So, a while back I went looking for the White Stone of Roe Cross… and failed miserably in my mission.

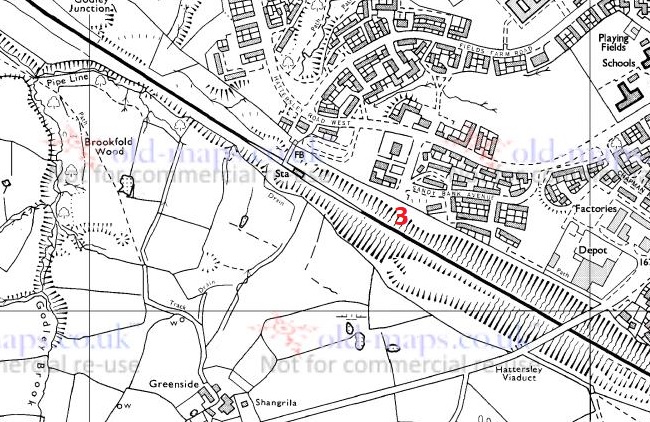

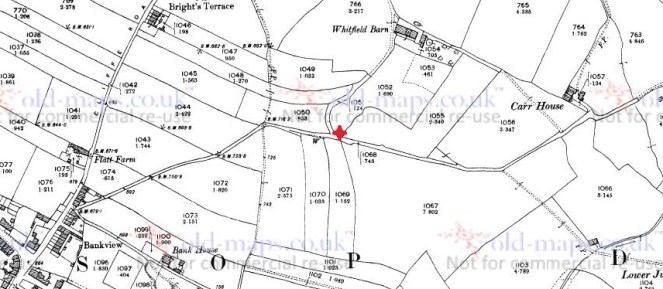

As I said here, it is mentioned in Sharpe’s book “Crosses of the Peak District” as potentially marking the junction of the boundaries of Matley, Hollingworth, and Mottram, so I thought it would be worth a look, and maybe make a comment on what, where, and why.

I did some digging (pun fully intended), and came up with very little; it has almost zero presence online (other than this letter), and other than a modern book (about more, later), virtually nothing but an oblique reference. I began to despair… until I started to dig a little further – my ‘spidey sense’ began to tingle. Summat wants fettling, thought I.

What I did come across time and again was a reference to the legend of Sir Ralph de Staley, and his relation to Roe Cross, and the Roe Cross. Now, the story of Sir Ralph de Staley (Staveley or Stavelegh or Staveleigh – there are numerous spellings), is a variant of “The Disguised Knight”, a story trope that can be traced back to at least Homer’s ‘Odyssey’. Our story, culled from several sources, runs like this.

With Richard I, Sir Ralph sets sail on a crusade leaving behind his wife, Elizabeth, and estate. By and by, and following many great battles, he is captured by the Saracens, and held for many years in a dungeon. Eventually, he gains his freedom, takes on the appearance of a Palmer (a pilgrim), and pays a visit to the pilgrimage sites in the Holy Land. One night, in Jerusalem, he had a prophetic dream “boding ill to his wife and home far away”, and so, invoking the intercession of the Virgin, he prayed and presently fell asleep.

Upon awakening, he immediately knew something was different – “before him, shining fair in the summer sunlight, rich in fulsome melody of singing birds, was a fair English landscape, and beyond it his own ancestral hall of Staley”. He had been miraculously transported home.

He set off for his house, and came upon a faithful old servant and his favourite dog, who presently recognised him. He told Sir Ralph that his wife, who had finally given up all hope and now believed him dead, was to be married the following day. So off he jogs to his hall, and asks to see the lady of the house. He is refused, but begs a drink of Methyglin (a type of spiced mead, apparently), and after draining the cup, pops his ring into it, and begs the maid to take it to her lady. She does, his wife recognises the ring as belonging to her husband, and asks an important question “if it be Sir Ralph himself, he will know of a certain mole on me, which is known to none but to him” (racy stuff, this). Of course, all ends well and happily, and the bounder that is trying to get Sir Ralph’s lands and his missus, is ejected rapidly into the night. And quite right, too.

So ends the story.

