Welcome, welcome, one and all. I hope you are all well, and that in these uncertain times you are staying safe as we stumble towards something approaching real life. Today’s post does something I try not to do very often: it strays from Glossopdale and Longdendale. Don’t panic however, we’re still in Derbyshire. Marple Bridge to be specific. And there may be a link to Mottram, so there’s that. And quite frankly this story is just too good to miss.

I was looking through some online sources a while back, specifically the ones posted on the North West Derbyshire Sources website. There’s all kinds of interesting primary historical sources published there – censuses, trade catalogues, personal recollections, etc. and all of them are for this area – Glossop, Charlesworth, Hadfield, Hayfield – it’s well worth checking out, a truly award-winning website. One of the sources for Charlesworth is the diary of a certain George Booth, dated between 1832 and 1834. The diary is not perhaps what you would describe as the most riveting record of life in a small village; typical entries are very short, personal, and along the lines of “Today and yesterday I have been building a wall as a spur against the weir” (April 11th 1832) and “Daniel Thorneley’s wife died today” (April 28 1832), but these are recorded history, and for this it is invaluable. Certainly, the wall against the weir isn’t important in the grand scheme of history, but it provides us with the date and a personal record of who built it, and why – and these are surely the aims of all historical and archaeological inquiry? And it is these little snapshots – who built what wall, who moved house where, crimes committed, the price of pork, and tales of fire, flood, and cholera – that escape the archaeological record, making the diary an invaluable source. Here, read it for yourself, you won’t regret it.

And of course, although it is Charlesworth/Chisworth based, Mr Booth wanders all over the area, to Glossop, Gamesley, Chinley, Marple Bridge, Broadbottom, and beyond. It was one of these entries that caught my eye:

3rd May 1832

A Stone to commemorate Matlock’s Leap was fastened in the wall by the river side a little above Marple Bridge on the Derbyshire side, on this occasion there was a Mare [Mayor] chosen (I suppose the first Mare there ever was at Marple Bridge of this sort) and a regular Mare’s Walk consisting of the Mare (John Kirk) and a great many of the neighbouring Gentlemen after the walk the partook of a good Dinner at one of the Inns. which was paid for out of a subscription raised for that purpose this took place last Easter Monday.

So what was Matlock’s Leap? And why was it so important that it required a stone and a slap up meal to celebrate it, and particularly on a bank holiday Easter Monday (it would have been held on 23rd April 1832), and at the same time as choosing a mayor? Clearly it was so familiar to George Booth that it required no further explanation – it is almost a throwaway comment. And yet, the phrase “Matlock’s Leap” typed into Google provides just one relevant hit. It turns out that whilst the mystery was relatively easily solved, it is nonetheless quite a tale, and there may be yet more to be uncovered.

The single reference to the ‘leap’ is in ‘Cheshire Notes and Queries‘. This Victorian weekly periodical allowed readers to post questions of a historical or literary nature, and others to answer these questions, or to post some historical research they had undertaken. They are an absolute mine of folklore, history, archaeology, gossip, rumour, and all round fascinating stuff, and the Cheshire version is published online by the archive.org project – you can read it by following the link above (alas, the ‘Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire’ volumes have not yet been digitised). Here’s what was printed:

30th March 1889

About fifty years ago I recollect seeing a tablet in the wall, about twenty yards from the bridge, on the Derbyshire side, with the words Matlock’s Leap, and I think the date was upon it. I recollect being told at the time that it had been placed there by the landlord, Mr James Boulton, who, at that time kept the Norfolk Arms Inn, to commemorate a miraculous escape that a man named Matlock had one dark night. This man was in the Norfolk Arms, and he was suspected of having committed some depredation, and he was told the constable was at hand, when he immediately ran out of the house, ran across the road, and jumped over the wall down into the river, which I should think is here about forty feet perpendicular. I was told the man was not hurt. His friends got a ladder and got him up again all right. I have noticed that the tablet referred to has been removed from the wall where it was fixed. I shall be glad if any of your readers can tell me why and where it has gone.

Ashton-under-Lyne. I. W. B.

Now this was interesting.

