What ho! Greetings one and all. Come on in and take a seat. Can I get anyone a drink?

Today, I finally finish a blog post that was started 2 years ago. Not for any particular reason, it’s just that some posts are more urgent, and others seem to, well, ferment… if that’s the word I’m searching for. If it isn’t, it’ll have to do.

So, I was reading a little bit about the history of St James’ church, the parish church of Whitfield. And a splendid one it is too. Living in Whitfield, I have a strong attachment to the church, not least of which I can see its spire from my bedroom window, but also Mrs Hamnett and I were married there. And by a spooky coincidence my namesake and pseudonym – the original Robert Hamnett – was a member of the congregation and is in fact buried in the graveyard there, something I didn’t know at the time of my nuptials.

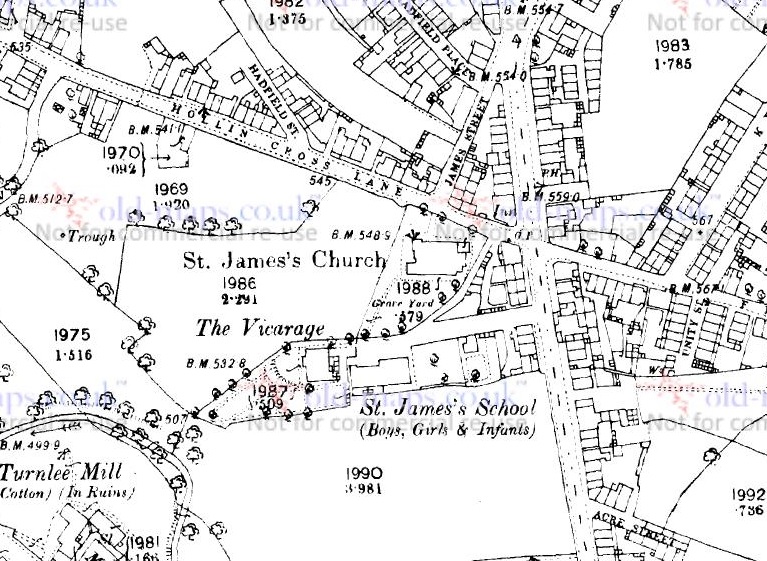

The church was built in 1845 (and consecrated in 1846), on land that was bought from the estate of Thomas Dearnley, of Tintwistle, a schoolmaster who had died in 1842, at a price of £110. This land – Lower Meadow as it was originally called – was described in the deeds as being bounded by “Holly Cross Lane and Wall Sitch“. Holly Cross Lane – now known as Hollin Cross Lane – makes sense, but Wall Sitch? Well, it is an unusual name, and, given my love of placenames and their meanings, I went digging. According to the paper “Semantic Structure of Lexical Fields” by David Kronenfeld and Gabriella Rundblad (2003:29) (no, I don’t understand what it means either… something to do with words, apparently) Sitch is “commonly used for (very) small streams, especially those flowing through flatland, and can be used for both natural and artificial watercourses”. It is derived from the Old Norse ‘Sik’, via Old English ‘Sic’, both meaning a marsh and/or a watercourse. It is not uncommon in the North West, and in particular those areas that fell under Dane Law (that is the area controlled by the Vikings, and subject to their laws). Glossopdale and surrounds is right on the border between Anglo-Saxon Mercia and Viking controlled Danelaw, so it is not surprising that we have a few Norse place names. Indeed, a little further up the valley, off Monk’s Road, is a ‘Sitch Farm’, which sits just above a small brook.

So then, I went looking for the Wall Sitch – the small watercourse by the wall – and do you know what? I think I found it, despite it being very hidden.

