What ho, dear and lovely people, what ho! I trust you are all enjoying the weather as it bounces, somewhat insanely, from parched desert in the midst of an African heatwave to “quick Mrs C-G, gather up two of every animal you can see, whilst I look up ‘How To Build an Ark‘ on YouTube” rainstorms. I mean, it keeps you on your toes, what!

So then, I have recently become obsessed with fields and their shapes, and what they can tell us about the history of Glossop. I know, I know, I really am quite the hit at parties! Indeed, I often hear the phrase “oh great, TCG has arrived!”… it’s nice to be appreciated. As an aside, 7-year-old Master C-G has recently taken to mocking me by asking a question about, for example, pottery, and then interrupting the answer with “wow dad, that’s soooo interesting…” and walking off, before falling down in fits of laughter. I mean to say, that’s a tad off, what? Where’s the blighter’s respect for dearest pater?

Anyway, where was I? Oh yes, field shapes and history. So, if you look at any OS map, you’ll see that it is criss-crossed with lines which mark out the boundaries of fields. On the ground and in real life these boundaries are made up of fences, hedges, or, in this part of the world, with drystone walling. It takes time and effort to build these walls, and more time and effort to take them down, which means it doesn’t happen very often. And unless the area has been significantly changed or has been built over completely, the field boundaries you see on the map and on the ground have been there since they were laid out. And here it gets interesting: the way fields were laid out changed over time – their shapes reflecting contemporary farming techniques – and it this which allows us to date them and their associated settlements.

Looking at local examples chronologically then, we start at the beginning. Quite literally. The first farmers – those neolithic & bronze age types who initially took the huge risk to cease the hunter-gatherer nomadic lifestyle, and instead adopt a sedentary one based around agriculture – created the first fields. Evidence from elsewhere suggests that these were not fields as such, more areas of land cleared of trees – a formidable task using only stone or at best bronze tools – and the area cleared of stones to enable to plough to pass. The larger stones are normally found rolled to the edges of the cleared areas, and there are often clearance cairns associated with them – piles of rocks, essentially. There are suggestions of bronze age systems in the area, but nothing even close to definite, and certainly nothing worth describing.

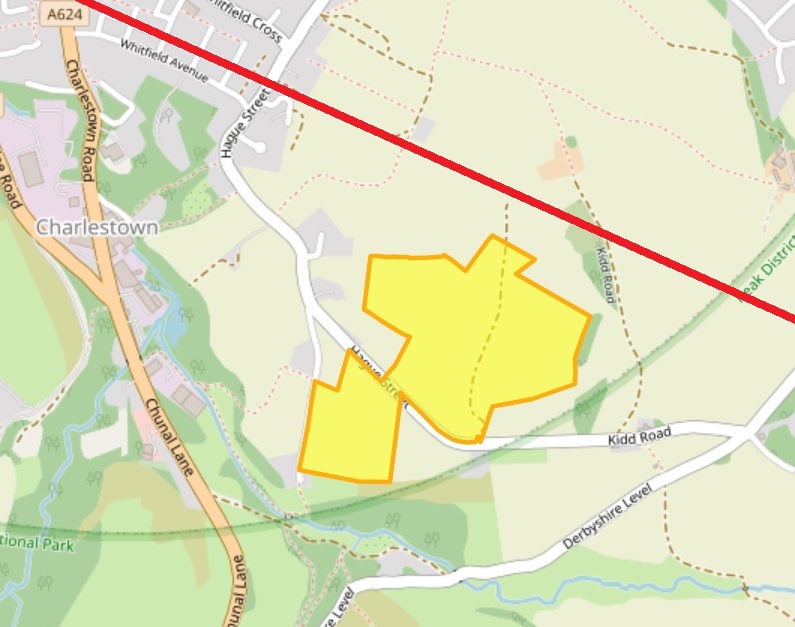

There is a similar situation with the Romano-British field systems, of which there is one possible example, in Whitfield, to the north and south of Kidd Road. These seem to comprise a series of lumps and bumps in the ground that might be the remains of field boundaries, or of terracing on which agriculture took place.