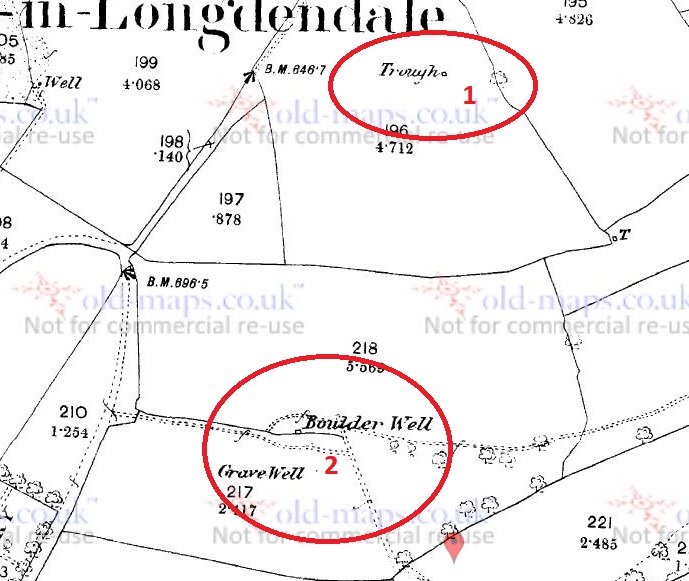

Firstly, Matlock’s Leap was a thing… which is a relief. So Matlock was a person, and the leap was one over a wall and 40ft into the river Goyt… and he lived. Blimey! But also here is a wealth of detail. The tablet commemorating the event had evidently disappeared by 1889, but at least we know where it was – about here, to be exact:

I looked, and could see no sign of where the stone would have been fixed, and looking along, it seems to me that the whole of the wall has been replaced at some stage post-1832 – it looks Victorian, rather than Georgian, and it may have been then that the stone was removed.

Presumably, given the Norfolk Arms was the location of the leap, and that the landlord had put the tablet up, the pub was also the location of the slap up meal mentioned by George Booth. I was also intrigued by the ‘depredation‘ of which Matlock was accused.

DEPREDATION. noun. The act or an instance of plundering; robbery; pillage

That’s an oddly specific word… what did he do?

Two weeks after the above query was published, a comprehensive answer was given, one which reveals the whole story – it’s easier to reproduce the whole thing:

13th April 1889

MATLOCK’S LEAP.

In reply to your correspondent who asks about Matlock’s Leap, I may say that I do not profess to give anything I know personally, but I recently accidentally met a friend who lived at Marple when a youth, now he is over 70 years of age, and he told me a few matters he remembers about it. His first recollection of Matlock was before the “leap” had taken place, but he had often heard of “burkers,” “body snatchers,” and “resurrection men,” and was no little alarmed when he was told that these men stole dead bodies from churchyards for the doctors, and that the doctors made physic out of them which caused physic to taste “so bad.” One day, quite 60 years ago, my friend went to the Horse Shoe Inn for his father, who was indulging rather unduly to the neglect of his business. When he got there he found his parent in conversation with a man, and the father wishing to let the lad know who he was, contrived to whisper to him, and said, “that is Matlock; he is a burker, fetches dead people out of church yards at nights.” This was so strongly impressed on his youthful mind that he remembers it yet quite distinctly.

With regard to the stone that formerly marked the place of Matlock’s leap, my friend informed me that a present alderman of Stockport told him on one day that he last saw it in Compstall Gardens when they were kept by Mr Calab Warhurst.

The wide-awake “burker” had received a commission from a local practitioner, who, to tell the truth, was a most successful doctor, to supply him with a subject to operate on. And one night when the doctor was very busy in his surgery with patients, in walked Matlock with a bag on his back. The wily doctor did not wish to enter into any conversation or explanation with the “burker,” or seem negligent with his patients by leaving them to attend to him, so he simply gave him a well understood motion to go on through the surgery, which he did, and shortly returned, the doctor giving him five shillings, with which instalment he left the place. But, lo! when the doctor went to examine his bargain, he found that his hitherto trusty agent had hoaxed him, for instead of a corpse the bag was filled with lumber. So much my informant can vouch for, to which rumour adds – and, with a knowing nod, my friend says it was so – that the doctor was not only very clever in his medical profession, but also of much more robust build, and more capable of self-defence than was his tricky agent; and that when he next met with the ”burker” he give him a sufficient fisticuff chastisement. After this reconciliation and better understanding was entered into between then, and their friendship and business engagements were resumed from time to time as it suited their various purposes.

