What ho, you wonderful – and slightly odd – folk who are reading this. You are here either because you have an interest in Glossop/Pottery/Old Things/The Ramblings of a Sherd-Nerd… or you’re lost. Either way, you might need some help. And either way, pour yourself a glass of the stuff that cheers, sit back and relax.

So then, we have a mixed bag today – some updates and some new stuff, and first up we have placenames.

WHITFIELD: THE PLACENAME

I originally published this post listing all the places in the Glossop area with their first appearance. Whitfield first appears in the Domesday Book of 1086 under the name Witfelt, which is normally understood to mean “White Field”, meaning an open (figuratively ‘white’) land or field, presumably to differentiate it from the surrounding moorland. However, I recently read an interesting article in Nomina: the journal of the Society for Name Studies in Britain and Ireland… as one does. The article is titled “Onomastic Uses of the Term “White“” by Carole Hough (read it here). Briefly, it suggests that amongst all the other possible meanings for the word ‘hwit‘ (White), one that is often overlooked is that relating to dairy foods and milk – literally ‘White Meat‘ – for which there is a lot of evidence, particularly when used in conjunction with a farm or land place name element. If we consider this in relation to Whitfield, we might understand it as the field where diary produce is made, and hence the Cheese Town of the title. We can’t say for certain, but it’s certainly a possibility that should be considered, for as we know cheesemaking was taking place here in the 18th century and earlier… so why not? Whitfield, land of cheese! Marvellous!

