What ho, lovely people of the blog world. I hope you are all well as we hurtle headlong into summer, each of us fearing what terrible weather will mar an otherwise splendid season. Nevermind, this too shall pass and all that, and indeed we must grasp the nettle by the horns, or something, and make H whilst the S shines…

Today’s post is one of those brought about by happy coincidence, where a series of events conspire, almost waving at you, until you finally notice and say, loudly, “what ho… a blog post!” Or, in this case, a Gate Post. The first event was posting a few photographs on Twitter and Instagram (@roberthamnett on Twitter, and @timcampbellgreen on Instagram, for those of you who might fancy checking it out). Turns out I’m not the only one who likes a good gatepost or two. And then the next event was my seeing a tiny piece of metal in the soil whilst doing a recce for a Where/When (No.7, to be precise… Of Forts and Crosses: A Mellor Wander). All will become clear, honestly.

For years now I have been obsessed with gateposts. Mundane, utilitarian, and always overlooked, a good gatepost can be as interesting as a prehistoric standing stone to me, and truthfully, there is often very little difference: both made of stone, both standing upright, both important in the past, and also in the present. And if anything, gateposts have more interesting features! I mean, obviously prehistoric is fascinating, but they don’t really give us much to go on, whereas the later gateposts… well, read on.

They can be decorated – often just roughly dressed.

But sometimes some thought has gone into them, to create a pleasant design – which for a utilitarian functional object seemingly goes beyond what is needed.

I mean, the only time you see the gateposts is when you are opening a gate to let sheep or cattle in and out, and it’s probably not something you’d see everyday. And even if you did, it’s only for a moment or two, it frankly doesn’t matter if it looks good, and I doubt farmers are wandering around making snarky comments about the plain decoration of another farmer’s gateposts. So why? What is the purpose behind them? I don’t mean they had some sort of secret meaning behind the decoration, rather they simply represent someone’s choices, but why those choices I wonder? Possibly it’s probably more to do with pride in the work taken by the stonemason who shaped it, perhaps a form of identifier: we know it’s person X who shaped it, as he always decorated it with a cross. But then there are those that go beyond simple decoration, and instead turn it into a work of art.

Other times, we find words and dates on gateposts. Often these are faded and barely legible, the weather and environment are not kind to these solid sentinels, and they have no shelter.

The Ordnance Survey often use them to carry benchmarks – after all they’re not likely to be moved, and so are a safe and permanent marker for heights above sea level.

The fixtures and fittings of gateposts always fascinate me, too. Cast iron hoops and hooks, held in place by the tell tale grey/blue of lead. Sometimes you can only see the lead, the actual latch or pintle missing, it’s function no longer having purpose – it is just now a standing stone.

It was actually one of the lead fixings that I found that partly inspired this post. I saw what was obviously lead sticking out of the ground, and bending to remove it as I always do – it’s really not good for the environment – I realised it was bigger than I expected. I studied it for a moment trying to work out what it was, when suddenly: “aha” I thought “that’s a fixing“.

