What ho! Come in, come in. May I take your coat? Perhaps a glass of the stuff that cheers? Red? White? There is some fizz open, too. Now take a seat for Part 9 of the Rough Guide to Pottery. I know, I know, I can feel your excitement from this side of the screen.

So what, then, is today’s offering? Well, quite frankly… Stoneware.

This is a bit of an odd entry, to be honest, and truthfully this is a sort of catch-all grouping, rather than a coherent ware type as is the case with other entries in the series; essentially, it covers all stoneware vessels regardless of glaze type or decoration. We’ve covered stonewares before (Brown Stoneware and white stoneware and associated types), but this one looks at everything else (look, it’s no use screaming “for the love of Zeus, spare us” no one is asking you to read the site, you know).

So then what do we mean. Stoneware is regular earthernware that is fired to a higher temperature (roughly 1200-1250 degrees, as opposed to 600-1000 degrees with regular pottery). This means it vitrifies – or melts – and produces a very hard wearing and watertight pottery which is perfectly suited for all manner of uses, from cooking and storage, to serving and drinking.

Stoneware has a characteristic pale grey/creamy coloured fabric, which is extremely hard and often with tiny visible voids in it, produced by gases during the firing process.

It also produces a sort of metallic ‘tink’ when tapped with another sherd, as opposed to the duller ‘thunk’ of regular pottery (but the ‘tink’ is not as high as that made by porcelain… don’t look at me like that, I know what I mean).

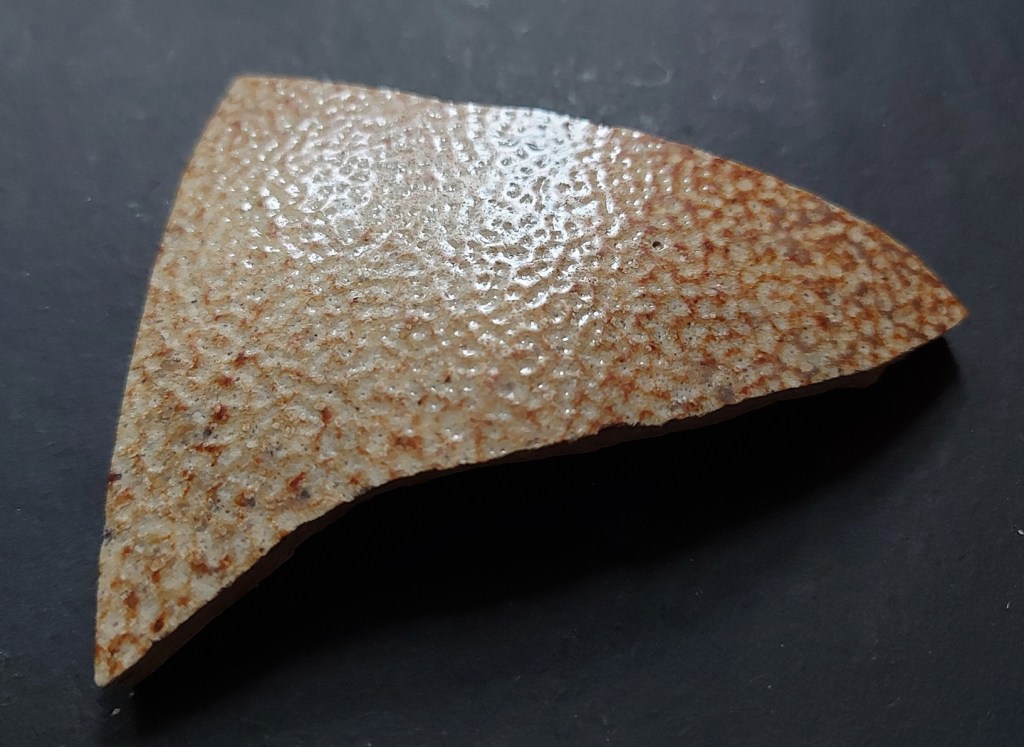

Now, although technically it doesn’t need a glaze, one is usually applied for decorative purposes, and to provide a smooth surface. However, most glazes wouldn’t survive the heat needed to produce stoneware, so early Stonewares used a salt based glaze. In this method salt is added to the kiln, which vaporises into the atmosphere inside coating the vessel. The sodium oxide in the salt reacts with the silica in the clay producing the characteristic ‘orange peel’ surface which is particularly associated with early forms of salt glaze pottery.

