I gave a talk to the wonderful folk at the Glossop and Longdendale Archaeological Society on Tuesday night, on the subject of Whitfield Cross. I was honestly really quite nervous. Like most people, I am genuinely scared of speaking in public, and it’s not a thing that comes naturally to me. Indeed, research seems to show that people are more frightened of public speaking than they are of death – that is, they would rather be in the grave and dead, than standing over the grave and delivering the eulogy. However, I went ahead and did it – feel the fear, and do it anyway… as the rather cliched saying goes.

I think it went rather well, thankfully. Hopefully.

Anyway, here is the edited-for-blog transcript of the talk. It builds on the original Whitfield Cross post, but has lots of new information and photographs… so please read on, even if you have read the original.

I live in Whitfield.

For those of you who don’t know, Whitfield is a distinct area within Glossop, and was mentioned in the Domesday Book as a separate settlement from Glossop (as Witfeld), and remains a parish in its own right.

Now, my local pub is The Beehive, on Hague Street at the top – highly recommended, by the way – but in order to get to it, I had to walk up the steep hill of Whitfield Cross.

And every time I did, I pondered the name. Whitfield Cross is an odd name for a road that has no cross on it. I vaguely thought to myself, there must have been a cross here or somewhere nearby at some stage, but after a cursory scan on the internet, and a rifle through the local history section of the library, I drew a blank regarding the history of the cross. I must state that I hadn’t yet come across Neville Sharpe’s excellent book ‘Crosses of the Peak District’ which does have an entry for it, albeit a very short one.

However, sometime later whilst delving into the history of the area, I came across an article by our old friend Mr Hamnett entitled “Botanical Ramble to Moorfield”, dated to about 1890.

There is not much botany, but it is an absolute goldmine of local history. And as I read the article my jaw dropped. I’m going to read you the relevant part here, as it captures perfectly what makes Hamnett so good. Plus the language is great!

“In the latter part of the last century the Cross Cliffe lads planned and partially carried out what was to them a most daring and audacious deed. One ”Mischief Night” the eve of the first of May, it was resolved to steal the Whitfield Cross. In the depth of night, when all was quiet, and the Whitfield lads were slumbering or dreaming of their “May birch”, the Cross Cliffe invaders came and detached a portion of the cross. With secrecy, care, and much labour, it was conveyed away nearly to its projected destination, but the exertions required for the nefarious deed had been under estimated, their previous work in removing all articles left carelessly in the yards or at the back doors of the good people of Cross Cliffe and neighbourhood, such as clothes lines, props, buckets, etc., etc., to their “May birch” had already taken much of their energy out of them, and, coupled with the steepness of the ascent to the “Top o’ th’ Cross,” distance and roughness of the road to Cross Cliffe, and the weight of the stone, they were reluctantly obliged to abandon their “loot” in the last field near to the pre-arranged destination. What the feelings were of the Whitfield lads on discovering the desecration and loss of a portion of their cross can be better imagined than described. The stolen portion remained in the field for some years. Mr Joseph Hague, of Park Hall, was solicited to restore the cross to its original form and position, but being imbued with a little Puritanism, he refused, and the other portions gradually disappeared until there is nothing left of the Whitfield Cross, except the stolen portion, which is now part and parcel of a stile in a field at Cross Cliffe, where the then tenant of the field placed it, over a century ago.”

“Blimey!”, I thought!

