So, apologies for the late running of this blog post. I have half a dozen half-written posts at any one time, and this one seems to have had a difficult birth! It was finally scrawled on the back of the minutes of the AGM for the Glossop & Longdendale Archaeological Society in a cafe whilst waiting for Mrs Hamnett to come out of surgery in Wythenshaw Hospital! (All is good on that front, and she is making a recovery). Apologies also for the length of this one, and for the archaeological theory. I do love a good bit of interpretation, and in my previous archaeological life this was the stuff that nourished!

I was having a conversation with my brother-in-law the other day (Hi Chris), and he asked whether I had seen the standing stone on Long Lane, between Charlesworth and Broadbottom Bridge. As it happens, I had, and it was on my ‘to do’ blog list.

And here it is, being done… well, we’ll get to it in a minute

Standing stones and stone circles are some of the things that first grabbed me when I began to look at archaeology seriously. The fact that they were a tangible and impressive representation of the past made them stand out, and yet they were enigmatic – their function and meaning still not fully understood. Single standing stones in particular have been overlooked as monuments; their very nature – a single stone, standing upright – has meant interpretation is difficult. Moreover, they are largely undatable unless associated with other monuments such a stone circle, and people throughout history have stood stones upright, and for a variety of reasons (cattle scratching post, waymarker, gatepost, etc.). Generally, though, they are considered to belong to the later Neolithic and Early Bronze Age (roughly 3000BC – 2000BC). As to their function, they are often viewed as marking a territory, or as a meeting place, usually with ‘ritual’ overtones. In more recent times, they are often associated with folklore and the supernatural, and even leylines.

Recent archaeological work has begun to unpick the possible meanings and functions of many of the monuments of prehistoric Britain, and especially those of the Neolithic. This has been done more subtly and intuitively than previously, and looks at monuments in their surroundings, and how the people would have experienced, used, and passed through them, rather than viewing them as just objects. Words like landscape and phenomenology are used, and it often draws on other disciplines such as philosophy to help with understanding the past. Extrapolating from this work at the larger monuments, and in particular the pits, causewayed enclosures, and chambered tombs of the Early Neolithic, we can use some of these ideas to explore a possible meaning of the standing stones of the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age.

As I’ve said before, a standing stone is just that, a stone, standing. But conceptually, it is much more than that, it is a fixed point in the landscape, around which human experience can revolve, and emerges from a concern with marking a particular space as being different from it surroundings, transforming it, and placing it within the landscape but apart.

It is clear that the actual creation of monuments such as these was just as important as the finished product, and the erection of a standing stone is not a simple task. It requires group work and cooperation; with the stone weighing perhaps a ton or more, families, extended families, kinship groups, or even clans would be working together to make the stone. It would be a period of community, sharing work and food, and the creation of joint place. The stone would have to be shifted and shaped, and here we have decision to be made. From where is the stone to be quarried? The source may be significant to the people creating the monument, and perhaps that quarry or stone type already figures in their stories and beliefs, already a sacred site. Although practical considerations are possible, it may not always be the case – the Stonehenge Bluestones were moved by land, sea, river, and land from the Preseli Hills in Wales – a journey of over 150 miles, because they were deemed important. Our practical concerns are different from theirs.

Then we must consider location, why was the stone sited where it was. The larger monuments, such as the enclosures of the Early Neolithic, often have evidence of earlier occupation, and it seems that the monuments are referencing these flint scatters and back-filled pits, a way of acknowledging those who went before – the ancestors. It may be the case with the standing stones. But equally, they may reference something else – a feature of the landscape, or perhaps some other, more numinous reason which we would never be able to fathom. Did a shaman have a vision suggesting the site? Or did lightning strike? Or someone die there? Or… you get the idea. And did the stones stand on a bare hillside as they do now, or did they lurk in a bright woodland clearing?