The salt glaze is naturally a creamy light brown colour – honey and mustard are words often used – although when other chemicals are added, this can change (the iron rich salt-glaze in the Nottingham/Derbyshire stonewares, to name an example we have seen before). Vessel forms associated with the earlier salt-glazed stonewares are bottles – some of which could be quite large – mugs, and jugs. Perhaps the most famous type is the Bartmann, or Bellarmine, jug:

the Bartmann (German ‘Bearded Man’) was produced in the Colgne area of what is now Germany in the 16th – 18th centuries, and were exported all over Europe, containing wine and other liquids. They were imported into Britain in huge quantities, and are relatively common in the London/south area, but much rarer up north. Their characteristic bearded face give them a sort of human-like appearance – a man with a large belly – hence their other name of Bellarmine Jars, after the portly Cardinal Bellarmine. I am almost certain that my favourite sherd above comes from a Bartmann… or is that wishful thinking?

It is this human-like appearance that may account for their popularity as ‘witch bottles’ as a form of sympathetic counter-magical protection very popular in the 17th century (although examples exist of ‘witch bottles being made in the early 20th century). If you suspected that you were being cursed by a witch, you took one of these bottles – symbolically representing the witch, and in particular their bladder – and fill it with urine, nails, metal pieces, broken glass, hair, and other assorted unpleasant objects; stopper it, and then gently heat it in front of a fire. The idea being that this would cause the witch intense pain in the bladder, causing them stop cursing you. Depending on the need, the bottle could also be buried, particularly beneath the hearth, so that the pain continues. Unpleasantly, there is at least one instance on record of a death caused by the bottle exploding – a sort of stoneware hand grenade. As an aside, Magical household protection and counter magic in the Glossop area really needs its own article, as I have a whole pile of evidence for such practices. Hmmm… let me see what I can do.

By mid to late 18th century, and probably connected with the increased use of coal-fired kilns, the surface of salt-glazed stonewares begins to smooth out – a useful rough dating tool for sherds – the rougher the orange-peel, the earlier the bottle… or something like that.

Around 1835 a new, no salt-based glaze was developed – the Bristol Glaze. My notes inform me that this is technically a “feldspathic glaze slip using zinc oxide“, and I for one am not going to argue with that. This produced a much smoother and more consistent surface, and was widely adopted. This is most characteristically found in a two-tone version, with the upper part of a bottle being a mustard colour, with the lower a pale grey or cream.

There is something aesthetically pleasing about these bottles, and they have a sort of gentle nostalgic feel about them, which is odd because they stopped being manufactured at the turn of the 20th century when glass bottles became the norm. Again, a useful dating method – not a hard rule, more of a gentle indication.

