What ho, wonderful, and slightly odd, folk of the blog reading sort. I hope you are all as well as can be expected, and as we move into autumn, you get out an about as much as you can – always keeping an eye open for pottery and other interesting things.

Which sort of leads me to today’s offering. It’s a mixture, to be honest, some updates, some new stuff, but all interesting. I have said before that I always have multiple half-written articles on the go, all moving at different speeds – but for one reason or another, none leapt out at me asking to be finished. So here we are… Marking Time!

I’ve always been obsessed with the idea of humans marking their surroundings, and the notions of permanence, even immortality, that accompany this; from palaeolithic cave art to bronze age cup and ring markings, to 17th century building datestones, to Victorian carved graffiti, to modern tags – and I’m looking here at you, Boof, whose name is everywhere around Glossop at the moment – it all amounts to broadly the same thing: marking time.

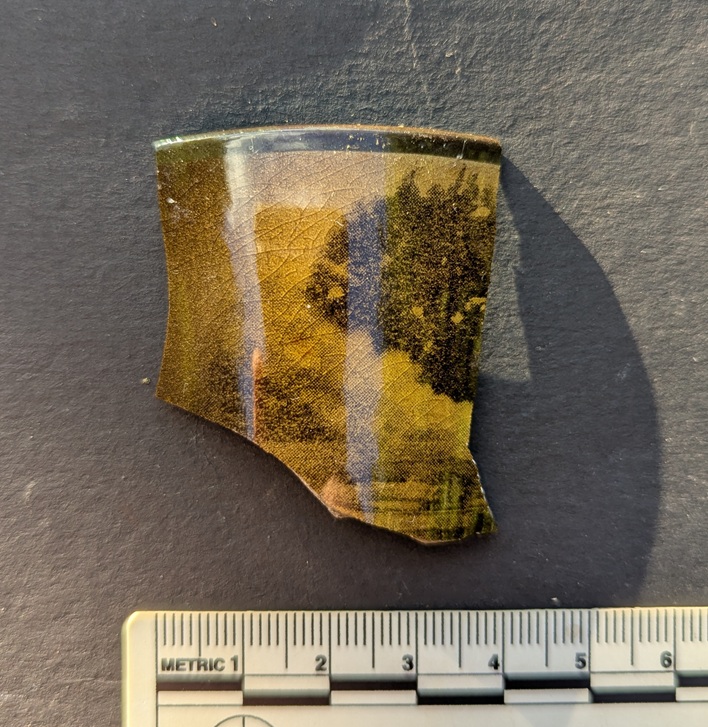

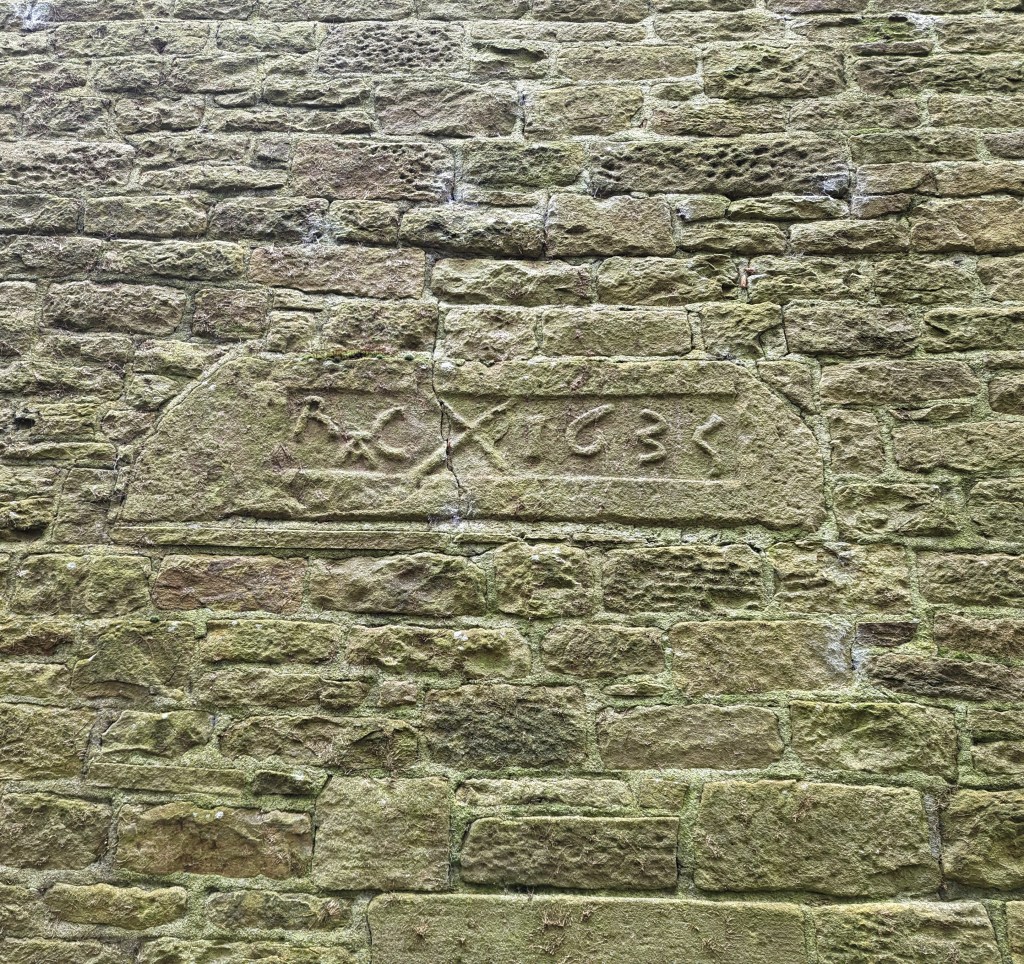

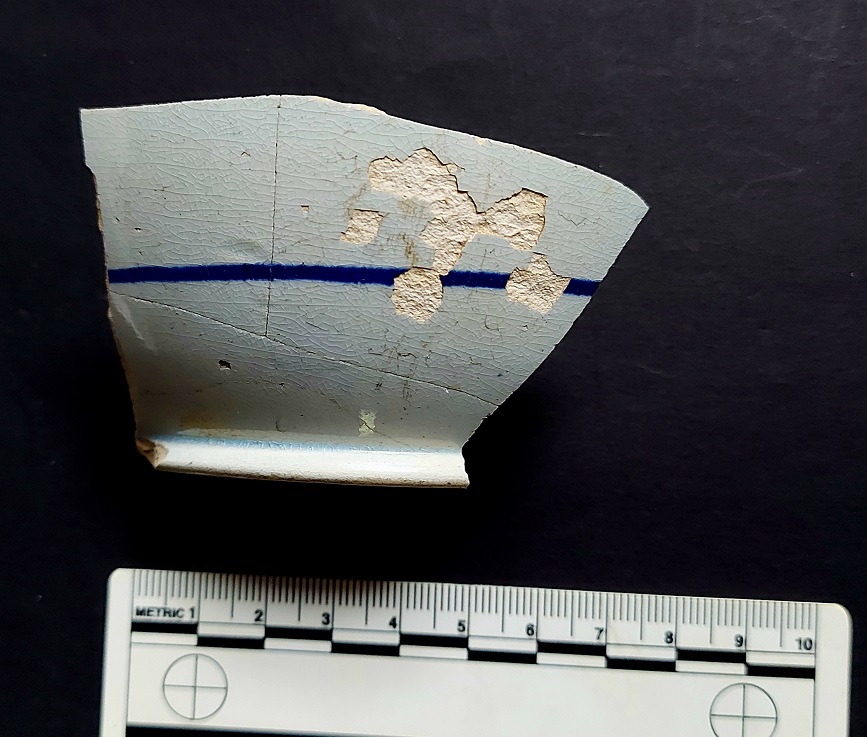

Datestones update: As always, I am on the lookout for more datestones of a pre Victorian date (pre-1837). I recently bagged this:

Wonderful – ‘I.M. 1703’ – to the point, although I have no idea who I (or more likely J) M is. I have a whole article about Herod Farm and the surrounding area in progress, but wanted to share the datestone with you.

*UPDATE*

The always knowledgeable Roger Hargreaves emailed me a comment he tried to post on the site – technical issues prevented it, but here it is:

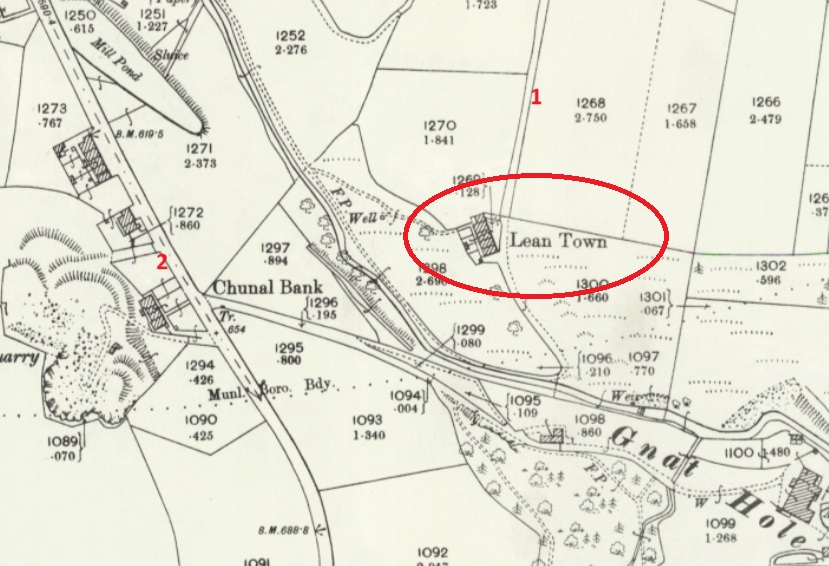

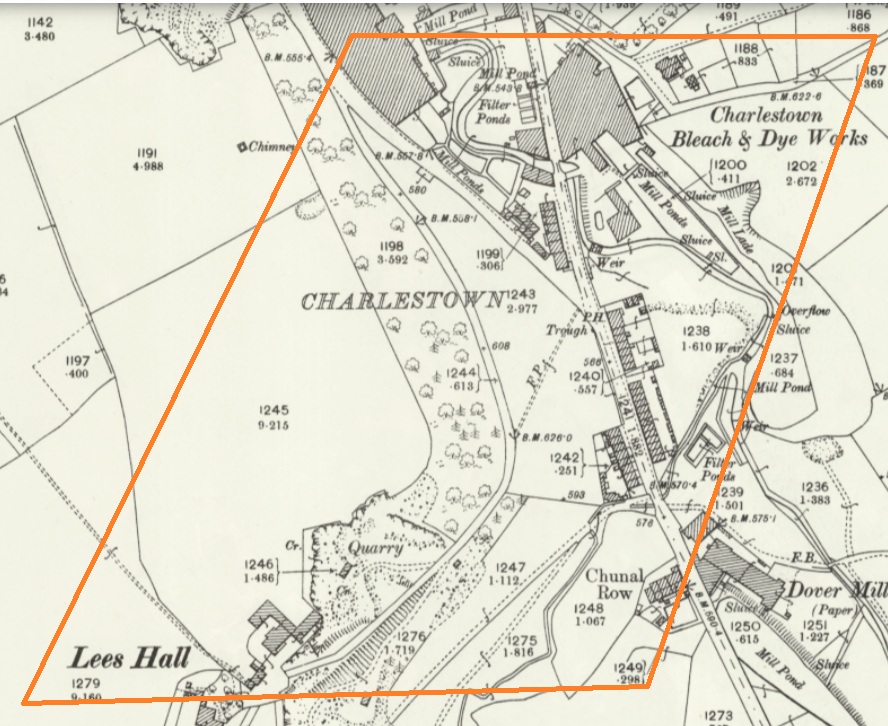

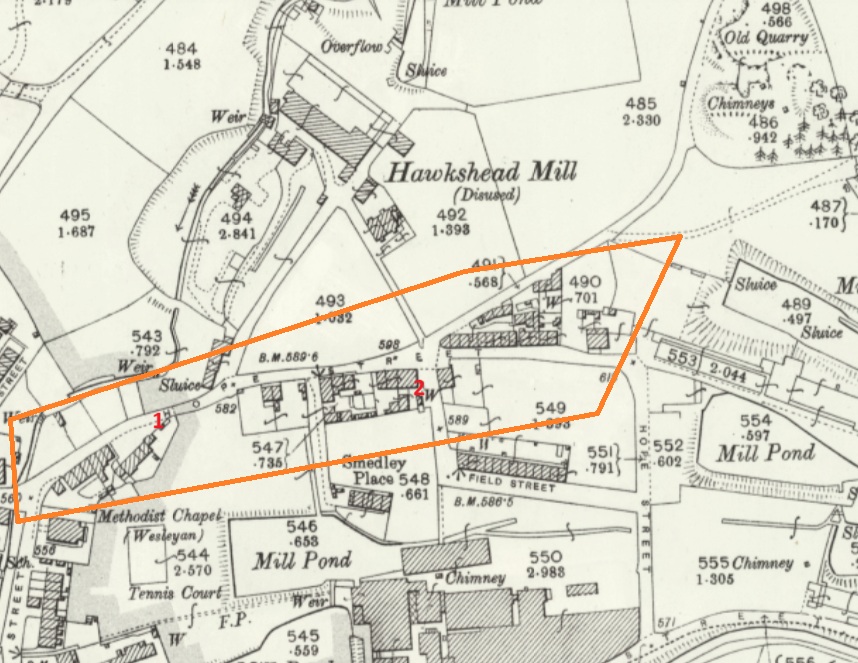

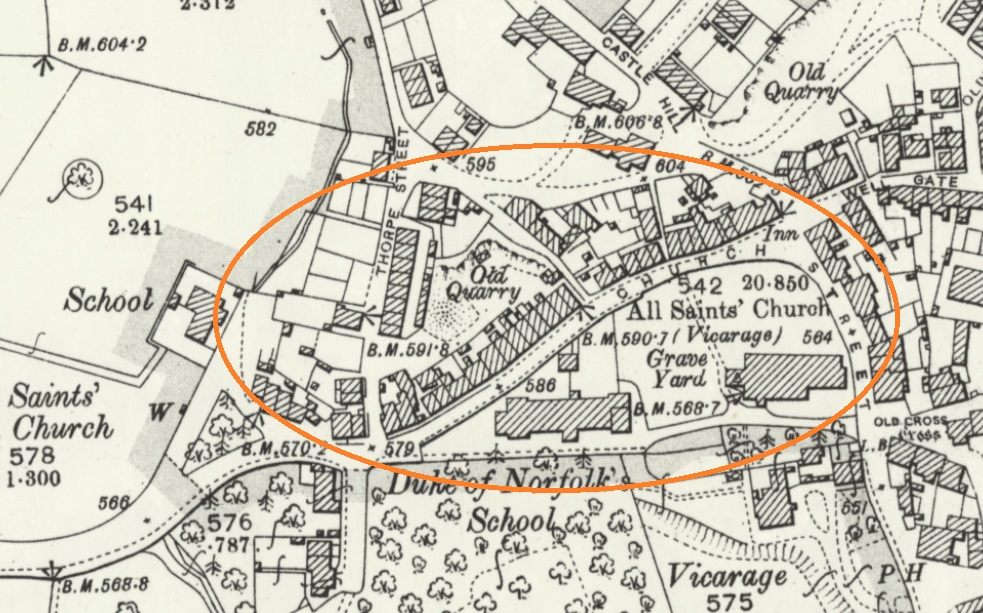

The “JM” on the Herod Farm datestone will be John Morton, who in 1692 succeeded his father, also John, as leaseholder of the adjacent Lees Hall. It’s likely that he then demolished the mediaeval hall which had been the main farming base of the Talbots and before them Basingwerk Abbey as Lords of the Manor. At the rear of Herod Farm is an elaborate window which has clearly come from somewhere else and is likely to be surviving fabric from the demolished hall, giving some idea of what it must have been like.

So there we have it – John Morton, and a teaser about the Lees Hall – a fascinating place, with a long history, and possibly a moat! Well worth an article and more. Thanks Roger, your input is always much appreciated.