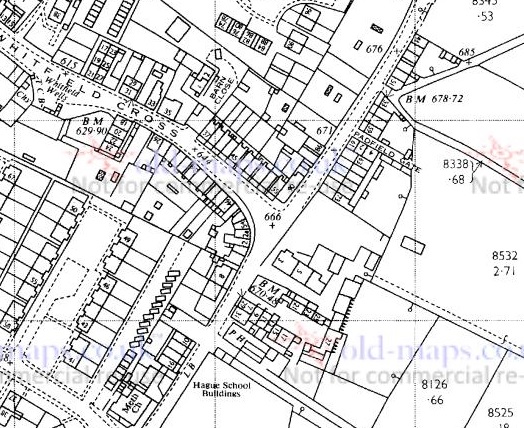

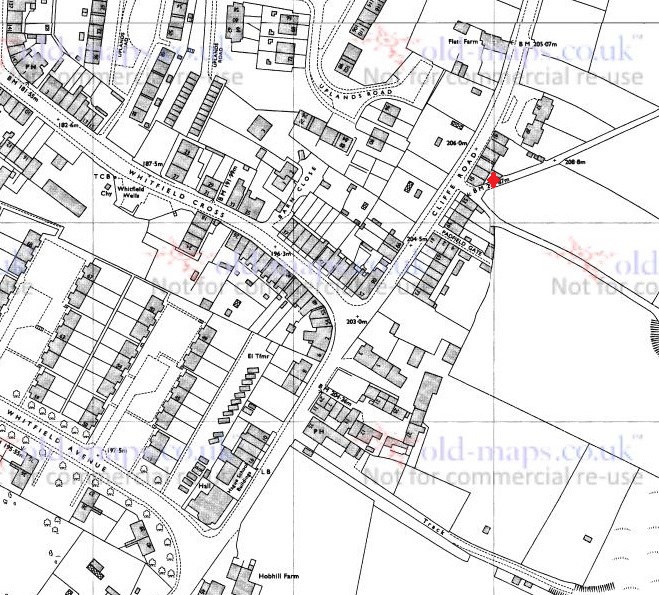

Date wise then, the removal of the cross would have been 1790 or so, and the cross would have originally stood at the junction of the road Whitfield Cross and Hague Street/Cliffe Road but we shall return to that in a minute. Cross Cliffe is at the top, along Cliffe Road, and it extends further off screen.

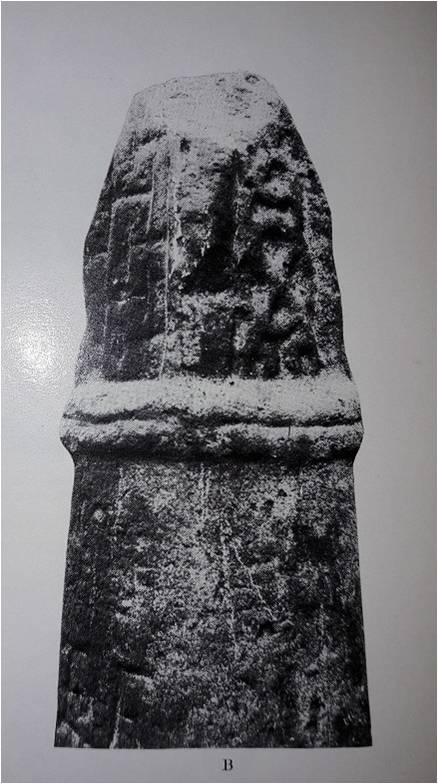

Upon reading this passage I quite literally pulled on my boots and headed up to Cliffe Road and went exploring. Alas, not knowing exactly where the cross was – and it is not marked on any OS Map that I have seen – I failed to find it. Weeks later, however, and walking for pleasure rather than exploring, I by chance took the correct path… and this was the sight that greeted me.

Now, I know what you’re thinking… what exactly is it?

