What ho, people! What ho!

I know, I know! Another instalment of the seemingly never-ending Rough Guide… it really is the gift that keeps on giving, isn’t it! I can see and hear the hubbub from here. The yelps of excitement, the whoops of joy, the screams of happiness… lots of these. And the exuberant dancing in the street. It even looks like people are running away from me… what fun! And oh look, that man over there has started drinking what looks like cheap vodka from a bottle, and is shaking his fist at me in a cheerful expression of his enthusiasm. Steady on, there’s a good chap…

So then, today’s offering is simply black pottery.

At most places you encounter pottery, you will find sherds with a black glaze on them. Of varying quality, and of various sizes and forms, there is always a background noise of them, as a wander through the archives of the site will show. It’s less common than the Blue and White stuff, but you will find it. Most often as a big sherd of a thick walled vessel – a chunky rim if you are lucky – but more often featureless body sherds that feel like they ought to be able to tell you something… but don’t. Mostly these are difficult to date; one black sherd looks very like another, and without having the whole vessel to look at, it can be futile to try – even I just mentally lump most of them together under the banner ‘Victorian’. And largely I’d be correct (as if you ever doubted me!). But… actually there are subtle differences that can give a little more information and provide a rough date.

The problem is that Black glazed pottery is just that. Pottery… with a glazed black surface. So you can see how assigning a date to it might be a tad difficult, and whilst there are some broad observations to be made, the finer points of interest are missed. It has taken me this long to fully wrap my head around it, and I think I have it straight, though even now it’s fuzzy in places. I don’t like ‘fuzzy’. I like things to be simple and logical and straightforward, with neat edges and exact dates. Today’s offering has none of that and is full of fuzzy, which frankly makes me feel a little uncomfortable (does anyone else feel that these little interludes are starting to sound like a therapy session? What do you mean “we know you’re a raving lunatic, get to the pottery”… honestly). No, they are a problem, and quite rightly most people shy away from them; I mean to say, these bally Herberts frighten me… I can only imagine what your normal non-sherd-nerd would make of them. No… by and large it’s safer to just leave them. Unless, of course, some lunatic tries to impose some form of order on it, and takes a trip to the dark side in order to investigate Black Glazed Pottery.

Well… cometh the hour, and cometh the lunatic.

The following is a rough outline of what, where, and when; it isn’t final, it can’t be applied as a law, and certainly not everywhere, and there are always exceptions, and always overlaps. Indeed, we can only speak here of a pottery making ‘tradition’ rather than clean-cut specific ware types, and people have been making pottery in a black-glazed tradition for over 500 years. But it will allow you to look at your black sherd and say “oooh, that’s probably a…”, which is sort of the point of this guide (no, Mr Shouty-Outy, despite what you think, the point of this site is not to attempt to be “the dullest thing on the internet“, thank you very much).

So, we start today somewhere in the 15th century, which is nice!

CISTERCIAN WARE

DATE: 1475-1600-ish

DESCRIPTION: Fine, hard-fired, purple or reddish purple fabric, with a very dark brown to black glazed surface interior and exterior.

