What ho! Hope you are enjoying the summer so far. A quick post today, but more very soon.

So, I know I promised you pottery this time, and I can tell you are wildly disappointed, but this is an interesting bit of history. Honestly. It really is. Don’t just look at the first picture and yawn… Philistines.

There are a number of places around Glossop that never fail to produce some bits and pieces – Lean Town, Harehills, etc. One such place is at the top of Whitfield Avenue. Never lots, but always a sherd or two, and this time a piece of lead. Window lead to be precise.

Lead is one of those substances that is instantly recognisable once you know what it looks like, and can be spotted from quite a distance. It doesn’t rust, or even really react beyond producing a white powder on the surface. It is soft, which means it can get damaged – in particular bent – easily, but it also means that it doesn’t break in the way that pottery or glass does, so it often survives. It is also worth remembering that it is highly toxic, so be careful when you handle it.

So there it was, lying on the surface of the soil, a dull grey flash exposed after all the rain we have recently suffered. I would have picked it up anyway – I try and do that with lead, as it’s not great in the environment – but I knew at a glance what it was, and was excited as they can be interesting. I was not disappointed.

Window lead, or came as it is more properly known, has been with us for as long as there have been glass windows, and is essentially an elegant solution to a big problem – the fact that it is very difficult and expensive to produce glass in any large size. It is far easier to join together smaller pieces, and this was still the case until the 19th century, and why even early 20th century windows are made up smaller pieces separated by wooden mullions. But the multi-part aspect also allowed works of art to be created in the form of stained glass windows that adorned medieval churches and cathedrals, and is a fashion that continues down to today.

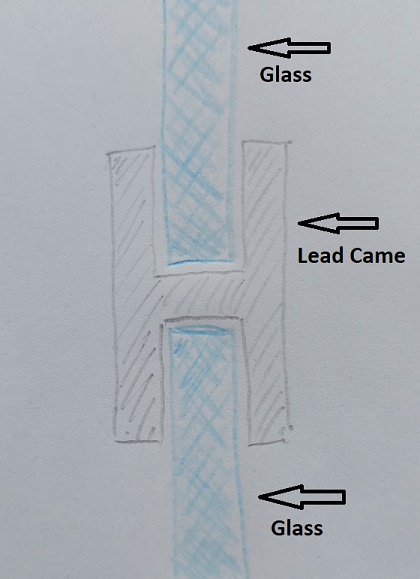

The came works by allowing separate pieces of glass to slot into its grooves, joining them together, with the whole being held in place by the window frame. In profile (that is, cut in half), came is broadly ‘H’ shaped:

So then, what can we say about this little piece of twisted metal? Well, a surprising amount, to be honest. Firstly, rather than being poured and shaped in a mould, the came has been milled – the lead was drawn through a former by a cog. This means that it is not medieval, but instead puts it into the archaeological ‘misc.’ tray that is ‘Post-Medieval‘ (roughly, after 1500). We can, however, narrow it down a bit; the cog used in the manufacturing process leaves characteristic tooth marks on the interior. As the process was refined and improved over time, these marks grew further apart, and broadly speaking, the closer the teeth, the earlier the date. On our piece of came, they are very close together, and thus an earlier date is suggested.

This is backed up by the slightly rounded profile, which is also associated with earlier examples. We might suggest a date of perhaps 1700 – 1800, possibly earlier, but unlikely to be later.

It seems to have been cut cleanly at either end, which means it is the original length, which is significant. It measures just under 6cm, or 2 1/4 inches, so not very long, but a perfect size for the diamond style windows that were common in the 17th and 18th centuries, when whole windows were made up of smaller pieces and joined by the came. Look closely, you can see the tin solder that would have joined it to another lead came piece.

Looking even more closely, you can see the putty that would have weather-proofed it still inside the groove.

Here is a 17th century window:

And here is our piece of lead in a mocked up window, showing how it would have been used.

How this piece of lead came came to be lurking in the soil on that rainy day is not certain, but it is in the right place – some of the oldest houses in Whitfield are right there, including Hob Hill Cottage with its datestone of 1638. The came must have originated in one of these houses, and at some stage either window was repaired, or replaced entirely. Indeed, if we look closely, we can see two marks where the lead flange has been lifted away from the glass to remove it.

At that point, the lead has been lost or thrown away. I’d love to be able to say for certain which house it came from, and the obvious choice would be Hob Hill Cottage as it is just opposite the find spot, but in reality who knows? I am amazed at how much information it is possible to glean from what is, at first glance, just a small piece of twisted metal. And see, I told you it would be interesting.

More soon. As always, look after yourselves and each other, and until next time, I remain.

Your humble servant,

RH

One thought on “Summer Came… and Went”