What ho, wonderful denizens of the blog reading world! How are we all? Well this is something of a to-do… what? Two posts in February? Truly I am spoiling you. Well, it’s about time I picked up the pace a little! I actually had a choice of about 4 half finished articles that I was going to go with, and I actually started working on all of them at some point in the last few weeks before I plumped for this one. Anyway, I hope you enjoy it.

So, I recently discovered the glacial erratic on Pyegrove Park. Now, I should clarify… I didn’t actually ‘discover’ it – lots of people already knew it was there, and in fact I already knew it was there, it’s just that I’d never been able to find it. But the discovery got me thinking: this blog is about archaeology, that is the study of humans and their history through the physical remains they left behind. And yet where we are, and how we live, and indeed how we have lived, has been dictated to us through the landscape, and our place within this. In short, there would be no Glossop without Longdendale, and there would be no Longdendale without the glaciers. So wrap up well, people… we’re off the the ice age.

Ok, so some background, and not being a geologist I really had to put in the homework here, so you’d best appreciate it! Honestly, my brain only has so much space in it: I once learned to ice skate and forgot how to use a knife and fork. What follows then is the ‘back of a fag packet’ version of the last period of glaciation (and before we move on, I must give a massive shout out to a superb website which really helped iron out some of the trickier bits – AntarcticGlacier.org – fascinating, well written, and aimed at non-specialists… well worth checking out if any of this interests you even in the slightest).

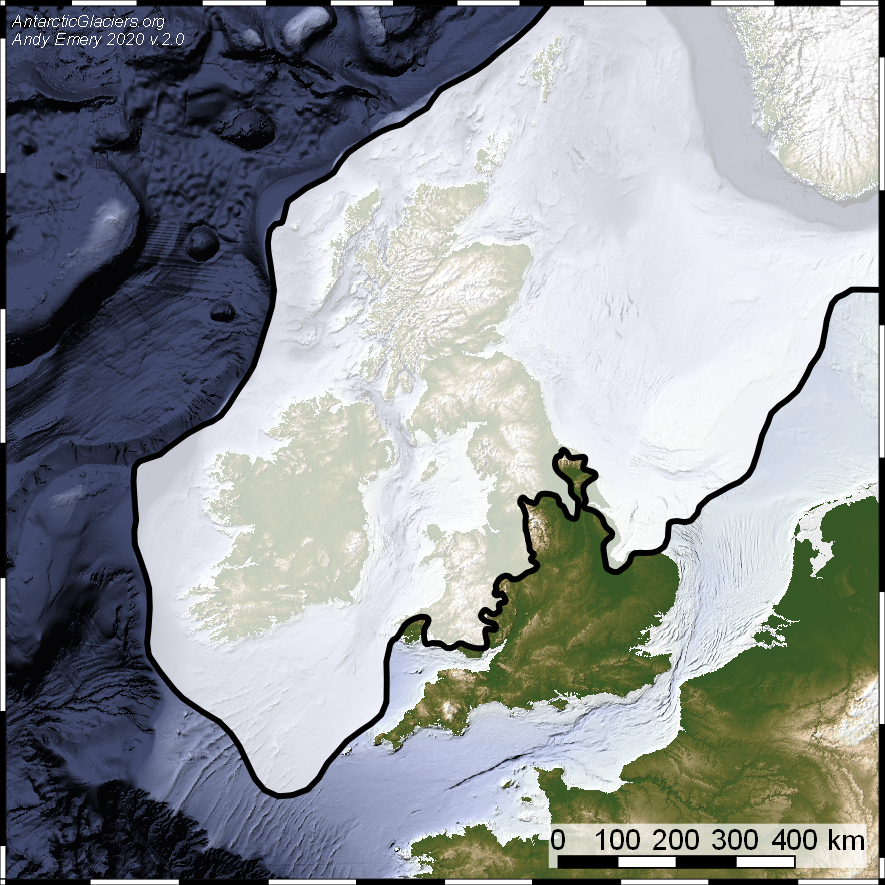

So then, there are three distinct periods of glaciation (that is, the process of glaciers forming and moving) within Britain – the Anglian (roughly 478,000 to 424,000 years before present [BP]), the Wolstonian (300,000 to 130,000 BP), and the Devensian (roughly 27,000 to 11,000 BP). Leaving aside the first two, lets focus on the last – the Devensian (also known as the Last Glacial Maximum), as this one was the only one that would have had anatomically modern humans living through it.

