What ho, what ho, what ho!

Well, this last month or so has been splendid in terms of weather, what? And indeed much has been done outside – archaeology and Where/When stuff.

Anyway… pottery as promised!

So… Master CG has taken up Windsurfing, which is to be applauded. Like a fish to water you might say, and he’s quite good, apparently (the instructors seem to be very pleased). This means that for a few hours at a weekend, myself and Mrs CG get to relax at the wonderful Glossop Sailing Club (who I cannot recommend highly enough – they are simply amazing), and in the neighbourhood of the wonderful Torside Reservoir in the Longdendale Valley, surrounded by the glacial formed hills; it’s truly a wonderful landscape.

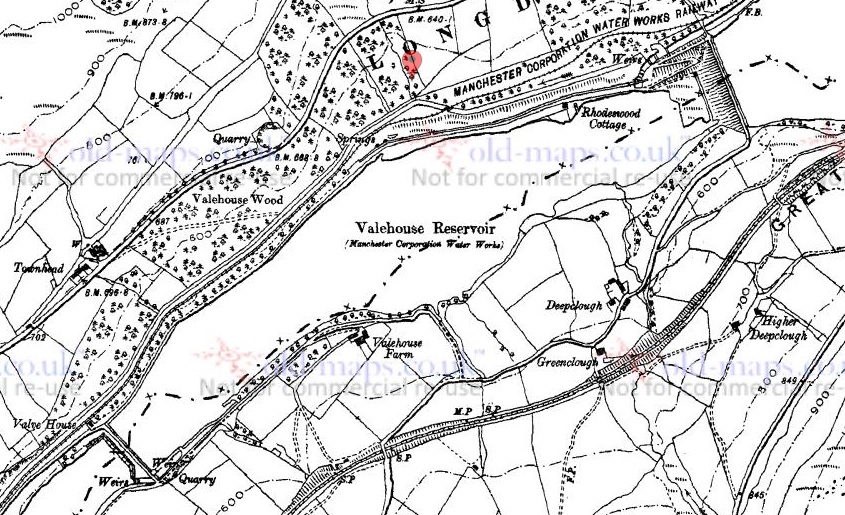

Torside Reservoir is the fourth, and largest, in the Longdendale Chain of reservoirs which flooded this part of the valley in 1864. It is named after Torside Farm, first mentioned in the baptism of Alycia Hadfield in All Saint’s, Glossop, on 16th July 1621. Now whilst this may be the first mention, for two reasons I had a feeling the farm would be older: firstly, Alycia clearly had parents who didn’t just pop into existence in 1621. And secondly, if a place is good for farming in the 17th century, it would have been good in the 13th, 14th, and 15th centuries.

Interestingly, this first mention in the parish register was actually written as “Thorsett” which, like many others in those pages, is a remarkable fixed record of the local dialect and pronunciation of the 17th century; the clerk asks “where do you live” and the answer from the parent is “Thorsett”, which is then written precisely as said, in clipped northern tones. Even as late as the 19th century, spellings of names and places is not fixed, and confusingly there is often quite a range of spellings for a single farm. Alas, the farm seems to have been demolished by the 1960’s, probably by the water board, and where it stood is now the carpark and public toilets.

Now, knowing this, and whilst young CG was floundering in the somewhat chilly waters, I went for a wander with the hope of finding something interesting and ceramic with which to entertain you wonderful people. Along the edge of the water, and up to the road I walked; I didn’t know what I was looking for as such, more a vague sense that something would be there, this close to an early 17th century farmhouse. And lo! What wonders did appear…

Firstly, I noticed two long walls amidst the general stony foreshore. Made from large boulders that would have, at one time, been plentiful in the fields; they were a convenient source of stone, as well as clearing the fields allowing them to be ploughed effectively.

