What ho! Fancy meeting you all here…

Happy summer everyone! I hope the season finds you in good form… or at least not in actively terrible form. Having recently celebrated a somewhat significant birthday with a trip to Naples area – Pompeii and Herculaneum included – I returned exhausted, and filled to the gunwales with pizza, wonderful wine, and archaeology, which pretty much sums up my life, to be fair. I can heartily recommend such a trip, although it was a tad expensive, and I can now only just about afford to camp in my own garden!

Whilst I was there, I actually wrote a blog post about a Wander to the beach I made, and that I thought you might enjoy; this was meant to be it. But I haven’t finished it yet, obviously, and so we have to remain close to home today. I mean, it’s not quite as glamorous as Pompeii or the Bay of Naples, but Whitfield is just as interesting. Kind of.

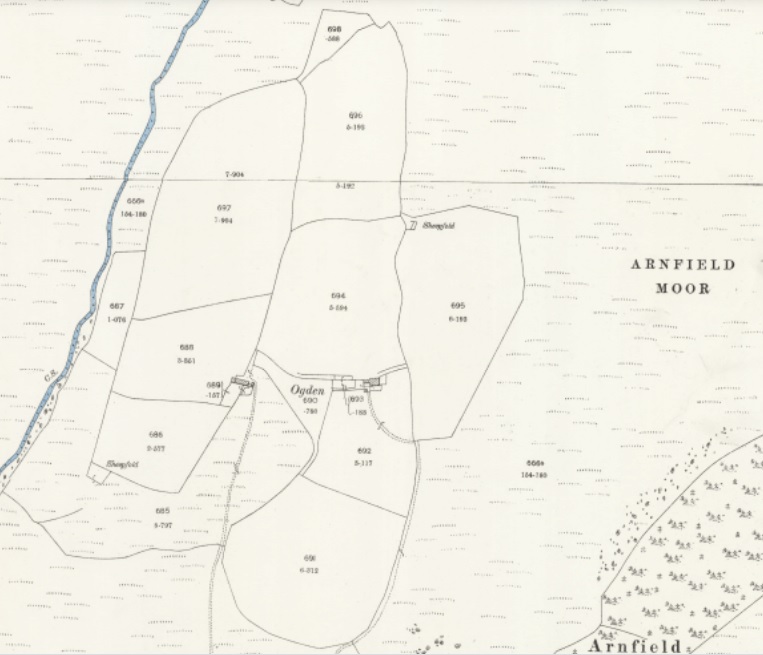

Anyway, I’ve often wondered about this place – Whitfield Green – a farm that is marked on older maps, but which is clearly no longer there.

I mean, the building is clearly old, and is clearly marked Whitfield Green, but I can find absolutely no information out about the place. So I went exploring…

