What ho, wonderful folk! Apologies for not publishing something sooner than today… truthfully, I have been a little overwhelmed and burnt out. Recent events have caught up with me, and I’m tired and somewhat sore; nothing a breather couldn’t fix, but sometimes it all becomes a little too much – please do listen to your bodies and minds, as they will often steer you on a correct course. Anyhoo, I’m back, and happy to be so. So here we are, with a long overdue post.

Last March, I went on a little Wander with a friend and family (hello GW). We had set off to do the first Where/When Wander, but having kids with us, we ended up playing around in the land by the allotments and behind Dinting Station. Aside from the fact that the area is interesting from a historical perspective (being connected with Dinting Station, and filled with old bits and pieces), it was also the location of the old Dinting Railway Centre/Museum. I vaguely remember visiting the museum several times as a child, and I recently bought a vintage guidebook on Ebay to try and fully remember what it was I went to.

The centre finally closed in 1990, and whilst all the trains and exhibition pieces moved elsewhere, the infrastructure – rails, and platforms, and buildings – all remains (here is a good article about the museum’s rise and fall, and there’s loads about it on the internet). Central in this wasteland – or forest of Silver Birch – the Engine Shed still stands, alone, derelict, and graffiti covered.

Anyway, comparing the photographs of then with now is really quite interesting, and shows just how quickly nature retakes land back, even heavily used and industrialised land such as this. Give it another 100 years, and there will be very little recognisable, 500 years and it’ll need an archaeological excavation to make any sense of the site; understanding site formation processes like this is vital as an archaeologist, and our case study is right here.

But today’s article is less about the centre, and more about a single aspect of the site. As generally happens, when a building is left derelict and unused, it slowly breaks down, and this is the case with Dinting station’s southern waiting room. Built in 1884, when the original 1848 station was rebuilt, you can see it from the train behind a fence; overgrown, derelict, absolutely terrifying. However, I didn’t know you could access the station from the back, via the patch of ground we were exploring. Well, I mean to say… one cannot simply say no when such gifts are presented to one! I had a brief explore! Brief because: a) I was probably trespassing, although it is very unclear to be honest (and I was by no means the only person there that day… or even that hour!), and b) we had children with us, and the place is phenomenally dangerous, with broken glass, falling masonry, and Jove knows what else. It was also going dark, and, I’m not going to lie to you, the place is spooky! Before we go on, I am also going to insert a cautionary statement here: I absolutely do not endorse you going to the place to look, and in fact recommend you don’t. So I took a very few, mostly terrible, photographs, and scarpered.

So I had a quick look around, as you do, and in doing so, I noticed that the whole roof of the exterior platform area had collapsed, seemingly as one, and the floor was littered with rotting wooden roofing and broken slates. And then I saw it… a single slate seemed to have survived intact-ish. I pulled it up and thought… I say, here’s a nice little blog entry! And so here we are:

Amazingly, it had both copper nails still in-situ, and whilst it has broken a little at the top, it allows us to see how it was made.

Geologically, slate is dense, and was laid down in thin layers, which allows us to quarry it and split it into relatively thin sheets using a hammer and chisel. It is further shaped using a soft hammer whilst over hanging a hard edge (or later using a machine, although still hand held). There is a fascinating YouTube video here that shows the whole process, for those who like to know… it makes it look so easy! This gives it the characteristic nibbled edges.

The different areas of dark colouring on the slate itself is the result of differential exposure to smoky polluted air, with the bluer/greyer bits being protected by wood or other slates.

The holes to take the nails were made probably with a metal punch – a single blow delivered from a hammer on one side, and the force of the strike spread and created a characteristic ‘exit wound’, much wider than the entry.

Looking at the nails themselves, they are fairly standard mid/late Victorian copper nails, hand finished, and square in section.

These wonderful things seem to be attracted to me, and I find them all over Glossop, or maybe it’s just I’m always looking down (I’m going to be Richard III-like before I’m 60 at this rate). And, as I can never resist them when I find them, I have quite a few, here in CG towers. I say “quite a few” like it’s 10 or 12. I actually have hundreds of the buggers, hiding in labelled bags, naturally, and hidden in drawers, but shhhhhh… don’t tell Mrs CG, this sort of thing makes her twitch. I wrote a little about how they are made, here, in this article, 8 years ago… man, do I feel old!

