What Ho! What Ho! And if I may be so bold… What Ho!

How are we all? Bearing up under the circumstances? Summer, such as it was, has gone, and Autumn is upon us. A time of harvesting, of blackberrying, of apples… and pottery, obviously. And just like that, without further ado (and ignoring the groaning and wailing and gnashing of teeth), we tiptoe into Part 8 of the fabled (and seemingly never-ending) Rough Guide to Pottery; let’s have a look at some rather splendid sherds.

So then, today we are looking at some rarer types of pottery – well, perhaps not rare as such, just not as commonly encountered as some of the other stuff I’ve previously talked about.

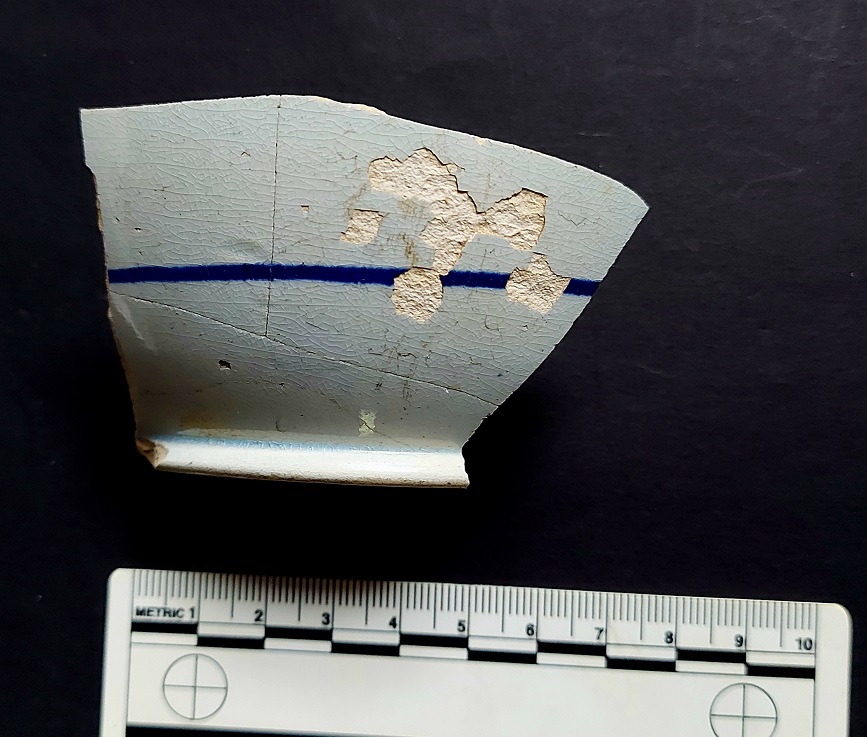

TIN-GLAZED EARTHENWARE (aka Delft)

DATE: 1650-1770

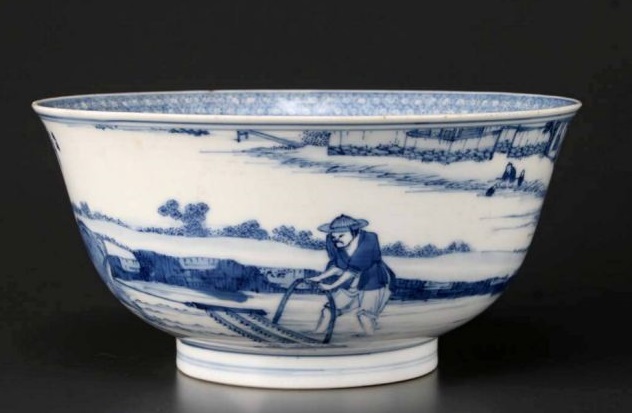

DESCRIPTION: Hand painted glazed blued decoration on a whitish/blueish background

SHAPES: Cups, saucers, bowls, plates, small jugs, tankards, chargers with prominent ring foot. fine and delicate, with thin walls. Decorative tiles were also common in wealthy houses.