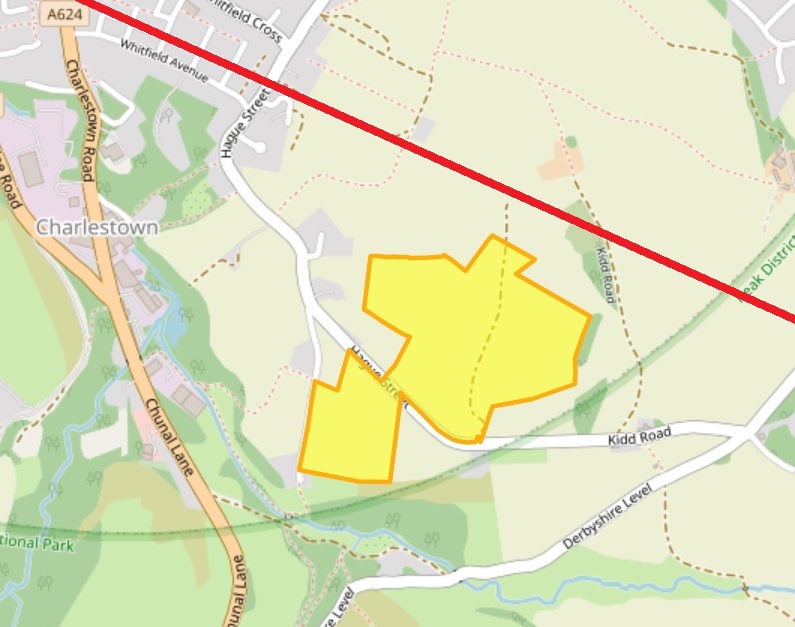

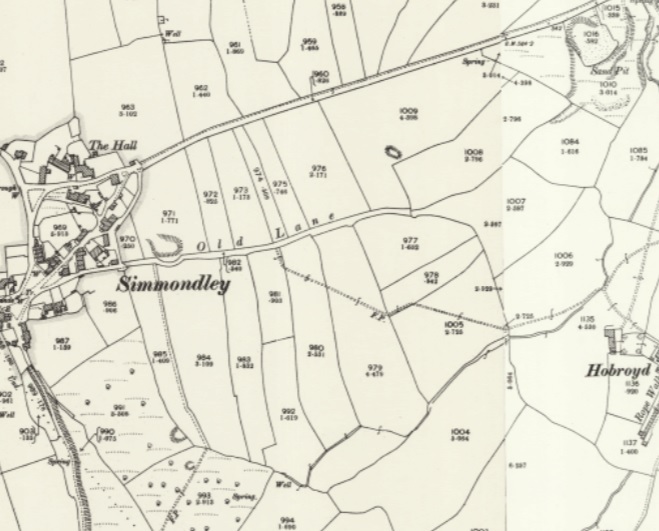

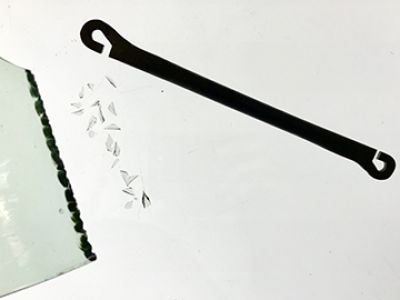

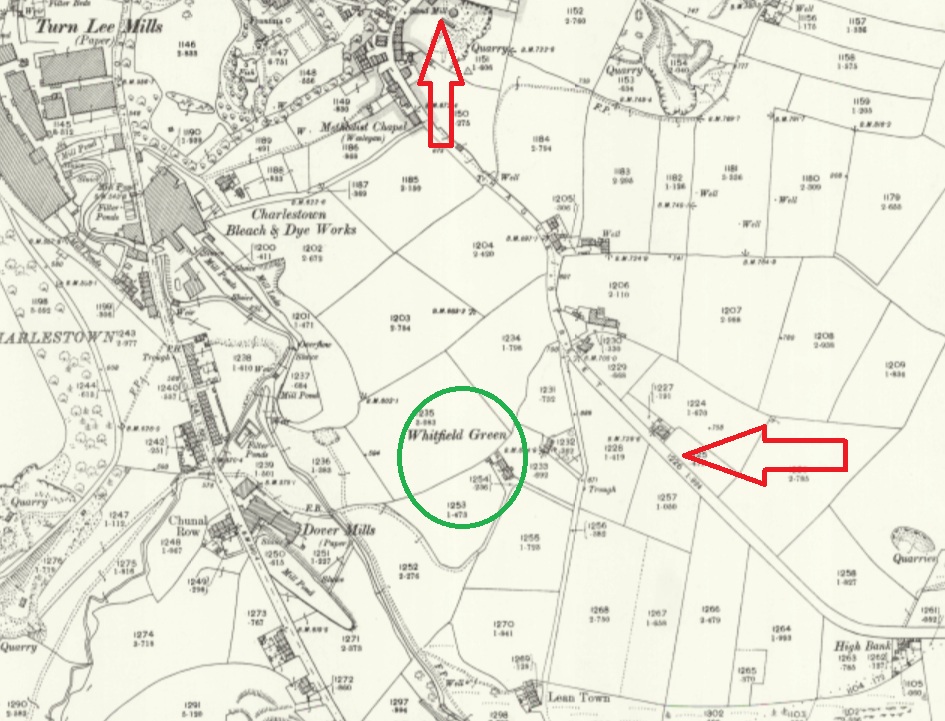

Firstly, the roads. The whole area around Derbyshire Level and Lean Town has been monkeyed with following the Whitfield Enclosure of 1813, so it is sometimes difficult to see exactly what went where before that point. Map work and physical walking helps, and it seems the road originally went along the lines of the red line in the map below – it continuing straight at Lane Ends Farm, instead of kinking left as it does now, and continues to Whitfield Green, thus:

You can see a hollow where the field edge is now, and it is visible on LIDAR.

From here (with numerous branches, and marked in red below), this track would go under Lean Town, and then onto Gnat Hole, and then to Chunal – unbelievably, it was once the main route from Glossop and Whitfield to the south – Buxton, Chapel en le Frith, etc.! However, when the Enclosures happened, one of the stipulations in the act of parliament was the building of wide solid roads – hence we have Derbyshire Level, which, whilst incorporating numerous existing routes, was a totally new road – no wonder when you look at state of the roads at that point. In fact, so bad were the roads that Glossop historian Ralph Bernard Robinson, writing in 1863, noted that

“Glossop, till a comparatively recent period, was a place difficult of approach, and, in some circumstances almost impassable, owing to the nature of the roads. They seem to have no roads but such as the Romans, ages before, had made for them.”

