There’s no mistaking some etymologies.

Placenames in the past were given because of what was there, not aspirational or deliberately flowery. They were practical. Descriptive. Truthful. There was no Laurel View if there was no view of laurels. Gnat Hole was not named ironically. And Shittern Clough was… well, you get the picture.

For me, Gallowsclough has always stood out in the map of the area – the clough, or narrow valley, where the gallows were. There is something of the macabre about the name, and I was also aware of a folktale from the area which really made an impression on me (more of that in a bit). So I decided to do some exploring, to see if I could add to the placename, and see if I could work out where the gallows were… as Mrs Hamnett put it “lucky me, you take me to the loveliest places”.

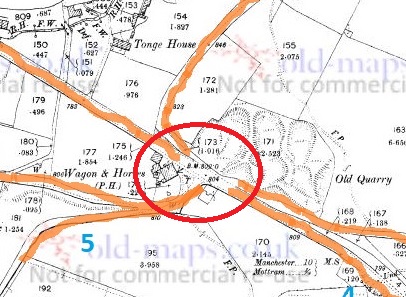

I’ve blogged about this area before (White Stone of Roe Cross), but the area is effectively the Deep Cutting between Mottram and Stalybridge. Gallowsclough is highlighted (the clough itself, or small deep valley, running towards the Dog and Partridge).

So then, the gallows.

The last person to be hanged in public was in 1868, after which time, and until capital punishment was abolished in 1965, executions took place within the prison, away from the public eye. But before 1868 it was a public spectacle, to the point that the hangings at Tyburn were turned into a public holiday. Often associated with the public hangings of the 17th and 18th centuries was the punishment of gibbeting, in which the hanged criminal was enclosed in a tight fitting cage or chains, and effectively left to rot. The body was covered in tar in order to protect it against the elements, and hung there as a warning to others until it finally fell to pieces.

Each area, feudal estate, or manor had a gallows/gibbet, and certainly until the later Tudor period or even the early modern period, capital punishment was the responsibility of the lord or equivalent. It seems that the victims were buried underneath, or nearby, the gallows, but certainly not on consecrated ground. To be executed was to be condemned to eternal restlessness, to never know peace, and to wander the Earth an unhappy spirit.

In order to achieve maximum visual impact, the gallows were normally set up at prominent places – central open spaces, or more normally, crossroads. And so it was here, in Roe Cross. The body swinging, both at execution, and in a gibbet, could be seen easily by both locals, and by travellers moving along the various roads – a physical reminder to obey the laws, or suffer the consequence. Interestingly, this tradition of both execution and burial at a crossroads has given rise to the concept that a crossroads is an odd, supernatural, place. If you want to sell your soul to the devil, where do you do it? Where do you bury witches? Or suicides? Or criminals? At the crossroads, that’s where.

So where were the gallows at Gallowsclough? It is very doubtful that they would have placed them further up the clough – difficult to get to, in arable land, and there are no crossroads. No, I think they erected the gallows at the point Gallowsclough – the clough, or deep valley, upon which the gallows are placed – crosses the road. At almost exactly the point seven – count them – seven tracks join. This is no crossroads… this is a crossroads and a half. Here is a map showing the tracks (numbered).

This is the area close up – you can see the tracks meeting.

The roads are as follows (the numbers are faint in blue in the map above):

- Gallowsclough Road – From Saddleworth, via Millbrook (avoiding Stalybridge). This is the Roman Road between Castleshaw Roman fort and Melandra (thanks Paul B.)

- From… well, the middle of nowhere – local traffic from farms

- From Hollingworth.

- From Mottram via the old road.

- From Hattersley, via Harrop Edge.

- From Newton.

- From Stalybridge, via the old road.

A perfect situation for an execution and gibbet. It was said that it was to these gallows that Ralph de Ashton (1421 – 1486) sent the unfortunate tenant farmers who couldn’t pay the fines for allowing Corn Marigold to grow amongst their crops. The death of the hated Ralph is the origin of the Riding the Black Lad custom and the Black Knight Pageant in Ashton Under Lyne, a tradition sadly no longer undertaken. Naturally, the area is said to be haunted, with the locals avoiding the place, even in daytime. Although, as is so often the case, there are no references, only suggestions.

This is the clough

Of course, whilst I was stomping around, I happened upon a bunch of mole hills…

Evidence of nightsoiling (as I’m sure you all know, having read previous posts about this). The top row right: a medium bone china plate (c.18cm in diameter), hand painted flowers and abstract floral designs in pastel colours. This is quite nice, and is probably early Victorian in date. Middle is a plain white glazed plate, thin, and again about 18cm in base diameter (you can see the ring of the base in the photo), which makes it perhaps 24cm or more in ‘real’ diameter. Left is more difficult – it has an undulating rim, with a curled decorative motif – which means that I can’t tell you how big it is. Over 25cm in diameter, I suspect. It is a shallow dish, or deep plate, and is deocrated with abstract floral designs. Date wise? Late Victorian? Looks more modern than that, though… Edwardian? The bottom four are fairly boring body sherds, though the sherd on the left is a blurred willow pattern, so potentially quite early?