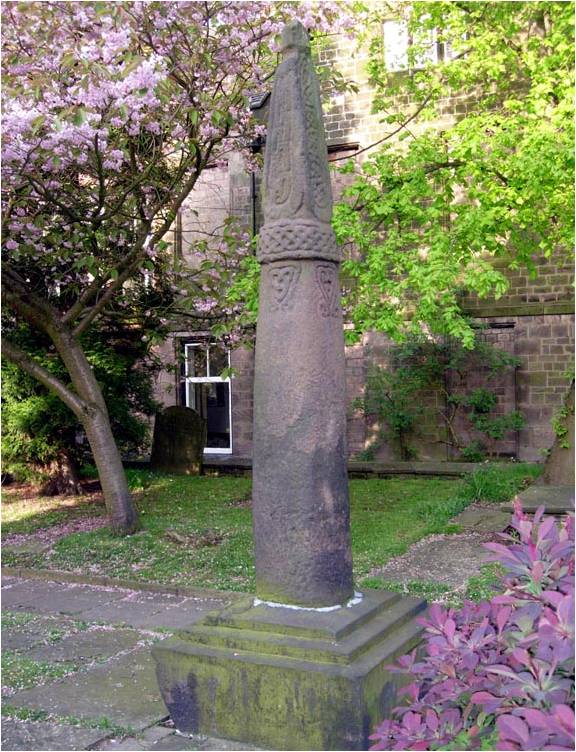

Well, it’s a 9th, or more likely 10th , century Anglo Saxon stone cross of a type known as a Mercian Round Shaft or Mercian Pillar Cross. There are roughly 30 known examples, with doubtless quite a few more waiting to be discovered. Originally though… who knows. Hundreds? Thousands?

Most stone cross shafts are square or rectangular in section. The Mercian variety is defined by its round or slightly oval shaped shaft. It’s difficult to understand exactly what the crosses would have looked like from the Whitfield example alone – it is particularly worn and has been defaced. However, although no complete examples survive, by studying the better preserved examples we can begin to build up a picture of how they would have looked.

So then. There is the defining characteristic shaft.

Round or slightly oval in section, and usually under 5ft in height, although some, such as that at Cleulow in Cheshire, reach as high as 7ft.

The shaft is normally plain and undecorated, although examples exist where this is not the case – Leek and Blackden for example.

A notable example is at Brailsford, where we can see a seated solder holding a sword.

The shaft tapers to a single, or more commonly, double band or collar that runs around the shaft.

This band is not normally decorated, although at Leek, and elsewhere, it is (see above photograph for detail)

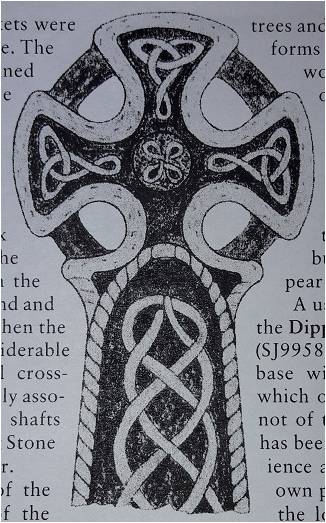

Above the band is a rectangular neck that is more often than not missing. Where the neck is present, it is normally decorated – often simply, but sometimes with complex knotwork and rope motifs such as these examples from Disley.

On top of this neck the cross itself would have sat. Fragments, such as those from Disley, allow us to reconstruct the cross head – it would have been a ‘wheel’ type with four arms and a central boss, perforated, and probably heavily decorated with rope and knot motifs.

So, with this in mind, let’s look more closely at Whitfield Cross.

We can see immediately it is very worn. The shaft, made from the local millstone grit, is a lightly flattened round shape in section, and tapers slightly up to the collar. The collar is, at first glance, a single band. But, with the eye of faith, I think I can detect a groove running around its centre, meaning it would be a double.

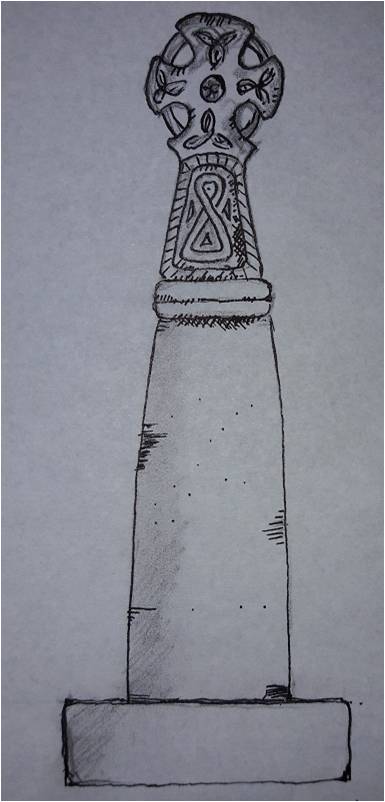

It is worn, but I think would have originally been something like this.

Back to Whitfield Cross, we see the neck is worn almost beyond recognition, surviving only 6inches above the collar. However, and again with the eye of faith, I think I can detect the remains of knotwork or similar decoration.