Now, here’s where it gets interesting. As a post script, most versions of the story (there are about 5, each with subtly different aspects) state that a cross was erected either where Sir Ralph meets the servant and dog, or where he wakes up following his miraculous movement. This is the Roe Cross – Ro, or Roe, apparently, being a shortened version of Ralph. Indeed, several sources mention a cross standing on the old road from Stalybridge to Mottram. But where is the cross? There is certainly not one there now, nor is there any evidence attesting to one. There is, however, the White Stone.

Ok, so here is what I think happened.

I don’t think there ever was a cross, not as such. None of the sources I consulted actually describes a cross, only that one was there (as told by the story and indicated by the name), or that there are the “remains of an ancient cross” on the road there (and thus presumably referring to the White Stone). It seems that the White Stone and the Roe Cross have become intertwined. Ralph Bernard Robinson, in his book ‘Longdendale: Historical and Descriptive Sketches‘ (1863) illustrates this perfectly by noting the existence of both cross and stone as separate monuments, but he only describes the stone, not the cross. I would argue that it doesn’t/didn’t exist.

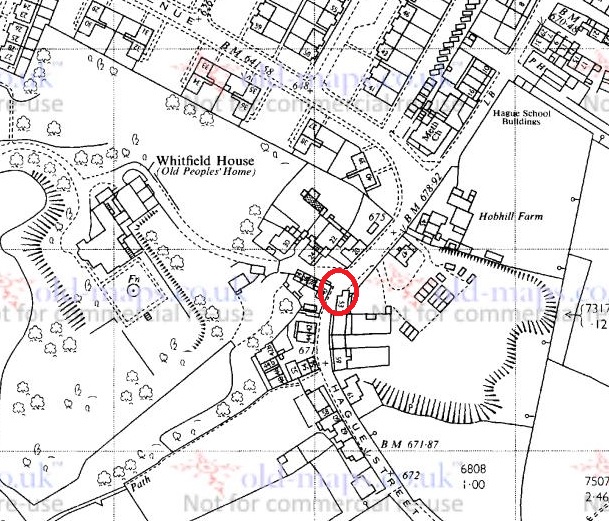

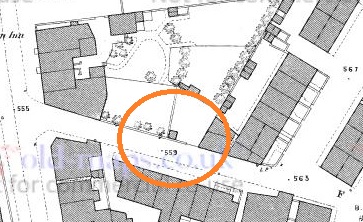

It is most likely the name Roe Cross is derived from ‘roads cross’; the area is, after all, the junction of seven roads – Harrop Edge Road, Matley Lane, Gallowsclough Road, Mottram Road (Old Road), Hobson Moor Road and Dewsnap Lane. Indeed, according to Dodgson’s Place Names of Cheshire (Vol.1, p.315), there seems to be no reference to Roe Cross prior to 1785 (although this may turn out to be incorrect, with further research).

So far, so good… now bear with me. The White Stone is a marker stone, marking tracks over the tops, and/or marking the boundaries of Matley, Stalybridge, and Hollingworth, and it has been there from the year dot. As a feature in the landscape, it was given a story, as all such features are – they accumulate stories, because people have an intrinsic need to have a relationship with their environment – and it takes on a personality, and gains a biography. As the archaeologist Richard Bradley says of monuments “they dominate the landscape of later generations so completely, that they impose themselves on their consciousness”. The story of Sir Ralph (whether ‘true’ or not) was given as a way of explaining both name – Roe Cross – and reason for the existence of the marker stone. In fact, in Ralph Bernard Robinson’s account of the legend, Sir Ralph wakes up “beside a large stone”, and later on notes that “tradition points out the stone under which he found himself laid: and a queer old stone it is.” Clearly he is describing this from his own personal experience, and surely there can be only one stone that is worth pointing out in the Roe Cross area… it has to be The White Stone.