Originally tin-glazed pottery was imported from Italy, Spain and the Low Countries, but UK production began in Norwich in late 16th Century. Its heyday was roughly 1700 to say 1800… roughly. It remained popular until it was gradually replaced by White Salt-Glazed Stoneware by the mid 18th Century, which was more robust and much lighter, and cheaper to make. Tin-glazed pottery was another attempt at reproducing porcelain type pottery, and part of the quest to find a pure white background that seems to have dominated pottery making in the 17th and 18th centuries.

The process of manufacture was as follows. The vessel was turned by hand and using a former, and then biscuit fired (that is, it was fired undecorated and without a glaze). The pot is then dipped in the glaze and allowed to air dry. Once dry, the pot is then decorated by hand – quickly as the glaze is very absorbent. It is then once again fired, which fuses the glaze and fixes the decoration.

In terms of fabric, it’s an earthenware, a pale colour – white-ish or cream colour, with later examples being almost pure white. It has occasional tiny pink, reddish or darker inclusions, and is a soft to medium hardness.

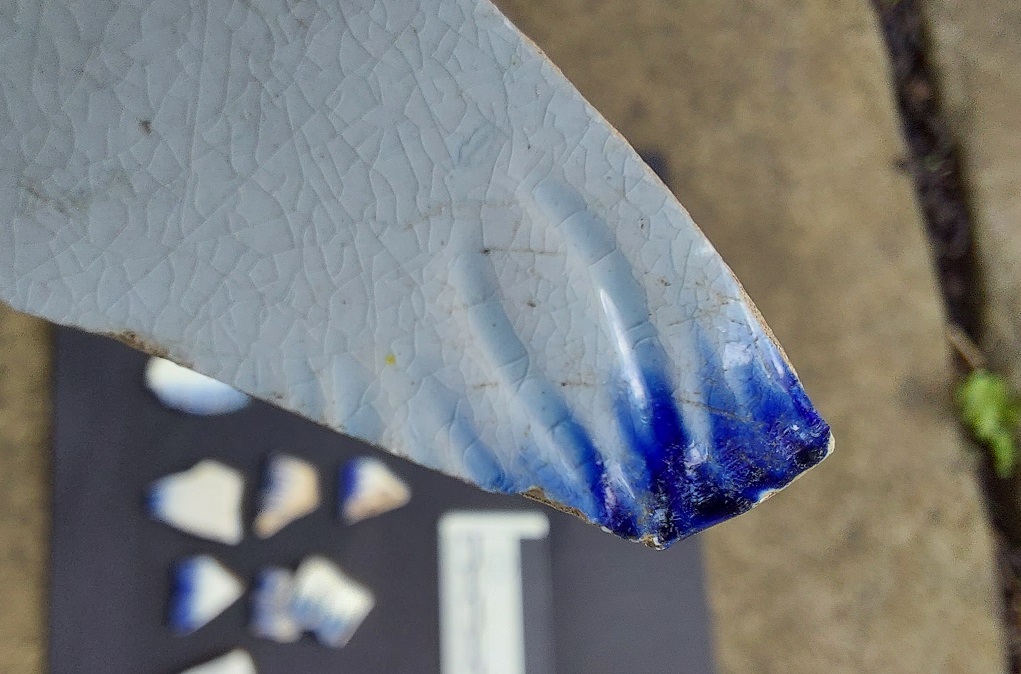

It uses a lead oxide glaze mixed with tin, which gives it a blueish white or pale cream colour, but is more blue where it pools – in particular around the ring base, where the pot was dried upside down.

The glaze has an almost luminescent quality and has a consistent smooth, dense feel to it – the product of the lead – but can occasionally have tiny imperfections or dimples in it. The glaze can also be thickish in places, but it is fragile and can flake off in patches, exposing the fabric below – most obviously at the edges of sherds. The surface occasionally shows the marks of the trivets that separated the vessels in the kiln.

