What ho, wonderful blog reading folk! I trust the Autumn is going well for you all? And hopefully, now that restrictions have eased, we will be able to do a bit more.

A fascinating one this time – well I think so. There’s a place, if you know where to look… Oh, go on then, I’ll tell you.

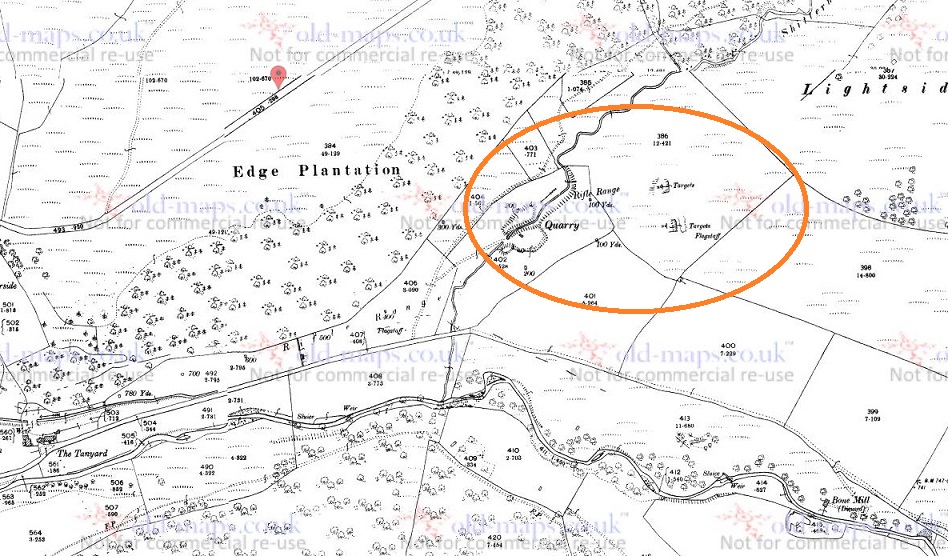

At Mossy Lea, to the north west of Shire Hill, there is a Victorian rifle range marked on the map. “Hmm” thought I, “I wonder what is there?” It turns out that it is a thoroughly interesting place, chock full of history. Here it is on the map:

But why was it there? Well, following the Crimean War (1853-56), and amid rumblings in Europe, particularly between France and Austria, it became clear Britain needed a larger, more efficient, armed force. In 1859 the decision was taken to boost home defence and operational forces with the creation of the volunteer rifle corps. The forerunner to our Territorial Army, these ‘part-time’ soldiers could be called upon to fight should the need arise.

It was desired that Glossop should have its own corps, and so in this way, on June 14th 1875, 23rd Derbyshire Rifle Volunteers was formed, with the first inspection of the corps taking place July 29th, 1876, at Stockport. They were drilled frequently, just like the regular army, with a parade ground off Shepley Street in Old Glossop, and a drill hall in the market hall – the entrance nearest to the post office.

And of course they trained frequently on the rifle range. The original rifle range was at Chunal – probably around what was once The Grouse pub (now a private house). Hamnett notes that it was “most inconvenient” as the men had to shoot over the highway when shooting at long range, which was causing delays. Yes, you read that correctly… now let it sink in a moment.

Shooting. Actual bullets. Over a public road.

So “for the safety of the public it was removed to Mossy Lea“. You don’t say. Shooting here commenced on 6th June 1877, and it is then that we join it. The original line of the range was shooting at targets against Shire Hill, as seen in this 1880 map:

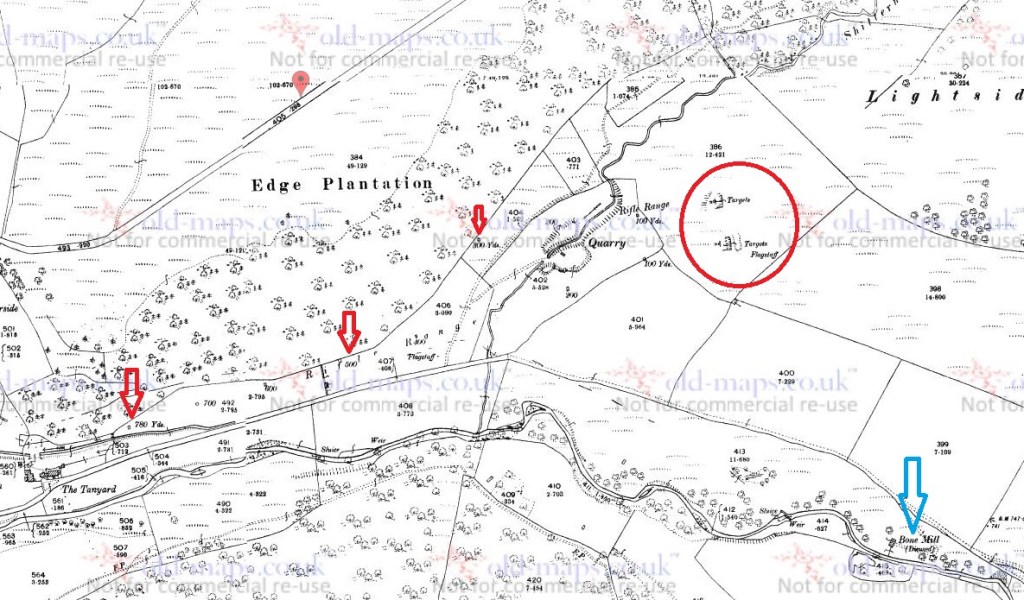

By the time the 1898 map was drawn, the targets had moved to Lightside, with shooting platforms along Shepley Street, here:

However, whichever direction you shot, it seemed to have been hard work, as Hamnett notes “It is a most difficult range… owing to the various strengths of the winds we get all blowing at the same time”. Anyone who has walked along Shepley Street and Doctor’s Gate will know what he is talking about.