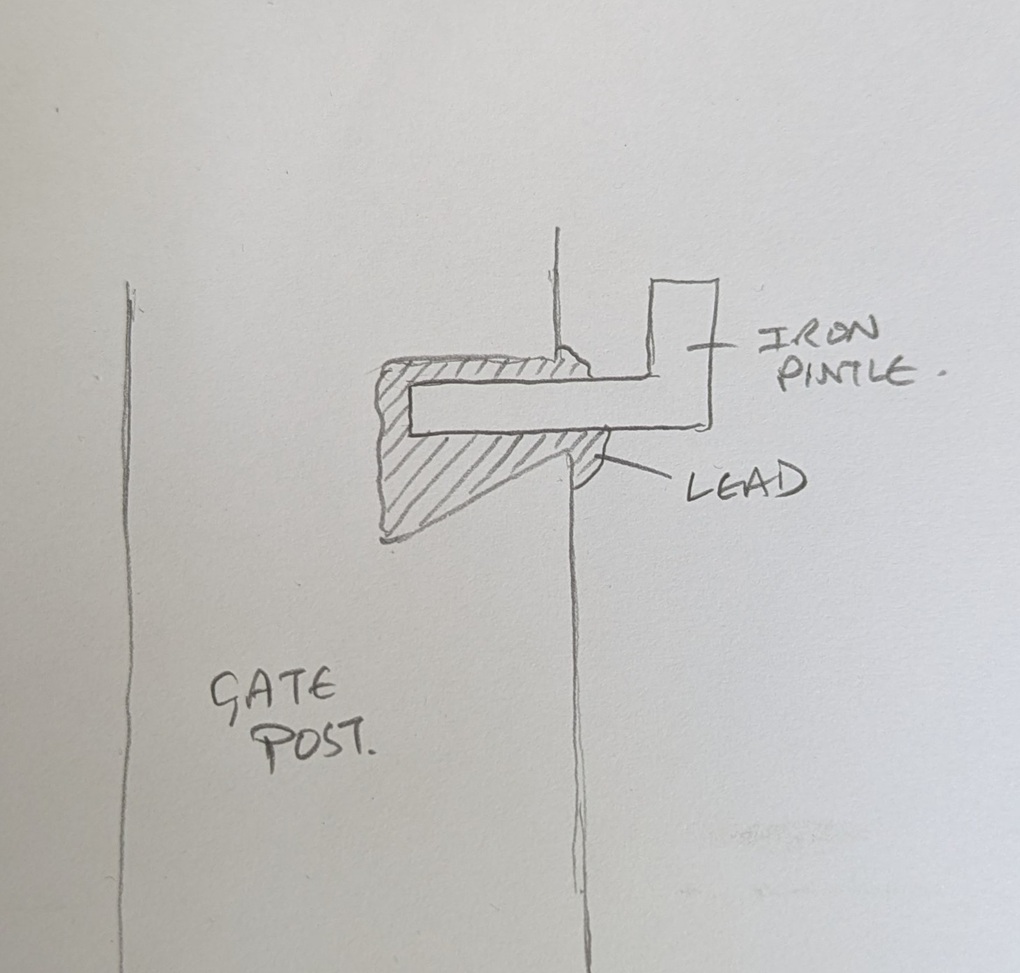

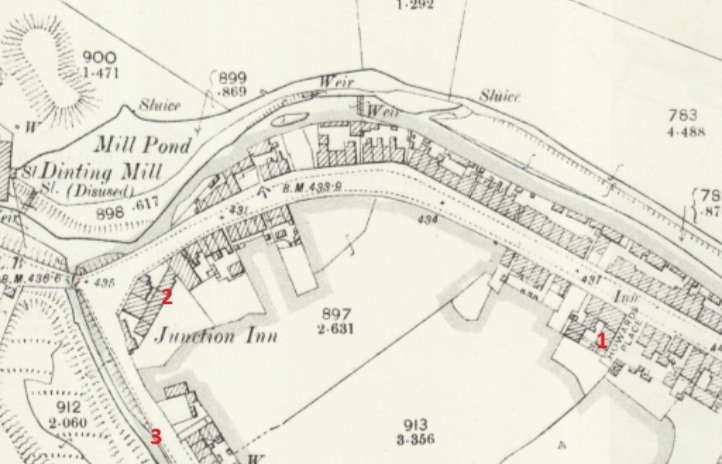

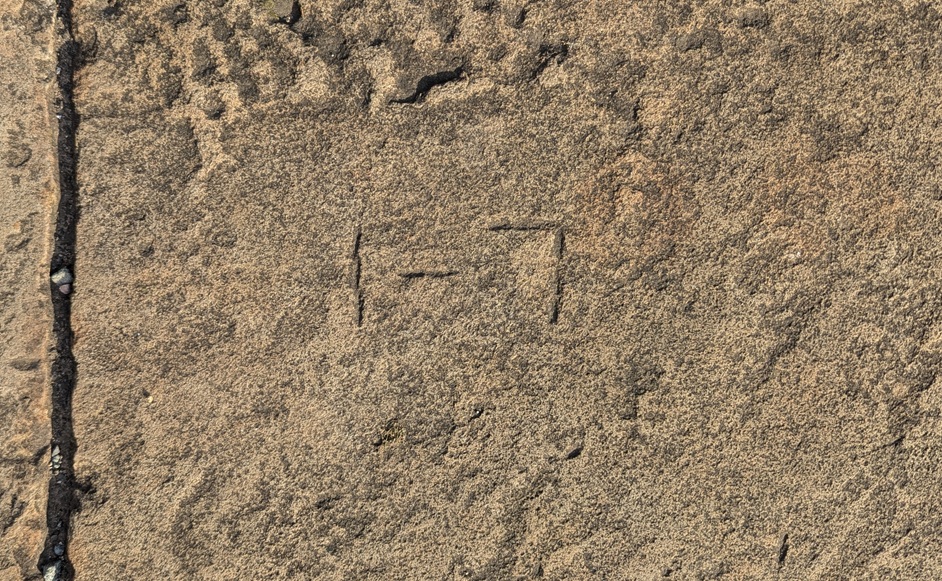

Update to the Gatepost article: We recently bought a campervan, a mobile home with beds and a stove, and all that. It’s marvellous, and is unmissably yellow, or more truthfully YELLOW! (give a shout and wave if you see it around). Our first adventure camping was to Peak Forest, near Buxton, and coming home we decided to take an odd route for the sake of exploration – a vehicular Wander, if you will. Coming through Wheston, south-east of Chapel-en-le-Frith, we came across lots of gateposts, modern and made of concrete, but each marked with initials and dates:

I have no idea who CTH is – presumably the farmer who is replacing gateposts – but I salute your attention to detail – initials and date – and respect your devotion to tradition; earlier, 19th century, examples of dated gateposts can be found here. It might be concrete, but the idea is exactly the same, and I want to buy you, CTH, a glass of the stuff that cheers. Wonderful.