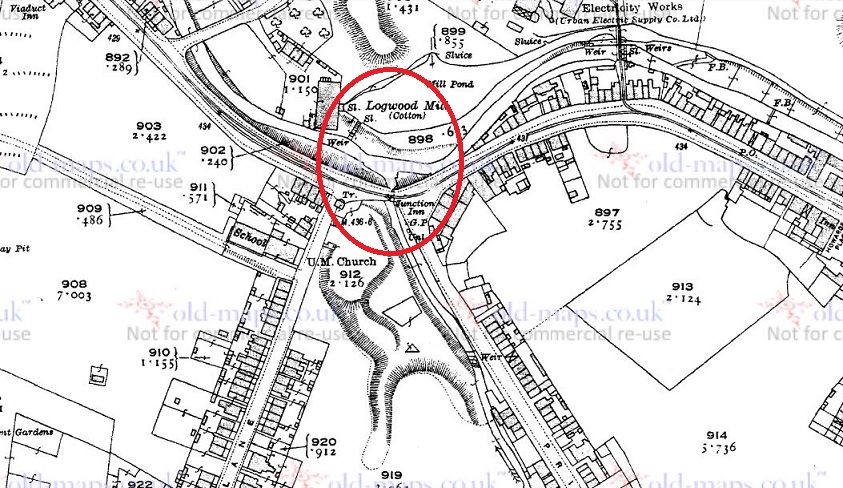

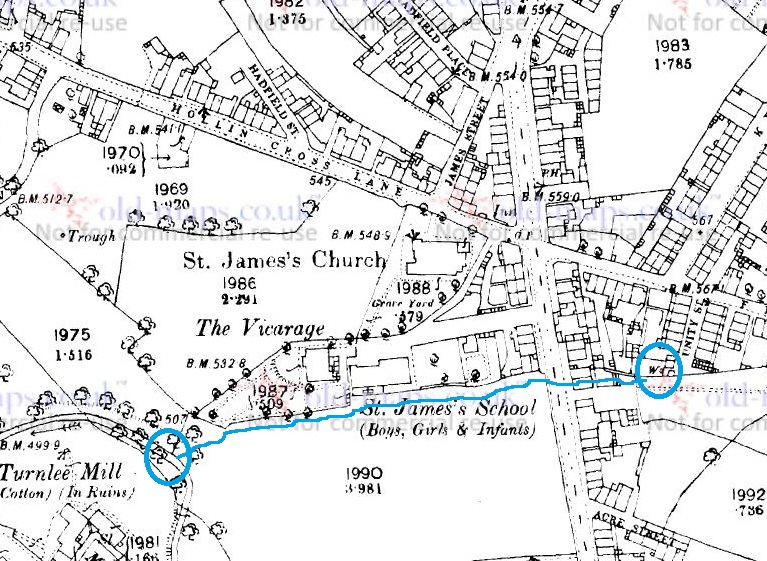

Here’s a map of the area, so we can see what’s what.

