What ho you lovely people!

I trust you are all recovering from reading the mighty publishing phenomena that is Where/When Issue 1? Move aside JK Rowling… Harry Potter was good, but was it ‘Pottery’ enough? See what I did there? Pottery… Potter…

What? What do you mean “don’t give up the day job”? This is my day job! And you, sir, are frankly uncouth! Honestly, what do you mean there are “funnier types of fungal infection”?

If you haven’t bought a copy yet, go and grab one from Dark Peak Books, or from me, if you can track me down. Or even download a free copy (link above). A perfect stocking filler, even if I do say so myself. Oh, and plans for a second and third edition continue to form… watch this space. Or Twitter. Or Instagram. Or just get in contact!

Anyway, shameless self-promotion over with let’s get on with the show, so to speak.

So, I recently became aware of a group of wonderful people – The Friends of Whitfield Rec and Green Spaces (their Facebook page is here). They are a group of Whitfield residents who are helping with the day-to-day upkeep and improvement of Whitfield Recreation Ground and other green spaces (for example planters, and other bits of land that might otherwise be neglected). A wonderful idea; we who use it, help keep it usable rather than rely just on the council who, with the best will in the world, don’t always the time and resources, or the local connection, to do this. I’m a big and passionate believer in the phrase “be the change you want to see in the world” (a saying usually attributed to Ghandi), and this group is a great example of this in action.

This summer they planted a pile of… er… plants in the grass around Whitfield Wells, improving the look of the area and adding a little wildness – an excellent example of what they do. And a few weeks ago they organised and installed some good looking new benches at the Rec. giving me somewhere new to sit and ponder the world… and my own navel whilst Master C-G and assorted other Herberts run riot.

The eventual idea is to landscape mounds and hedges around them, creating a wonderful usable social space. But back to the present, and the realisation that one cannot make benches without breaking soil – or something – and my spidey-sense began to tingle… do I smell pottery?

I did indeed.

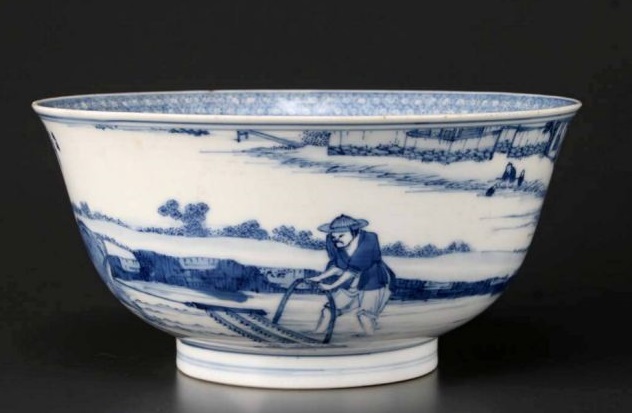

Most of the stuff I found was typical late Victorian and early 20th century tablewares. Not unexpected, and it is largely domestic rubbish, on wasteground, dating from a time when there was no rubbish disposal. Some of the more interesting bits in the above photo, then. Top row, second from right is a shallow bowl or plate with a rim diameter of c.18cm with a hand-painted red band running on the interior – a common motif in early 20th century pottery. Next to that is a fragment of a large rounded jar with a decorated out-turned rim (I should probably start explaining what I mean by all these terms… possibly). And next, a rolled rim from a brown stoneware cooking pot. Bottom row, second from left is a sherd of open pattern spongeware. Fourth from left is a sherd that has decoration hand-painted on the top of the glaze, and the two sherds on the far left are porcelain. As I say, fairly mundane.

However, some pieces were a bit more interesting.