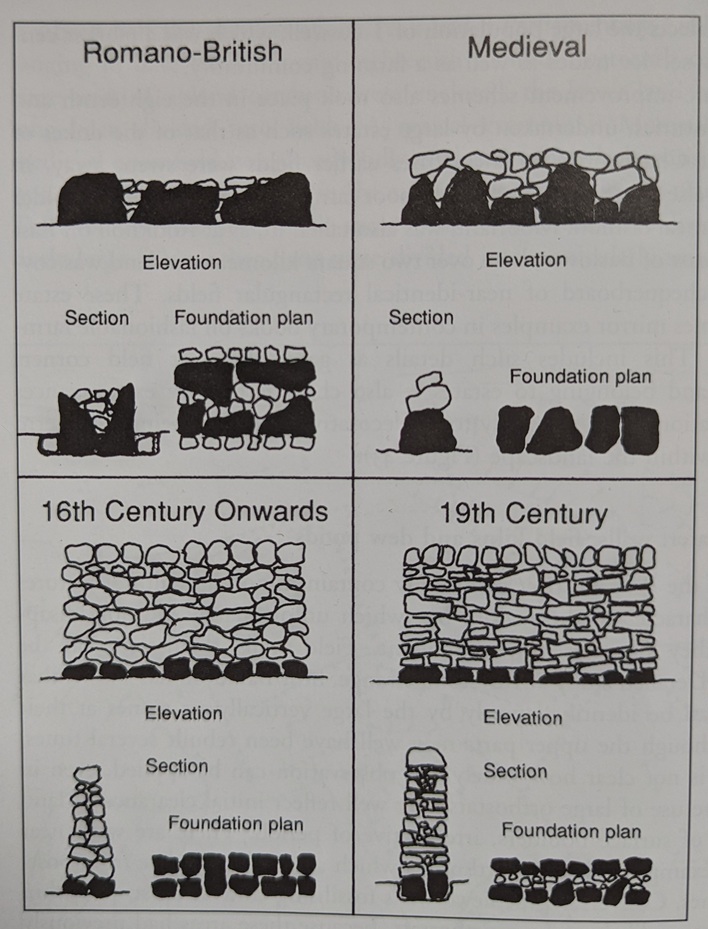

They would originally have stood higher, with this being the foundation course, and the size of the stones, combined with the lack of any map evidence, suggests an early, possibly medieval, date. There is a rough guide to dating walls in this area and hereabouts:

It is a rough guide, and isn’t probably applicable everywhere, but it does serve to show differences in how walls were built. I honestly don’t know what these are, but I’m presuming field boundaries for a long lost field system. There are medieval field walls in Tintwistle, and they do look like this, but equally I have seen field clearance walls that date to the Bronze Age that look similar. The following is a rough map and rough measurements – maybe I should go back and really survey the walls properly… anyone fancy helping me?

But enough about the walls, “show us the good stuff… the pottery!” you shout (all except Mr Shouty-Outy, who shouted that he would apparently rather see my bottom…). Well here it is. The pottery that is, not my bottom.

All this was found on the surface, and it tells a very interesting story, but there are some genuinely important bits here. First up, we have a sherd of Manganese Glazed pottery.

Early 18th century in date – it stops being made around 1750 – this stuff is fairly commonly found on sites of this date, and probably come from a jug or mug. I explored this stuff here.

Other bits of Manganese Glazed include these 4 rim sherds from cups and mugs.

Clockwise from top left: an open bowl measuring 16cm, a cup of 10cm, another cup of 10cm, and another measuring 12cm. Lovely stuff.

Next up, some slipware.

On the left, a chunky sherd probably from a large jug or similar. On the right we have the rim from a large platter (it has a rim diameter of 30cm); the piecrust edge is hugely characteristic and immediately recognisable (again, I explore it in this article):

The middle sherd is Staffordshire Slipware, with a Dark on Light decoration. The reddish slip laid over the light background turns much darker when covered in the lead-based glaze. In this case it seems to be giving some form of geometric design – you can see the grooves where the slip was laid, but which has fallen away – the pottery is not particularly hardwearing, and the slip is often found to have delaminated from the body.