So it is at this point, with the radical shake up of the roads that followed the Enclosure Act, that many of the trackways with which I am obsessed become obsolete, and so it is with the red trackway, the access track to Whitfield Green – it simple ceases to be needed as the new road that goes down to Lean Town was made, and a new access track came off it. This is the footpath you now walk down in order to get to where Whitfield Green once stood (marked in green in the map above). Kidd Road was once known as Whitfield Green Road, and actually, I suspect that it once went across the field and that this ‘new’ access path is in fact the old route preserved, once the whole area had been monkeyed with (marked in blue, above).

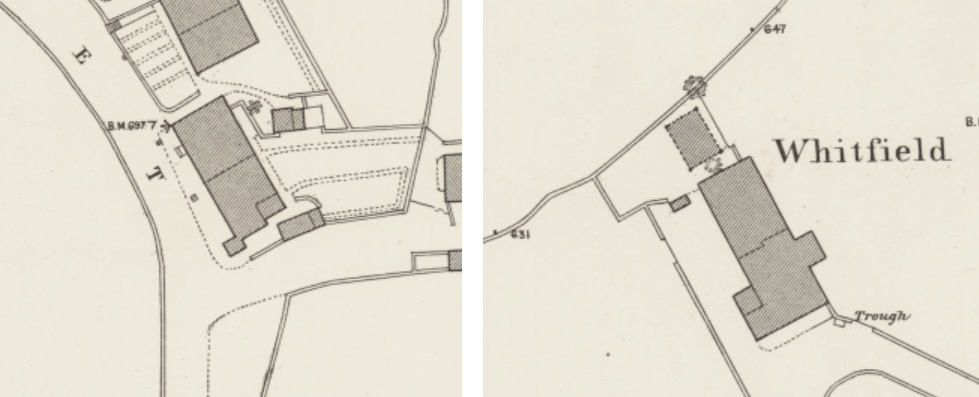

Indeed, Derbyshire Level, and the spur around Moorfield, combined with the Turnpike Road (Charlestown Road) meant that there were now new solid roads along which to travel, and thus the old muddy route below Lean Town and through Gnat Hole was no longer used, and the whole became footpaths. It also meant that new farms could be built, and it is at this point that I think Whitfield Green Farm was built, just to the north of Whitfield Green (circled in yellow above). It is still there, but is very difficult to see without being arrested for “acting suspiciously near an innocent person’s house”… again. It has a stone roof (so making pre-1850ish), but there is nothing that points to it being older that the first half of the 19th century, and I suspect that once the new Lean Town road was made in 1820, someone took the opportunity to build a new farm there.

We know Whitfield Green was there in the 1920’s, but no longer appears on maps from the 1960’s onwards, so presumably it was demolished between those dates. A pity, but there you go, such is the nature of progress. Thus, the timeline seems to be:

1720 (ish – maybe before, maybe after) – Whitfield Green built on existing track (in red), and also accessed via another track (Kidd Road, in blue)

1806 – Lean Town built on the same (red) trackway

1810-13 – Whitfield Enclosure Act, and thus…

1820 – New roads made, including Lean Town road, and access to Whitfield Green comes from that now (albeit via an existing track).

1825 (ish) – Whitfield Green Farm (the new one) built (in yellow)

1950 (ish) – Whitfield Green demolished

That seems to tally with what we know, but if you think differently, let me know – click the ‘contact’ button at the top, or leave a comment… I’m always happy to hear from you.

So what did I find when I went to look at where Whitfield Green once stood, I hear you ask. Well, I’m glad you asked, because I found:

However, look closer and…

It was the flagged floor that really brought it home that this was actually once a house; I love that moment when archaeology meets actual lived life; spooky, yet intimate, an odd feeling. It would be great to have a proper scrape around and uncover more of whatever remains.

And pray what, if anything, did you find there, you strange, pottery obsessed, person, you? Well, I’m glad you asked that, too:

So far, so Victorian. However, against this background there were several sherds of older pottery lying around:

Then there is this lovely thing, and I am aware that ‘lovely’ is an entirely subjective concept.

