I love that word… but more about it in a bit.

I went for a walk with some friends a few weeks ago, from Old Glossop to the New Lamp pub in Hadfield, via Valehouse Reservoir and the Longdendale Trail. It runs along the old Woodhead Line train track there from Hadfield Station to the Woodhead Tunnel entrance. All the way along it you can see evidence of its former existence – signal cable carriers, track equipment, assorted bits and pieces, and bridges.

As I passed under one bridge (the Padfield Main Road) I glanced up and saw this.

well, more specifically, this bit.

High up and hidden amongst the stonework were a number of mason’s marks. Awesome, thought I.

It’s here on the map.

Mason’s marks are a really fascinating aspect of stone masonry. Essentially, the stone masons were paid by the piece – the more they carved, the more they got paid, and in order to make sure they they got paid for the correct number of stones worked on, each mason signed their piece with their individual mark. It also acted as a form of quality control – if a piece of stone was not up to scratch, the master mason could see at a glance who carved it. This concept of signing your work had been going on since the Medieval period, and continues to this day. It’s not often you get to see them, as more often than not they are on the reverse of the stone, hidden within the fabric of the building. But here, for some reason, a group of masons (I count three different marks, but with perhaps another three possibles) decided to display their signs. Still, nice to see these out in the open.

Imagine my surprise, then, when we decided to go through an underpass, underneath the old track bed, and head down to the reservoir at this location, here:

Wow… just wow. A grotto of mason’s marks. Quite literally, every stone was covered in mason’s marks, all of them. Outside and inside… amazing.

It is wonderful!

Now, I’m not sure why there is this cluster of marks on this specific underpass. Perhaps they were allowed to go wild and leave their marks in the open in this one place. Or perhaps, there was a competition between two rival gangs of stonemasons, each working to complete the stones fastest. I simply don’t know.

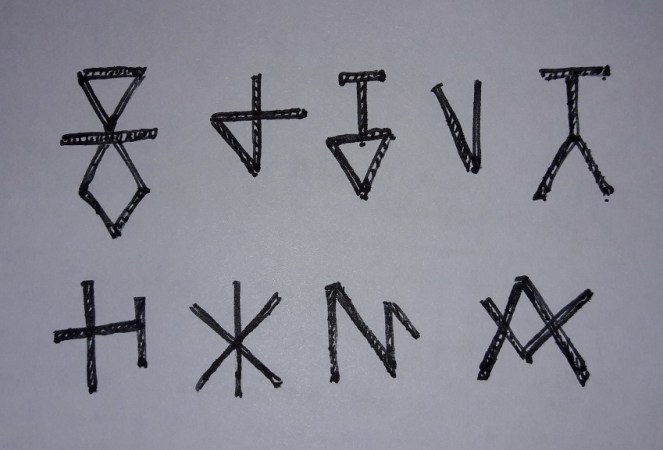

I have made a list of the mason’s marks.

The mark bottom right is probably a square and compass symbol – both tools are used by stone masons. It is also a symbol used in Freemasonry, which takes a lot of its signs and symbols from stonemasonry.

It would be interesting to compare them with others on the Longdendale line, to see where else these men were working here. Also, as they would be itinerant stone masons, travelling where the work is, we could compare them with others further afield. After all they are a signature, and whilst we may not know their names as such, they left their mark on our landscape. They don’t seem to match those on the bridge, though it’s difficult to make out. There have been attempts to create a database of masons marks, particularly those from the medieval period in the catherdrals. However, whilst at first glance this seems a great idea, there is flaw in the plan: there are a finite number of marks you can make with a chisel and using only straight lines. It was found that many marks were reused by different masons, sometimes separated by centuries. There is something deeply interesting about mason’s marks, though, and some are more interesting than others… Looking back at the bridge mark, I was struck immediately by the ‘M’ mark.

Apotropaia. From the Greek, apotropos, meaning literally ‘to turn away’, and more specifically in this case, to turn away or prevent evil.

People have always used signs and symbols to act as magic charms to stop bad things, and bad people, from affecting them. Apotropaic marks became very common in the 16th-18th centuries, and any domestic dwelling of the period would have had these marks carved literally into the frame of the house. At this time, the reality of evil was not questioned, and people intent on causing you damage and sickness – witches – were a real threat and believed in utterly. Indeed, the marks are sometimes referred to as “witch marks”, and have only recently begun to be researched. I can almost guarantee that any timber framed house from the period will contain at least a few. Often they are placed by windows, doors, and fireplaces – essentially, any opening, anywhere that a witch, ghost, devil, or other evil thing might gain access to the house. The marks take many different forms, but two of the most common are the ‘daisy wheel‘ mark – usually carved into stone or wood with a compass…

…and the ‘double V’ sign. This latter is very interesting; it is largely understood as standing for ‘Virgo Virginum’ – the Virgin of Virgins, or the Virgin Mary, and may be seen as a plea for her help.

Now, given that the marks are occurring at a time when it was illegal and/or extremely dangerous to be a Catholic, it is unclear what is happening here. Either we are seeing an underground following of Roman Catholicism amongst the population, which is very unlikely. Or more probably, it represents a popular belief or superstition that, whilst nodding to the Virgin Mary, is just understood as a protective symbol, without the trappings of Catholicism that would mean you were burnt at the stake. Essentially, by the 1600’s, people no longer understood the more religious meaning of the symbol, but carried on the use of it as a form of protection.

As further evidence of this, it is often found inverted, as an ‘M’, not a ‘W’. The letters are not important, the shape of the lines is.

Which brings us back to the bridge mason’s mark

Is the mason: a) A catholic, proclaiming his faith, and marking his work thus? b) Aware of the ‘good luck’ aspect of the sign, but has no idea of its origins? c) A mason who is using it solely as his mark, with no understanding of the meaning beyond its shape?

Personally, I’m going with b, but with a small dash of c.

There is so much more to be said about this subject, it is really a genuinely remarkable field of research (and one in which I am involved), and as it is just emerging as worth studying, I urge all of you to keep an eye out for any marks on buildings, especially internally, and particularly if they are built before 1850.

Right, I have a glass of wine waiting for me, so cheers. And next time, I think some more pottery is in order. Oh, and apologies for the long post, again.

RH

Very interesting, thanks!

LikeLike