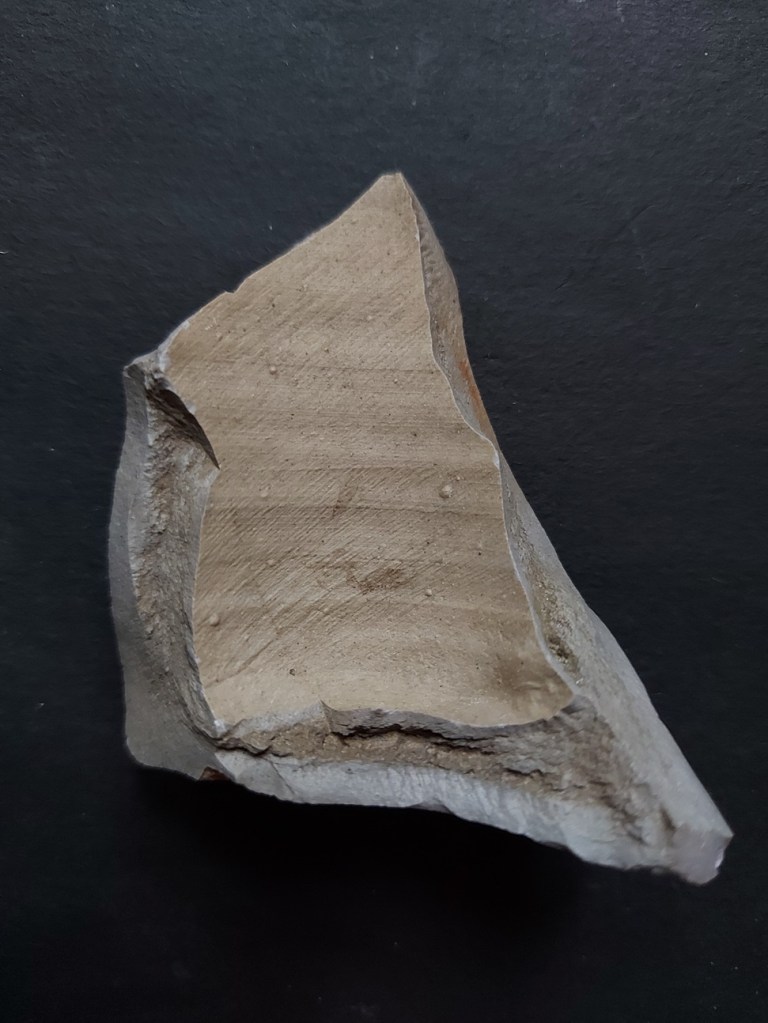

The Victorian period saw a huge explosion in the production of stoneware, and in particular bottles which were, remarkably, all hand made on a wheel. If you find a broken bottle, look carefully at the interior; you can normally find pulling marks, where the potter has formed it using their hands, and the base frequently has circular marks from when the finished bottle was cut from the wheel using a string whilst it was still turning.

This photo of the bottle interior really illustrates how the bottle was made. Not only can you see the large horizontal ribs made by the potter’s fingers as he draws up the clay to form the shape, but you can see wiping marks running diagonally, formed as the potter used a cloth to smooth the interior. Once the bottle is finished, it was cut from the wheel using a string or wire, which usually leaves characteristic marks:

The wire is drawn toward the potter who would have been sat to the upper right in this photo – the ‘U’ shaped marks pointing toward them. But note also the slight wobble in the ‘U’ shape, produced because the wheel was still moving slightly; speed is of the essence here, as the potters would have been paid for the number of bottles made.

I love this, not only does it provide us a view of how the bottle was made, but it really gives a connection to a long dead human, a real person amidst the industrialised chaos. I read somewhere of celebratory bottles marking the occasion of a potter’s millionth bottle being made, which gives you an indication of the scale of the bottle making industry.

On bottles, the name of the bottle manufacturer is often found impressed into the clay, usually near the base.

The name and logo of the company, as well as the contents, are much larger, and were originally impressed into the body.

After about 1880 (ish), the development of high temperature resistant transfer printing meant that information and designs could be clearly printed on the side.

Common are ginger beer bottles (though truthfully, they contained all manner of drinks), blacking bottles, containing blacking for ovens, and which are, oddly enough, normally white in colour. Also cream pots, milk bottles, and large flagons of cider or chemicals.

Ink bottles, too, and in particular the ‘penny ink’ bottles are common. Also known as pork pie inks, as they are the same shape and size of said savoury delicacy, and cost how much… that’s right, a penny.

Always check the exterior of any sherds you find, as often they have finger marks on the exterior, from where the wet glazed and pre-fired pot was put on a rack to dry. Often, soberingly, the finger marks are very small, an illustration of the child labour that underpinned the industrial boom of the Victorian period.

Right then, I think that’s all I have for Victorian Stonewares, and honestly that is about all we need – it’s very recognisable, but it’s good to have a little context. I know I’ve said it before, but I’d really like to try my hand at potting, perhaps reviving some of the older 17th and early 18th century shapes of cups, mugs, plates; I’ll add that to the list of retirement plans!

So then, other news.

I’m planning a new Wander, this one involving lots of medieval bits and pieces, and a merry jaunt from Whitfield to Old Glossop, and back. It will form the basis of two future issues of Where/When… when I get round to writing them up. But before that can happen, it needs a test-drive, so to speak. Keep an eye open here, on twitter, or simply “what ho!” me in the street. I’ll put it on Eventbrite, too, so I can keep an eye on the numbers. I’m excited about this one, so watch this space, and let me know if you fancy it.

The first issue of the Where/When ‘zine is still available, only £5 and available at Dark Peak Books, or seek me out. A free PDF is available, too – click on the tab at the top of the site.

I’ve got a lot of big ideas and collaborations that might come to fruition. Might. But again, watch this space. And do stay in touch… It’s nice to know that all 6 of you are ok! Expect another post soon, too… I’m aiming for two in February. Aiming…

So then, until next time, look after yourselves and each other, and I remain.

Your humble servant,

TCG