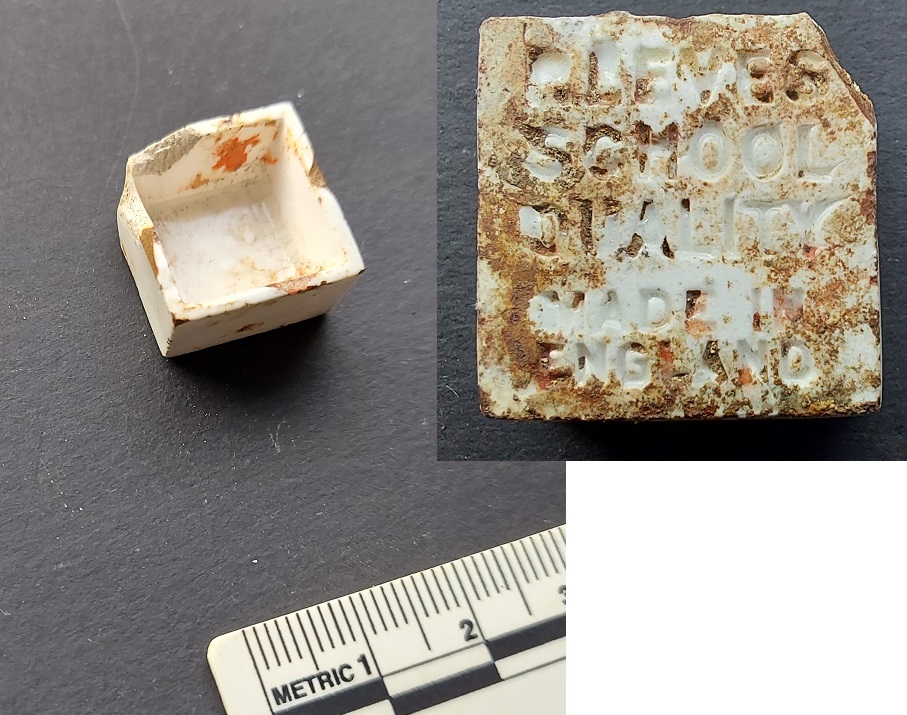

First up, we have a fragment of a Pond’s Cream (or similar skin care product) jar.

It is made from milk glass – an opaque type of coloured glass – and is roughly square shape in plan, with rounded edges and large vertical grooves; it would have looked lovely when whole. It also has a screw top, which generally means it is early 20th century in date.