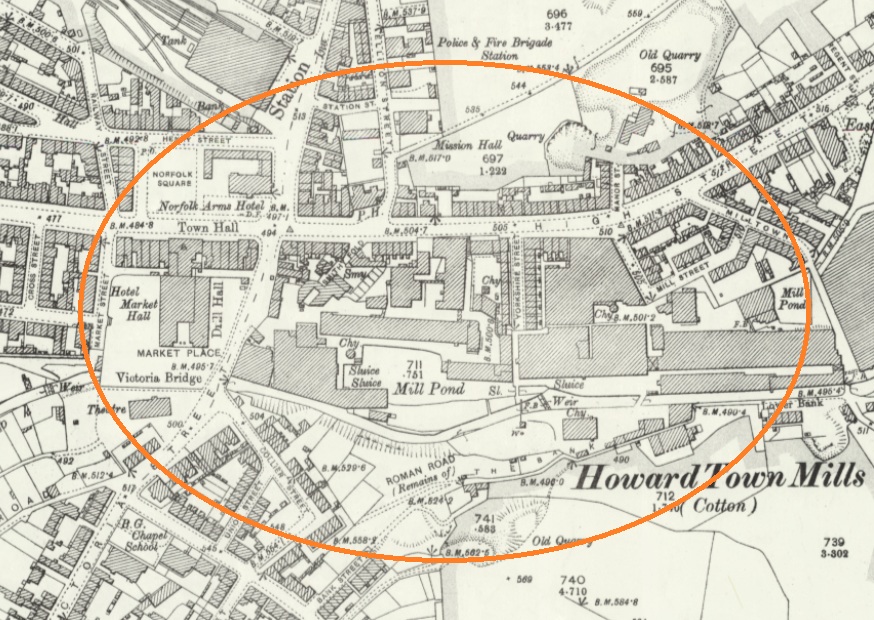

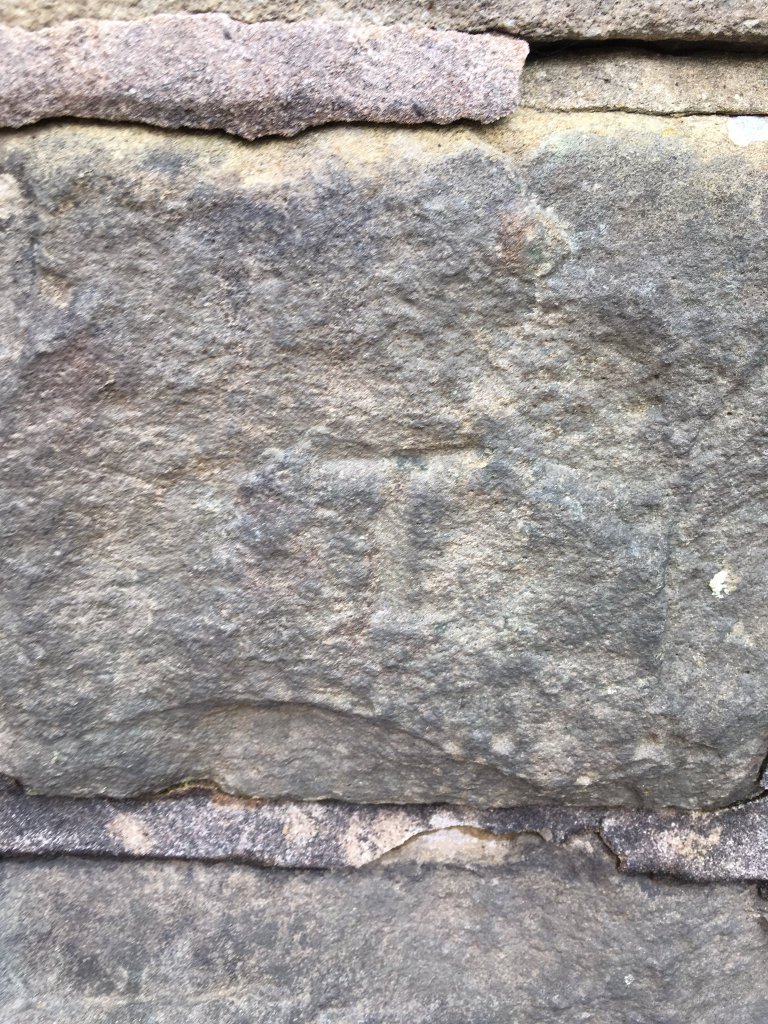

Next we have things seen on pavements… Glossop seems to have inherited the whole street paving slabs second-hand from somewhere. I seem to remember a whole hoo-ha about these stones, and others, occurring maybe 20 years ago – their origin and how much was paid for them… or something. Whatever, but what is certain is that they have some interesting markings on them, and all of these were seen between Costa Coffee and the Norfolk Arms – almost certainly more await discovery, so look down people:

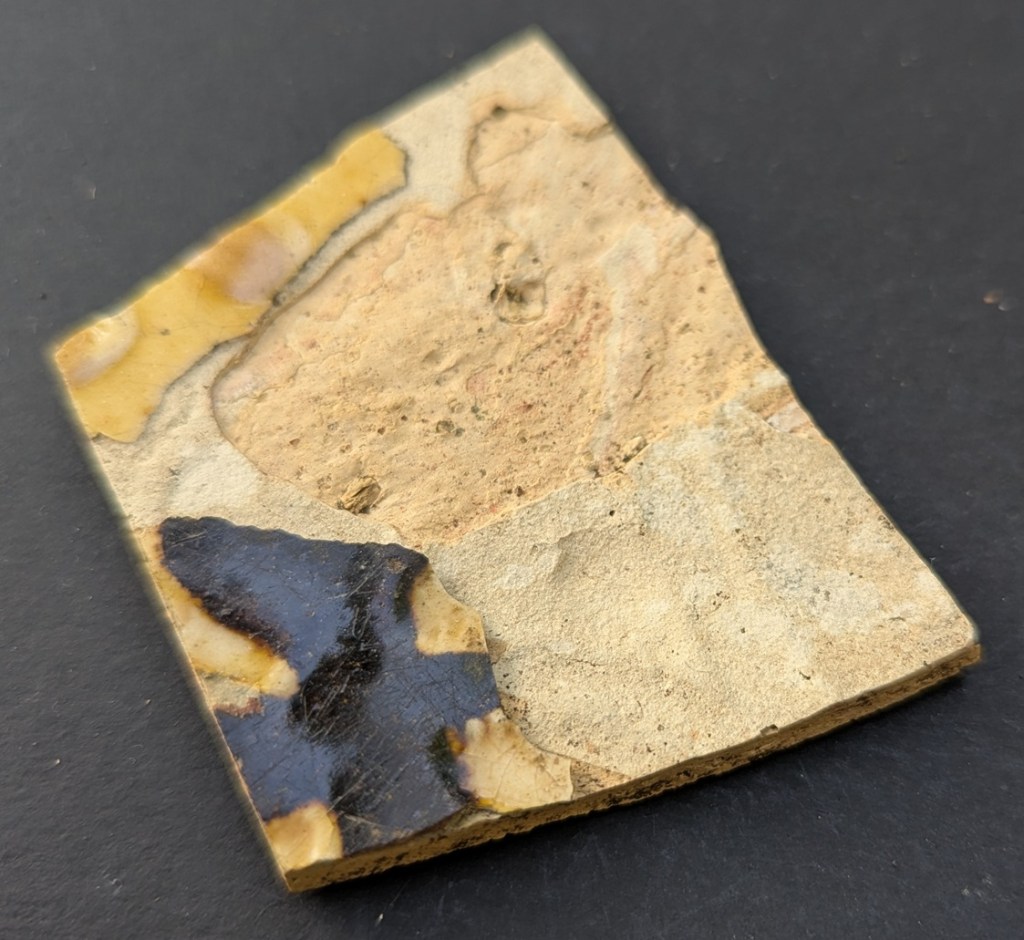

Finally we have this beauty:

So, we have a name in the bottom left, clumsily written – ‘Joseph’ something or other… D? B? Can anyone make out this? The second letter could be an ‘E’. Possibly. But then we have what might be a landscape – the top right looks like a fat sun, drawn by a child, to me. And in the centre, at the bottom, possibly a house (I think I can see the roof and walls, with perhaps a person in it). This is really an enigma – a name, and a piece of art, undatable, and probably from a place far from Glossop… but imagine if we could put a person to it. And all this, lying under our feet.

