As you walk down Freetown toward St James’s church, just before you get to Charlestown Road there is, on the right-hand side, a small thin passageway that ends in a gate, probably leading to someone’s back garden or something. Now, I’m not sure if this private land as such, but I don’t think so. It is, rather, one of the anomalous bits of land left over after the extensive demolition and remodelling that this part of Whitfield underwent in the late 1960’s. A sort of architectural no-man’s land, the result of imposing a rigid housing plan onto an already existing street system, and one that had grown somewhat organically, and in a ramshackle and piecemeal way throughout the 19th Century. It doesn’t quite fit, so there are these angles and nooks left over which I like to explore. I never can resist a good nook!

This one contains a bit of a surprise. A fireplace. A large inglenook fireplace made up of three stone – two uprights and a lintel – carved, dressed, and sitting proudly in the wall, exactly as it should be.

Except it’s not… it’s outside.

What you see is the front of the fireplace – as you face it, you would have had your back into the room. But there is no room.

Now, putting my anthropologist head on for a moment (as we archaeologists do fairly often), we may note that humans almost universally, and throughout all periods of history, have placed great importance between the ‘outside’ and ‘inside’. This binary concept is prevalent throughout our lives, and is just about hard-wired into our brains. The inside of a house represents the safety of the domestic and the social, the known familar world, one with distinct limits (the walls), and one that is warm and safe and light. The exterior is the opposite of that – it is dark, wild, cold, dangerous, full of unknowns and without limits. Out there, we are helpless, alone, and out there, man is no longer the hunter, but is the hunted, pursued by predators. Consider too the garden; technically outside, it can be seen as symbolically taming the wild. It is outside, but is not – it is bounded by walls and fences, and the grass is cut, unwanted plants are weeded out, the trees are nurtured and the flowers are fed and watered – it is controlled by us, and is carefully and jealously guarded against incursion from the wild.

Arguably, the whole of humanity’s struggles and the evolution of society is based around this concept – making the distinction between outside and inside, developing the domestic, and keeping the ‘other’ at bay. Certainly the ‘Neolithic Revolution’ is as much about this as it is about farming, and the two go hand in hand.

Now what, I hear you cry, has this got to do with a fireplace? Well, the fireplace or hearth is the embodiment of the domestic, the heart and soul of a house. Warmth, light, food, and safety all come from this one point, and it physically and metaphorically represents the concept described above; beyond the light of the fire is darkness, and we don’t know what lies in the darkness. To see it outside, the exact opposite of where it should be, is, anthropologically speaking, wrong – it is an inversion of the norm, it is unsettling and disturbing, and it is somehow dangerous.

Taking off my anthropological head, it is also a very nice piece of carved stone, and so it’s a shame to see it wasted like this. Indeed, I have a fireplace exactly like this one in my own house.

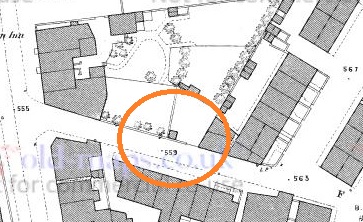

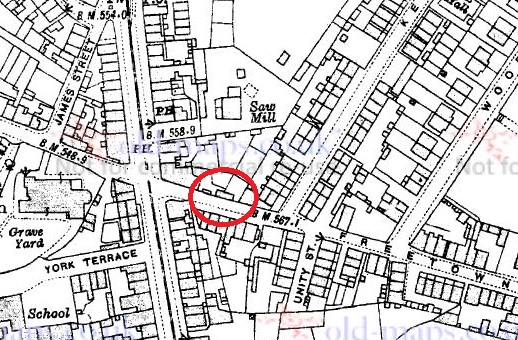

So, how did it end up here? Taking a look at various historical maps, there are a number of buildings marked here over time. The earliest, 1880, seems to have been a small outhouse, possibly a privy. The others are a bit more substantial, particularly that shown on the 1898 map, which may well be our source.

The remodelling, probably largely uneccesary, of Whitfield has thrown up some interesting anomalies (not to mention the re-use of some of the original housing stone – see photos), but I think this is the oddest.

As always, comments and corrections are very welcome.