As the Roman road from the fort at Brough (Navio) runs just by there, it would be a good place for a farmstead, and I’m sure more existed nearer Melandra. It’s not terribly inspiring, if I’m honest, but it is interesting, and if it is Romano-British in date (43AD – 410AD, perhaps a little later, too… or possibly a little earlier), then it is proof that people have lived and farmed in Whitfield for over 2000 years. You can read a bit more about it on the Derbyshire Historic Environment Record here, or, the Glossop & Longdendale Archaeological Society website, here.

However, our first definite and recognisable field systems occur in the medieval period.

By 1086, Longdendale and Glossop had been designated Royal Forest, a situation which brought with it all sorts of restrictions for the residents of the seven villages that made up the area at the time of the Domesday Survey: Chunal, Whitfield, Charlesworth, Hadfield, Padfield, Dinting, and Glossop (I’m convinced there was something at Simmondley and Gamesley at the time, but were overlooked or ignored as too small to tax). It was particularly particularly restrictive around land use; the existing villages were allowed to continue, but were not allowed to expand their size in anyway, as this would affect the king’s land, and take food from his deer. That didn’t stop them, though. What few records we have of medieval Glossop make mention of the crime of assarting, that is to cut down trees to enable the land to be used for growing crops or grazing – essentially increasing your land, illegally. For example, in 1285 we find the following:

“The wood of Shelf has been damaged in its underwood to a value of 15 shillings by the villagers of Gloshop, fined 4 shillings, they must answer for 60 oaks”.

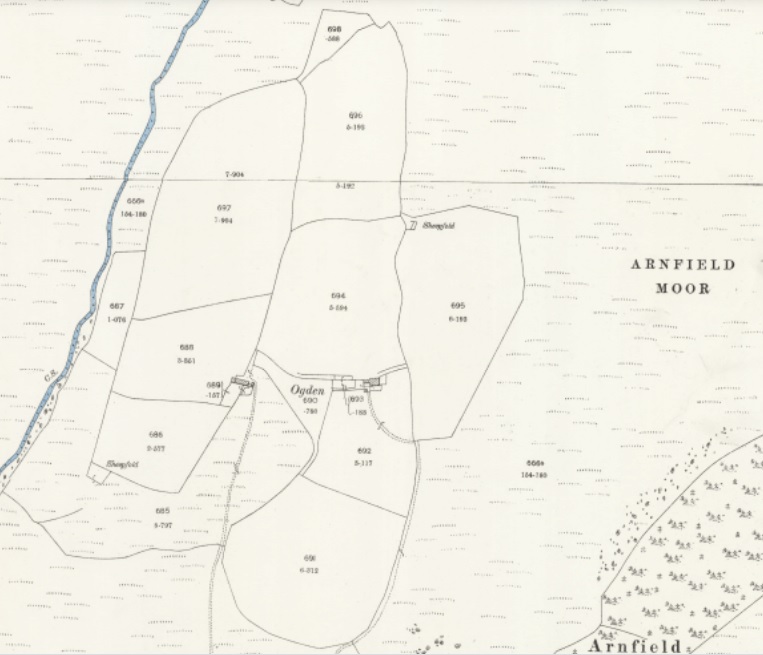

The process would have been gradual, and probably done sneakily, perhaps by bribing the forester to look the other way. Or equally, it may have been worth the fine if you can increase your farming lands significantly – an investment of sorts. Given the nature of assarting – essentially picking away a few trees at a time – it often leaves a distinctive field shape: rounded, rather than straight or uneven lines. There is a perfect example of this at Ogden, above Tintwistle:

And if we look over at Hargate Hill, between Charlesworth and Simmondley, I think we can see a similar process happening here:

The circular, almost organic growth of the fields can be seen, and it may be this that is referred to in 1285: “The wood of Coumbes (Coombs) has been damaged by the people of Chasseworth (Charlesworth), fined 2 shillings, they must respond for 18 oaks.” This whole area is full of interesting detail. The first mention of Hargate Hill I’m aware of is 1623 (the record of the burial of ‘Widow Robinson’ of Hargate on 10th July, to be precise), but there must have been something there before this date. There is a suspicion that stone from the quarry here was used to build Melandra Roman fort, although how true this is, is not clear, but the settlement is just off the main road between Glossop (via Simmondley) and Charlesworth, which is significant. Importantly, between the road and settlement, there is evidence for Ridge and Furrow ploughing, which is normally medieval in date. You can see it in this LIDAR image:

Ridge and furrow is created by ploughing up and down a strip of land using a team of 8 oxen. Now, as you can imagine, 8 oxen are a nightmare to turn, and their size alone means that you have to start the turn very early on in your plough furrow in order to maximize the land use. This creates a distinctive reverse ‘S’ shape to the thin fields – or ‘selions’ – that make up the medieval farm landscape – the result of only being able to turn the oxen to the left (as the medieval farmer used a fixed blade plough share that was positioned on the right). These selions are side by side, with a dip in between (you can just about make out the dips in the above LIDAR image), and made up of rows and rows of ridge and furrow running the length of the selion. A selion normally measured a furlong in length (a ‘furrow long’: some 220 yards) and between 5 and 22 yards wide.

In Whitfield there are many great examples of this classic, and instantly recognisable, early medieval field shape.

Hiding in plain sight, the medieval field systems of the 12th & 13th centuries. The fact that they run either side of Cliffe Road is significant: they ‘respect’ the road, which means that the road was there before the selions, as it is highly unlikely a road would be put through arable land. We know this anyway – it was the main road from Glossop to Chapel en le Frith – but it is good to have it confirmed.

What I find amazing me is the sense of continuity of use; the field marked with a red ring in the above map is exactly the field boundary of the Whitfield Allotments, and I wonder how many allotment holders realise their plot of land has been continuously farmed for nearly a millennium. It’s also fascinating to think that although the area has been largely built over, the boundaries of individual modern house plots have used these field boundaries as references, and so the field laid out by a medieval peasant farmer 800 or more years ago has a direct influence on life today. Looking at a tangible history in that way leaves one feeling quite dizzy.

Chunal is even clearer in its agricultural history, and has evidence of both assarting and the use of Ridge and Furrow on both sides of the road, especially what is hidden beneath the surface now – compare the above map with the LIDAR survey of the same area… huge numbers of selions, all in the classic reverse ‘S’ shape.

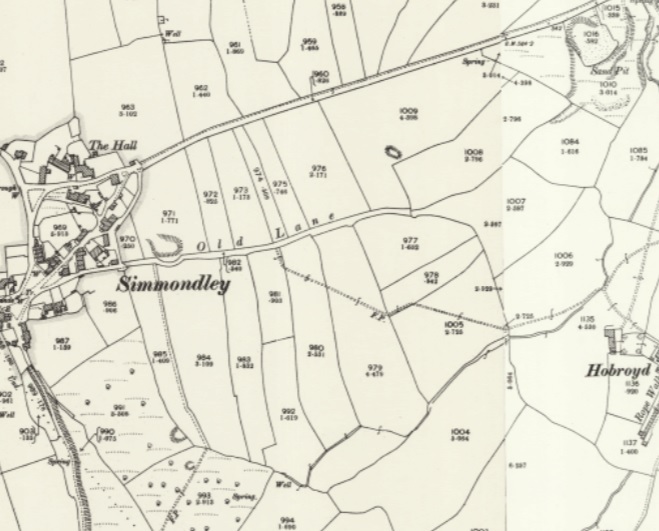

The quantity of field strips is testament to the relatively large-scale agriculture occurring in this area in the earlier medieval period. Simmondley, too, has a large number to the north and south of Old Lane, which was the original medieval track from Charlesworth via Simmondley to Glossop:

Notice the selions ‘respect’ the original track – Old Lane – they stop at the road, and don’t line up symmetrically on the other side. They are, however, overlain by the New Road which was built, I believe, in the 1860’s. Just as in Cliffe Road in Whitfield, Old Lane must have been there when the selions were laid out, or at the same time, giving us a date for the track.