At this point, roughly 2/3 of Britain and Ireland, including all of Scotland and Ireland, most of Wales, and the north of England was covered by what is known as the British Irish Ice Sheet. Starting in the Arctic, as the land cooled this glacier moved further south until it reached a limit at about 27,000 BP, at which point the cllimate began to warm, and it slowly began to retreat, and was gone by 11,000 BP. The effect that this moving back and forth had on the land was catastrophic – carving out valleys (think the glens of Scotland, the Lake District, and even our own Peaks), and forever altering the land.

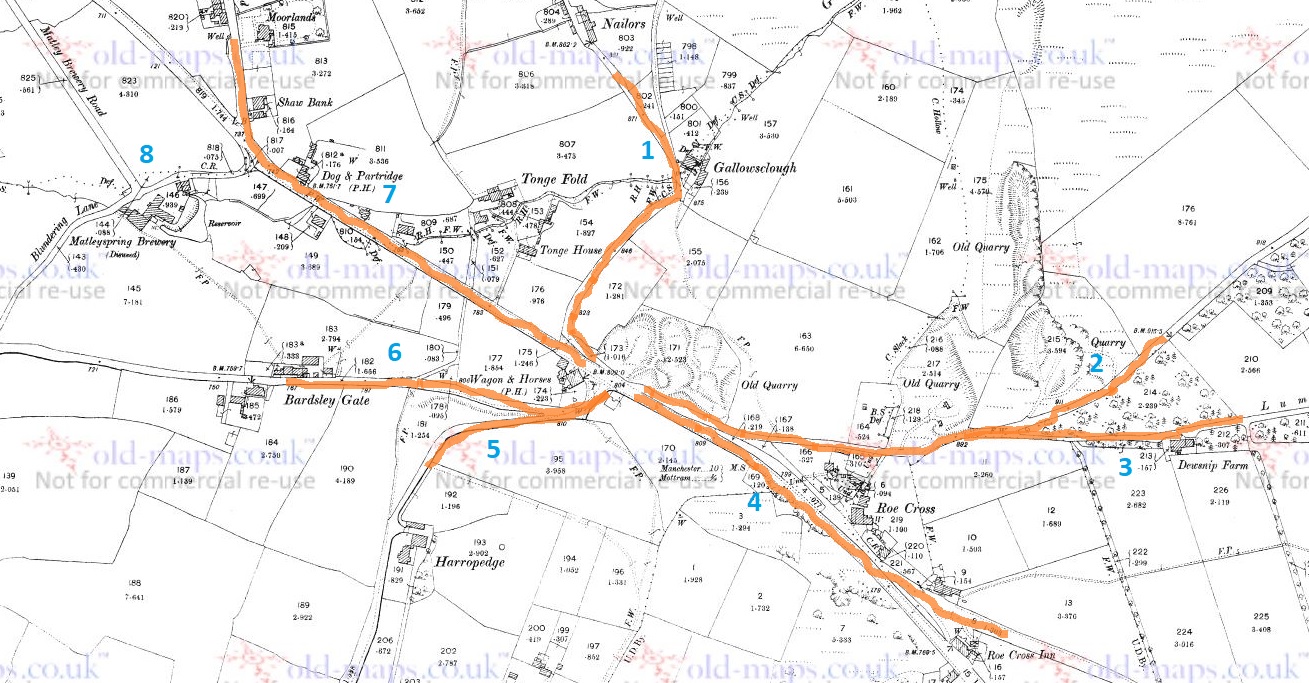

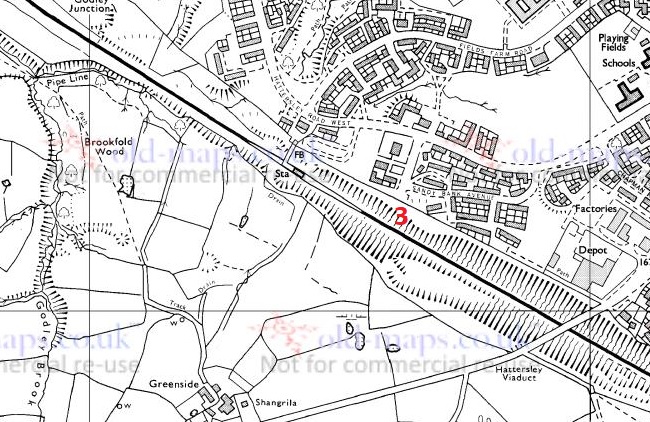

Now, here’s where it gets more interesting… and complicated. There are no definitive models, but it seems that Longdendale was at the southern/south-western edge of the Devensian ice sheet – the literal edge of the glacier in the last ice age. This might explain why the Peak District is, well… ‘peaky’, but the land to the west and south-west isn’t; Longdendale is the last valley before the land smooths out towards Manchester and Cheshire. Indeed, if you look at the above map and think about the landscape to the south and east beyond the edge of the ice sheet, whilst it can certainly be hilly, there are no peaks and steep valleys.