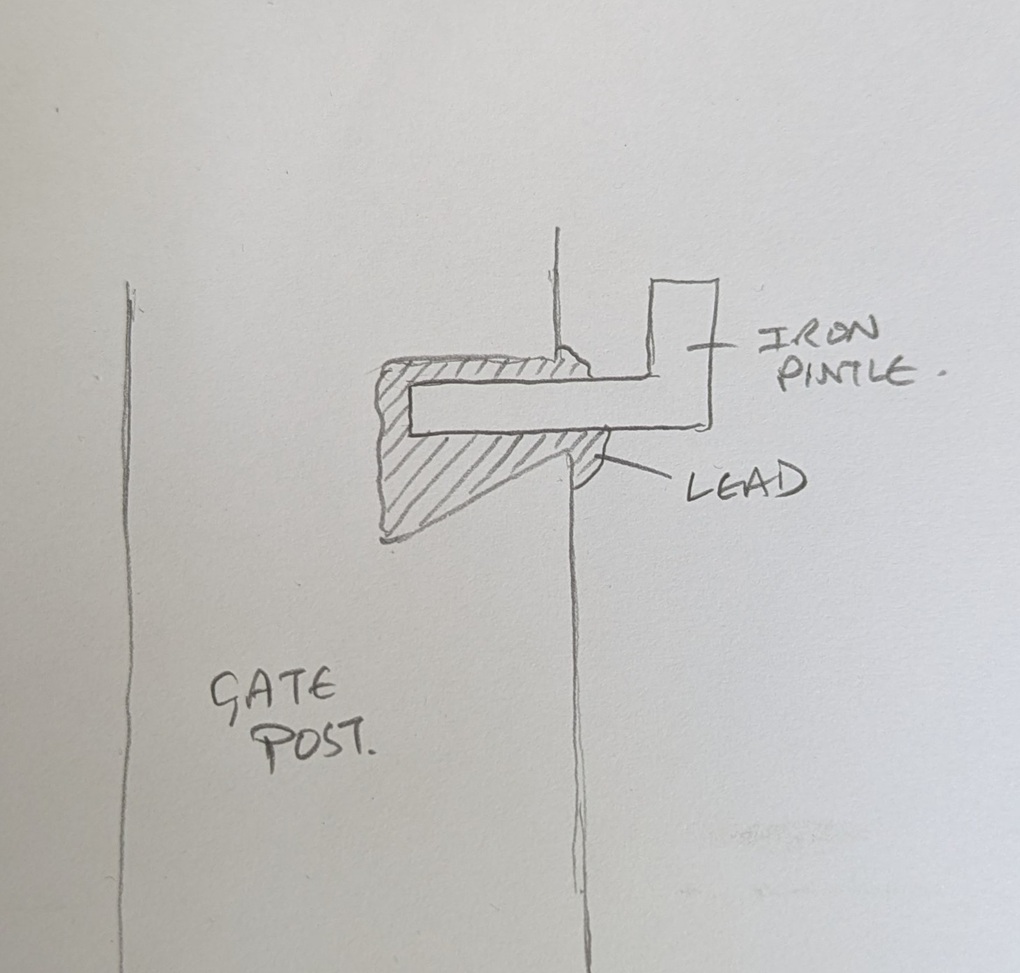

Looking at this lump, and using a small diagram, you can see what it is and how it worked. The long hollow through the middle once held the iron fixture – a pintle or latch, perhaps.

The shape of the lead piece is also a clue to how it actually held this in place. A hole is made into the side of the gatepost that needs the ironwork on it, with the lower part of the hole made deeper. The ironwork is placed in the hole, and the molten lead poured in using a funnel to hold it within the stone and around the iron whilst it cools.

When hardened, it forms a plug that is very difficult to move, keeping the iron work in place; clever, and elegantly simple. It’s also nice to see the ‘inside’ of the gatepost, or rather a cast of the inside, and one wonders why the lead has come away so intact from its original home – one can only imagine that the post itself was broken, freeing this fixing, which then found itself at my feet in the wilds of Derbyshire years later.

In terms of dates for these gateposts – well, it’s not clear. I think the more uniform stones, with a rounded head, are Georgian and Victorian – later 18th and 19th century. However, there are some that I think are significantly older – 17th, 16th, even 15th century, possibly. These are generally less formally worked, are shorter, and importantly are characterised by having a single straight hole through the stone a few feet above the ground.

I was, until fairly recently, convinced that these were marker stones for trackways, the square hole perhaps taking a wooden pointer. However, I started to notice that this didn’t always fit the pattern, and despite multiple blog articles, twitter posts, and it even published in Where/When, I began to doubt this explanation. I then received an email that pretty much confirmed it for me (thank you PB, you amazing man!). In it, the author quoted a John Farey, whose 1815 book – General View of the Agriculture and Minerals of Derbyshire: With Observations on the Means of Their Improvement. Drawn Up for the Consideration of the Board of Agrigulture [sic] and Internal Improvement – gave the following quote:

Anciently, the Gates in the Peak Hundreds were formed and hung without any iron-work, even nails, as I have been told; and some yet remain in Birchover and other places, where no iron-work is used in the hanging: a large mortise-hole is made thro’ the hanging-post, perpendicular to the plane of the Gate, at about four feet and a half high, into which a stout piece of wood is firmly wedged, and projects about twelve inches before the Post; and in this piece of wood, two augur holes are made, to receive the two ends of a tough piece of green Ash or Sallow, which loosely embraces the top of the head of the Gate (formed to a round), in the bow so formed : the bottom of the head of the Gate is formed to a blunt point, which works in a hole made in a stone, set fast in the ground, close to the face of the Post. It is easy to see, by the mortise-holes in all old Gate-Stoops, that this mode of hanging Gates was once general.

Of course, it made sense, despite me banging on about them being marker stones. So, please accept my apologies for this; I am not always correct, and my knowledge is always growing. And thank you PB, who brought this to my attention – this is your discovery, not mine (you can read the book here – P.92 is the quote. There are about 20 of these gatepost types I know of, with many more awaiting discovery. And I actually think these are quite significant, as if we plot their location on a map, we might get a better grip on land use in the pre-industrial period. Marvellous.

I am obsessed with gateposts, and I want you to be, too. Everytime I pass one, I check it out, and often I am rewarded with some nugget of information, graffiti, decoration, or just a blast of the past. Let me know what you find via the contact page, and let’s keep an eye out for those holed ancient stones.

Right, I think that’s all for this month, and lucky you the next post will, I suspect, be a pottery post! Woohoo! I have found lots of cool stuff recently, and it all needs writing about. As always, I have about 30 projects ongoing, not all of which is coming to fruition anytime soon, but some will emerge relatively rapidly – watch this space. In the meantime, do please check out the Etsy store, or the Ko-Fi page – and feel free to buy me a beer coffee, or yourself a copy of Where/When, or even a t-shirt!

But until next time, please do look after yourselves and each other. I know I always say that, but you all matter, and we all need to take better care of each other… the world can be scary place at times, so lets band together and help each other.

And as always, I remain.

Your humble servant,

TCG