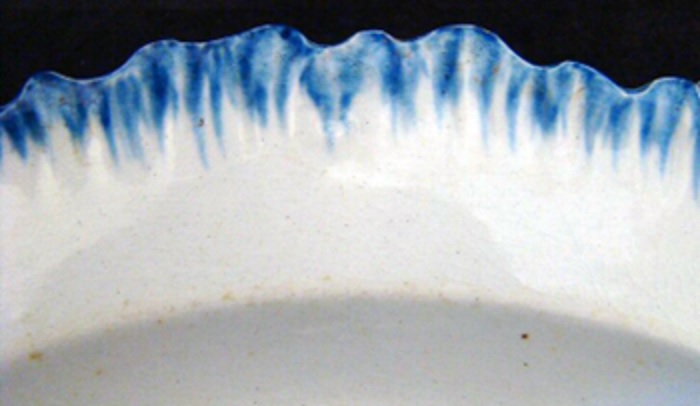

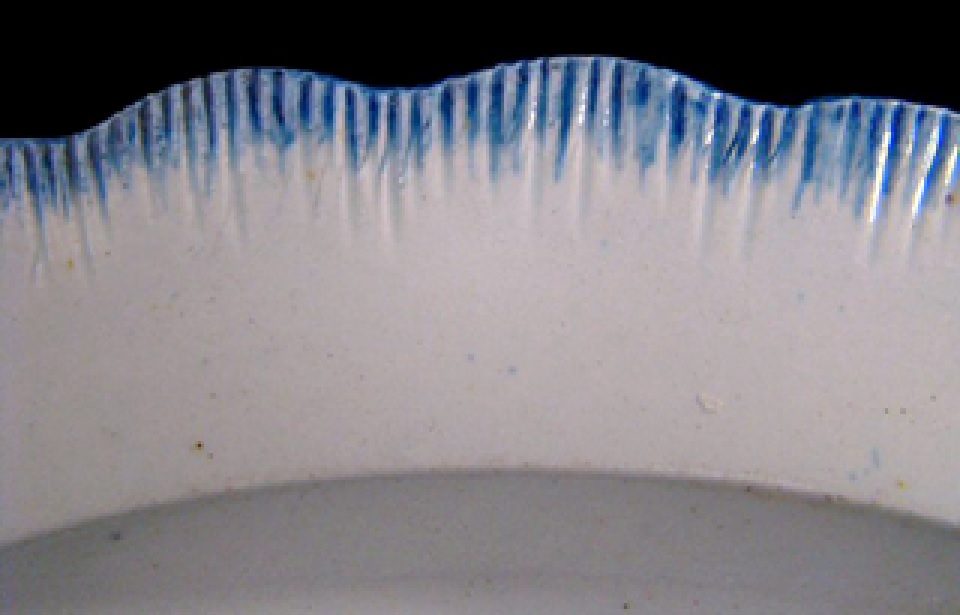

It’s the decoration that really makes this stuff special, though. It’s all hand-painted, and because the dried but unfired glaze is super absorbent, it has to be done with speed: the brush strokes are wide or thin, and it’s done in a fluid and moving motion, quick and rough, impressionistic, and almost living, and certainly not fixed like transfer-printed wares.

There is no way to erase the decoration once applied, which accounts for occasional errors, and which I think only adds to the attraction. The colour is almost universally a wonderful cobalt blue, but occasionally purple or orange is found. The subjects are largely naturalistic – foliage in particular – but there are also scenes with animals, people, and buildings. As well as actual pots, tin-glazed pottery was very much favoured for tiles among the wealthy, and some stunning examples exist.

I honestly love this stuff, there is something wonderful about it – the colours in particular – and although I don’t have a lot of it, it’s always a joy to find.

The next lot of pottery type occupies a similar space in time – broadly the 18th century – and indeed, overtook Tin-Glazed pottery in terms of popularity…

WHITE SALT-GLAZED STONEWARE (aka Fine White Stoneware)

DATE: c.1720-1770

DESCRIPTION: Thin walled, white glazed, impressed decoration, hard stoneware.