Once in place, the people responsible for erecting it might visit periodically – every year on midsummer’s eve, for example, or every full moon, or when the cattle are herded from lowland pasture to the upper areas, or even every day. But certainly through these periodic visits it would be seen as, calendar-like, marking time, or even creating a ‘mythic’ time, outside of ‘real’ time. They might have visited in large groups, taking the form of kin-related clan-wide celebrations, for example, or perhaps in small family groups, or even as individuals. Each visit would recall previous visits, previous times of coming together in celebration, or in mourning, for example. But there would be feasting and celebrating, certainly, with people gathered in their groups round hearths and fires.

Perhaps the area around the stone was kept spotlessly, meticulously, clean, and each visit revealed traces of the old hearths clearly, and the conversations, people, exchanges, jokes even, that happened around those hearths would be recalled and spoken about. And it’s not hard for us to imagine a group of people, framed by firelight, moving in a circular fashion around the stone, dancing. But perhaps, and I suspect more likely, the area around the stone was littered with the detritus of these older meetings – pottery, animal bone, flint, pits dug into the earth, stone, and other bits and pieces, all deliberately displayed as a reminder of the past visits. There may well have been human remains, too, in the form of cremation or as an internment, or even random bones, carefully kept and handled – curated for generations – before finally being deposited around the stone. Each item or object speaking to the people of the past, of past lives and events, and of the ancestors. With each visit, again and again, there was the creation of new memories, new meetings, and yet still the recollection of older ones – the ancestors would have loomed large and heavily in these times.

The stone here acts as a mnemonic device, an object that helps us remember. That is its purpose, its meaning… to help us recall previous visits to the stone. Using the stone as a focus in this way, time can be manipulated: the individual can visit past people and events, travelling and recalling; but equally the ancestors and past gatherings can be brought into the present through shared memory. Importantly, the ancestors can be projected forward into the future, asking for their intercession for a good harvest, for example, or for help and advice.

And of course, when the people gathered together for feasting and celebrating, there would have been exchanges in the form of gifts and barter – and from hearth to hearth, and valley to valley, there was an exchange of resources, news, gossip, alliances, ideas, beliefs, objects, allegiances, skills, animals, marriage partners, and so on.

In fact, all the drama of human existence revolving round this fixed point in the universe, a node, a single stone standing in not just a physical landscape, but in this case a cultural landscape, and on a personal level, a psychological landscape.

Phew!

So then, the stones…

- Hargate Hill Stone

Let’s start with the stone that sits on the corner of Hargate Hill Lane and High Lane, the road between Simmondley and Charlesworth. It’s here:

Here is the stone.

The stone is very obviously deliberately placed, and sits on the junction of two tracks, both clearly ancient, and like many standing stones, it stands mid-slope, i.e. not at the top or bottom of the hill. It could be argued that the stone is placed as a marker for the tracks, but I suspect that the track from Hargate Hill used an already existing stone as a sight marker. Interestingly, Neville Sharp suggests that its chisel-like head points towards Shire Hill, some 3km north west of the stone. And yes, seemingly it does.

This may be important. It is not uncommon for standing stones to reference features like this, and Shire Hill is fairly prominent in the landscape, even on gloomy days, it can be made out easily, as the above photograph shows. Interestingly, in the mid 1950’s, the cremated remains of a female dating to the Late Bronze Age was uncovered on the south slope of Shire Hill during the building of a bungalow there. The remains had been placed in an upturned burial vessel, which was laid on a bed of charcoal. Sadly, there is very little information available about this important find. Out of our period, but points to prehistoric activity on the site.

There is, marked on the 1887 OS map (see above) another stone just to the east of this one. I have looked but cannot find any remains of a stone, even a small one, and not even reused as part of a wall – whatever was there in 1887 is no longer there now, sadly. But it is worth mentioning that standing stones sometimes occur in pairs.

- Hague Stone.