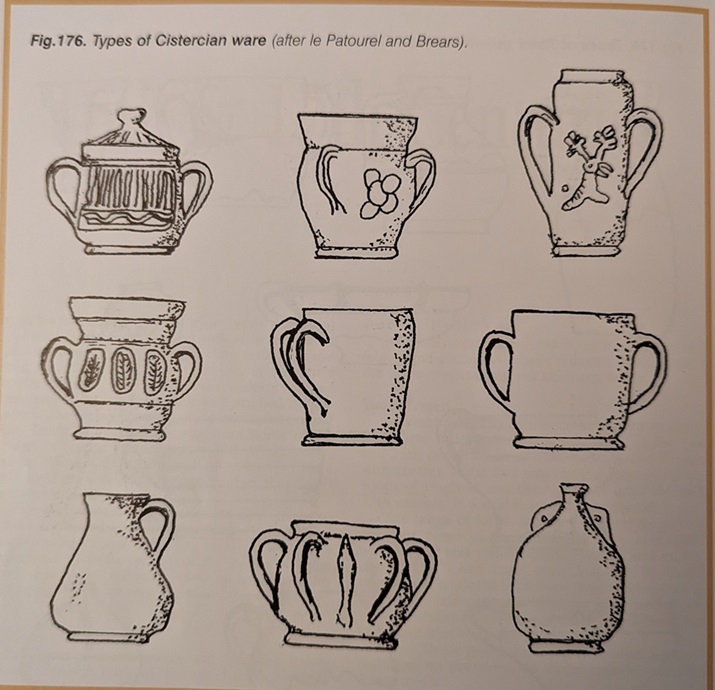

SHAPES: Mugs, Cups, Tygs, Small Jugs.

This is the first black glazed pottery type, and overtakes Tudor Green Ware as the pottery type found on early Post-Medieval sites up and down the country. It’s origins are unclear – as a tradition it is unlike anything that went before it, and was the technological and design cutting edge. It was originally thought of as being made in Cistercian monasteries in the north – hence the name – it is now known to have been made all over, most famously in Wrenthorpe (West Yorkshire) and Ticknall (Derbyshire).

Characterised by a very thick all over (interior and exterior) iron rich glaze which produces a very dark brown or black surface when fired.

The glaze is shiny, but has a dullness to it – also very characteristic – and is often fairly poor quality, with pitting and an orange-peel surface, and is often sloppily applied, leading to melted blobs on bases, etc. – it’s still very much in the medieval way of doing things.

Very rarely, there is a pale cream decoration applied in slip, often in blobs or rough images of unicorns or other designs.

The fabric is also very characteristic. Very hard fired (almost vitrified), it is a purple, greyish-purple, or reddish/brownish purple colour. Looking closely at it, you can see voids formed by gases during firing, and very infrequent quartzite ‘sandy’ bits.

Shapes are mostly drinking vessels – mugs, cups, and tygs (multi handled cups) – with a sprinkling of small jugs and bowls; the emphasis, though, is very much on the stuff that cheers! Handles are often small and delicate, and normally flat.

I am lucky enough to own a copy of a Tyg by potter John Hudson, an amazing craftsman who used traditional techniques to faithfully recreate medieval and post-medieval vessels:

The making of this ware type – with this specific fabric type and in these shapes – seems to have died off by the late 1500’s, but the black-glazed tradition continues.

BLACKWARE (aka Midlands Black Ware, Black Glazed, Ticknall Ware, etc. )

DATE: 1550-ish-1800-ish

DESCRIPTION: Black shiny glaze over a red or reddish brown fabric.

SHAPES: Mugs, Jugs, Tygs, Bowls, Dishes.

This stuff continues the tradition of making pottery with a lustrous black glaze, but without the hard purple fabric. Instead, reddish, reddish-orange, or occasionally buff coloured fabrics are found, and overall it is fired to a lower temperature, making it less hard and more, well, coarseware-y. Often with a small number of quartzite – sandy – inclusions, but normally of a consistent colour throughout.

The surface is normally much shinier than Cistercian Ware, but can also be found as a metallic looking surface, the result of adding lead in the form of Galena. Often there is an under-glaze slip that provides a red surface which, when covered in the glaze and fired, creates the black surface. This is particularly true in the case of the buff or whitish coloured fabrics such as that in the photo above.

It has been suggested that this was a desired effect; in the poor candlelight of the 17th and 18th centuries it might look like it was made from more expensive pewter. This is a Skeuomorph, an object made from one type of material made to look like it is made from a different material; we’ve encountered it before in the Manganese Mottled Ware pottery. I’ve said it before, but don’t say we don’t learn you nuffink on this website!

Shapes include many of the same type you find with Cistercian Ware – mugs, tygs, jugs, etc. – although slightly more evolved – for example the mugs and tygs are noticeably taller. However, we now see larger bowls and jugs, too. Blackware becomes the utilitarian ware type, and thus it takes on many forms and uses.