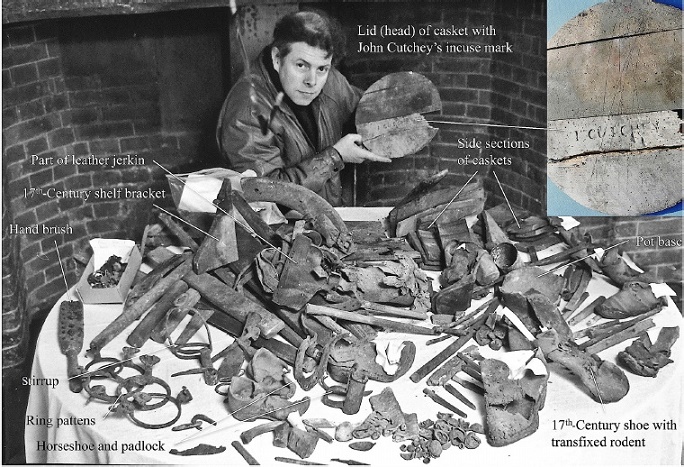

MASONS MARKS ON LONGDENDALE TRAIL

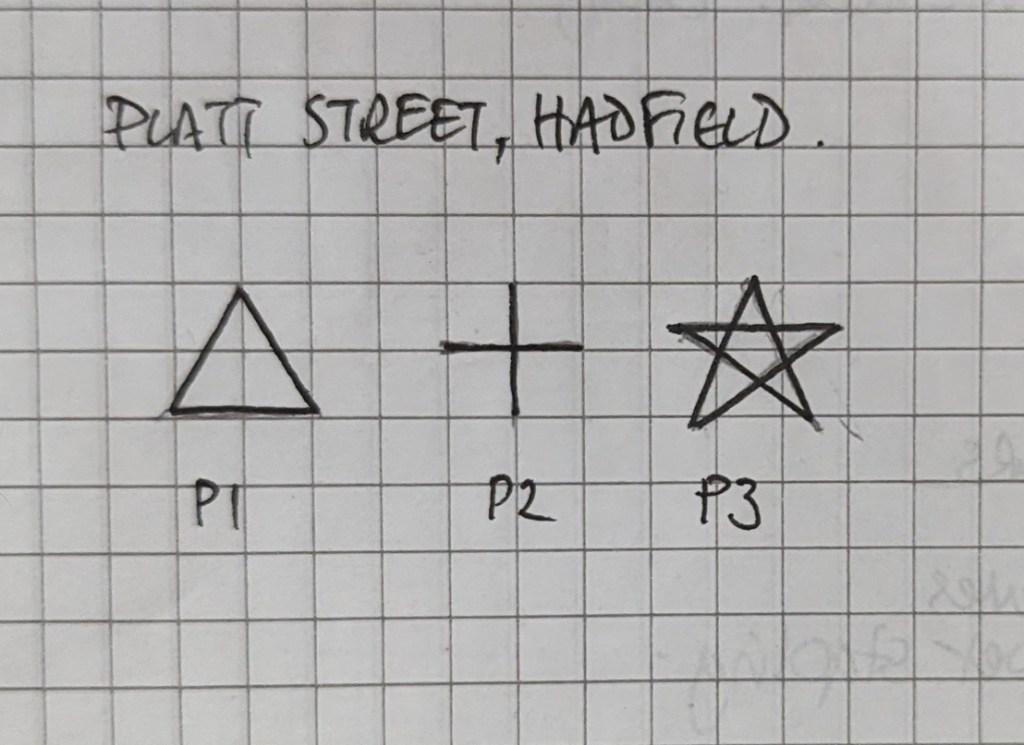

Back when I was a younger man (April 24th 2018, according to my records… 6 1/2 years ago!) I published an article on Mason’s Marks and Apotropaia on the stone infrastructure on the Longdendale Trail (read it here). Master CG was only just 2 years old then… and a lot can change in 6 1/2 years! Having recently got into riding his bike (!), off we went to the Longdendale Trail, giving me the opportunity to look for more marks… and Lo!

Here are the marks so far identified, to add to the corpus of mason’s marks along the line. The first are from Platt Street, the road bridge at the very start of the Longdendale Trail (What3Words is fortified.bracing.wage).

The second lot are from under a bridge that carries an apparently unnamed road leading from Padfield Main Road to Valehouse Farm (What3Words is leader.operated.courts).

As you can see, some of these marks show up elsewhere on the track, suggesting that the same workers were shaping stone all the way from Broadbottom to Woodhead, which makes sense. Truly though, I need to survey the line properly, collecting the forms and locations, etc. I know I’ve said it before, but I honestly think a wonderful project could be made from these marks; recording and comparing them all along the line, researching who they might belong to, raising the profile of the men who physically built the line (not just those who financed it), as well as approaching it from an arts perspective. There’s lots to pick away at here, in fact… if anyone fancies joining me (or indeed, if anyone fancies funding/sponsoring me).

MYSTERY STONES ON THE GLOSSOP – MANCHESTER LINE

Talking of stones, a few years ago I published an article that looked at some odd stones I had noticed during the commute between Glossop and Manchester. Please read the article for more in-depth information, but essentially, 2 pairs of stones and a single example, all exactly the same shape and design, and all with the same single letter designs – ‘I’ and ‘G’. One pair on the platform at Guide Bridge station, and the single example just beyond the station, against a wall, and both of which I had photographs. And another pair just before one pulls into Hattersley station (coming from Glossop, on the right), which was in a ‘blink and you miss it’ position, and consequently of which I had no photograph.

And there the matter lay until the other day! Heading into Manchester, I noticed we seemed to be slowing down earlier than usual on the approach to Hattersley station, and having my phone in my hand, I tried to get a shot of the stones… and succeeded. Well, sort of… in a cruel twist of fate, young Master CG decided it would be an ‘hilarious’ jape to put sellotape over the cameral lens, and as a consequence the photograph looks like it was taken using a potato. Still, the jokes on him… I subsequently enrolled him in a special after-school long-distance running and extreme maths challenge club. That’ll teach him to mess with old TCG! Anyway, here’s the photograph:

So now we have photographic evidence of all of these mystery stones, which is great… but we still don’t know what they are! So, please, if anyone can suggest a meaning or purpose behind these “monogrammed mushrooms” as I have named them (patent pending), then in the name of great Jove, please let me know.

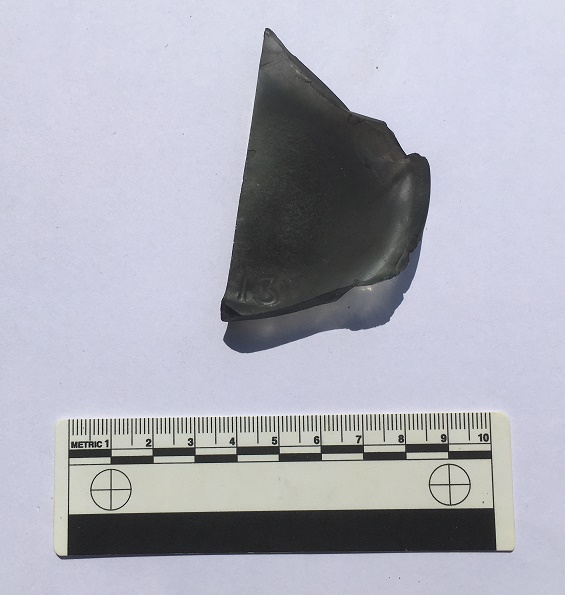

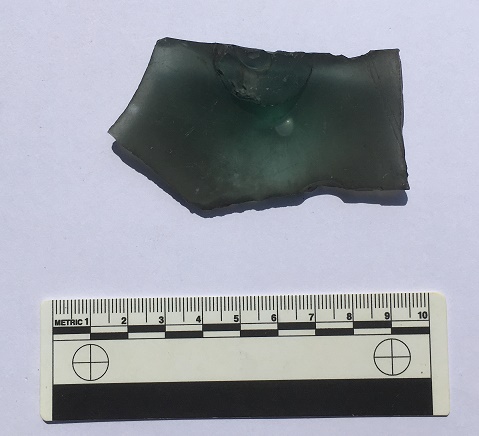

OOOOH… FLINT!