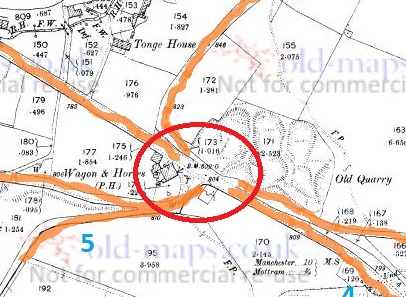

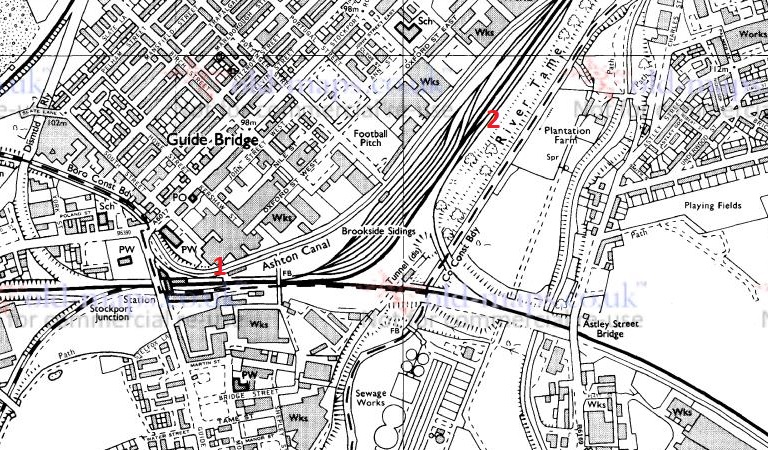

Of course, that’s not to say that the glaciers didn’t affect the land beyond that edge – already frozen solid and all but inhabitable, once the glaciers began to melt, the water had to go somewhere. There is some evidence for what are termed ‘glacial lakes’, huge bodies of meltwater, beneath or adjacent to the glacial edges. There seems to have been one covering the whole of Glossop as it is now – the landscape here being suitably bowl shaped – and which was perhaps dammed at the Mottram end with ice and clay. Not going to lie to you, folks, that honestly makes me feel… weird and terrified. Indeed, originally the Etherow ran to the west of here, toward Manchester, but was forced to change it’s course due to sand, gravel, and ice blocking the original route. And to give an idea of the power that such a lake bursting, one such steam blasted out the gorge (actually, a natural geological fault line) at Broadbottom which the viaduct now has to cross.

