Good evening.

(well, it is here and now, but I suppose it depends on when you are reading this… in which case, feel free to substitute “evening” for whatever part of the day you happen to be reading this.)

Perhaps I should start again.

What ho!

A short one today – I realise that I haven’t been as active as I’d like, so rather than labour over a larger post, and as a sort of proof that I’m still alive, I present today’s smaller offering – the area of Glossop known as Bridgefield. This is a place you drive through without ever noticing it is there – blink and you miss it as you go from Charlestown to Dinting along Primrose Lane. It is also a great example of why maps are so useful as a record of places – without it being drawn on the map, it is likely that Bridgefield would have ceased to be remembered as a place at all.

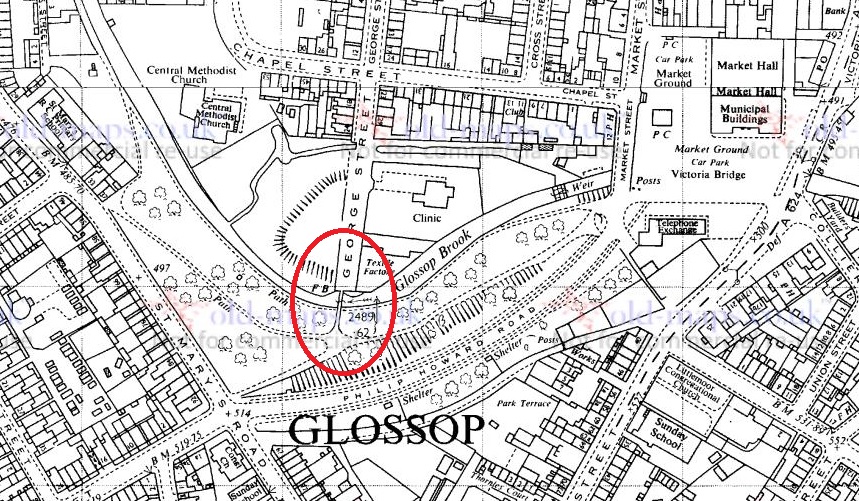

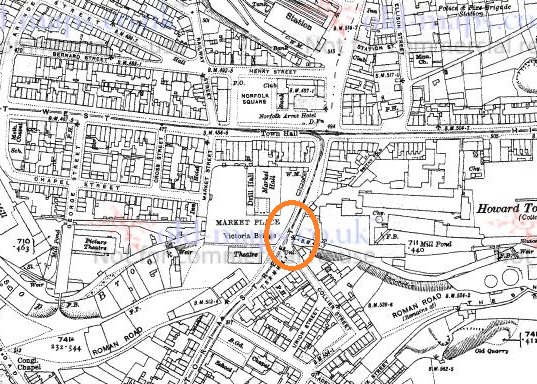

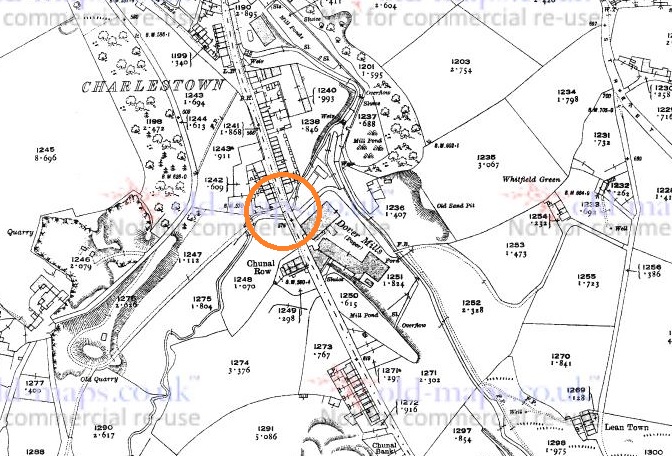

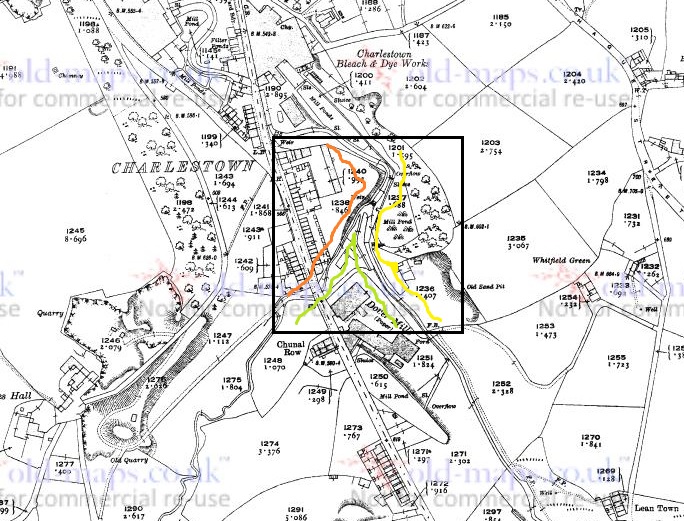

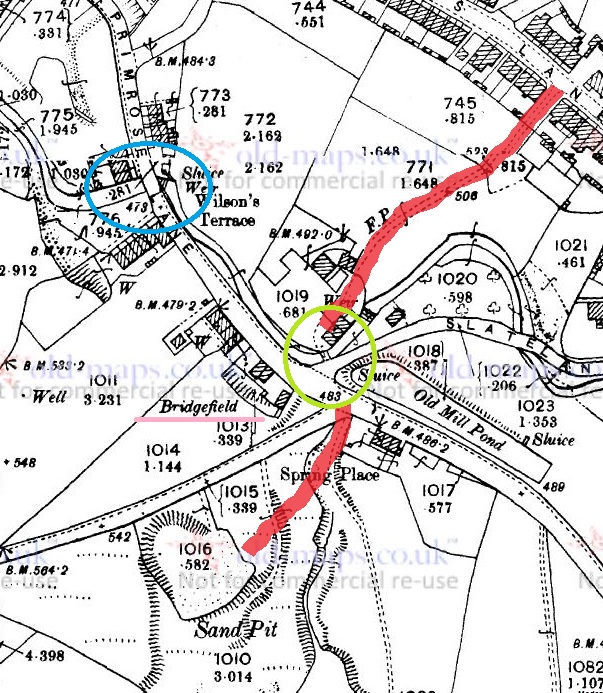

I have commented elsewhere that older names for places are usually based on reality, and reflect a different set of priorities – largely truthfulness in description: Gnat Hole was not named ironically, and so it is with Bridgefield, it was – and is – the field with the bridge. Well, actually bridges, plural – there are two. The first is where Primrose Lane crosses Long Clough Brook, circled in blue on the map below. But it is the second one – a small footbridge over the Long Clough Brook – that I think is the more interesting of the pair, and is indeed the older. Moreover, it actually is in the ‘Bridge Field’, rather than two fields over. And so, this humble little bridge is the target of today’s fevered ramblings. The bridge, or to be precise an earlier incarnation, is circled in green in the map below.