Other bits and pieces under our feet include markings on kerbs:

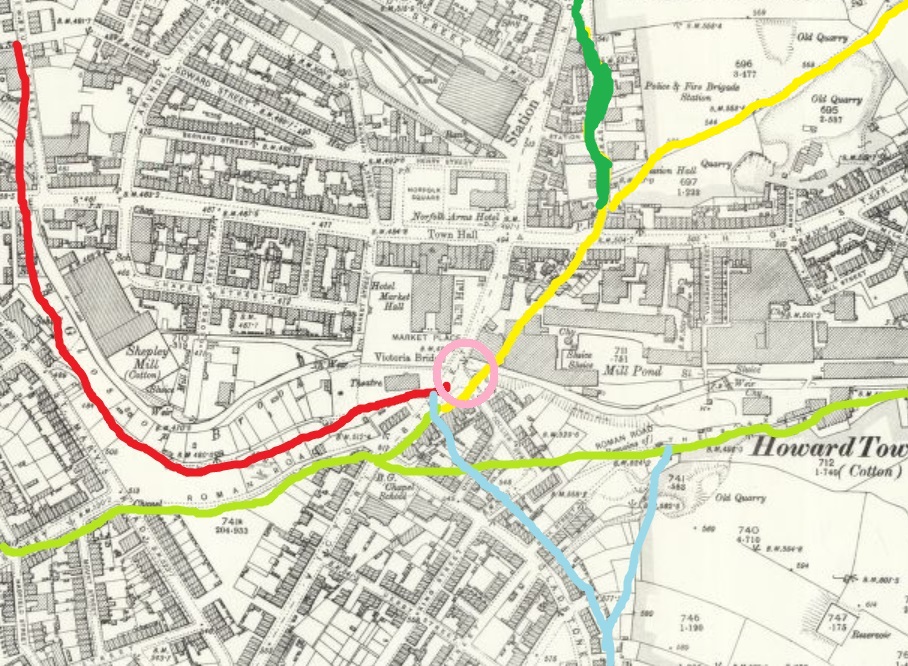

This is also sometimes marked by ‘GPO’ on kerbs, standing for General Post Office who were originally (from 1880’s until 1981) responsible for telephone communications. I once found an example on a kerb on Howard Street, but had not been able to find it since, until I came back from a blood test at the clinic there, and this was picked out of the dark by street lights:

I also saw this on Princess Street – another marker showing where electricity enters a property – this is also quite a commonly found one.

Here’s another mark that is commonly seen: a simple arrow, but not like the Ordnance Survey benchmark arrow, this is normally crudely carved, thin, and without the horizontal line above it… thus:

This is another of those that points to a service – gas, possibly, or electricity – entering a building, although I truthfully don’t know… any help would be welcome.

However, here is a Benchmark, newly found by me, under the railway bridge on Arundel Street, and which marks 501ft 8″ above sea level:

Also on the bridge are these single holes, often found in the upper part of the stone:

And here…

These small, shallow, holes were made in order to use a pincer, or external, Lewis and frame in order to move the blocks. A genius invention, it’s a simple iron tool that, via a chain, uses the weight of the block itself to hold it fast whilst it is moved, and enables even a single person to shift a huge piece of stone. But it requires a shallow hole in order to provide a point that gives a good grip. I love these, as they allow us to view how the bridge was built.

Another example of us viewing the method by which these wonderful Victorian structures were built is this:

Often occurring in pairs, these are drill marks made by quarrymen, into the rock face, which allow them to insert a splitter to pry away the stone from the quarry face. Once seen, they are very recognisable, and are the scars that show how, with a little physics and a lot of brute force, rock can be shifted.