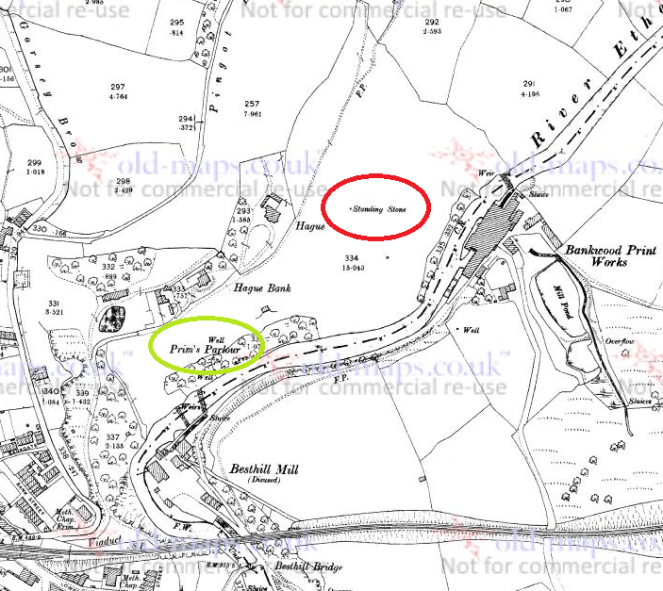

I found this one years ago – I did a ramble in search of this stone and Pymm’s Parlour Roman rock shelter on the banks of the River Etherow (the subject of a future blog). Finding it was not easy, as it now tucked away in a wooded area, and for some reason I didn’t take any decent photographs… not sure why.

Here’s the stone.

It’s a fairly hefty stone, as you can see, and tucked away, though the 1898 OS map shows it as standing in open fields. I will get a better photograph this winter, I promise! Not a great deal to say about this stone, though I think it is important, as we’ll see.

- Long Lane Stone

Very visible from Long Lane, this stone has long intrigued me.

I have been unable to get a decent photograph of the stone, as it stands in a field that grows turf for Lymefield Garden Centre, and one doesn’t like to trample on the new grass (and I don’t recommend you do either). Every other time I’ve tried, it’s been too dark, too bright, etc. So here is the Google maps version. I’ll keep trying, and replace when I can.

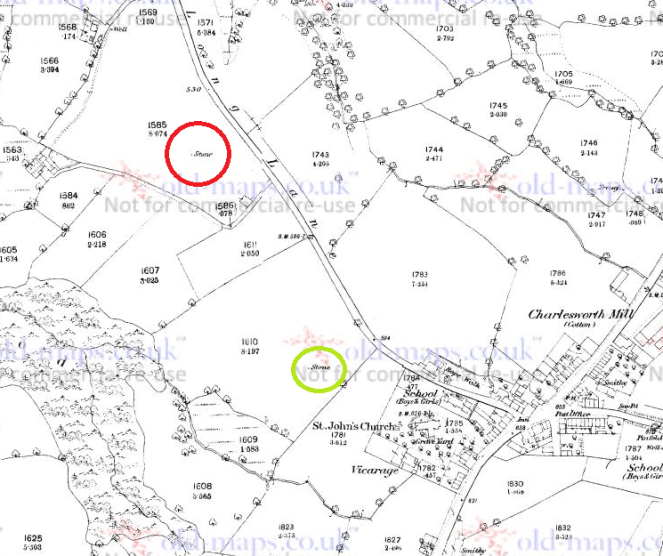

It’s a fairly bog-standard standing stone, shaped and set into the ground in the middle of a field. The 1898 OS map shows it standing at the head of what it describes as an ‘Old Quarry’, something that the earlier maps don’t show. I can’t believe it’s a quarry… what would they be quarrying here? A marl pit perhaps, but not a quarry. Perhaps it is a feature associated with the stone? What I do find interesting is that the stone hasn’t been moved – either in the past, or more recently, in order to make harvesting the turf more easy. Folkloric associations with bad luck? Whatever the reason, it’s great that it remains

As with the Hargate Hill stone, on the 1887 OS map, there is another stone marked, south of the main one, further up the hill toward the church (in green on the map). I have not been able to investigate this as it now stands on very private property, behind a locked and alarmed gate. I have not been able to see anything on later maps or aerial photographs, and it may just be a small unrelated stone – the early OS surveyors marked anything that couldn’t be moved on their maps. I would still like to investigate though, so if anyone knows anyone or anything, please let me know.