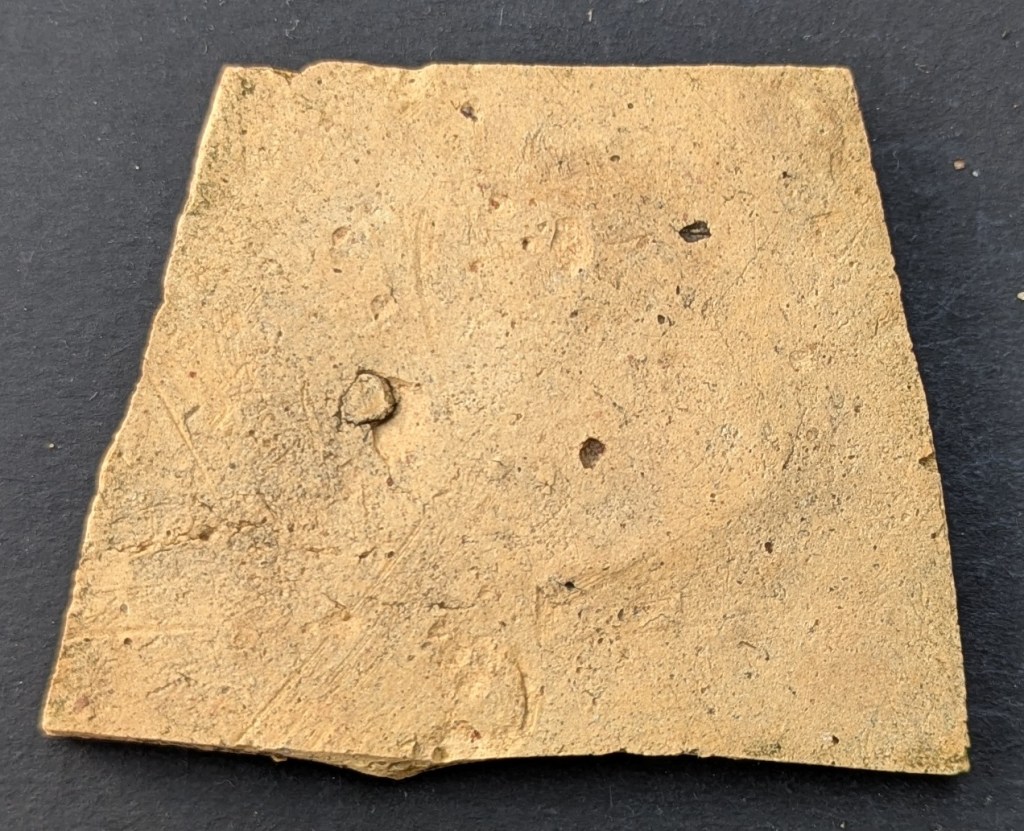

This is from the base of the vessel – probably a large platter used for presenting food on the table, and from which all the family would have taken their own share. Turning it over, you can see lots of interesting marks made during the manufacturing process.

When made, the pots are pressed into a mould until they are ‘leather’ hard – that is, hard enough to retain their shape, but not quite fully dry. What we can see on the base are the scars of manufacturing. There are numerous lines scraped into the clay, suggestive of tools used to remove the pot from the mould, or even string. There is also a small ball of clay lodged within the base – this would have been dry and sitting in the mould when the wet clay was placed in it, and when removed it became part of the base. The small holes around it suggest that there were others that didn’t become attached. I love this… it’s almost the secret side of pottery – whilst most people look at the decoration and say “oooh”, let’s instead flip it over and see what else it can tell us.

Next up, we have some Nottingham Stoneware:

I explored this wonderful stuff back in the first instalment of the Rough Guide to Pottery so I won’t discuss it here, but it dates to the 18th century, which is a good date for us. You can see the ‘orange peel’ surface made by using a salt glaze in this sherd:

And on this sherd interior, you can see the horizontal smoothing lines.

I think 2 of the sherds come from jugs or bowls, whilst the base sherd on the left has a diameter of 7cm, so it might have come from a squat round-bellied tankard.

Slightly later than all this is a beautiful sherd of Industrial Slipware:

It’s a lovely fragment of a sugar bowl type thing, with a wide mouth and straight sides. I like how the decoration gently mirrors the environment it was found in – very suggestive of water and sky.