SHAPES: All sorts of tablewares (i.e. not cooking or storage), common are cups and bowls, but plates, platters, jugs, salt shakers, sugar bowls, etc.

A later development than Tin-Glazed, it was first made in the later 17th century, but only began to be produced commercially from the 1720’s onwards.

The fabric is a typical stoneware, in this instance with added calcined (burnt) flint to produce a pale cream, almost white colour. It is then fired at a very high temperature and salt glazed, to produce a fine, strong, pottery that I find really quite beautiful.

Vessels are formed one of two ways: either by being turned on a lathe when leather dry but before firing, which produces very sharp edges and fine horizontal banding; or by pressing thin sheets of clay into a mould, which allows the fine relief decoration to be made.

In this latter case, often the inside of the clay is wiped with a cloth to ensure the clay presses into every corner of the mould, which leaves very clear wiping marks, especially on closed vessels (jugs, for example) where the inside wouldn’t be seen.

External decoration, beginning c.1730, includes basket work patterns, leaves and other foliate designs, although simple incised horizontal lines are commonly encountered on earlier pieces.

Occasionally, the walls are pierced, though this seems largely confined to high-end expensive dinner services.

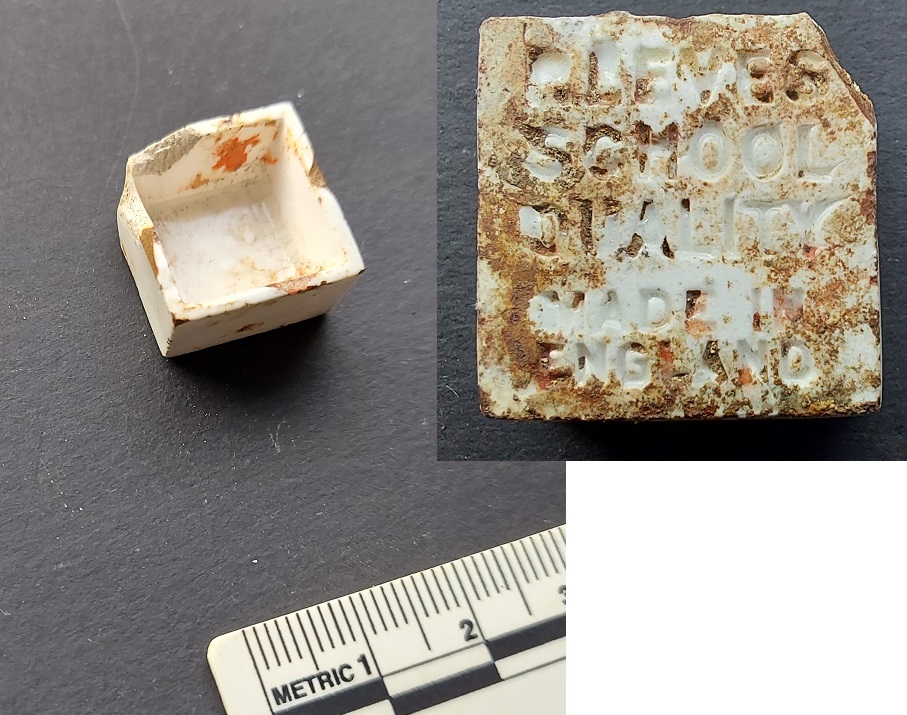

There are also rare examples of transfer-printing on stoneware:

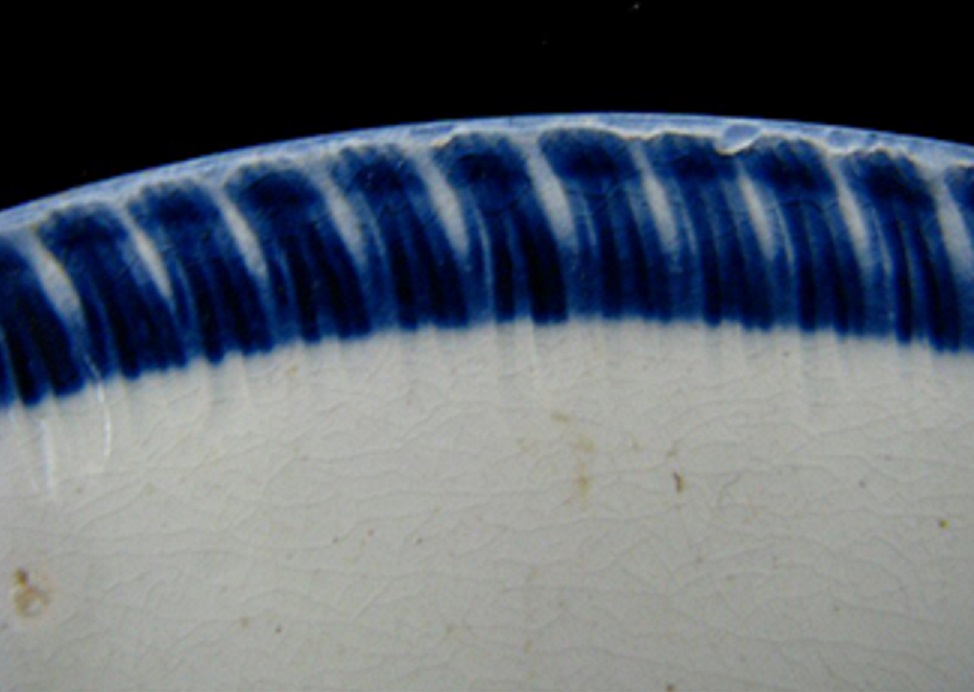

The exterior is salt-glazed, meaning that at a point during the firing process salt is added to the kiln, which vaporises and coats the vessels in a clear glaze. Although solid and even, it often leaves an orange-peel, slightly melted roughened type effect on the surface, as it does on the Brown Salt-Glazed Stonewares discussed here.

White Stoneware gradually overtook Tin-Glazed pottery in popularity, and began to dominate the fineware market from the 1740’s onwards – it is a lot lighter than the earthenware, and crucially it is much more hardwearing, with the surface unlikely to flake off or crack. It also appealed to the middle classes; its fine white background mimicking the desirable but very expensive imported Chinese porcelain, a crucial part of the tea and coffee drinking craze that had gripped Britain at this point. It remained popular until eventually overtaken by the development of Creamware and other earthenware types in the late 18th century.

SCRATCH BLUE

DATE: c.1740-1780

DESCRIPTION: Pale stoneware, incised decoration highlighted in messy cobalt blue

SHAPES: Mugs, Tankards, Jugs, Chamber Pots.

Broadly speaking, Scratch Blue is decorated Pale/Grey/White Salt-Glazed Stoneware – it has the same fabric and glaze. Essentially, this was a UK answer to the lovely looking Westerwald stoneware pottery being made in Germany (see below) and imported in large quantities – the English potters wanted a piece of the action, and produced a cut price version. It reproduces the essentials of Westerwald – incised decoration and stunning cobalt blue highlights on a pale stoneware (white-ish or pale creamy grey) background, but overall it tends to be more sloppy. The incised decoration is less careful, often looking as though it was done quickly, and the cobalt slip often overruns and splashes.

Actually, I think this ‘messiness’ was deliberate, a way of ‘jazzing up’ the decoration, and it’s certainly effective. That’s not to say that there aren’t some very careful and precise examples, though, and in fact American archaeology seems to divide Scratch Blue into two types – Scratch Blue, which is very finely decorated, and ‘Debased’ Scratch Blue, which is the messier variety. I’m not sure that the distinction is particularly useful, or indeed ‘real’ as such, but there you go – my twopenn’orth.