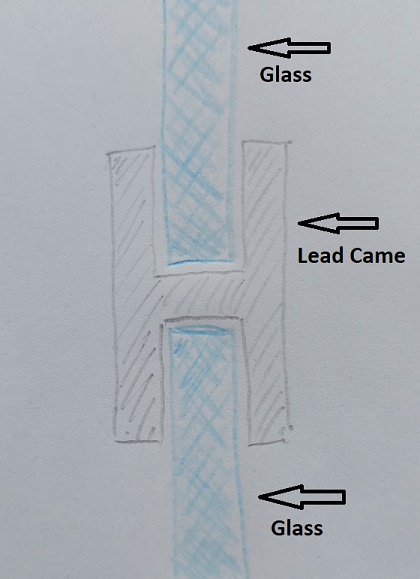

It’s the wide strap handle to a large cooking pot – this sort of thing:

The fabric is unusual, though – very hard, with a purple colour, and a black and white mixture of inclusions – it’s a sort of Midland Purpleware, almost Cistercian Ware, and not at all like the normal Black Glazed stuff that you associate with Pancheons. Lovely stuff.

Also, there is the brown stoneware. Some Victorian Derbyshire Stoneware, but also early 18th century Nottingham Stoneware:

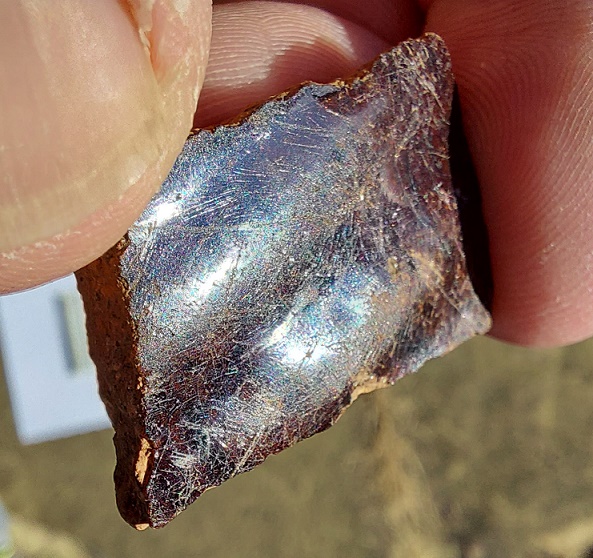

And finally, I found this:

Shiny (though sadly scratched), it still has the silver looking surface – which it was designed to do – and is a lovely thing to hold… that personal touch, again (you can see a better preserved example here). The back shows signs of it breaking down (the green bloom of copper), but also the reddish iron rust of where the loop that once held it in place was. This button is nothing special as such, it is plain, and of relatively poor quality, but it is dateable as Tombac plain buttons such as these were used from mid-18th century onwards (stopping perhaps late 19th). I love this thing… so intimate. Did it belong to someone who lived on the farm? Perhaps.

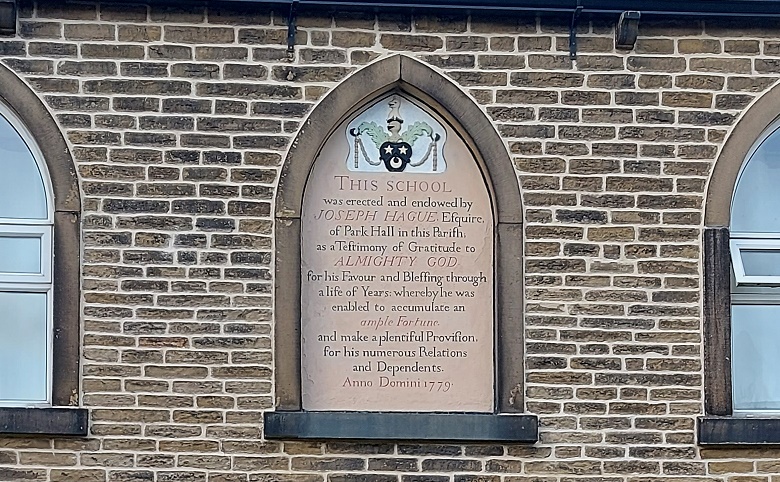

So there we have it… the farm. As to what it looked like – well I have found no photographs, but I would suggest it looks like this farmhouse on Hague Street; it’s about the right age, and has a similar layout/shape – although Whitfield Green is larger – and is also divided into two dwellings. Interestingly, they both face south-west. I hadn’t noticed before putting them on the page, but it makes sense as it maximises sunlight, and thus light in general.