More stone… this a little older, though. Over the course of a number of years, I have picked up a few odds and ends of prehistoric flint from the Glossop area. The hills all around are full of these tiny fragments of a distant past – largely Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age, roughly 8000 – 4000 BC), with some that might be Bronze Age (roughly 2500 – 750 BC). But these three examples I have found much closer to Glossop itself, and always quite by accident. It is worth remembering that Glossop, the Peak District, and indeed most of the North West is not a flint area, and any flint found hereabouts has arrived either by glacial action, or it has been brought here by a human; so any flint you see pick it up! Honestly, flint and chert (a local, poorer quality, flint-like quartz) are both very distinctive against the local gritstone, and once you get your eye in, they stand out from some distance. I’m not a stone man, and whilst I can usually recognise flint that has been shaped deliberately, the finer points of dating I leave to people who know what they’re talking about. Here are the bits I have found:

This first came from a path just below Shire Hill, so might be Bronze Age.

The next flake came from where the allotments are now at Dinting, sitting on a mole hill.

Whilst we know people were here in prehistory, its always nice to see the things they used in their everyday lives. I actually need to report these to the Find Liaison Officer (FLO) as this is prehistoric, and any information from this period, no matter how small, can potentially change our whole understanding of the history of the area. The FLO is the person to report anything interesting and potentially important you find (feel free to tell me as well, but honestly they are more important) – very helpful and genuinely the font of much knowledge.

POTTERY: SOME BITS AND PIECES

Never missing an opportunity to spread a little ceramic-based joy, I present to you a small selection of recently found pottery. Following my own newly introduced rules, I am only taking sherds that interest me, or which are good examples of the ware type. This means that there is more left for you wonderful folk to find, and more space in chez CG… much to the relief of Mrs CG.

First up, two very similar sherds.

Left is from High Lea Park in New Mills, and is the base to a mug or tankard some 8cm in diameter. The right was found on the track below Lean Town, and is the same in shape and dimension, although this is from the body somewhere, not the base. I got very excited both times I found these – they look like Scratch Blue stoneware, which would be very exciting. Alas, on closer inspection it’s clearly earthernware, and thus less exciting. Having said that, they are both from Industrial Slipware vessels, and both early 19th century in date – which is a bit rarer than the usual Late Victorian – and come from something like this:

Sometimes, coming back from school with Master CG, we like to shake up what is in essence a somewhat linear journey from A to B by taking different routes; exploring, Wandering, and just seeing what we encounter along the way; blackberries, elastic bands, the occasional copper nail, a penny, holes in the ground to peer into, and if we are lucky a skip. There’s always something in either of those two latter.

This was from a skip on Hadfield Place. Always, and I mean ALWAYS, look in a skip that has soil piled in it: Glossop’s history almost guarantees that there will be at least some Victorian sherds in that soil. Here we have a rim sherd from a late Victorian/early 20th century marmalade pot – something like this:

The groove running around the pot, just below the rim, is to enable a piece of string to be tied around to keep the cloth lid in place… very characteristic.

Skips and holes… always have a look in both. This next sherd was from a utilities pipe trench on St Mary’s Road:

A lovely sherd of Industrial Slipware, again, this time of a Banded or Annular Ware type. It looks very modern as it is still made, particularly as Cornishware, but it is genuinely early to mid-Victorian in date, and probably from a large bowl or jug. Looking and feeling it again again, I think jug.

This last sherd is another Industrial Slipware – a tiny fragment of Variegated Ware, this one being in the ‘earthworm’ design:

Probably from a jug or bowl, similar to the one in the above article, and dates to about 1800-1820. Interestingly, this one was found in a quarry that was used during the construction of Bottoms Reservoir, and was later used as a tip. Bottoms Reservoir was opened in 1877, and thus the tip can only have been used from, say, 1880 onwards, and actually, judging from what is found there, I think perhaps from 1900 onwards. This means that this sherd – and the pot it came from – was as much as 100 years old when it was broken and thrown away. This makes sense – I still have my great grandmother’s 1920’s salt-glazed stoneware pie dish (I use it to make a really nice tomato and white bean bake with a feta topping, if anyone fancies…) – and is a cautionary tale about using pottery to precisely date certain contexts. People in the past also had heirlooms, and all objects have a biography.