In terms of decoration, there are incised flowers and leaves and multiple horizontal turned bands at the top and bottom, all highlighted in cobalt blue and occasionally manganese brown. Also, there are applied medallions, sometimes containing the royal arms and cipher of King George II/III.

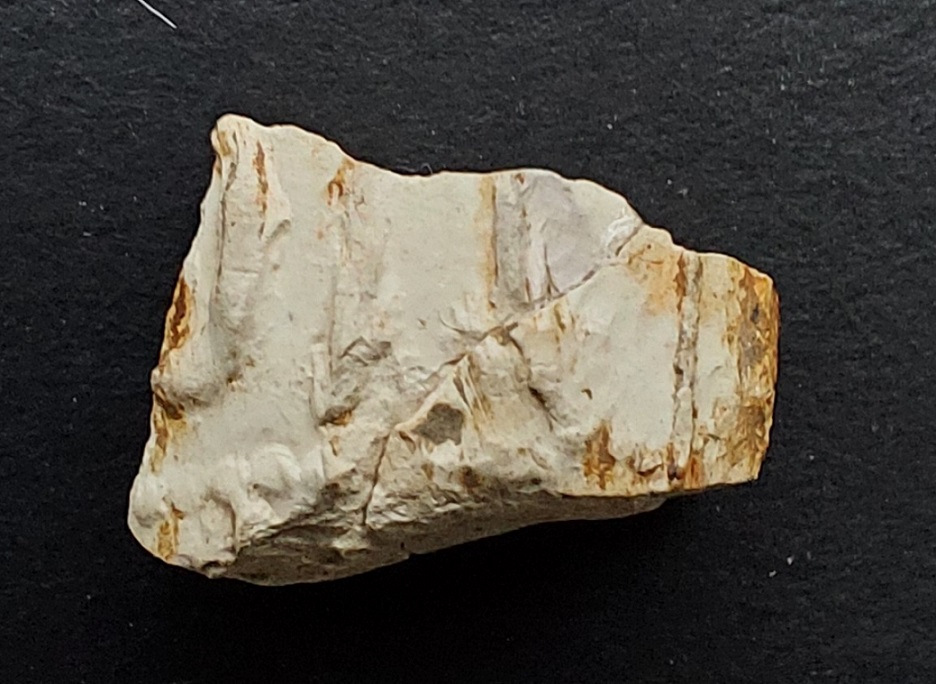

I have a single, very small, sherd of Scratch Blue pottery, and this stuff is by no means common, especially up North.

It seems to be from the base or top of a tankard, something like this:

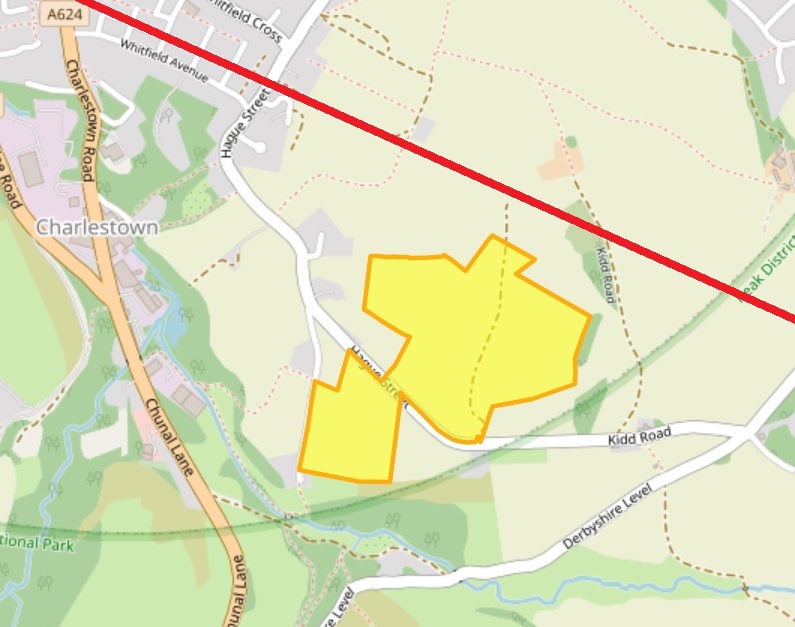

This seems appropriate as it was found on the footpath outside an 18th century one-time pub, the Seven Stars off Hague Street, Whitfield.