To be honest, there is a deal of overlap between Cistercian Ware and Blackware, especially at the beginning, and it is not an exact science. Moreover, it is a good example of problems within post-medieval pottery studies: many different potters are making this stuff, in many different locations all over Britain – the black glaze was very popular, and so there was a ready market. But, 100’s of years later we have archaeologists digging this stuff up everywhere, and mudlarks/tiplarks/fieldlarks finding it all over. But there is no consensus as to what this stuff should be called! And why would there be? It is made everywhere, is found everywhere, and comes in so many different forms. In fact, I only call it Blackware because the last article I read called it that, and I like the name – it is helpfully vague in that it doesn’t rely on a geographical place (Ticknall Ware, for example), or a specific vessel shape (Pancheon Ware), to define it, but it is specific enough to describe what it is. See… fuzzy edges! I’m feeling very uncomfortable… I need a bracer!

The vast majority of the stuff you might find will be in the later part of the date bracket given above – late 17th/early 18th century. Indeed, by about 1720 the Blackware tradition starts to decline, although it probably continues until the end of the 18th century. Whiteware has become the pottery type – white is the new black, and all that – and we see that start of the quest for the perfect white surface that I have talked about before. To be fair, it was dying from the mid 1600’s onwards, with the introduction of the classic post-medieval pottery types – the Manganese Glazed and Slipwares.

Well, I say dying. Actually, and more specifically, the thin-walled vessel Blackware pottery tradition tails off, but it continues to be used on Pancheons.

PANCHEON WARE (Coarse Earthernwares)

DATE: 1700 ish-1900 ish… emphasis on the ‘ish’!

DESCRIPTION: Thick-walled (1-2cm), often reddish/orange coloured fabric, commonly with a black internal glaze, and with a chunky rim.

SHAPES: Well, er… Pancheons, but also other large utilitarian vessels: large pots, colanders, chamber pots, etc.

A lovely word, for a great category of pottery – the mighty Pancheon – also described as mixing bowls, cream separators, or dairy bowls. Their purpose is multiple, as their name suggests, but it is their large size that is really impressive, as is the skill, detail, and indeed general lack of care with which they were made and decorated. Into this category we might also add large bowls, large dishes, chamber pots, and colanders. But the commonly encountered type, Pancheons, are generally steep sided open bowl shapes, with a height of up to 30cm, and a rim diameter of up to 60cm, or more. They are big pots, and consequently the sherds, are usually thick walled, ranging in width between 1 and 2cm, and are instantly recognisable.

Fabric is normally reddish or reddish brown.

Commonly, though, the fabric is poorly mixed with another cream or buff coloured clay, giving it a distinctly marbled effect.

Why this was done is unclear. If it was just a few examples of this happening, we might suggest that the potter was using up some spare clay he had lying around, but it is too commonly found. It can’t have been a decorative reason as no-one would see the fabric unless the pot was broken. I wonder if it was a practical concern, and that the buff clay had different thermal properties, perhaps allowing the vessel to shrink uniformly when drying or during firing? This might explain why it was poorly mixed into the fabric. But honestly… answers on a sherd to the usual address. My feeling, though I can’t be certain, is that this was more commonly found in earlier vessels, and that these mixed clays stopped being used in the 19th century.

Within the fabric are often found small inclusions – sometimes quartzite (sand), sometimes other small stones, and occasionally grog – crushed fragments of pottery. These too have the effect of improving shrinkage during, and strength after, firing.

Vessel rims are very distinctive – thick and chunky, and often square-ish in section, although other forms of rim – particularly those from shallow dishes – are flatter. Again I suspect, but can’t prove (yet) that these are early vessel types, and that by the 19th century the Pancheon takes on a single uniform shape which is made by potters all over the country.

Some Pancheons have handles, and often these are scooped lug type handles.

Perhaps most distinctive is the black glazed surface. Because these vessels were normally only glazed on the interior, you will only find it on one side. As with the Blackware above, the dark colour was achieved by roughly painting a red slip on the interior and the rim, over which was applied a thick iron-rich glaze which, when fired, becomes the very dark brown or black we see. Sometimes this red slip was applied to the whole vessel, but even then any glaze or slip on the rim or exterior is the result of spillage.