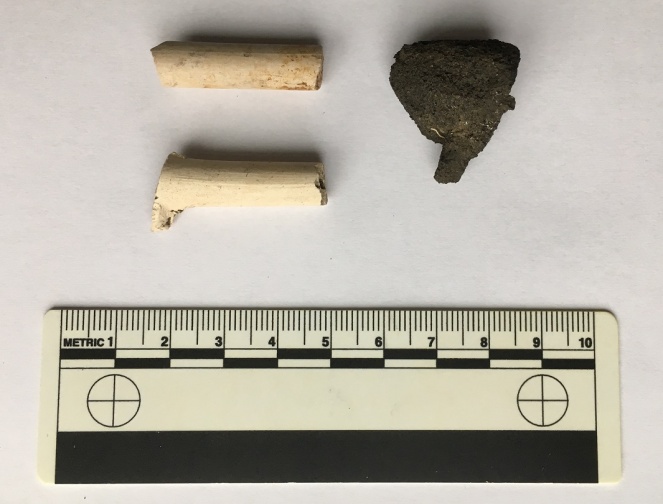

The ubiquitous lump of coal/coke to the right, and the ubiquitous clay pipe to the left. The lower of the pipes is nice as it still has the spur that juts out and forms the base of the bowl, which you can see just emerging. It’s probably early to mid-Victorian in date. -Check out this wonderful website for more information.

And finally, to end on, this lovely thing.

A flake of quartzite that has been struck in prehistory, during the course of making a tool. Flint doesn’t occur naturally in this area, so all sorts of stones were used in the making of stone tools in prehistory. Quartz, though a poor cousin of flint, still keeps enough of an edge to be useful, and this piece carries all of the hallmarks of a bit chipped off a larger tool or weapon – the striking platform (top), and the bulb of percussion (facing, half way down). I suspect that this is Mesolithic in date, so c.6000 – 4000 bc, or thereabouts. I’ll post some more flint/chert/quartzite when I get a chance, as it’s fascinating stuff, and the area is not exactly lacking in it.

*

Interestingly, there is a brewery marked on the map (top left, numbered 8). This is the Matley Spring Brewery, which brewed beer here, using the local spring for water, and presumably selling it in the Dog and Partridge, at the end of the wonderfuly named Blundering Lane. I was going to write a little about it, but came across this site with some information and photographs. Actually, the whole blog is a good read, filled with fascinating titbits relating to the area, so go forth and explore.

*

And finally, as promised, I’ll end with the folk story of Gallowsclough. This is taken from Thomas Middleton’s Legends of Longdendale (the book is a mine of local legends and folktales, as well as some good photographs, and is well worth seeking out – or reading in the pdf format at the link below)

Follow this link for The Legend of Gallow’s Clough.

It’s very Victorian in its telling, but the story is as black and evil as any I have read; there is something about it that disturbs and lingers in the mind – the imagery, and particularly the witch walking away at the end. No, I like a good dark folktale, but this is just on the border of being a little too dark for my tastes. Enjoy at night, and you have been warned…

So there you go. There’s plenty more in the pipeline, so watch this space. As always, comments are very welcome, and all will be published.

And I remain, your humble servant,

RH

This would indeed have been a very busy place – and there might have been yet another route running through it. The two main flows of traffic in the Middle Ages were North-South, from the East Midlands via Mottram and up the (probably) Roman road to Saddleworth and East Lancashire, and West-East from the Manchester area through Newton and Matley to Meadowbank and up Longdendale. This latter line was virtually straight in its original form, leading one writer to think that it might be the Roman road from Manchester to Melandra, but there’s good evidence that that went via Hyde and Pudding Lane in Hattersley; the straightness indicated rather that it had been established at a very early period when travellers were making their way across completely open ground. Only much later was the traffic from Manchester diverted via the growing town of Ashton and the new bridge at Stayley.

However, the North-South route, linking the two main centres of the early factory textile industry, was very difficult for wheeled traffic due to steep slopes at Broadbottom and Charlesworth, and in 1793 two Acts of Parliament authorised the construction of a turnpike from French(es) Top (near Greenfield Station) to the new Chapel-Enterclough turnpike (now the A624 – B6105) at either Brookhouses or Thornsett, near Hayfield. This would have followed the B6175 as far as Copley, then presumably have cut across to the old Manchester-Saltersbrook turnpike, then over Matley Lane near Bardsley Gate and round the west side of Harrop Edge. This would have been a major piece of engineering as only a small part followed existing roads, but it never got further than Copley (with a branch to Stalybridge.)

The reason was probably that in 1803 permission was given for a turnpike from Marple Bridge to (Old) Glossop, the driving force behind which, as with the Chapel-Enterclough road, was the Howard estate, and the most important bits of which were the branches to Woolley Bridge and up Primrose Lane/Turnlee Road to Charlestown. These were designed primarily to open up new sites for mills along the valley bottoms, but they also created a by-pass of Broadbottom and Charlesworth, which whilst less direct than the Copley-Thornsett route would have made it too risky an investment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

After spotting what appears to be the remains of a Roman road agger behind the Rising Moon pub using lidar, the case for Mately Lane being on the course of a Roman road is much stronger than it was. You can read a full report here: http://www.twithr.co.uk/lancs-gm/M711.htm

LikeLike

Many thanks for this, Neil. I am slowly digesting this, as I think it is suggesting all sorts of things to me! Those images are so clear!

LikeLike