WESTERWALD (aka Rhenish Ware)

DATE: c.1650-1780

DESCRIPTION: Pale or grey Stoneware, incised decoration highlighted in cobalt blue

SHAPES: Mugs, Tankards, Jugs.

Unusually, I don’t actually have a sherd of this to show you! It wasn’t particularly common up in the North – London being the big importer and consumer of this ware type. As I said above, Scratch Blue is the indigenous British potter’s response to this German imported pottery, and as you can see it is very similar:

Incised decoration, cobalt blue highlights, applied medallions and other decoration, it is often difficult to tell apart. However, Westerwald seems to be bigger somehow, less delicate… and at the risk of offending our German cousins, more Teutonic. There also seems to be a greater use of cobalt decoration, and the background stoneware is darker in many circumstances.

And there the matter shall have to rest until I can find some Westerwald sherds to discuss at greater length (I might have to get a mudlarks license and head down to London and poke about on the Thames foreshore).

Right, I think that’s enough pottery for now – next time we’ll look at some fine earthernwares… you lucky folk.

Now, someone recently asked me if I could put links to all the previous Pottery Guides at the bottom of the post, so they can use it quickly to find out what they have… well here you are:

Part 1 – Marmalade Jars and Brown Stoneware (Nottingham and Derbyshire)

Part 2 – Spongeware

Part 3 – Industrial Slipwares

Part 4 – Creamware, Pearlware, and Whiteware

Part 5 – Blue and White Transfer-Printed, Flow Blue, and Shell-Edged

Part 6 – Porcelain, Bone China, Black Basalt Ware

Part 7 – 17th Century Slipwares, Manganese Glazed, and Yellow Ware

Enjoy, or not, as you wish.

Right, that’s all for now.