There is no information in any of the usual books, and there are only a few references to it online. According to the ever wonderful and always useful GJH website, a Robert Wood, born in 1713, is described as being of Whitfield Green, as indeed is his son. So we know that by 1740 or so? the farm is there, and it suggests that the name of the farm is simply Whitfield Green, and that the later building took the name Whitfield Green Farm to distinguish it. There are later references, but this seems to be the earliest, and thus we have the name of someone who may have walked on those flags, and who may even have worn the button.

Well, that’s your lot for this month. I’ll try and get round to posting another one if I can – more pottery, obviously (ignoring the groans).

**EDIT**

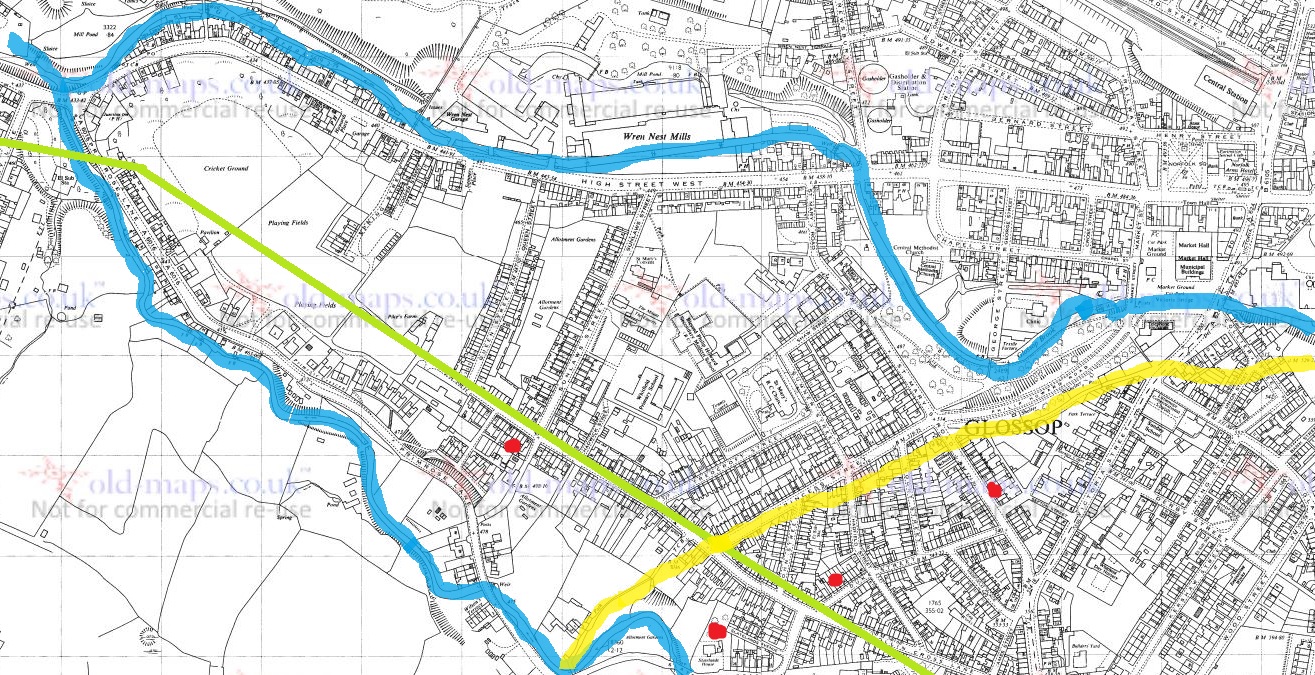

I went back to the site today, blackberry picking with Family TCG, and I found this lovely little sherd of Manganese Mottled Ware:

Its from a cup or tankard, and dates to the last part of the 17th century or early 18th, so within the range of our building. Or perhaps we should revise the date back a bit? Certainly the late 17th century saw a lot of building work in the Glossop area, as a glance at the Datestone post will show you. Again, a little excavation (or a photograph!) would show us a bit more.

In other news, the new Where/When will be out soon – more info when it happens, but this one is a truly awesome Wander around Mellor – just over yonder! It has medieval field systems and farms, Victorian noise, Iron Age hill fort, medieval crosses, cracking views, a terrifying viaduct, bench marks, a trig point, wonderful gateposts, and it starts and finishes at a pub… what’s not to love? Here’s the cover to tempt you.

Righty ho, I’m off. I have housework to do before I’m allowed a glass of the stuff that cheers – Mrs CG’s rules, which I can’t help feel is unfair… into every life a drop of rain must fall, and all that.

More soon, I promise, but until then, look after yourselves and each other. I remain,

Your humble servant,

TCG