So me being me, I decided to have a look around to see what, if anything could be seen on the ground. As it happens, it turns out quite a lot.

Both targets are visible on the ground, and are essentially huge pieces of metal sitting on top of platform. Closer inspection shows it is very interesting.

Walking around the back of the target, I noticed some writing… ooooh, says I.

Now, with the eye of faith and if you squint after a snifter or three, I can just make out the following words:

“WOODS’ UNIVERSAL – unclear – TARGET. WOODS COCKSEDGE & CO. STOWMARKET. 1876”

Nice! And it even gives a date, which is unusual in archaeology to say the least. There is a little bit about Woods, Cocksedge & Company here (and no sniggering… honestly! Don’t think I can’t hear you. I’ll have you know this is a serious blog), with more dotted about the internet. They seem to have been a standard iron foundry, founded in 1812 in Stowmarket, Suffolk, and which continues in one form or another until the early 20th century, perhaps even beyond. Research on the internet produced this advert, stolen as always, shamelessly, from this website.

The targets in the picture are clearly the same as the ones on the hillside – they have the same attachments, and you can see how they were fitted and braced when in use.

The advert is full of additional details – such as the fact that these were made from hematite iron (rather than wrought iron) (is the missing word on the target “hematite”?), and that Woods, Cocksedge & co. were supplying the government with their targets. I note also that they were supplying “nearly every foreign power”. I’m sure it was comforting for our soldiers to know that, as the bullets pinged around them, the reason that the foreign soldiers trying to kill them were so accurate in their shooting is that they were trained on the same targets as them.

It also states that the targets are “indestructible”, and they seemingly pretty much are – 150 years later, and I’m certain they would withstand modern rifle shot. Probably.

There were also some small finds – unsurprisingly, a number of bullets.

What is interesting, though, is that these plot the history of British Army issued rifles from 1877 onwards. The militia were originally issued Snider-Enfield rifles, but these were used only on the original Chunal range, so we have no bullets from these. We know that in 1877, they were using the Martini-Henry rifles, and our earliest evidence is, then, on the left, the large lead slug of a Martini-Henry rifle – you’d know about it if one of those hit you. These bullets are interesting from a design point of view – they have a slightly hollow base that expands with the explosion of gunpowder behind it, connects with the grooves inside the rifle which, combined with its solid weight, makes it more accurate and very powerful.

Next, the Lee-Metford copper jacketed .303 round, which the company were issued on 18th September 1897, and which was responsible for these targets being installed. As Hamnett puts it “the greater velocity of the bullet of the new rifle made the old iron targets unsafe”, and they were replaced by the Woods’ Universal Hematite targets. So we have a date for their installation – sometime after September 1897, and I assume at this point the targets were moved from against Shire Hill to where we find them today. Next to the bullet is the copper jacketing which is formed around the lead bullet – you can see how it has peeled away, and imagine the effect that the peeling and tiny razor sharp fragments would have if you were shot. It’s sometimes easy to forget that these small interesting lumps of metal were designed and made with just one purpose in mind – to create a large hole inside another human being.

Next to that is a standard early 20th century Lee-Enfield .303 round, and probably owes its occurrence at the range due to live-fire exercises carried out hereabouts in 1943 by a unit of commandoes. Neville Sharpe in Glossop Remembered (p.154) recalls the commandoes showing the local boys how to extract the cordite explosive inside cartridges to make fireworks… with predictable results. I also like the continuation of use, as though the land once used in a particular way somehow lends itself to that particular activity. The area is now home to the Old Glossop Clay Shooting Ground, and the hills once more ring with the sound of gunfire. They claim that the area was in use for shooting from the Second World War onwards, but we now know differently.

The path up to the targets also produced a few pieces of pottery:

From the left, then: An Annular or Banded Ware rim sherd of a smallish jug (the diameter is 8cm, but curves inwardly slightly). Date wise, it’s probably late 19th century, so about the right date; I love this stuff. Two pipe stems, also of a similar date (I like to imagine them being smoked by bored soldiers wending their way up to the targets). And finally, a sherd of Transfer Printed pottery, which could date from anytime after 1840, but is probably the same date as everything else.

Hope you have enjoyed this jaunt down the military history of Glossop – the story of the militia is told in Hamnett’s History of Glossop, a copy of which is in the library, and it highly recommended. The range itself is on public access land, and right by a footpath, so go ahead and have a look (it’s a great place to fly a kite). But please don’t go digging around there – not only is lead highly toxic, without the landowner’s permission it is illegal. Plus, all you’ll find is lumps of twisted metal. The finds I made were lying on the surface.

My thanks for the company of Andy T on this particular jaunt – he’s a good bloke, mostly, and can be found on Twitter @Thorny61.

Please feel free to email me with comments and questions, even to point out that I am wrong about something. Until next time then, look after yourselves and each other.

Until then, I remain.

Your humble servant.

RH.