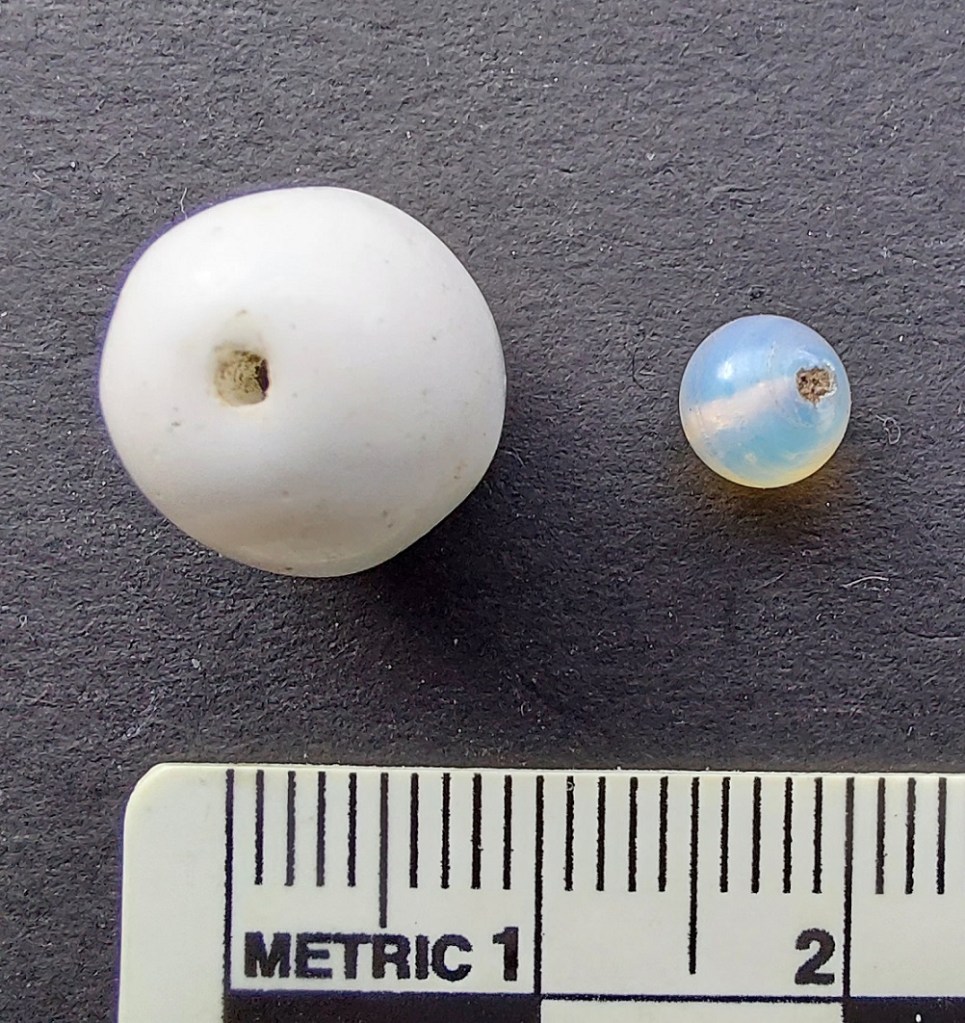

These three are quite nice, too.

Top left, a small plate of Shell Edged Ware, which my own guide suggests is mid Victorian. Bottom left is a hand painted tea cup of c.10cm diameter; it would have been quite lovely. Right is a sherd of Banded or Annular Industrial Slipware, with a rim diameter of c.10cm, and probably from a Late Victorian tankard (they are common in this design), and perhaps, we might speculate, from The Roebuck pub on Whitfield Cross.

Left is a lovely sherd of Spongeware – a flower from a much larger design. Right is the neck from a Brown Stoneware bottle or jar of some sort. The incised decoration on this sherd is very sharp, indicating that it came from something potentially very fine. Both Early Victorian at a guess, so perhaps heirlooms when they were thrown away, or indicating that there is earlier material in the ground below the Rec. – which would be unsurprising.