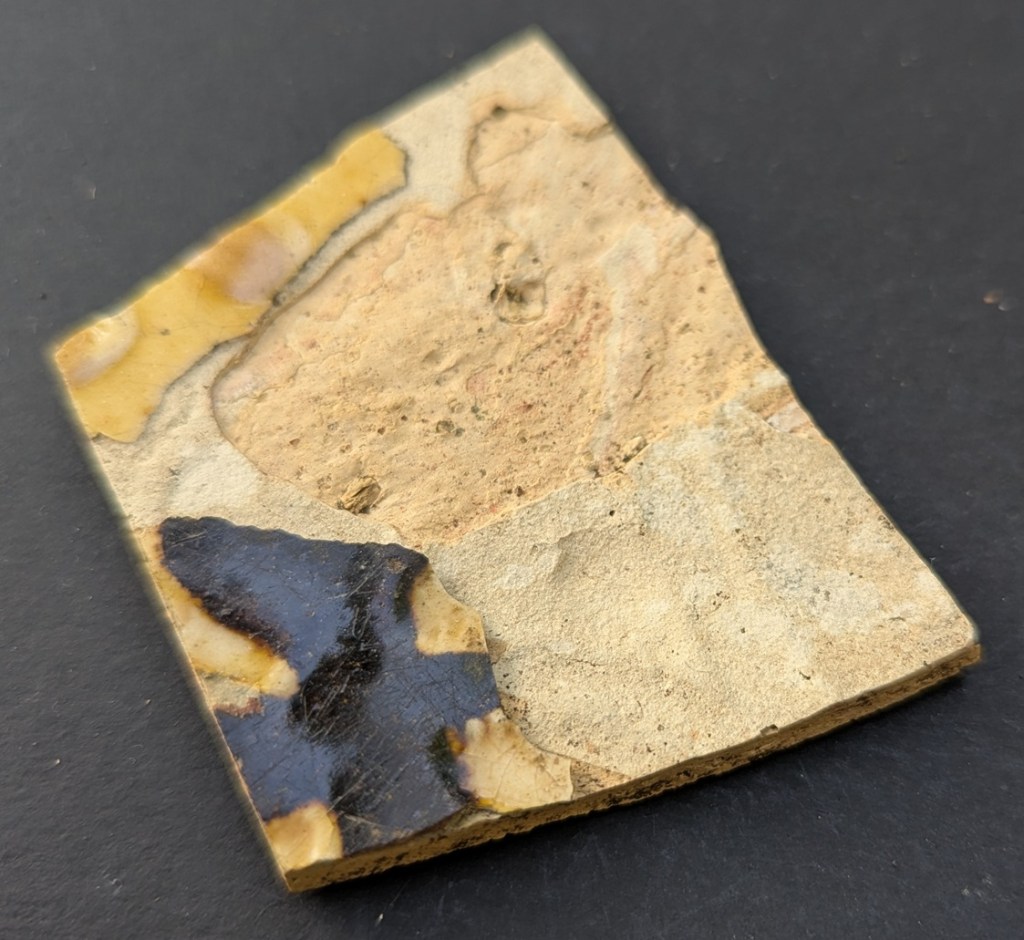

For me, though, the absolute gem of a find was this fragment of a large Cistercian Ware jug.

Dating to the earlier 16th century (1550, perhaps), this is quite special in that it not only pushes back the date of Torside Farm, it is also not something that is commonly encountered. The surface is wonderful in a deep black glaze, and the fabric is textbook purple and hard, with the classic ‘salt and pepper’ inclusions.

The purple colour is on the bottom, the darker grey colour in the fabric is on the inside of the jug, and is caused by the pot being fired in a reduced oxygen environment – essentially, a lack of oxygen during the firing as air couldn’t get into the jug interior properly.

It would have originaly looked something like this:

Genuinely, this sherd is, I think, something significant and had me all of a quiver when I found it. I had to have a bracer or two, and thankfully I was soon back to my normal stiff upper lipped-ness.

I also found some clay pipe stems here and there amongst the stones; all fairly standard and Victorian with the remarkable exception of this wonderful fragment.

It is chunky, being some 10mm thick, but crucially it is a large bore – the hole through the middle is 4mm – which is unusually large, and twice (or more) the width of a Victorian bore (sigh… yes thankyou Mr Shouty-Outy, calling me an ‘unusually large bore‘ says more about you than it does me). All of this means that the stem is early; early 17th century early… probably the same date as the earliest reference to the farm in 1621. It’s wonderful to imagine Alycia’s father sitting and smoking a nervous pipe in front of the fire, listening to the cries of his newborn daughter upstairs, and who knows… this could be the pipe. I love this, genuinely… it makes it real.

I also found a fragment of stone roof tile with the peg hole intact…

Slightly older… glacial erratics – bits of stone that are not part of the local geology, which in out case is Millstone Grit and coarse sandstone:

I talked a little about glacial erratics here, but essentially they are bits of stone that have been picked up from all points north of here by glaciers moving south during the last ice age (granite, and large bits of quartzite, for example). The movement of these huge structures made of ice, mud, and stone, actually carved out the Longdendale Valley, and when they began to melt roughly 25,000 years ago, they dropped all this odd material. Glacial sand and clay can be found all over the Glossop area (my own house sits on glacial clay), but it is very prevalent in Longdendale. The types of stone, and indeed origin of these, I haven’t gone into; I am not a geologist, but perhaps I should write an article on them?