The depressions you can see on the neck are possibly the remains of the hollow parts, the relief, of the knotwork decoration. Look again at the photographs above, and then compare with the Macclesfield example above – you can clearly see the relief work and how it would look if it was worn.

As for the cross head… we have no clue. Instead, we must rely on Sharpe’s reconstruction for guidance.

So then, and apologies in advance for the rather bad penmanship on my part – I am a good technical drawer, but an awful artist – here is my reconstruction of how the cross might have originally looked, assuming all the ‘eye of faiths’ are correct!

So then, further questions are raised – the first of which is, well… what is it?

It’s a cross… obviously, but what is the meaning of it, why was it carved, and why is it here?

The urge to leave a mark in the landscape is undoubtedly a universal feeling, and one that has been with us since we humans first started ‘thinking’. Stones have often been used to leave this mark, to somehow own the land, and to act as a focus, I’m thinking prehistoric standing stones, here. Stone crosses are very much a continuation of this act of permanently stamping yourself into the landscape.

But they can convey much more information.

They were often placed as boundary markers, showing where parish, territory, hunting rights, farmland and such begin and ended. Indeed, there are many stone crosses in the area that do just that. They act as a reminder of the adoption of Christianity in the area, a symbol stating loudly that “we are Christians”. It may also have been used as a gentle reminder that “you are Christians, now” as certainly in the early Saxon periods, and with the later Scandinavian incursions, the old pagan Gods were never far away, and it was far from certain that Christianity would prevail.

However, if we look again at where the Cross originally stood, we can see another, more practical, purpose for the cross – that of marking an important junction in the contemporary roads.

So, we have the old pack horse route that comes from the south – Peak Forest, Buxton, and Chesterfield – to Old Glossop, and on to Woodhead and Yorkshire, beyond, and now called Hague Street/Cliffe Road. The cross would have marked the junction of the track that went along Whitfield Cross and Hollincross Lane, and onto Simmondley and beyond. There was another spur coming out along what is now Gladstone Street, leading to that area of what is now the town, and again onto Woodhead.

It has been suggested that some roadside crosses were placed as a gift of thanks for the completion of a safe journey, effectively a votive offering in payment for an answered prayer (i.e. help me get home in this awful weather, and I’ll set up a cross to say thank you). They might also function as a spiritual fortifier, reminding the traveller of God’s watchful eye and his protective power over the faithful. It is easy, I think, in these days of surfaced roads, street lights, and large settlements, to forget just how dark and treacherous travelling in the pre-modern era was – making your way from A to B in total darkness, along a muddy track, and with no map as such, and knowing that if you took a wrong turn somewhere, you were lost.

There is also a further, more subtle, reason, too for the cross being here. Actually, one that perhaps wouldn’t have been that subtle when it was first carved and erected, and this reason is tied in with another important question: Who made it?

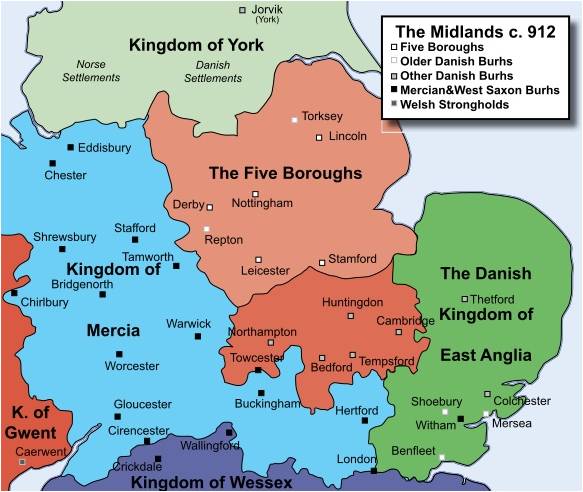

It is known as a Mercian round shaft because it occurs only in the Anglo Saxon kingdom of Mercia. However, that is to massively oversimplify the answer, and it is more complex and more interesting than that.

Mercia was for a time, the dominant kingdom in Britain, but by the 9th & 10th centuries it had lost that dominance to Wessex. Even so, we can see that the kingdom is still a massive area. The occurrence of these particular cross types is confined almost completely to the northern part of the kingdom, and specifically where we are now – north west Derbyshire, east Cheshire, and northern Staffordshire: in short, the Peak District.

