I went for a pint with my father in law a few weeks ago (hello Mr B!) in what has become a bit of a Wednesday evening post-work ritual for us. We popped to the Prince of Wales in Milltown which, I am reliably informed, was built in 1852. And an excellent pub it is too – good beer, and a great beer garden. It has a real sense of history about it, especially as the area is now being developed so heavily, and I would imagine that it would have been a bustling pub, rowdy and rough, in the 1800’s.

Sitting drinking my beer and chatting, I had a look around to see if I could see anything of interest, and lo! In the flower bed amongst some more modern glass and pottery, were these beauties:

I love clay pipes, I really do. There is something so tactile about them, and so personal too. I joke about them being the cigarette butt of the Victorian period, and they are in a sense – smoke them and then throw them away – but they embody so much more. Believe it or not, they are the subject of many very detailed archaeological studies; they are mass produced, but they show features that shift over time, allowing a fairly precise date to be given to the pipe, and possibly then to the site/building/feature. Google “clay pipe chronologies” for examples. I’m not going to go into too much detail, as I really am no expert, but these two examples are very obviously Victorian. The bit on the right is part of the stem, and comes from near the mouth-piece, as the stem get thicker nearer the bowl. The piece on the left has the stem, spur (that little bit the points downwards), and the lower part of the bowl, where the tobacco itself sits, and which in this case shows signs of burning. Neither are particularly interesting, and they are certainly not rare, but nevertheless are integral to the human story of Glossop, and one wonders what conversations were happening in the pub whilst they were being smoked?

The history of The Prince of Wales, and all other pubs of Glossop, past and present, are detailed in the excellent book ‘History in a Pint Pot’ by David Field. Meticulously researched and fascinating, it is highly recommended to anyone with an interest in the history of Glossop, pubs, or beer – so that’s all boxes ticked for me. It is now out of print, sadly, but Glossop library has a copy. You could also check out the superb Glossop Victorian Architectural Heritage website, they have lots of information about pubs, and much more besides. Well worth a look.

Moing on, this next pipe is a bit more interesting.

I found it a while back on the edge of my favourite path – Bank Street, or the ‘Bonk‘ as it’s known locally. However, not being born in Glossop, I would feel a fraud calling it the ‘Bonk‘, so Bank Street it is.

I love dialect words and phrases – the way that the beauty of the English language is tied firmly and absolutely to the place it is spoken is truly remarkable. American friends of mine marvel at how many accents there are in such a small island. And yet if we go back 100 or so years to a period before mass media, it would have been possible to tell not only which town you came from, but which part of the town, and indeed which street you lived on. Now that we are bombarded with accents and the media is dominated with southern ‘Estuarine‘ English, we are slowly becoming linguistically homogeneous and eventually we may lose our accents altogether, which I think would be a shame. What is interesting about ‘Bonk‘ as a word is that it not only partly reflects the Glossop accent, but it is also almost certainly derived from the medieval French ‘Banque‘ meaning a steep wooded valley next to a stream. It crops up in Cheshire dialect as ‘Bongs’, and the nearest examples I can think of is Leebangs Rocks in Broadbottom (Leebangs = Le Banques), and The Bongs both in Handforth, and in Goostrey. It’s not often you encounter Norman French in Glossop!

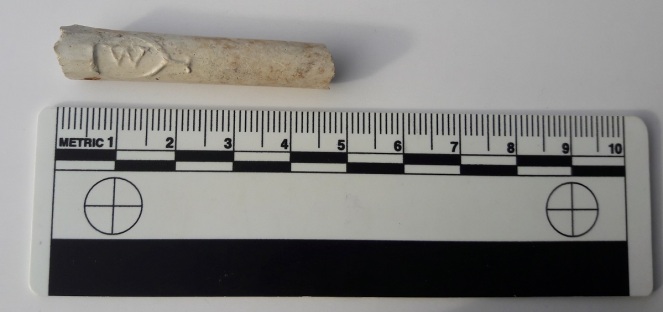

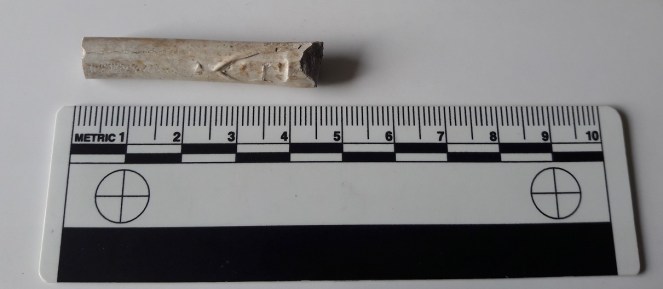

But I digress! It was found not too far from the bottle top I blogged about here. I thought it nothing particularly special until I got home and cleaned it. Wow!

It’s the front part of a clay pipe, just at the point where the stem meets the bowl – you can see it thickening into the bowl. But on either side, imprinted into it, is a cartouche containing the letter ‘T’ and letter ‘W’. Presumably these are maker’s marks, but unfortunately, I cannot find any information out about who or what ‘W’ and ‘T’ were. Also there is the suspicion that they may actually not be maker’s marks as such, but were instead used by many different companies as a way of suggesting quality – it was perceived by the buying public that those letters were associated with a superior pipe (I read this somewhere, and now can’t find the reference… grrrrrrr). This would be similar to the Victorian belief that pipes from Ireland were the best, and thus many clay pipes have the words ‘Dublin’ or ‘Ireland’, or have a harp or shamrock imprinted on them somewhere… despite being made in Birmingham or similar. It is Victorian in date, and scrubbed up quite nicely!

I was originally going to blog about this in a larger post about the trip down Bank Street (which I will still write… honest!), but it seemed to fit in here better.

By the way, if the landlord of the Prince of Wales reads this and wants the pipes back, I’ll bring them round next Wednesday!

EDIT I found the reference to ‘TW’ – it was in the Clay Tobacco Pipes report by Dennis Gallagher, and from the High Morlaggan Project (the report is under excavation / reports / clay pipes). In it, it states that ‘TW’ pipes “were an extremely popular type and were produced by most makers. The meaning of the letters is unknown, although it may originally been used by the early 19th century Edinburgh maker, Thomas White, who was renowned for his high quality pipes“.

So there you go.

RH

2 thoughts on “Pipes, Lovely Pipes!”