Now, these last two stones, for me, are particularly interesting. Let’s play a game of ‘what if’ Assuming that the stones existed at the same time, they would have been intervisible – you could see one from the other. They stand on opposite sides of the river, and on opposing hillsides, but are at about the same elevation, and both middle hill, not at the top. In a sense they are facing each other, and we may understand them perhaps as rivals, representing two different nodal points, perhaps for two different clans. But what if, instead, they are viewed as complementary? What if we take them together, as a pair, making a statement? The location of the Hague stone is at the head of the valley, just past the Besthill Bridge and the cliffs of Cat’s Tor there. The cliffs are steep and difficult, and logically the slope where the stone is located is the first patch of land that would allow it to be dug in. I feel almost certain that the stone references this point, and that it is placed at the head of the Longdendale Valley.

If we accept that the Long Lane stone references the Hague stone, then we seem to have a pair of distant, yet connected, stones standing at the head of the Longdendale Valley – gateposts of a sort allowing you access into the valley, and which form a part of a larger landscape, shaped and controlled by the people in prehistory. This puts a very different spin on the place, and suggests all sorts of areas for further research.

Of course, it is all ‘what ifs’ – a story if you will, and one that is completely unprovable. But it is possible, and I genuinely believe that the Hague stone at least is there for that purpose; you often find stone circles situated at the confluence or head of valleys, so why not a single (or pair of) stone(s)? Something to think about, if nothing else.

If you are interested in the ideas about British prehistory that I have been talking about, there are a number of very good books on this subject. I would recommend starting with:

- Britain BC by Francis Pryor An excellent and easily read overview of prehistoric Britain. Really very good.

- Stonehenge by Mike Parker Pearson A compelling & easily read account of the Stonehenge Riverside Project, and in particular it covers Parker Pearson’s theory that stone = death, and wood = life.

- Ancestral Geographies of the Neolithic by Mark Edmonds Academic, but a good and accessible read. Full of wonders. Highly recommended.

These next are academic archaeological books that are a bit more complicated, and require some background knowledge.

- Understanding the Neolithic by Julian Thomas Essential reading, but very dense. Not recommended for the casual reader.

- The Significance of Monuments by Richard Bradley. Another good one, dense in places

- Ritual and Domestic Life in Prehistoric Europe by Richard Bradley. Again, really good, and quite accessible. It covers the whole of Europe.

As always, any comments, questions or corrections are welcome, just drop me a line – either email in ‘contact’ above, or in the comments section below. Next time I’ll blog about some interesting pottery… I think.

Your humble servant,

RH

There’s an alternative explanation for the Hague and Long Lane stones – that they lie close to an ancient way. The shortest practicable walking and riding route from the East Midlands to East Lancashire runs through Charlesworth and Mottram, and there’s evidence of substantial traffic along it until the turnpikes created easier albeit more indirect routes, although there was a proposal in the 1790s to turnpike it more directly. Travellers going north until the 17th century, across mostly open country, would have come along the general line of Monks’ Road to the summit at Charlesworth Cross, then down the hill into the village, the still-visible band of ruts being at least 60 metres wide; then along the ridge now followed by Long Lane and Bankwood Gate to a ford across the Etherow, then to Mottram via Lower Mudd, there being a deep holloway where the way cuts through the ridge above Pingot Lane. In 1683, a bridge was built across the Etherow Gorge at Best Hill, and Long Lane and Littlemoor Road would have been constructed to connect with it, bypassing the ford.

Although the evidence we can see now is of this way towards the end of its life as a regional route, it’s reasonable to assume it had been in use for thousands of years, and the three stones all sit on the west side of it. It’s unlikely that they would have been needed as waymarkers in later eras, when the traffic coming down to the ford would have left very clear marks on the ground, but it’s possible to imagine that – perhaps in conjunction with other stones now lost – they might have served such a purpose when traffic was very light and seasonal and the land was completely wild and open. Although travellers tended to spread out and find their own line across open moorland, there might only be one safe fording point and markers might be placed to guide them towards it.

LikeLike