That said, sometimes this spillage was a deliberate decorative feature, with the large exaggerated thick drips over the rim and down the outside giving it a certain devil-may-care look.

This devil-may-care look also extends to the interior and exterior surface treatment of the vessels, where they also make use of ‘manufacturing’ marks as a form of decoration, thus you can see deep grooves and ridges on the interior and exterior where the clay has been pulled up on the wheel, and roughly made smoothing marks on the exterior.

Indeed, overall they seem to be very roughly made, with little attention to ‘perfection’ at a time when pottery was fast becoming quite literally an art form. I suspect that this is in part due to speed being the essence in making them, combined with the fact that they are entirely practical with very little attention paid to decoration. Even the fact that they are glazed on the interior only is suggestive of their practical nature – it’s quicker to glaze only one side, and it is cheaper, but it is also not necessary to glaze the exterior as only the interior needs to be waterproof. However, I also think there was a decorative element to the roughness – the exaggerated drips, the course smoothing, the noticeable finger and thumb marks in the wet clay and slip. I like this, it adds character and a human element.

Now, whilst most sherds you will encounter are Black glazed, within the broad category of Pancheon Ware are sub-types, with different coloured exteriors – namely Brown, Yellow, and Pale Yellow/Cream.

Actually, the colours depend on the amount of iron in the glaze and the colour of the surface underneath, but it is all the same process. It works like this: the more iron you add to a glaze, and the darker the surface under the glaze, the darker colour the pot will fire. And conversely, the less iron you add to the glaze, and the lighter the surface under the glaze, the lighter the finished pot will fire. So the Yellow glazed sherds often have a white slip and a glaze with little iron in it, and the Cream, too, but with a glaze that has even less iron added to it.

Brown has a darker coloured red fabric or a red slip, and an iron rich glaze, but not as iron rich as the Black glazed surfaces.

The truly wonderful Bingham Heritage Trails Association, who have done an amazing amount of work on post-medieval pottery (a very much recommended website full of pottery), have given them different names, and put them in a tentative chronological order, depending on fabric types and surface colour. This might work, but I’m not 100% convinced, and I think the differences maybe have more to do with desired colour, geographical origin of the clay, and our old friend fashion, than the date it was made. Essentially, any colour/surface treatment could have been made at any stage between 1650 – 1900… ish. I am always happy to be wrong, though – its the story of the pottery that matters.

The fact that Pancheon fragments crop up everywhere is both testament to their popularity – at one stage everyone seems to have had one – but also their large size; there’s simply more of it, so when they break up, they produce many more sherds than, for example, a smaller plate would.

Overall, it seems that Pancheons – and indeed all of these large domestic vessels – stop being made, or at least stop being popular, at around 1900 (although I’m sure many would still be in use from then on). Why is unclear, but it may simply be that the large clunky vessels were impractical in most kitchens, particularly in the cramped interior of terraced houses in the cities, and so they fell out of favour.

Our final black glazed pottery type is…

JACKFIELD WARE (aka Shining Black)

DATE: 1750 – 1820-ish

DESCRIPTION: Very shiny black surface on a red earthernware fabric. Often has handpainted white decoration.

SHAPES: Very tea/coffee focused, so teapots, coffee pots, sugar bowl, cups, jugs, mugs, creamers, etc.

Not common at all (I only have one sherd!), Jackfield Ware is a refined earthernware that was popular for a short period in the late 18th century, and was focused on the consumption of tea and coffee, incredibly fashionable at that point in time. It reproduced all the essential elements of the black glazed tradition, but did so to an almost perfect finish. It is named after Jackfield in Shropshire, where it is known to be made, but the majority seems to have been made in Staffordshire. I have to say, this stuff is almost impossible to identify as a single sherd – it looks very like all the others, perhaps just a bit finer. If it wasn’t for the painted decoration on this example, I wouldn’t know I had any at all!