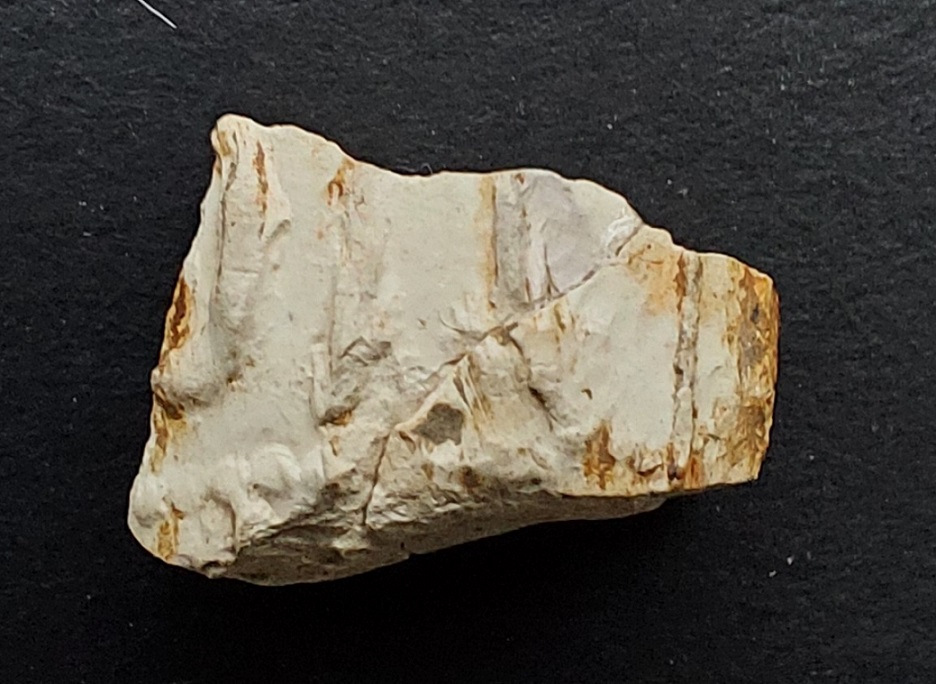

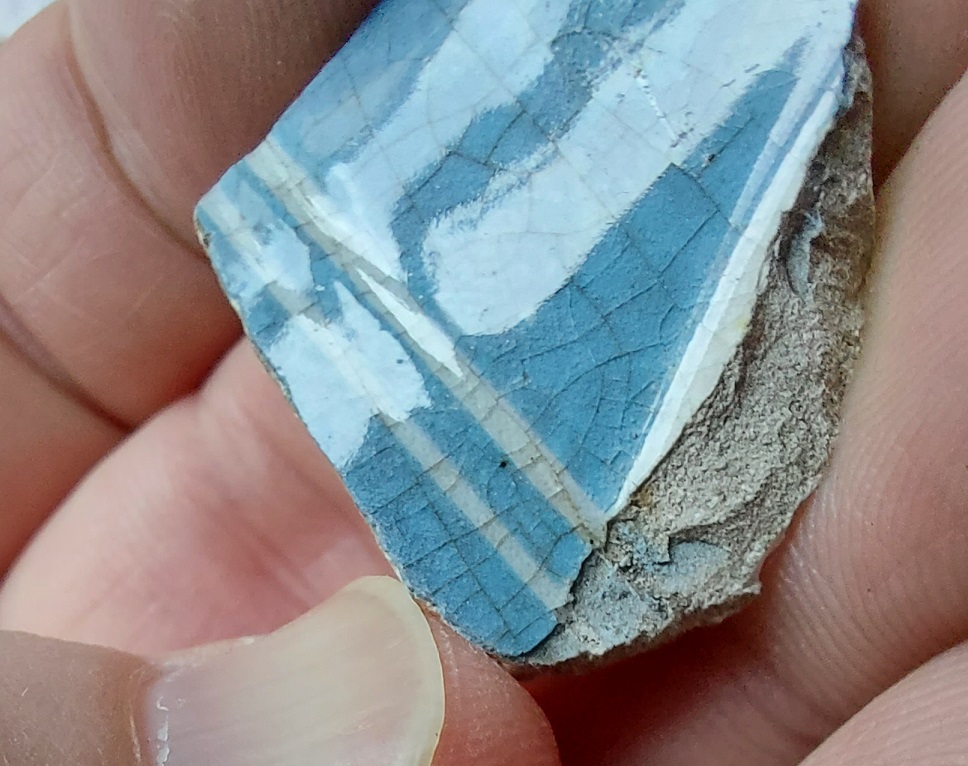

I love this next sherd – a ring foot from a larger open bowl or serving platter.

It looks boring, but is almost certainly early Victorian, and has seen some heavy use, perhaps indicating it too was an heirloom when it was broken and disposed of.

The wear on the ring foot is clearly visible – it has been moved about a lot – in and out of cast-iron ovens in particular – scraping off the glaze and wearing out the ceramic underneath. Also, note the blue tint to the pooled glaze, indicative of a Pearl Ware, and which was largely unused after about 1850. Knowing this sort of thing is the reason I’m a hit at so many parties… such is the burden of the sherd nerd!

Looking at the interior surface you can see many scratches – cut marks made by a knife, probably cutting up meat in the process of serving food. This vessel had seen lots of use before being tossed into what would become the Rec. I love it – the human touch.

Finally, there was this:

It may not look impressive… and to be fair it isn’t. It’s a piece of spent coal – or cinder – and it’s what is left over when you have burnt coal. But it is a hugely significant in that every house would have produced lots of this material, and it should really be seen as a marker of domestic life in the late 19th and early 20th century. I love it for that… not enough to keep it mind, but it is a lovely, if very common, little piece of social history that I wanted to share with you.

So my sincere thanks then to the Friends of Whitfield Rec and Green Spaces for inadvertently sponsoring this month’s post!

Whitfield Recreational Ground has an interesting history – I’m not going to go into it too much as I’m not sure I could do it justice in this article, although it does need doing. Briefly though, Robert Hamnett (the historian) notes that Wood Street – and presumably the whole area – used to be an open field. He states:

“When I first remembered it there was a disused brick yard in the centre, with numerous depressions, which after heavy rain became dangerous to children playing there; in fact there have been cases of children drowning there”.