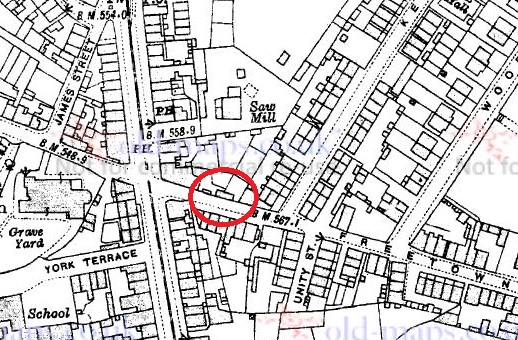

As a postscript to the postscript, Sir Ralph and his wife, Lady Elizabeth Stayley, are supposedly buried in St Michael and All Angel’s church, Mottram. There are two 15th Century carved effigies that are to be found in the Stayley Chapel there, which almost certainly are meant to represent the good knight and his wife, and which were originally placed against the south wall of the chapel. As Aikin in his ‘Description of the Country Thirty to Forty Miles Round Manchester’ (1795) notes, “many fabulous stories concerning them are handed down by tradition among the inhabitants”.

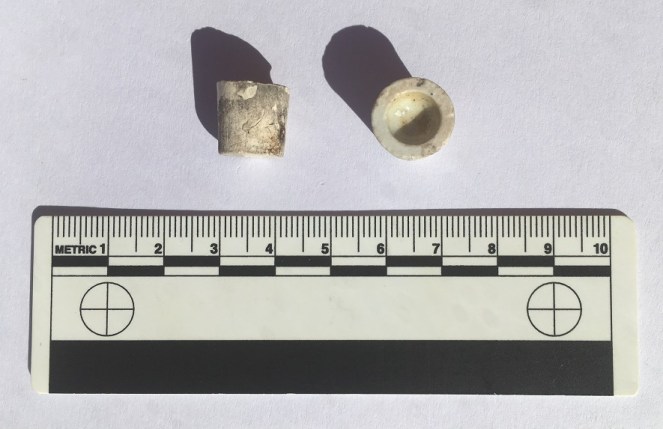

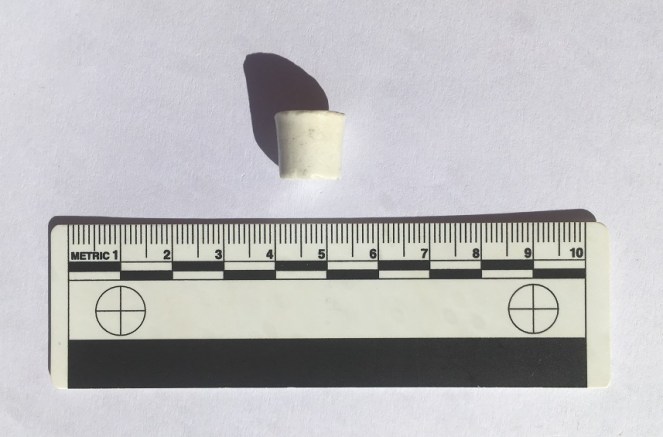

So then, the White Stone. Well, I still haven’t found it! But I do know a bit more about it, and now – drum roll please – I have a photograph of the bloody thing, stolen shamelessly from Keith Warrender’s book ‘Manchester Oddities‘. I heartily recommend this book, as it’s chock full of just the sort of odd bits of history that this blog looks at. Buy it here. Or better yet, order and buy it from Bay Tree Books – buy local and keep independent shops afloat.

So here is the offending stone, in whose shade, Sir Ralph found himself transported from the holy land.

The reason for it being white is presumably to make it stand out, to ensure this important stone (boundary marker, track marker, or teleportation stone) is kept vividly different from any other in the area. Apparently it’s now on private property, which would explain why I couldn’t find it last time I went looking for it. I’m not sure of its exact location, but somewhere in the vicinity of White Stone Cottage would seem to make sense. Here is the drawing in Sharpe’s ‘Crosses of the Peak District‘.

I love it when a legend has a physical mark in the landscape, it makes it more real, and as I say, it is a natural instinct in humans to build stories around their places. I recently led a guided archaeological tour of Alderley Edge, which looked at the Legend of the Wizard through an archaeological lens, and this same element, on a smaller scale, was at play here. Place and story working together, informing and shaping each other.

Apologies for the slightly rambling nature of this blog post, but I hope you enjoyed it.

As always, comments and questions are most welcome.

Your humble servant,

RH