Some years ago, whilst walking to the station for my daily commute, I passed down King Street in Whitfield. As I approached the middle of the street, I had to skirt around some scaffolding that was placed onto the front of a house, and projecting into the path. As I passed, I looked down and saw, scattered quite literally all over the the path, dozens of pieces of thin green metal. On closer inspection, I could see they were copper nails, and promptly pocketed all that I could see.

The roof of one of the stone-built terraces on that street was being replaced and the copper nails were the fall out, having been removed during renovations. They had been used to pin the heavy stone roof tiles in place, each one carefully nailed into the timber through a hole drilled through the stone tiles, and now, no longer needed, they were simply tossed aside onto the street to be swept up. Now that is, I think you’ll agree, a shame; these little pieces of history deserve better! And besides, I can’t resist picking up interesting, and sometimes shiny, things!

They are formed from copper, rather than iron, because copper doesn’t decay the same way iron does – it maintains its strength for far longer, resisting the elements and doesn’t turn to rust. Ship’s nails are made from copper for the same reason. Instead, it develops a thin green patina called verdigris, which makes them particularly beautiful to look at, especially when the verdigris is partly sanded off.

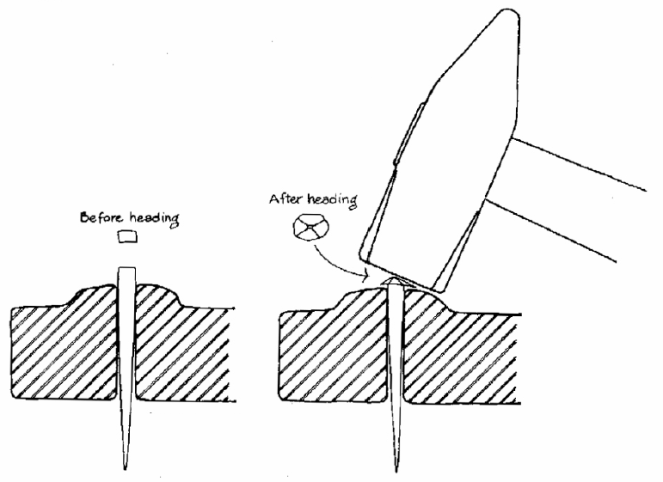

They are also hand made – each one cut via a press from a long flattened strip of copper, which accounts for the square body of the nail. It is then placed into a small mold or former, point down, and the exposed top is hammered by hand until it flattens out, forming the nail head, like this:

This method accounts for the thin flattened strips on opposite sides of the nail, just below the head – the former is made of two adjustable halves to enable different size nails to be made, and when pressure is applied via the hammer, the copper is forced into the gap between the two halves of the former.

These nails date from the early to mid-19th century – I seem to remember reading somewhere that the houses in King Street were built in the 1860’s, and, one assumes, the nails are contemporary.

That said, my own house, which dates from the late 1840’s, originally had wooden oak pegs holding on the roof stones. When we replaced the loft insulation, we found dozens of them lying on the floor of the loft where they had been thrown down.

What I love about these is that you can see each the stroke of the knife that was used to form the pegs – in the photograph above the peg at the top was made using eight strokes, the middle using seven strokes, and the bottom peg using eight.

Whilst being fun and interesting artefacts in themselves, there is a sense of connection with the human in these objects; both have been formed by hand, and the mark of that hand is visible in both – the hammer and the knife. That for me is what makes archaeology so fascinating, connecting to past people through the objects they made and used, and the story they tell us.

Update.

Whilst taking advantage of the sunshine to do a little gardening, I came across this little piece amidst the great piles of stone that originally littered our garden – a stone roof tile. It is very small, and is presumably a broken fragment, which explains why it is no longer on our roof. What is fantastic about this is the fact that you can see the hole that would have originally taken one of the pegs illustrated above. I love things like that!