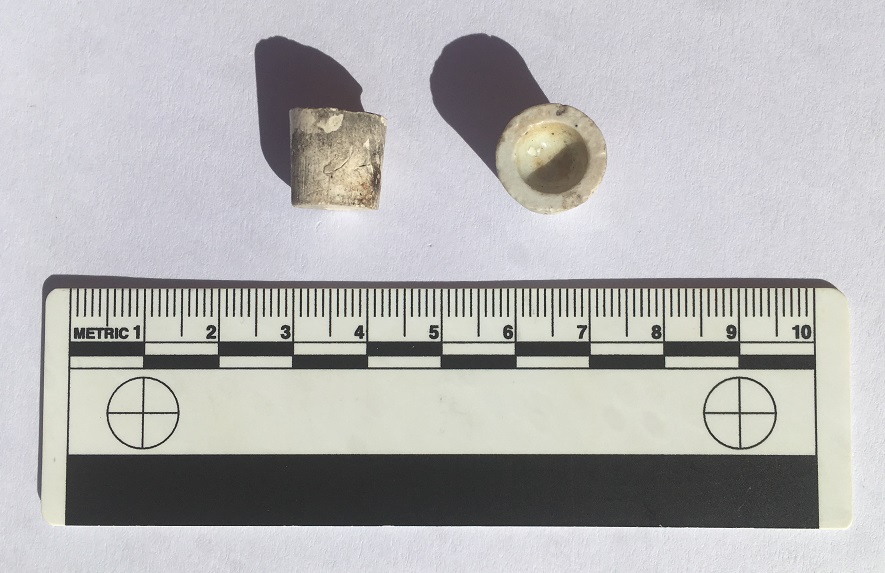

But the glaciers also gave another gift. As they moved up and down (and indeed round – there is evidence that it wasn’t a straight-forward linear motion), they picked up bits of geology – random stones and chipped-off bits of mountain. These they occasionally dropped as they went along in the form of what we know as ‘glacial erratics’ – defined by AntarcticGlaciers as “a far-travelled stone of a different lithology (stone type) to the local bedrock“. Now, the Glossop area has four of these that are known about (but there are a lot of odd looking stones dotted about that to my eyes look like they are erratics, but as I say, not being a geologist, I don’t know). If anyone has a geological speciality, or has any thought about the types of stone these are, and thus perhaps their origin, then please get in contact. The first of these is the one I have already mentioned at Pyegrove, here:

Lurking in the bushes, it hides its history well.

Now, other than it being non-local, and shaped rather like a large pebble (due to the grinding and rolling movement via glacier), I know nothing about it, geologically speaking. It’s coarse, with a sandstone-like structure, but not quite like any local stone I know of.

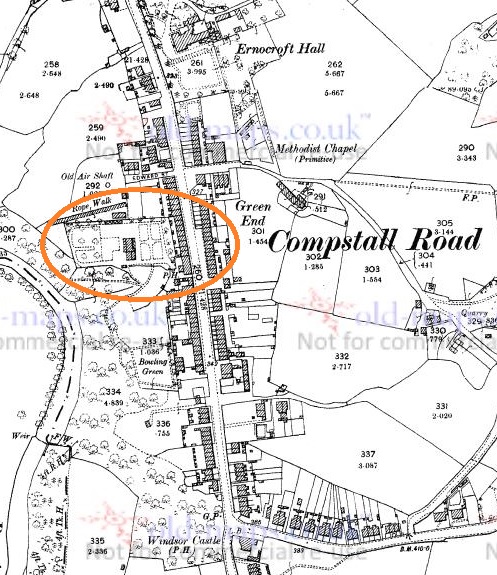

I assume that it comes from geology further north than here, but where? Lake District? Scotland? Norway? Was this where it was dropped? Or has it been found in a field and moved? Possibly the latter, as it is on the field edge, and marks the track between Pyegrove House (and Hurst, etc.) and Glossop, now simply an overgrown hollow path at the edge of the field, but once an important route from Jumble, Hurst and Pyegrove to Glossop.

Of course, it may be that the field boundary used the erratic as a reference point, and thus the track, but I still think it’s likely that it has been moved.