A short account that I have had from another source about the immediate cause of the leap, may be of interest to some of your readers. On the day I read your last issue and saw the account of Matlock’s leap, I met with a person who resides not far from the place, so, in a jocular manner, I said to him, “Do you know anything about Matlock’s leap and the resurrectioning case?” He replied “Yes,” and added, “and you will be surprised when I tell you whose body it was. Then he told me that the grave had been watched fop seven nights for fear that some one should come and snatch a body which he said was that of a large stout man that had been buried in Mellor Churchyard, in the year 1831, and after watching the grave for so long, the family and friends thought there would not then be any attempt made to take the body, but on the eight night it was ‘snatched’ or taken away, and a week after the coffin was found in a lime hole in the neighbourhood” and, he continued, “I have a cousin now living at Hazel Grove who was one of the watchers, and the body was that of my father.” The informant was only six weeks old when this occurred, so of course only knows what he has been told, perhaps chiefly by his own family.

I will conclude with a short account of the leap as it has been told to me by my elder informant who was living on the spot at the time. One night a number of men of the village were at the Norfolk Arms, and were bent on having a lark. It had been agreed that there should be a tap-room trial of Matlock for the ” snatching ” of this body. A judge was appointed, a jury was empanneled, and Matlock was on his trial; when matters were at their height, one, Dick (Richard) Middleton, a plumber and glazier, went into the room and said to Matlock “the constable is after you d_____l “. Now, just what was expected, happened. Matlock was startled, and rushed out of the house; it had been planned that a number of men should be outside – on the right side of the house, and a like number on the left side – so that whichever way he went they were to pretend to try and catch him. He first ran up the bridge and was met, and a scuffle took place, from which he was permitted to escape, and ran to try the other way; here again he was met by another gang and again there was a scuffle, without any serious attempt to secure him, for that, too early accomplished, would have spoiled their sport ; but he saw the two crowds meeting together, and himself hemmed in between them and in such close quarters, and having only time to think of the judge and jury in the house, the crowd on the right hand and the crowd on the left, in a sort of despair, he took the terrible leap into the river, as stated by your correspondent. This is correct in the main. If any little error of detail is seen by anyone who may be better informed, perhaps they will be kind enough to correct it.

H.H. Stockport.

Well, there we have the full story… Matlock was a bodysnatcher. Blimey!

Prior to 1832 only the bodies of people executed could be cut up and examined anatomically, it was actually a part of their punishment. There was, then, a serious shortage of cadavers with which to teach anatomy, which in turn meant that doctors, and in particular surgeons, often had little experience in the reality of the human body and how it worked. In order to address this, an illegal trade in corpses was started, in which criminals – ‘resurrectionists’ – dug up the newly buried, and removed them to be sold to doctors, surgeons, and medical schools. Seemingly few questions were asked, and from a rational and medical perspective, this made sense – the dead are dead, but they can in turn help the living. Ethically and morally, however, the trade left a little to be desired, and the public at large, as well as grieving widows and parents in particular, were outraged. As the ‘trade’ reached fever pitch in the 1820’s and 30’s, watch groups were set up to keep a watch over newly buried bodies to ensure they got their eternal rest.

Matlock must have been connected to a certain Captain Seller and his gang of ressurectionists based in Cocker Hill, Stalybridge; their fascinating story is told on the Cocker Hill website here and in this Facebook post here (well worth a read). It seems the gang were active in the Hollingworth area as well, so Marple and Mellor are but a cart ride away. Bodies were dug up by the gang and spirited away to Stalybridge, where they were transported via canal to Manchester. However, the Peak Forest Canal actually passes through Marple Bridge on the Cheshire side, so the journey from Mellor church (mentioned in H. H.‘s answer above) would be easier to make.