It crosses Long Clough Brook at the bottom of Slatelands Road, and now forms the bottom end of a footpath from Pikes Lane, emerging into Primrose Lane. This track – marked in red in the map above – wends its way between houses and land, and is known locally as the Chicken Run; indeed it still has chickens at the bottom. It was also known as the ‘Giggle Gaggle’, apparently, which recalls strongly the ‘Gibble Gabble’ in Broadbottom – another track that wends its way between houses and land. Indeed, it is suggested that Gibble Gabble (and thus Giggle Gaggle) is a localised (Mottram, Broadbottom, Glossop) dialect name for what is known elsewhere as a ‘ginnel’ (a track that wends its way between houses and land), which makes sense (here is a little more on the subject). According to A Journey Through Glossop by Kate Best and Owen Russell this same trackway was also known as Burneen by the nuns of the convent on Shaw Street, who used it to get to Hobroyd. Burneen is a version of the Irish term, Boreen, which means… anyone? Anyone? That’s right – a track, usually one that wends its way between houses, etc. There is a theme here… if only I could spot it. David Frith in his Pathwise in Glossop and Longdendale (p.60, Path 40) notes that this path went through allotments, and was known as the ‘Flagged Fields’, again strongly suggestive of a maintained trackway or road.

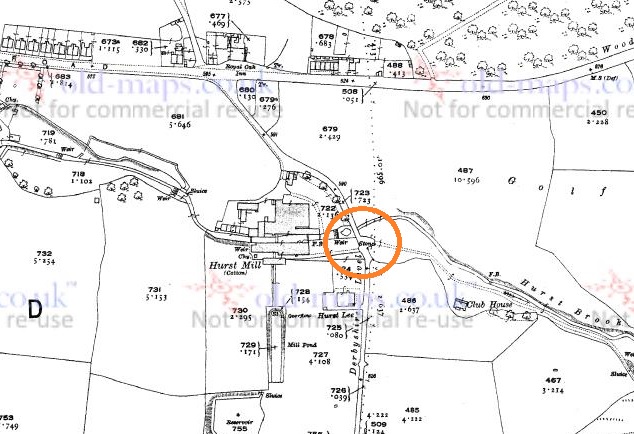

Joking aside this track is very important; I am convinced it forms part of the medieval road (such as it was) between Charlesworth, via Simmondley, to (Old) Glossop. The track goes along Old Lane in Simmondley (the name is a clue), down a sunken trackway that might indicate both age and heavy use, and emerges along another ‘fossilised’ footpath, preserving the original trackway ‘in stone’ – here, at the bottom of Simmondley New Road and Moorside Close:

It continues along the footpath until it meets Pike’s Lane. This track will be the subject of a future blog post as it is a vital part of the history of the area, and well worth an explore, but for now let’s return to the bridge. Here it is, then, the current bridge of Bridgefield.

This bridge is quite modern, being made from rolled steel ‘I Beams‘, and it is clearly the latest in a long line of bridges of various sorts.

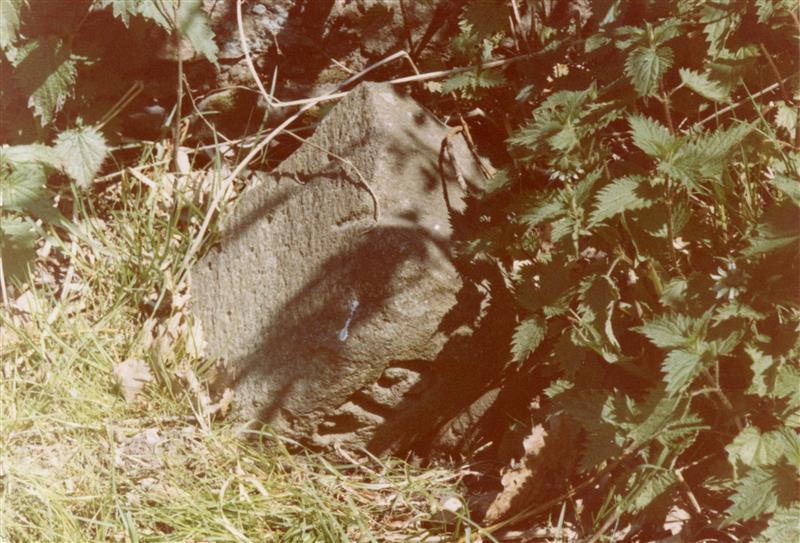

We may assume that the earlier bridges were made from stone in one form or another, but looking into the brook, I noticed some large flat stones – much bigger and more substantial than paving slabs – that look out of place.

Am I wrong to imagine that these once might have made up the medieval and early modern bridge in the form of a Clapper Bridge? The stones having fallen, but not moved very far by man or water.

If I’m honest, I probably am wrong; the whole area has been extensively messed around with by the building of mills and mill ponds, as well as work on the brook itself with the building of weirs and shaping the banks. It’s difficult to get an idea what the area would have looked like, and it’s unlikely that any vestiges of the original bridge remain. But still, let’s imagine.

EDIT

Actually, further evidence to support the Clapper Bridge idea might be suggested by the fact that Slatelands Road, which runs down to the bridge, was once known as ‘Stoney Causey‘, the Stoney Causeway. The word ’causeway’ normally indicates a raised roadway across wet ground, as opposed to a bridge per se. which would fit quite nicely.

However, the importance that was once given to Bridgefield is underlined by the fact that the Reverend John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, preached here. Now, that Wesley preached in Glossop is not in itself big news – he preached all over, favouring the open air, and had a fondness for this part of England, returning time and again to spread the word of his particular brand of Christianity. But the fact that he chose Bridgefield as the location for the crowds of people that would have gathered – some jeering and making mock, others listening intently and converting – is significant. It indicates that this was an important place, and vital in communicating between towns – Glossop and Charlesworth/Simmondley, but also one that was well known enough that people all over Glossop would come and hear him. In his diary, Wesley records the following entry:

Friday, 27th March 1761

“I rode to Bridgefield, in the midst of the Derbyshire mountains, and cried to a large congregation, “If any man thirst, let him come unto me and drink.” And they did indeed drink in the word, as the thirsty earth the showers.”

Well there you go. Who knew that this often overlooked corner of Glossop had an interesting history. As I say, I’m going to blog about the Charlesworth to Glossop track in a future post as it’s a hugely important thing, and part of a larger project that is trying to identify all such trackways in the immediate area. I also recently did some mudlarking in Long Clough Brook, so should probably post the results.

Right, until next time, please take care of yourselves and each other.

I remain, your humble servant.

RH.