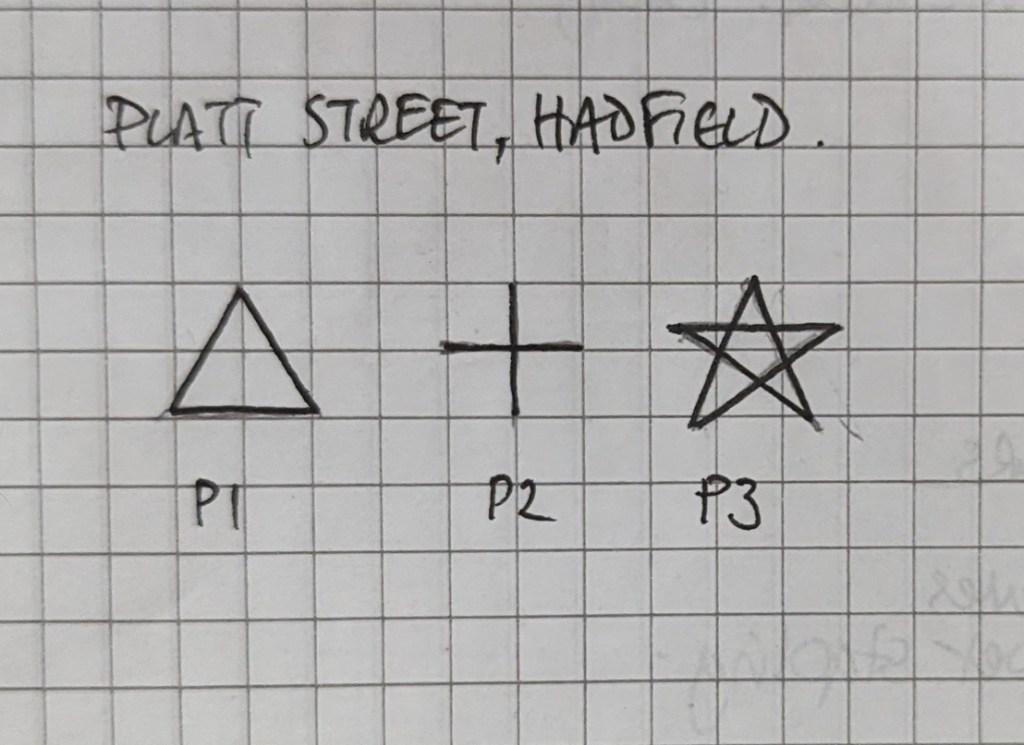

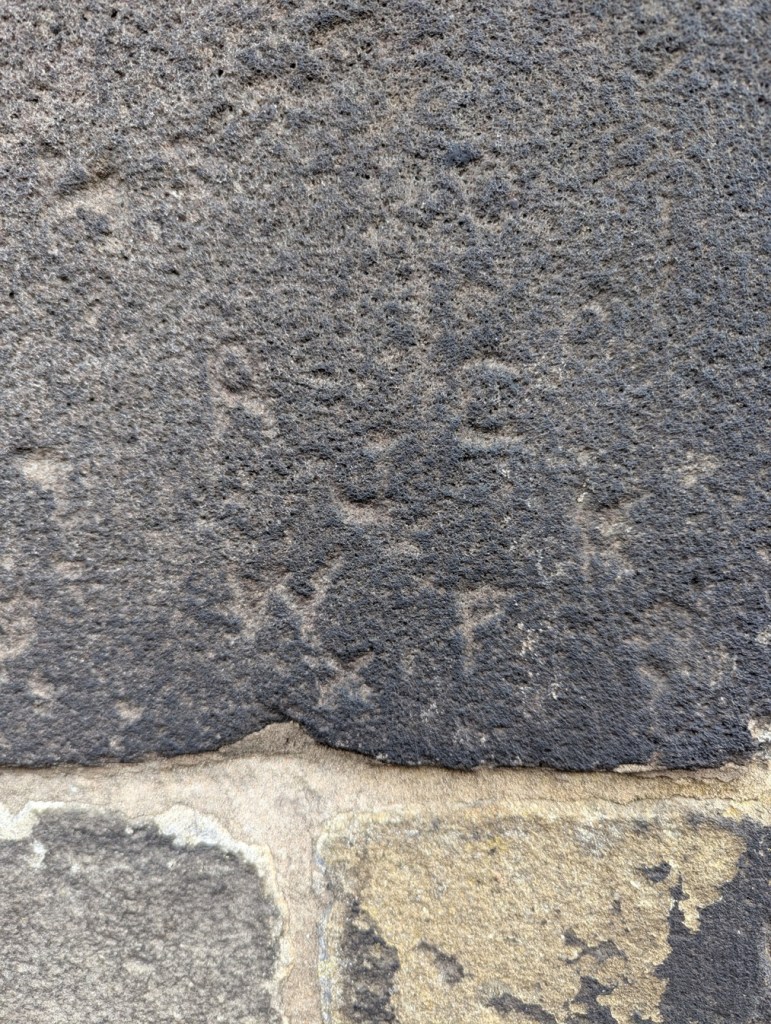

Howard Street, which meets the Arundel Street bridge, has a few, sporadic, mason’s marks along the stretch of railway walling here:

Low key, and not very common, these nonetheless represent the ‘signatures‘ of the men who shaped these stones. The cross is a common mark carved on stones – it is literally two strokes with a chisel – so it cannot be definitively linked to those masons who built Dinting Arches, but you never know.

Other mason’s marks can be found around…

This is found on a lump of masonry from Wood’s Mill, and now stands where Wood’s Mill once stood, now Glossop Brook View, and by the houses there. Post-1842 in date, although possibly early, the mark was hidden until the mill was demolished – the rough dressing of the block indicates that it was never meant to be seen. I wonder who ‘B’ was.

This last one is on the gatepost of the Crown Inn, Victoria Street (although the gates are on Hollincross Lane); very faint – and difficult to photograph – they are in the angular shape of a fish.

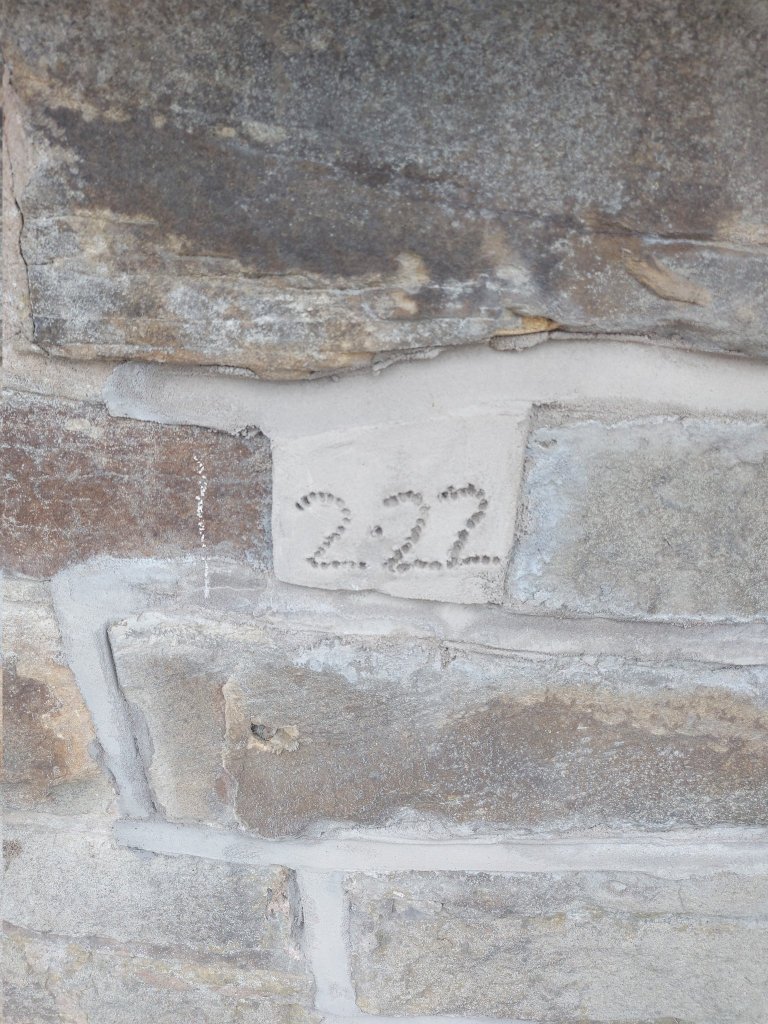

I also spotted this on Howard Street:

A dated piece of cement. This is either dated proof of work done – a modern form of mason’s mark – or possibly a dated repair that allows Network Rail to observe cracks forming and assess integrity. Either way, it’s kind of cool!

Finally, some bits of carved graffiti, a particular favourite of mine.

These last two were from the bridge over the Longdendale Trail on Padfield Main Road. The whole bridge has a lot of graffiti carved on it, including this wonderful example:

Here we have Victorian carved graffiti – ‘J.H’, possibly, along with some more letters, undecipherable under the frost, over an early incarnation of the now famous (infamous) BOOF graffiti tag made with a spraycan. I find it interesting that we would condemn one, but praise the other as historical and interesting. When does vandalism become history and worthy of study? A bigger discussion, and one I find fascinating (akin to when does something become archaeology?). I know graffiti, as in modern graffiti – put it down to a misspent youth and a love (despite appearances to the contrary) of Hip Hop – and I have followed BOOF’s career with a certain interest.

So here I shall leave it. Making marks, and marking time – it’s all about trying to achieve immortality, to leave your mark long after you are gone, and making people remember you, even if they don’t know who you are. I think that’s all any of us, myself included, can hope for. There are so many examples of this phenomena in the Glossop area, and I have an idea to produce a book looking at precisely this sort of thing – watch this space.

