has 1 carucate of land that is taxable.

- In Chunal (Ceolhal), Aelmer (Eilmer) has 4 bovates of land that is taxable.

- In Hadfield (Hetfelt), Aelmer (Eilmer) has 4 bovates of land that is taxable.

- In Padfield (Padefeld), Leofing has 1 carucate of land that is taxable.

- In Dinting (Dentine), Leofnoth has 2 bovates of land taxable.

- In Glossop (Glosop), Leofing has 4 bovates of land that is taxable.

- In Whitfield (Witfelt), Leofing has 4 bovates of land that is taxable.

- In Hayfield (Hedfelt), Aelmer (Eilmer) has 4 bovates of land that is taxable.

- In Kinder (Chendre), Godric has 2 bovates of land that is taxable.

Phew! Right… so what on earth does that mean? Well, Longdendale (Langedenedele as the book has it) is first broken down into areas, then who owns these areas is recorded, followed by the amount of land that is taxable – the Domesday book is essentially a tax record of how much William stood to gain from the invasion, after all. However, here, recorded for the first time ever, are the names of the places we know well. And I am struck immediately by how similar they are… stick a decent Glossop accent onto them, and they haven’t changed at all – Whitfield and Hadfield in particular! And I love the Saxon names, too. Aelmer and Leofing are the big landowners around here with 1 1/2 and 2 carucates of land respectively, and so are probably quite wealthy and with good lands. Poor Godric is stuck out in the wilds around Kinder, where it is difficult to see where his 2 bovates of taxable land could be located. Which brings us on to the next question… what the hell is a bovate? Or, for that matter, a carucate?

They are both ancient measurements of land area. A bovate (also known as an oxgang) is technically the amount of land a single ox could plough in a single season – somewhere around 15 acres depending on land and animal. However, a plough is normally driven by a team of 8 oxen, and the amount this team could plough in a single growing season is known as a carucate. Thus, a bovate is one 8th of a carucate. Now, I struggle to picture area, so the idea of a large area defined by how much work an animal does is, quite frankly, baffling.

Following the register of places and taxes, there is a general description of the area.

- Between them 6 carucates of land is taxable, and 12 manors

Each of the 12 manors (the areas named above) would have had a manor house to go with it, and one wonders where they are. I have a few ideas, but there is no way of knowing without excavation. One can imagine Leofing, beer cup in hand, sitting on a chair in the centre of his house – effectively a large open hall in which multiple people ate, drank, slept and lived around a central fire pit, the smoke from which would have dissipated amongst the thatch or turf roof, as there were no chimneys in the 11th Century.

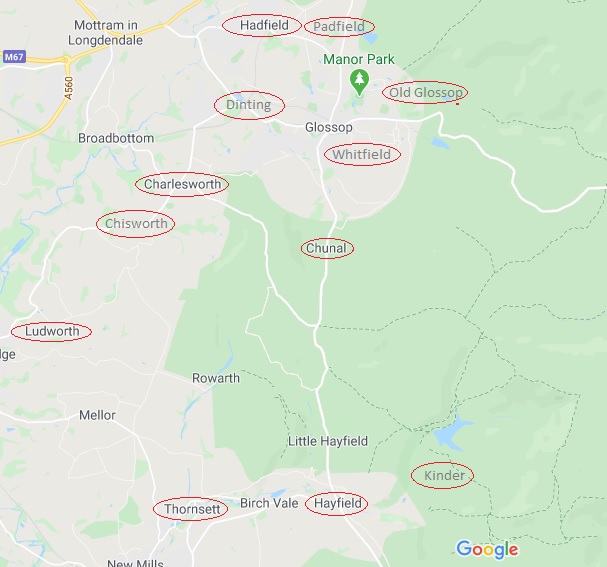

Looking at the above map, I am struck by two things. Firstly, how almost all of the manors are situated on major roads (Whitfield is on the old road to Glossop, before it was diverted to what is now Glossop town centre), and how they are all still recognisable and distinct places. The one glaring exception is Kinder, which ceases to be a ‘place’ as such after the Medieval period; one presumes that it is in the area of the houses and farms on Kinder Road, but further research is needed.