Fabric is red or a reddish brown, hard fired, with almost no inclusions – it is refined, and dense, and the vessels are thin walled.

The surface treatment is a uniform black glazed interior and exterior, with the glaze being particularly shiny – almost metallic – probably due to a high lead content. Honestly, you can see your reflection in this stuff. There is often sprigged decoration (a separately moulded clay three dimensional design stuck on the outside – often, in this case, floral designs – flowers, grapes, etc.), but commonly there are hand painted designs. These images were painted after the vessel was fired – over-glaze decoration – as contemporary under-glaze paint wouldn’t survive the firing process. As a consequence they often rubbed off, and exist as ghost-like images, especially in the kind of sherds that we find.

In terms of manufacturing, you can see the grooves where the potter pulled the clay up, but only on the interior wall where it wouldn’t be seen – this is fine pottery after all – whilst the exterior is super smooth, and is usually turned on a lathe to produce a perfect finish.

Shapes, as I say, are dominated by tea and coffee consumption, so commonly there are teapots, coffee pots, and cups.

The cups are more like those we would recognise today in that they have only one handle, rather than the multiple handles of the tyg – a design development. This is the start of modern pottery… raise a toast with your next cup of tea!

And to end with, a broad description of Midlands Purple Ware, a slightly coarser version of the fabric that Cistercian Ware is made from.

MIDLANDS PURPLE WARE

DATE: 1400-1700 ish

DESCRIPTION: Hard fired coarsish pottery, purple-brown/grey in colour. Coarse surface, normally slipped with wiping marks. Occasional internal dark glaze.

SHAPES: Large open vessels, bowls, urns with spigot hole, salt pans, butter pots, rarer in small vessels, cups, mugs, etc.

Not commonly encountered to be fair (I only have a single, if large, sherd), but it is occasionally found in small quantities on early sites, and is part of a story. Midlands Purple straddles the period between the medieval and periods wonderfully, and takes elements of both.

Made in the same potteries and kilns as Cistercian Ware, and indeed the larger Midland Purple vessels were sometimes used as Saggars (a protective ‘box’ within a kiln) for the smaller and more delicate Cistercian Ware vessels. Thus we can be sure that the two ware types were contemporary, and Cistercian Ware seems to share the fabric type – that is, both ware types are made using the same clay, and fired at the same temperature, to produce a very similar type of fabric.

Purple, reddish purple, or greyish purple in colour, the fabric is hard fired, almost vitrified, with numerous voids, and has numerous quartzite inclusions, often with a black and white “salt and pepper” like colouring.

The surface is purplish, greyish purple or a browny purple, and is usually slipped, or simply smoothed, and smoothing marks are normally visible. The inclusions also poke though this slip, giving the surface a coarse feel. Rarely it is glazed on the interior, and these are normally found on butter pots, used to export butter into the big cities, notably London. A common shape is that of a jar with a reinforced bung hole just above the base, and these are often associated with domestic beer making, with the holes taking a spigot. Shapes include jars, butter pots, storage jars, jugs, pipkins, bowls, mugs… in fact a huge range of vessels, but the large jars and butter pots are the most common.

Traditionally, MPW is though of as dying out by the late 17th century, when it’s role as the hard-wearing utilitarian pottery type was probably overtaken by the aesthetically more pleasing Brown Stonewares.

So there we have it, Part 10. I’m pretty sure people who have spent long years studying one type of black glaze from a single pottery workshop are currently forming angry mobs, complete with lit torches and pitchforks, to seek me out, but I hope it helps.

The bad (good?) news is there’s only two more parts to the Rough Guide… Finewares and “Things That Might Be Pottery… But Aren’t”. The good (bad?) news is that I’m going to try and edit this guide into a Where/When Special booklet or zine, so that you can take it with you when you go Wandering. I know, I know… you can’t wait.

More very soon, as I have some big announcements! *Cough Wanders-a-plenty *Cough… and more.

Until then, please look after yourselves, and each other – just a quick check in with the neighbours, or even the person serving you in the shop, can make all the difference.

And I remain, your humble servant.

TCG