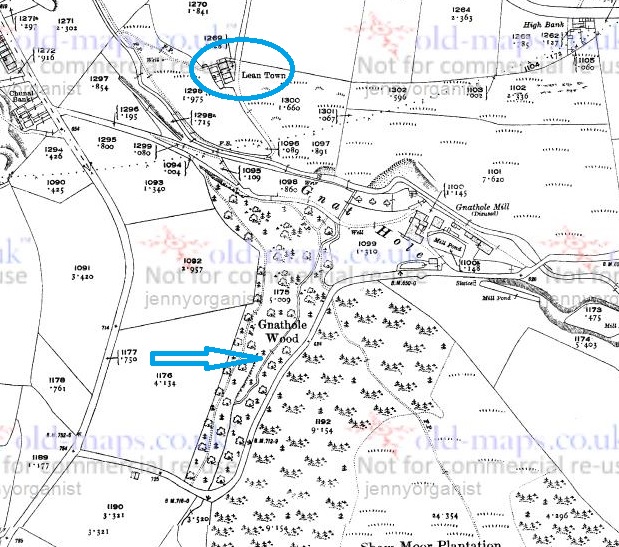

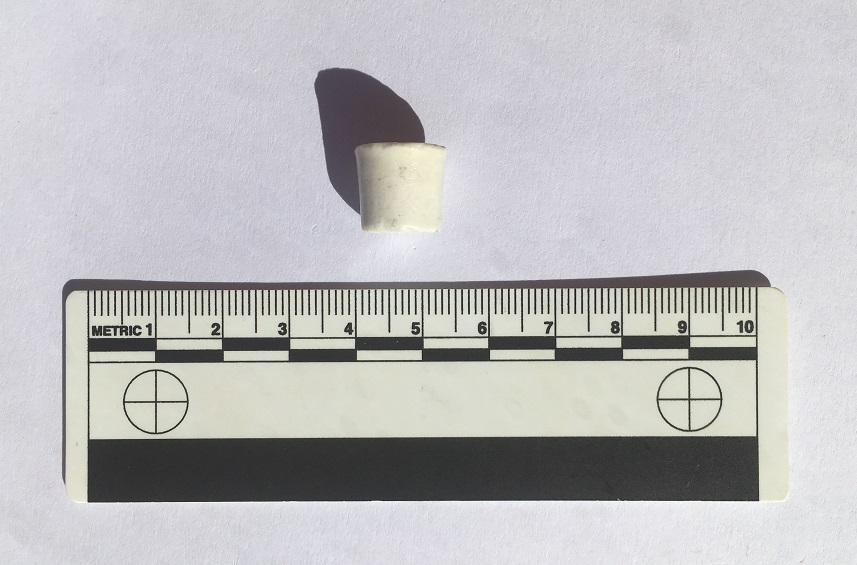

The next erratic is to be found in Howard Park, here to be precise:

So, it’s a very similar stone to the Pyegrove example, possibly even from the same source. Here, in the close-up:

The rock also shows very clearly the marks of being crushed and scraped along other rocks by the glacier.

This one has certainly been moved, but from where?

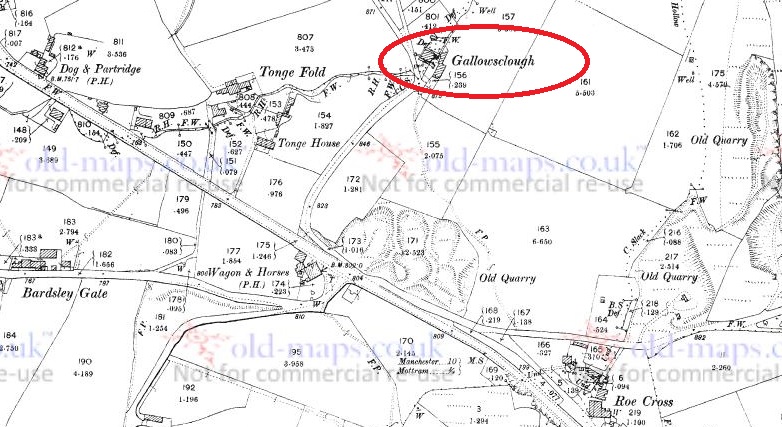

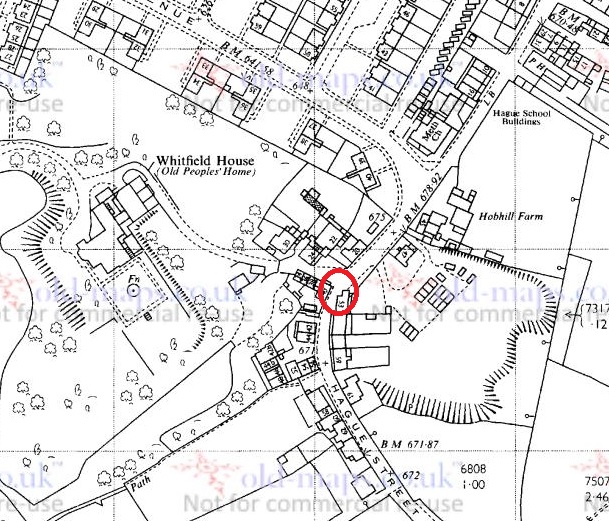

Our last two erratics are to be found in the grounds of the old Grammar School and library building, here, to be precise:

Here it is is close-up:

Here it is in close-up:

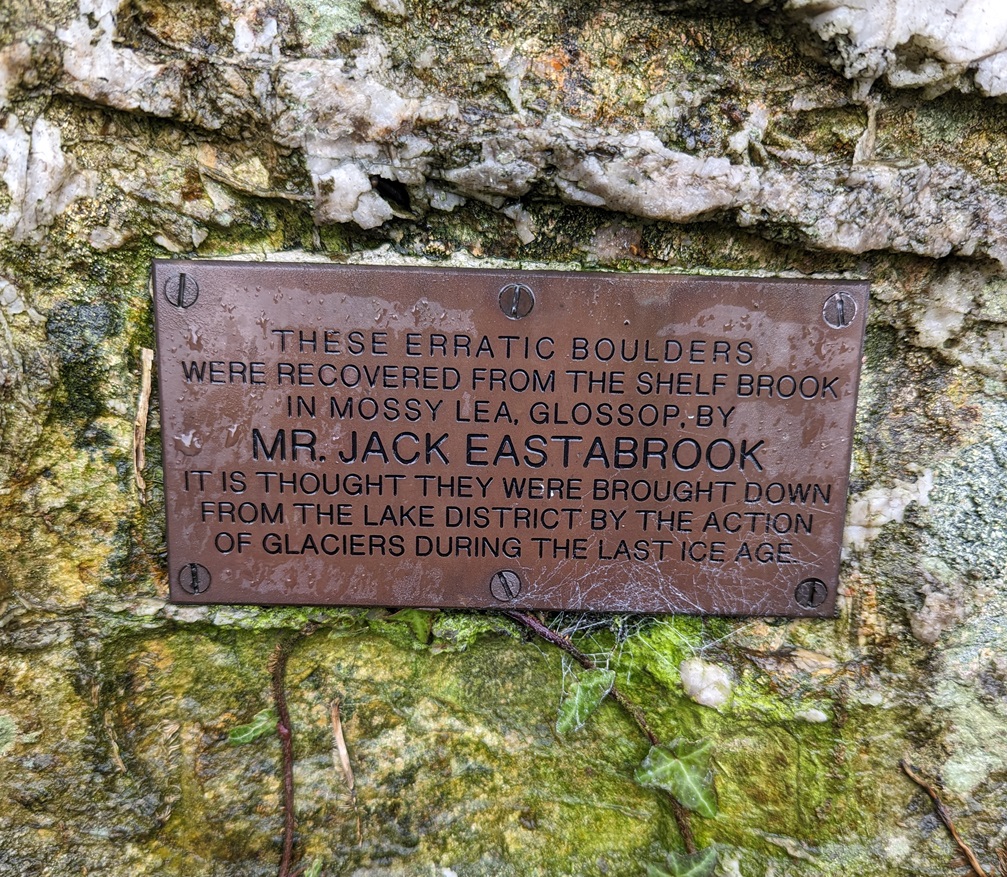

They even have a plaque helpfully explaining where they were found, and potentially where they originated.

As the climate began to warm up, the land began to come back to life – this was the start of the Holocene period, the modern human world. Trees, shrubs, and plants started to grow, and these are soon followed by the animals that eat them. And following them, hunting and gathering, people. By probably 8000BC, at certainly by 7000BC, people were passing through the Glossop area following game in small bands, and moving between seasonal hunting camps. Their movement through the area may have been part of a cycle of many years, and many hundreds of miles from place to place, stopping for a period of months – summer in the higher ground, winter in the warmer valleys – meeting other groups in specific locations, trading resources and marriage partners, and moving on again, through a landscape that was marked only by natural monuments. The Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age, c. 8000 – 4000 BC) is a fascinating period, but we know so little of their daily lives. Indeed our only clues to their existence hereabouts are the flint tools they made and used, and which are quite commonly found in the hills around Glossop.

I’m also going to use this article to put to bed a story I’ve heard from several sources over the years – that Coombes Edge is a caldera – the blown out remains of a long dead Volcano. Essentially, a smallish volcano erupted, and blew out the north-western side, spewing it’s contents over towards Hyde. This is not the case, and the unusual land formation is the result of a huge landslip caused by under soil water movement, and which occurred sometime between 10,000 and 7,000 BP – so somewhere in the Mesolithich period. One wonders if the landslip was noticed by anyone, either as they were nearby, or after they came back into the area and found the huge landslide. And I wonder what they thought of it.

Also, I wonder if we have a look in Shelf Brook, but other streams around here, we might find some more glacial erratics, large and small. Who’s with me?

Right, I’m off to light the fire… and pour a glass of the stuff that warms.

In other news.

There will definitely be a guided archaeological & historical (hysterical?) walk in the next month or so, so watch this and other spaces for news. This will probably be just before the new edition of the Where/When zine – No.2 – comes out. I have decided to aim for 3 zines a year – December, April, and August, but I want to be flexible on this… my life is hectic enough as it is! I’ve also got some ideas for some special editions, but that’s far in the future. In the meantime, who wouldn’t want a Where/When t-shirt with the slogan “What ho, Wanderer!” on it? Just a thought!

As usual, keep in touch, even if it’s just to tell me I’m talking out of my hat. So until next time, look after yourselves and each other, and I remain.

Your humble servant,

TCG