The whole area was improved and landscaped by George Ollerenshaw in the late 19th and early 20th century. He built the houses on Wood Street, and donated the library building that once stood at the southern end of the park (now the toddler park). His monogrammed initials and date of 1902 are on the Wood Street entrance to the park.

Obviously, over the years I have picked up a few bits and pieces from the Rec:

On the left is a sherd of nice and finely incised Brown Stoneware, probably from a bottle, and possibly early Victorian, as later types are less precise and do away with the incised bits. The middle sherds – one on top of another – are bog-standard Blue and White transfer Printed Ware. The two bits on the right are Salt-Glazed Stoneware, and probably from a ginger beer bottle. Lovely stuff this (and the subject of a future Rough Guide). I also think I can just about make out a smudged fingerprint on the exterior from where the pot was moved whilst the glaze was still wet. Possibly.

Excitingly, we have this:

A clay pipe bowl fragment, with rather lovely fluted decoration – flat panel of gadrooning (don’t say we don’t learn you nuffink on this website… and yes, I didn’t know either, I only learned it accidentally by researching this pipe!). However, nice though it looks, it is roughly made; the seam, where both parts of the mould come together, is coarse and untrimmed, and the clay has been poorly formed in mould. This is mass production in the Victorian period.

And finally, just like the cinder piece above, we have a very mundane but quite important object… a piece of roof slate.

It really is mundane, but is quite informative. Slate is not local: Wales is it’s origin, and until the railways enabled the movement of relatively heavy fragile material like this, that’s where it would have stayed. Once the railways were established (c.1840’s onwards), it quickly became the roof material of choice – just as strong as local stone, but 20 times the weight. indeed, you can usually date the houses of Glossop to roughly pre- and post-1850 by the roof material: stone vs slate. This slate has a flat smooth edge (at the top in the photo) where it has been shaped, but other than that, it is utterly unremarkable, and it simply exists as a remnant of the 1000’s of houses that once stood very close by but which were pulled down during the rebuild of this area during the 1960’s. Indeed, the roof of the public library that stood here was also slate, so it might be part of that as I found it not 10 feet from where it once stood (underneath the toddler play area).

None of these finds have a context – they are all simply rubbish dumped here mostly when it was an open field and before it was transformed into a park. It’s interesting to ponder that for a moment. The Victorians were awful when it came to litter; everywhere they went they left a trail of pottery, glass, metal, and bone – rubbish all over. Now arguably, these are organic, and are not largely made from toxic oil-based plastics as much of our litter is, so not as ‘bad’. Nonetheless, it is safe to say the Victorians were absolute scumbags, and although some of it will have been picked up, there is still lots to be found. If groups like the Friends of Whitfield Rec and Green Spaces have their way and remove all the litter from these places – and I hope that they/we/you achieve this – then are they doing a future me out of a blog post or two? There may be no rubbish to mudlark/fieldlark and blog about! Unfortunately, the massive amount of plastic rubbish that seems to crop up everywhere you look would indicate that this is not the case, and in 200 years no doubt some sad geeky bloke will be publishing a monthly article on a website, and enthusiastically waxing lyrical about this piece of rubbish or that bit of bottle. Imagine…

Get in contact with the Friends via their Facebook page; help them out, give them ideas, give them time, resources… even a cheer. They really do deserve it for everything they are doing, and attempting to do (read a bit more about them and what they do here). Also, do something simple: pick up a piece of rubbish from the street and put it in the bin – every bit we do, helps the bigger picture. And the future me won’t hold it against you, honestly.

That’s all for now, and it only remains for me to wish you a very merry Christmas whatever you end up doing. Personally, I shall be basking in the glow of a fire with family, some cheese and a large glass of the stuff that cheers. So here’s a health to you all, and I hope you enjoy my favourite ‘modern’ Christmas song.

And/or my favourite more traditional song:

I’ll be back in the new year, but until then, and especially at this time of year, please look after yourselves and each other, but until then, merry Christmas (and a merry solstice).

I remain, your humble servant.

TCG