In addition to all that, I found a rather nice segment of hand forged, very worn, iron chain.

I have no idea of the age of it, but it’s certainly at least Victorian… and is very cool!

As I say, the first mention we have of the farmhouse at Torside is 1621, but I am fairly confident that the Cistercian Ware jug is earlier, and perhaps by as much as 150 years – which is very interesting and may point to an earlier incarnation of the farm in the area… which makes sense. The past is indeed all around us, and often at our feet… and it is always well worth having a look.

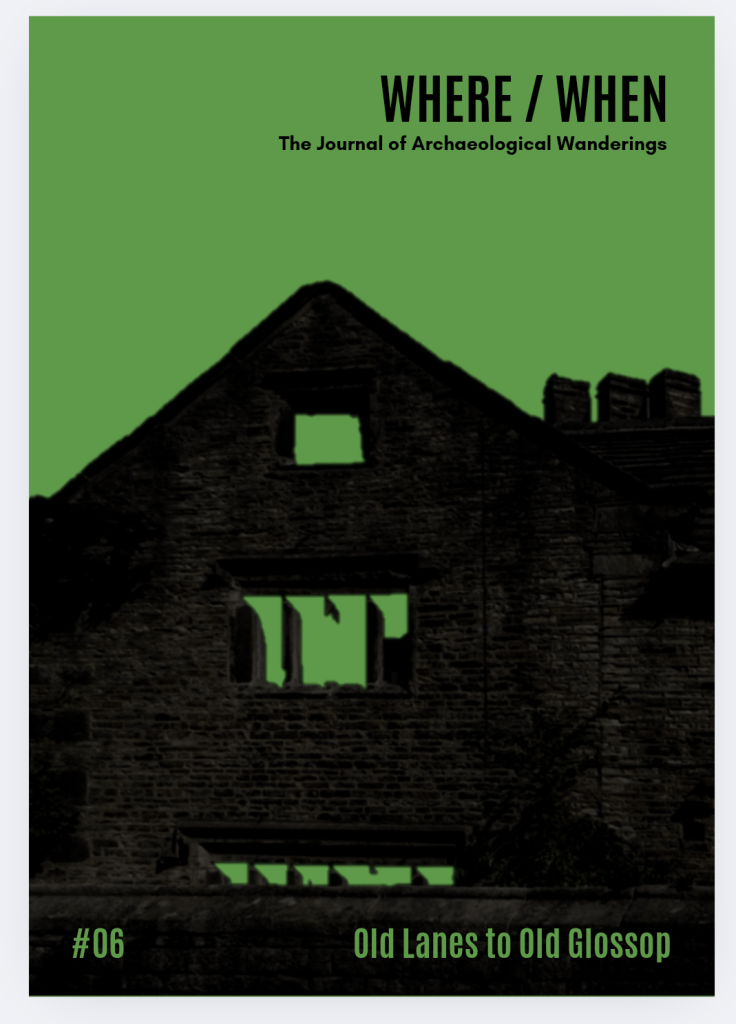

So then, in other news (and also having a look at), the new edition of Where/When has just come from the printers: No.6 – Old Lanes to Old Glossop.

This one is a Wander along the medieval main route between Simmondley and (Old) Glossop, now fossilised into footpaths and odd tracks between buildings. Filled with all manner of archaeological goodness and the usual nerdiness, with a pinch of psychedelia and a heavy hit of psychogeography. Put simply it’s a bloody good walk that goes between The Hare and Hounds and The Wheatsheaf, so what’s not to love?

Contact me here, buy it in the website store, buy it from my Etsy store, the Ko-Fi store, stop me in the street and say “what ho!”, or pop into Dark Peak Books on High Street West, Glossop and grab a copy. It is selling fast… worryingly fast, to be honest!

Right, I think that’s all for the archaeology this month… more soon, obviously. Perhaps more pottery; I’d like to finally wrap up the Rough Guide to Pottery – its unfinished status is frankly bothering my diverse and somewhat spicy mind, and I’d like to be able to wake up not screaming once in a while! Watch this space.

In the meantime, as always – and I do honestly mean it – look after yourselves and each other. This world is not always kind, so let’s – even you Mr Shouty-Outy – try and be kind instead. Until then, I remain, your humble servant.

TCG