AND FINALLY… WHERE/WHEN 3

Well, Where/When no.3 is now on sale… and selling well. You good folk seem to like a walk, some history, and a pint… who knew? Well, I think we all did to be honest. You can get it in Dark Peak Books (93 High Street West in Glossop), or via the Cabinet of Curiosities shop (here). Or you could track me down and snag a copy.

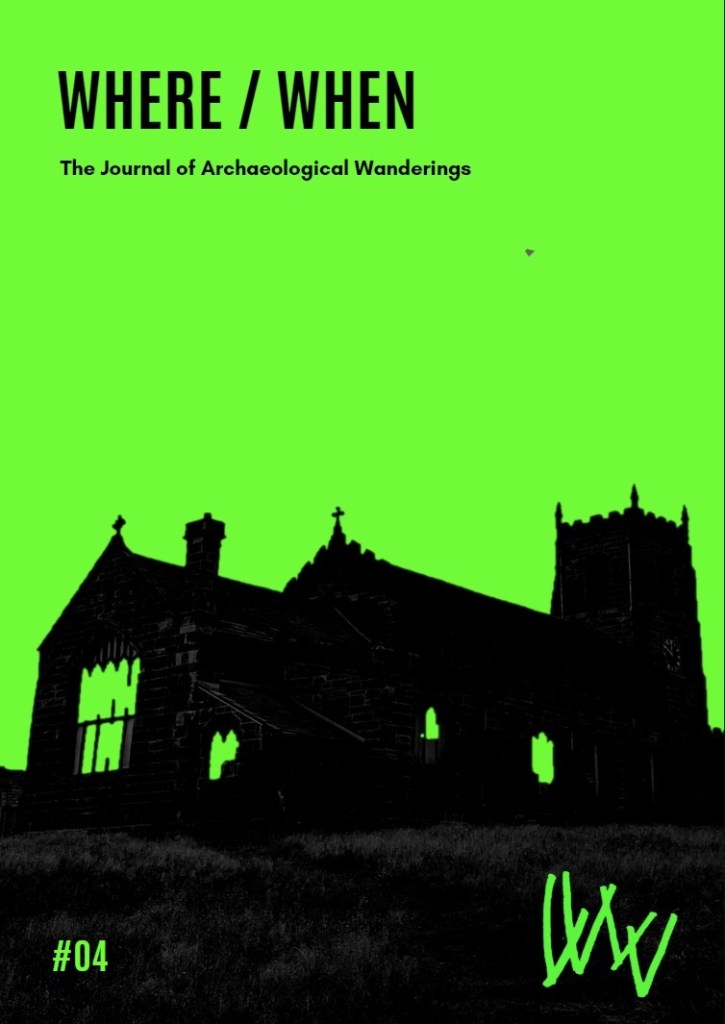

For those of you who are unaware, Where/When is a quarterly journal of Archaeological Wanderings. Essentially, a walk in the Glossop area, with yours truly chiming in about the archaeology and history of where you are wandering; think a pinch of pottery, a hint of psychogeography, some groovy photographs, a dash of discovery, a toe stub of psychedelia, and a splash of the usual Glossop Curiosities shenanigans. No.3 Takes us on a walk from The Beehive in Whitfield to The Bulls Head in Old Glossop via medieval trackways, a Saxon stone cross, 18th century buildings, and a 10,000 year old glacial erratic boulder. Marvellous stuff!

And Where/When No. 4 is in preparation; titled “The Melandra Meander“, it will detail a circular walk from Melandra Roman Fort to Mottram Church on the hill above – via Hague and medieval trackways – and then back again, and is full to the brim with the kinds of historical and archaeological goodies that you have come to expect. It’ll be in stores in December, just in time for Christmas.

I have a whole pile of ideas for Where/When, and the Cabinet of Curiosities in general… all kinds of stuff: t-shirts, anyone? Art prints? The Rough Guide to Pottery in booklet form? And in particular I’d like to start a series of monthly guided Wanders – where you and me can Wander together. Let me know what you think about this. Or indeed anything about the website, or what I have written. It’s nice to know I’m not just shouting into the void!

Right then, apologies for the late post of this article, and for generally being behind in most things – there’s often a lot less of old TCG to go around than I believe, so I end up dropping some of the things I’m juggling. More soon, I promise.

Until then, though, please do look after yourselves and each other, and remember – a person might look ok on the outside, but can be struggling inside. We all matter.

I remain, your humble servant,

RH