During the 14th century, however, we see a shift in farming practice, and land use moves away from the ‘open field’ system of strips, and starts to become enclosed by walls. This is probably a result of two critical events. Firstly, the climate starts to get colder, which has a negative impact on the ability to grow crops, and which lead to a series of famines. The second was the emergence of the Black Death which killed off 1/3 of the population during 1348-49. And whilst the Peak District emerged seemingly relatively unscathed, no doubt there was a movement of the population to better arable land that had been abandoned, leading to a population decline. It had also become apparent by the mid century that sheep/wool farming was a lucrative market, and thus increasing amounts of land was blocked off to allow sheep to graze safely. These early enclosures are normally recognisable as non-symmetrical enclosures that have largely straight-ish lines, but aren’t a specific shape. We can see some probable examples to the north of Simmondley New Road, now covered by housing but preserved in the 1892 1:25 inch map:

If we look closely we can see these early enclosures are made by consolidating and expanding existing selions, as farming practice shifted from arable to livestock. The more you look, the more the medieval and early modern landscape comes to life.

We also encounter them at Gamesley, now also covered by housing, but perhaps originally associated with Lower Gamesley Farm which may have an early foundation date, even if the present building there dates from only the 17th century (only…!). The settlement is first mentioned in 1285, but actually Gamesley is a Saxon name meaning the ‘clearing (or assart) belonging to Gamall’.

Of course, people needed agricultural produce, and many strips continued to be farmed well into the post-medieval period. Indeed new fields were laid out, although later ridge and furrow is normally straight as, over time, smaller teams of larger oxen were used, and these were eventually replaced altogether by heavy horses.

Our final field type comes at the end of the 18th and early 19th centuries with the parliamentary enclosures. Briefly, open ‘common’ land – poor rough land, owned by the Lord of the Manor, but used by everyone to graze animals or to gather fuel – was parcelled off and sold in lots. On paper, this freed up lots of land and was a boon for farmers who could, with a little improvement, massively increase their lands. But it also meant that the common man lost access to land that his ancestors had legal rights to. Arguably, by the early 19th century there were very few people who would have used the land anyway; not many people had animals to graze, nor did many burn peat as a fuel. The rural way of life, especially in Glossop, was well and truly over and most people lived in stone terraces and worked in mills. But that really isn’t the point! The parcelling up of the land into lots was done drawing lines over maps using rulers… and it shows.

And elsewhere:

Around Lanehead farm, toward Padfield there are clear examples of 19th century enclosure… in fact they are all over Glossopdale – have a look at any map. They often mask earlier field systems and tracks which can be on a different alignment, and a quick scan of the Lidar for the same area reveals all sorts of lumps and bumps:

The grey arrows above show older field systems not shown on the map. In the middle of the arrows there is what might be ridge and furrow. A detailed study of the fields on the maps and on the ground, as well as a comparative reading of the lidar could give us huge amounts of information about the past use of the landscape, beyond the obvious parliamentary enclosures.

The lines of these fields are all very straight, and all the walls are of a standard form, and the whole parliamentary enclosure process was completed with characteristic Georgian and Victorian efficiency. But a part of me feels that it is almost an industrialisation of the landscape, a triumph of efficiency over nature. Prior to this, it was a difficult process to carve out a little patch of land to support your family, and it required blood, sweat, and tears. This human, organic, side is etched onto the land – assarting, the reverse ‘S’ shape, even the enclosures for sheep, they all have an element that is dictated to by the land, and all came with effort. To stand over a map with a pen and ruler dividing up the landscape is to have a complete disconnect from it, and is human imposing on it, rather than working within it, and that feels wrong somehow. Anyway, enough of the hippy!

It genuinely is amazing what you can see when you start to study maps, the unexpected can leap out at you. Keep looking, wonderful people, and please mail me with anything you find – I could even make you famous* by publishing it on the website.

*famous to all 11 people who read the website, that is.

Anyway, I hope you have enjoyed todays romp around the countryside. I’m planning a few more official Cabinet of Curiosities wanders over the summer, one of which is a jaunt down the medieval and early modern trackways of Whitfield and Glossop via 2 pubs and a pile of history and archaeology… what’s not to love? And all at a bargain price… a man has to eat, after all. Watch this space. Or Twitter. Or Instagram, if I can figure how to use it properly.

Until next time, keep looking down, but also look after yourselves and each other.

I remain, your humble servant,

TCG