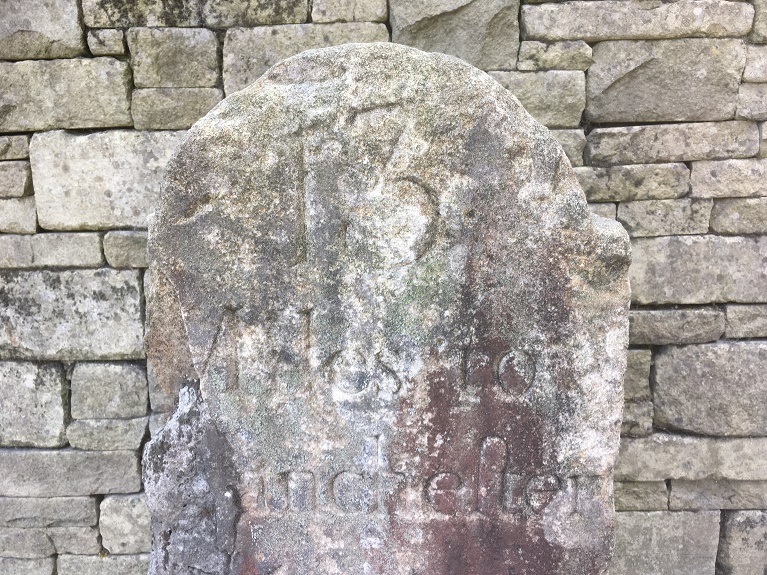

Might we suggest, then, that he was also connected to the taking of bodies from Mottram Church? Famously the churchyard of Mottram St. Michael and All Angels is the home of the empty grave of 15 year old Lewis Brierley, whose corpse was stolen in 1827. His grieving father displayed the empty coffin at the Crown Pole at Mottram, opposite what was once the White Hart pub (now being converted to houses), giving the eulogy that was later inscribed on the gravestone above the empty grave:

Tho’ once beneath the ground his corpse was laid

For use of surgeons it was thence convey’d.

Vain was the scheme to hide the impious theft

The body taken, shroud and coffin left.

Ye wretches who pursue this barb’rous trade

Your corpses in turn may be convey’d

Like his to some unfeeling surgeons room

Nor can they justly meet a better doom.

In memory of Lewis, son of James and Mary Brierley of Valley Mill, who died October 3rd 1827 in the 15th year of his age

The father apparently kept the coffin and was eventually himself buried in it. The gravestone, complete with inscription, is to be found to the north of the church.

The proximity of Mottram to Stalybridge, and the fact that it is unlikely that there was more than one group active in the area, suggests strongly that Matlock was indeed connected. I’d like to return to this subject at some stage in the future, as I find it fascinating, if a little grim.

In 1832 parliament passed the Anatomy Act, which effectively ended the trade by allowing any unclaimed body to be anatomised, and from then on poorhouses in particular supplied the surgeons with their dissection corpses in great numbers.

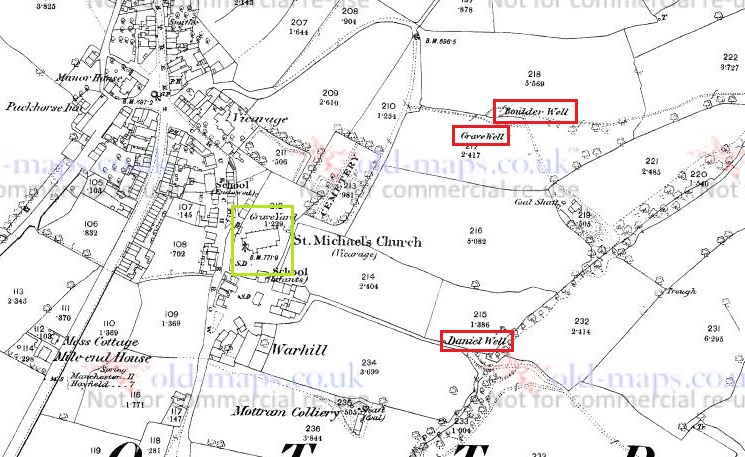

So where is the stone now? The above letter by ‘H.H.’ of Stockport suggests it was last seen in Compstall Gardens sometime prior to 1889 (when they were kept by a Calab Warhurst). I presume that this refers to the pub once known as The Compstall Gardens Inn and the “private recreation and dancing grounds” that were attached to the pub – here, for example. These are still attached to the pub, which is now known as The Spring Gardens, and are shown here on the 1898 OS map.

And here the matter must rest, alas… the trail went cold. I emailed the Spring Gardens asking if they had any information about the stone’s whereabouts, but sadly to date I have not heard anything back. I will pop in for a pint (or two) when lockdown ends and make an enquiries then, but I am not holding out hope. Even the wonderful Marple Local History Society people had no information about it (my thanks to Hilary Atkinson for her help). It was most likely lost or made into part of a patio, which is a shame as this little slice of history is no longer widely known about.

So there we have it, a tale of improbable escapes and graverobbing. If I find anything more about the stone or the graverobbing, I’ll let you all know. In the meantime, stay safe and look after yourselves and each other, and until then I remain,

Your humble servant,

RH