One of the smaller kingdoms absorbed by the Mercians was that of the Pecsaetan, literally the people of the peak, and who probably gave their name to the Peak District. They seem to have been a distinct tribal grouping, relatively autonomous, but owing tribute and allegiance to the King of Mercia. Interestingly, the land upon which the Pecsaetan farmed and lived, coincides precisely with that in which the crosses occur – Northern Mercia.

I am speculating, obviously, but it is possible that this specific cross type is a product of the people of Pecsaetan kingdom, or at least what remained of it. Moreover, this was at a time – the 9th and 10th centuries – when the Mercian dominance was on the wane – just the time that a little national pride would be in order. And thus, we may speculate that the cross – a region or people specific type – might even have become a symbol, or totem perhaps, for the Pecsaetan kingdom.

There are other examples of Mercian Round Shafts in the area. As I say, there are about 30 known crosses, give or take – there seems to be no definite number recorded, and doubtless there are more waiting to be uncovered. I note that the Derbyshire section of the book series the ‘Corpus of Anglo Saxon Stone Sculpture’ is due to be published, but without having a spare £100, I’ll have to wait until the library gets a copy to check what it says about the crosses.

Our nearest examples are Robin Hood’s Picking Rods in Ludworth, roughly 3 miles south west of Glossop.

Originally known as the Maiden Stones, these are an example of a double cross, that is, two crosses set up side by side. This seems to have been a feature peculiar to the Mercian Round Shaft, but it is unclear what the purpose or meaning of this was. The Picking Rods sit on the parish boundaries of Mellor, Ludworth, Thornsett, and almost that of Chisworth. Perhaps then, the fact there are two of them may be related to their importance in marking this out – with two different parishes choosing to erect a cross each. Another possibility is that they were originally two separate crosses, but were brought together at some stage in the past – with perhaps one of them originally marking the parish boundary for Chisworth.

There is another pairing of crosses to be found in Disley, some 10miles or so south west of Glossop.

These too have no obvious reason behind their pairing, and although they have been moved from their original site, the old, double, cross base is still there marking the place.

Other, single, examples of Mercian Round Shafts are to be found at Macclesfield, Fernilee, Bakewell, Alstonfield, and notably Leek. Importantly, at Bakewell and Alstonfield, there are large numbers of cross shafts and heads, which, suggests Neville Sharp, may be where some were made and distributed.

What then, does the cross tell us of Glossop in the so-called Dark Ages?

Sadly, not very much. The post-Romano-British period is massively under-represented in the area, to a point where it is virtually non-existent – there is the possible glass bead from Mouselow, and that is about it. And yet we know something was here as Whitfield, Glossop, Chunal, Hadfield and Padfield are all mentioned in the Domesday book – they are clearly important enough to be counted. There is also the possibility that All Saint’s church in Old Glossop has a Saxon origin, but that is currently unproven. Neville Sharpe in his book Glossop Remembered suggests that the lack of a Saxon presence in Glossopdale may be due to a lack of interest and funding by local landowners prior to the area being industrialised. This may be the case to a point, but we do see Roman material coming to light from that point in Glossop’s history, so where is the Saxon?

No, seemingly all we are left with is the monuments – Robin Hood’s Picking Rods… and Whitfield Cross.

What the cross can tell us, though, is that Whitfield, and by extension Glossopdale as a whole, was clearly in contact with other areas of Mercia. There was no mass media, and so the particular style of cross – the Round Shaft – could only have been communicated and spread through contact and travel. Even in this insular and provincial northern part of the kingdom of Mercia, it seems that the Glossop area was very much a part of the greater Anglo Saxon world with access to all that that brought.

And there it sits, a single monument to the late Saxon inhabitants of Glossop – the most tangible connection we have with the residents of the area at that time.

And sadly one of the most overlooked.

I would love to see the cross moved from its present location and placed somewhere where it can be seen and understood by everyone, as a vital part of the heritage of the area. I have suggested before that the wells on Whitfield Cross, the road, would be ideal, but that is a project for the future.

Thanks for reading, and apologies for the lengthy post. As always, any comments, questions, or corrections are very welcome.

RH