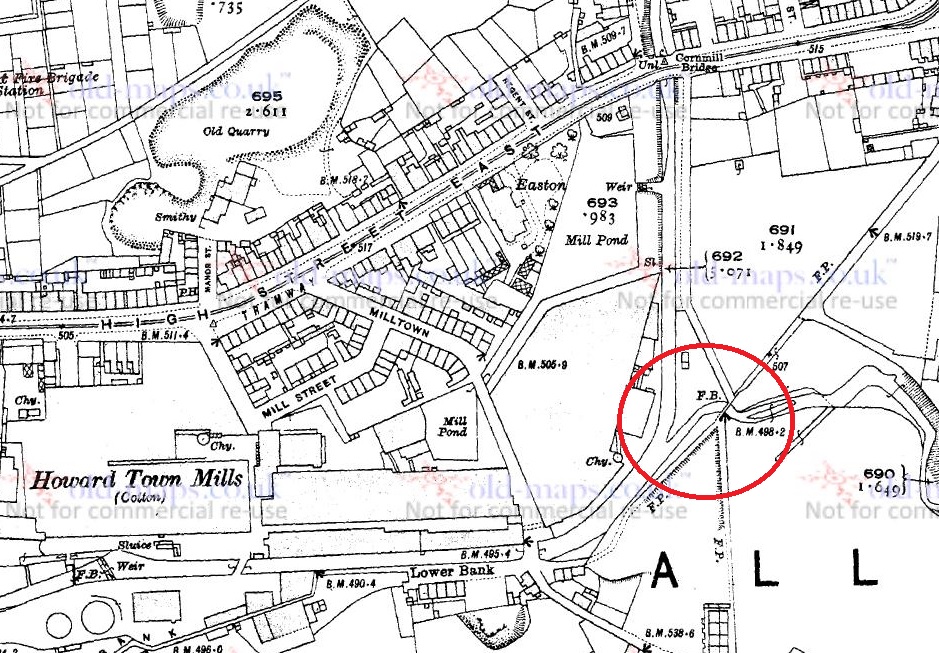

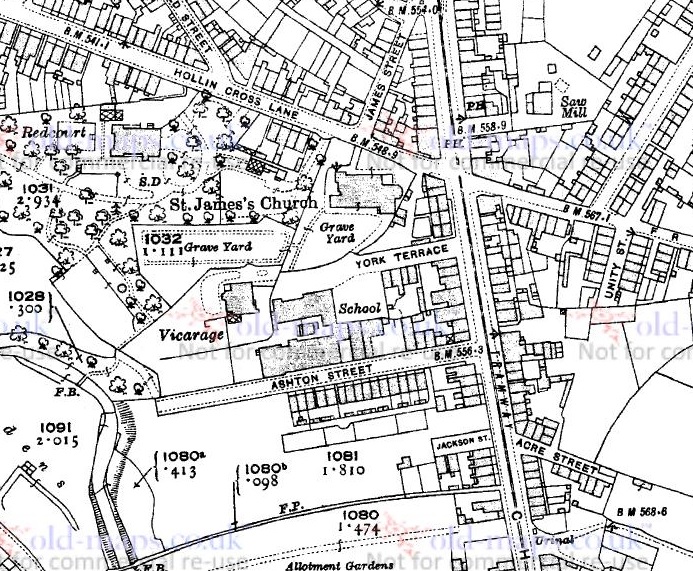

I first thought it might be roughly parallel to Hollin Cross Lane, so I looked at the south side of the churchyard. Nope… nothing on the ground, or on the maps. “But wait… hang on a moment!” thought I. The vicarage and St James’ school (the original one, not the newer one further up Pikes Lane) must have been built on church land too, and at the same time as the church, so I looked at the boundary below them. Well, it is immediately obvious there is no stream visible as such, but there is something very odd about the shape of the boundary – you can see it in the map above above the words ‘St James’s School’. Generally, when someone draws a boundary, it is straight, unless of course something stops it from being straight… and this one is a meandering shape. This type of ‘landscape archaeology’ can really help in identifying older or lost features, and I think it does here – the boundary has been determined by the course of the stream. So I went looking down Ashton Street (a road not yet built in 1880) to see what, if anything, I could see. Here it is on the 1921 map:

And here it is in real life:

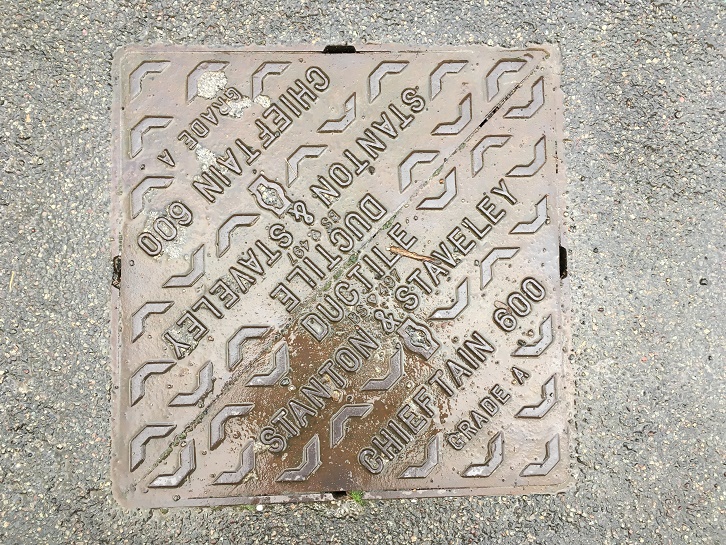

Well, disappointingly, there was not a lot to see. The school has been demolished – Master Hamnett now attends the successor school, built in the early 1920’s – and houses now occupy the site, although there are traces here and there. However, halfway down I heard a noise. Water! Below a drain cover in the road water was rushing, and then again farther down the hill toward the Long Clough Brook, below another drain cover.

This has to be it. I wondered if there was an outfall into the brook, surely the final destination for the sitch? And lo!

Excellent! I love detective work, and it’s exciting when a hunch pays off. This is exactly the sort of thing that I started the blog for. So there is the outfall, but it got me thinking… where is the start of Wall Sitch? Well, tracing the meandering line of the sitch back, and under Charlestown Road, it seems to stem from a well (marked with a ‘W‘ on the map below) at the end of Unity Street. Now, by coincidence this well was the subject of a previous blog post – check it out here – and although it is no longer there, clearly the water from what would have been a spring head, similar to Whitfield Well and many others in the area, is still running.

Makes you wonder what else is lurking, hidden in the ground, or in maps.

That’s all for now, but more soon – I have some posts that are 3/4 finished, so I should be able to get these published fairly rapidly. So, until next time, and as we head into another lockdown, take care of yourselves and each other.

I remain, your humble servant,

RH.