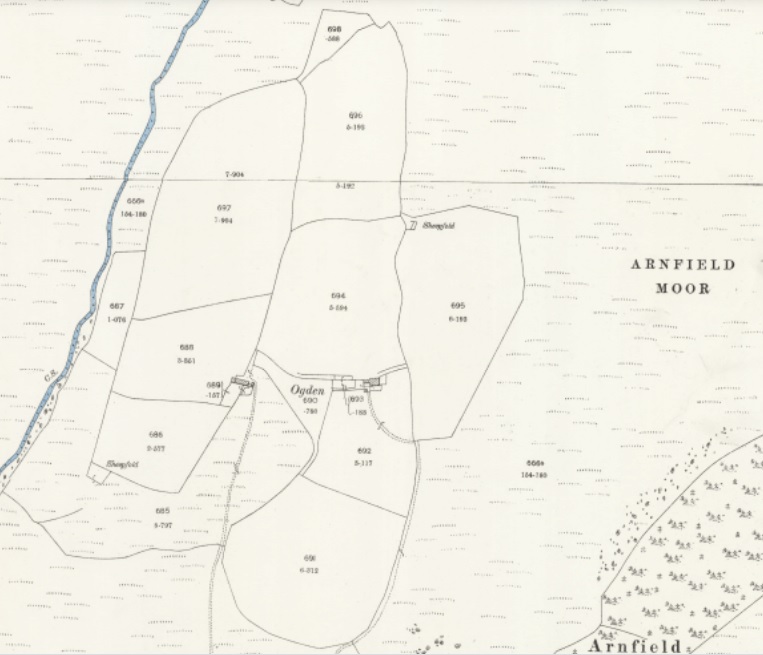

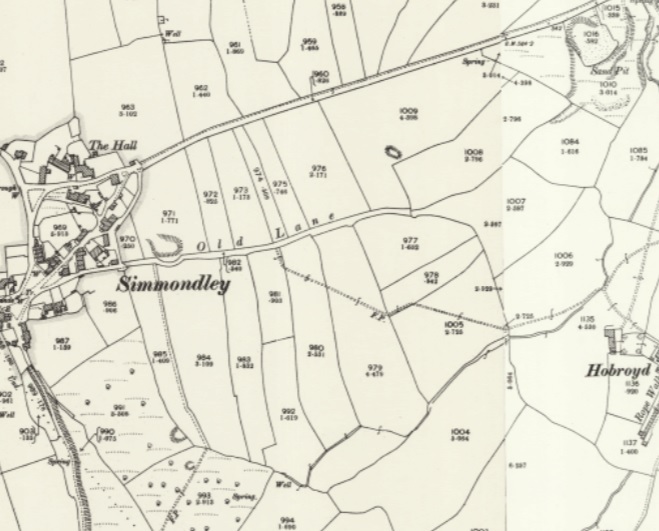

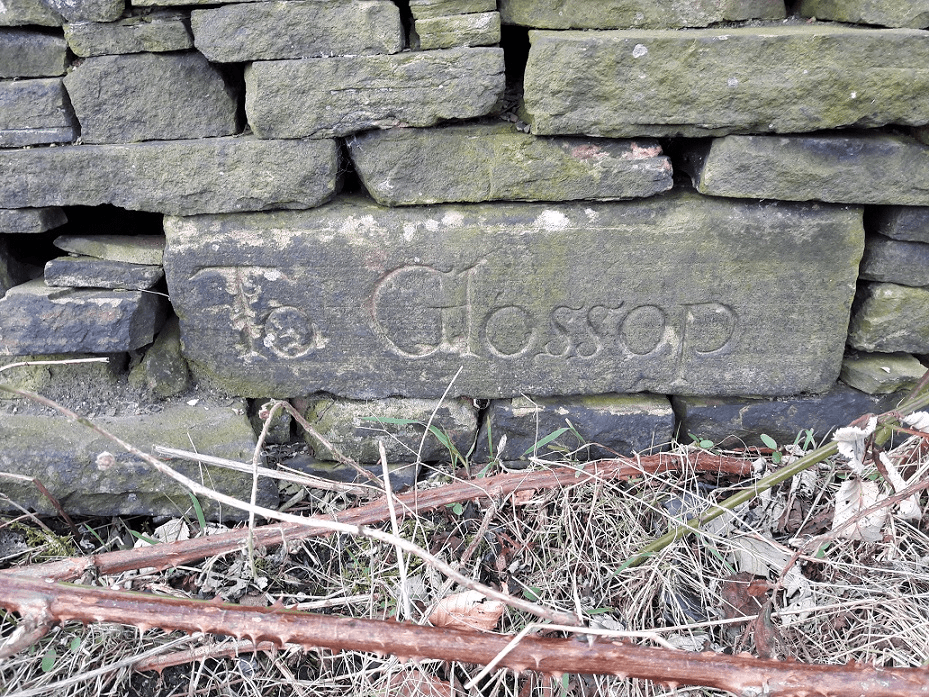

In other news, the Glossop Big Dig results are forthcoming… slowly. If any of you have any bags that need handing in, please do so, and I’ll get the results up asap.

Other other news is the ‘zine – Where/When – The Journal of Archaeological Wanderings – which is just about ready to go off to the printers. You will soon be able to buy a physical copy of a guided walk I did a while back, filled with historical musings and observations (and a sprinkling of pottery, obviously). It’s an experiment of sorts – we’ll see how it sells and whether I can make my costs back, but I’ve got about 6 more walks ready to go, and I’d like each one to be in the ‘zine. It will be full colour, 40 pages, fully illustrated, and should be retailing for £6, but watch this space.

If any of you out there have either suggestions for walks, or would like to publish one yourself, do get in contact. More news on this soon.

Until then, look after yourselves and each other, and I remain.

Your humble servant,

TCG