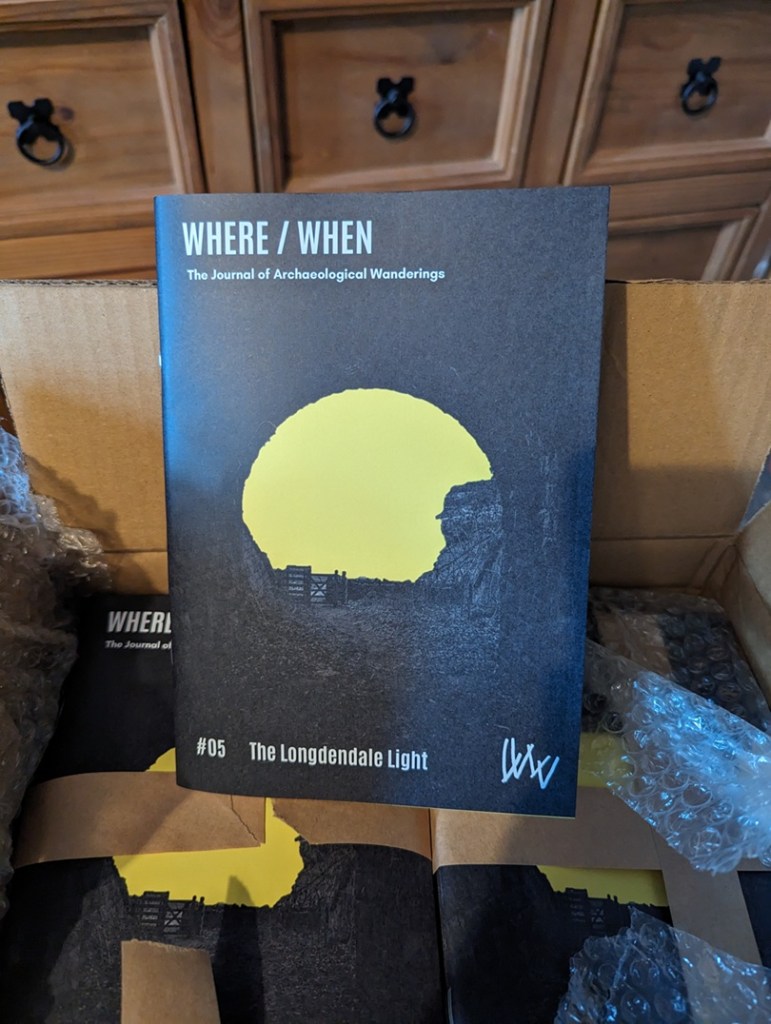

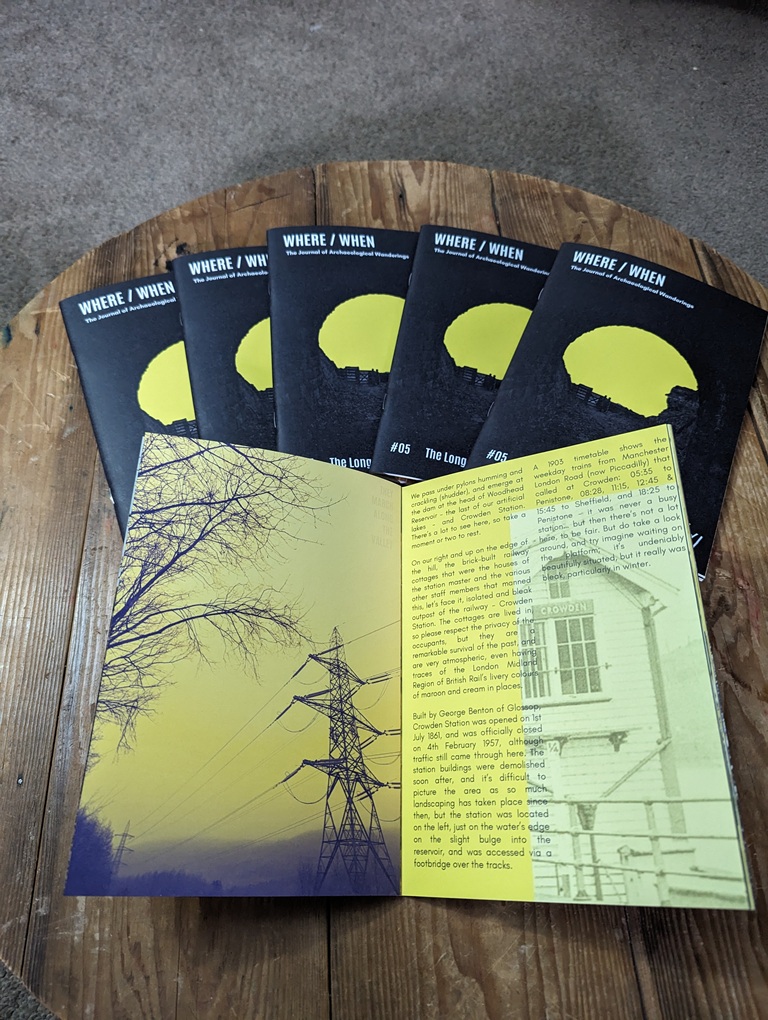

Talking of books, please check out Where/When Number 7 – Forts and Crosses: A Mellor Wander.

This one is a truly awesome Wander around Mellor – just over yonder! It has medieval field systems and farms, Victorian noise, an Iron Age hill fort, medieval crosses, cracking views, a terrifying viaduct, bench marks, a trig point, wonderful gateposts, and it starts and finishes at a pub… what’s not to love? Here’s the cover to tempt you.

Available from the shop, link above, or from Dark Peak Books and Gifts, High Street West, Glossop. Or, you know, just track me down and throw money at me.

Talking of which… if you enjoyed this, and fancy buying me a glass of the stuff that cheers, then please do so via this link to my Ko-Fi page. I do what I do here because I love doing it, and I feel it’s important we explore our shared heritage… but I’ll never say no to a pint in thanks!

So much more news to share, and so many things planned. Watch this space, wonderful people, as big things are coming.

But on a serious level, how are you doing? Genuine question. Personally, I’m a little down at the mo… the devastating loss of my brother (cheers Stephen, I’ll miss you), coupled with a dose of Covid, and the general malaise that accompanies the move from summer into autumn and winter, has meant a lull in the festivities here at CG Towers. Still, the wheel turns, the seasons they change, and life will inevitably continue, and on we go. But as I always say, look after yourselves and each other, you really are important, and too often we say “I’m aright” when we actually mean “I’m not alright, please help” – it’s ok to not be ok.

So then, more coming, but until next time, I remain.

Your humble servant,

TCG