What a difference Welsh roof slates would have made to housebuilding. As I type this, I sit under a roof made from locally sourced gritstone (I think I can see the quarry from my house); each roof tile is an inch thick, solid stone, and I bet the whole roof must weigh somewhere in the region of 5 tonnes, with each individual tile moved up and positioned by hand. I watched them do it when my roof was re-laid, and it took a long time. Now think of the slate; each tile weighs a tenth of the stone one, meaning more could be carried up and laid quicker, it costs less per tile, and overall does the same job, but at a fraction of the weight of the roof, meaning smaller beams could be used. It’s no wonder that Welsh slate tiles took over almost immediately, ironically being brought here – safely and quickly – by the train. In fact, you can use the presence or absence of a slate roof as a quick and easy way of dating the buildings here in Glossop: stone roof, built pre-1850(ish), slate roof, post 1850(ish)

So there you go. Right, I have another article almost finished, and I’ll try to get it out to you before New Year, but I’m not going to make any promises! Just know that I’m always trying, but sometimes life gets in the way of this, what I want to actually be doing with my time!

Before I pop off, the new Where/When is now available – woohoo! #8 – The Bullsheaf Shuffle.

This edition is a great one! Two smaller Wanders to tickle your festive season.

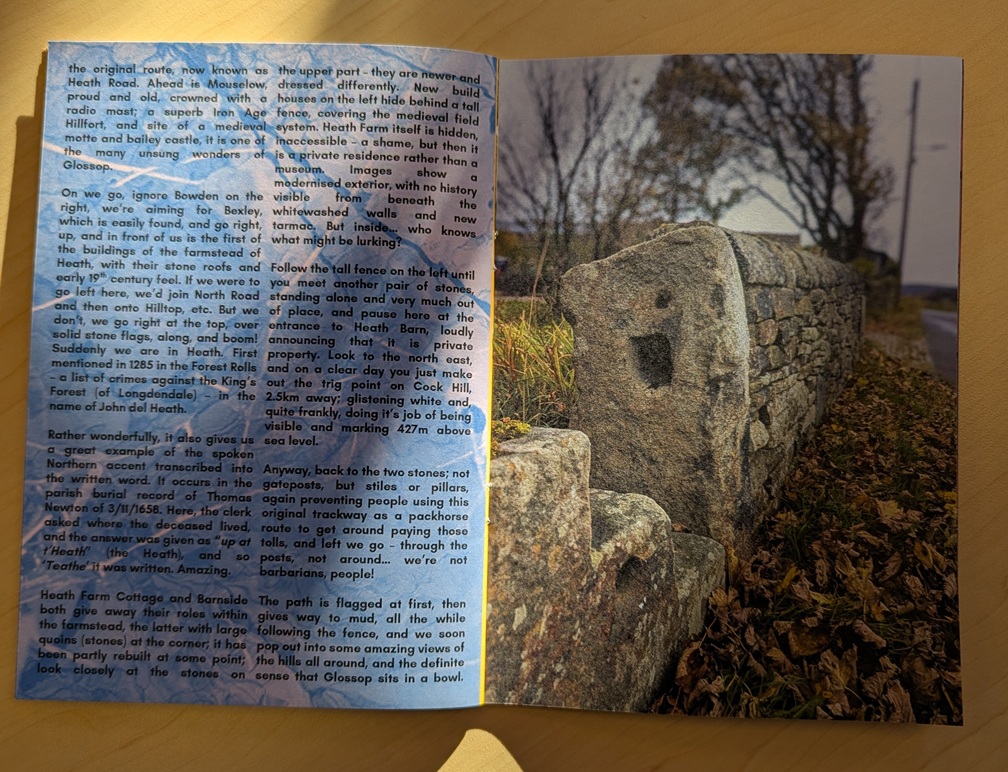

Two Wanders, both starting and finishing at a pub in Old Glossop, and neither very long, but all filled with history – medieval field systems, prehistoric remains, Ordnance Survey benchmarks, Roman roads (or not!), post-medieval trackways, Georgian buildings, a Victorian rifle range, and bits of pottery! A perfect stocking filler, available from here, or from Dark Peak Books, in High Street West, Glossop. All back issues are also in stock again, too, so knock yourself and grab a couple!

Right then, I’m off. Lots to do, annoyingly – the Christmas season is so wonderful, but equally is a real faff! As is work… and real life. However, until we next meet, please do look after yourselves and each other – you are all very important, even if you don’t know how, and to whom.

And I remain, your humble servant.

TCG

I remember the museum vividly—I’m fairly sure I still have my signed photo of the Blue Peter presenters from that era, alongside the Peppercorn Class A2 locomotive of the same name. It’s always a shame to see buildings deteriorate like this, especially when a properly maintained, watertight structure should stand for decades. In cases like this, the decline usually begins when the lead is stripped from the roof, followed by slates being removed. Once the windows are smashed, it’s sadly just a matter of time before the whole building falls into ruin.

LikeLike

Shall we discuss writing a paper about two culture zones in the Dark Ages Peak District? Here’s my map of surviving Celtic place-names: a very non-random distribution?

LikeLiked by 1 person