Then there is the single word ‘Wasta’. Waste.

- “All Longdendale is waste”.

Following the invasion of 1066, the North of the country – Cheshire, Derbyshire, Lancashire, Staffordshire, and Yorkshire – rebelled against the French king. William the Bastard chose to teach them a lesson over the winter of 1069-1070, and operated a ‘scorched earth’ policy of complete destruction of all villages, property, crops and people – the ‘Harrying of the North‘ as it is now known. There is some debate about the extent of the destruction, but there is no getting away from the fact that he utterly destroyed huge swathes of the North in revenge, and North Yorkshire in particular, with refugees from there mentioned as far away as Worcestershire. The effect was such that 16 years after the Harrying, Yorkshire had only 25% of the people and oxen that it had in 1066. The almost contemporary historian Ordericus Vitalis (basing it on contemporary descriptions) describes it thus:

“Nowhere else had William shown such cruelty… In his anger he commanded that all crops and herds, chattels and food of every kind should be brought together and burned to ashes with consuming fire, so that the whole region might be stripped of all means of sustenance. In consequence so serious a scarcity was felt in England, and so terrible a famine fell upon the humble and defenceless populace, that more than 100,000 Christian folk of both sexes, young and old, perished of hunger”

The word ‘Waste’ here in Longdendale is the result of this destruction – the valley, never particularly prosperous, or indeed populous, was laid waste… the Bastard burned the place to the ground. This is an astonishing fact, and that one word – waste – resonates. Indeed, as you read through the Domesday Book entries for the surrounding areas, the phrase crops up time after time “it is waste”.

Moving swiftly on.

Longdendale is then described as “woodland, unpastured, and fit for hunting” – which is better than some of the Trip Advisor reviews for places in Glossop – and the fact that it is “8 leagues long, and 4 leagues wide” (roughly 24 miles by 12 miles).

The entry in the Domesday Book finishes with letters “T.R.E. xl. sol.”. T.R.E. stands for ‘tempore Regis Edwardi’ – that is, in the time of the reign of Edward the Confessor, and refers to the worth of the land in the time immediately prior to the invasion. In 1066, Londendale’s worth (in terms of taxes) was 40 Shillings (represented in the book by the Roman numeral ‘XL’ for 40, and the abbreviation ‘sol’ for ‘solidus’ or shilling. 40 Shillings is not a lot, comparatively, and must surely represent the poor quality of arable land in these parts, as well as a lack of mineral resources.

Now, what is interesting, is what is left out. For example, there is no mention of people – freemen, villagers, smallholders, etc. – and we are left with the impression that there is no one here. Yet just over the hill, in Hope, we read that “30 villagers and 4 smallholders have 6 ploughs. A priest and a church to which belongs one carucate of land” and that “before 1066 these 3 manors paid £30, 5 1/2 sesters of honey, and 5 wagon loads of 50 lead sheets. They now pay £10 6s.” Clearly in Hope the invasion had had an effect – they now pay £20 less in tax, so one assumes there is less there now that is taxable – but there are people there, in 3 manors. So it seems odd, then, that Longdendale, despite having 12 manors, has no mention of people. It may be poor record taking by the surveyors, or it may be more sinister – Longdendale is the main route west out of Yorkshire, after all. The other oddity is that there is no mention of the church. It is possible that Glossop Parish Church is of Anglos Saxon origin, there is no evidence for this, and the lack of a mention in the Domesday Book is also quite telling. Which begs the question… where was the nearest church? Hope? That’s quite a journey to be made every Sunday, but I can’t think of anywhere else nearby.

So there we have it, Glossop’s debut in the historical record. One wonders where exactly Glossop was at the time – certainly not Howard Town, but perhaps Old Glossop. There is the suspicion that it may have been further out, toward Shittern Clough and Lightside along Doctor’s Gate, but again, we can’t be certain without excavation.

Anyway, I hope you enjoyed this little romp around Early Medieval Longdendale, As always, any comments, questions – or even abuse from pro-Norman activists – are all very welcome.

Until next time, I remain.

Your humble servant,

RH