What ho, you wonderful people you, what ho!

Well, I have an interesting offering for you this time, and one that doesn’t involve pottery, sadly. I know, I know! I can hear your yells of pain and misery from here… and my how they sound like whoops of joy and celebration. Joy and pain are two sides of the same coin I suppose – the Yin to the whatsit, and all that. Although, I have to say the chap who appears to be doing a buck and wing clog dance whilst singing ‘Happy Days Are Here Again‘ does seem to be hiding his sadness a little too well… Hmmmm.

Anyway, I digress…

So, I have a friend who bakes cakes, she’s something of a connoisseur as it happens, and people are always giving her cakes as presents. Practically throwing them at her. I have another friend who takes his music very seriously, and people are always giving him records and cds with the words “I thought you might like this“. I have yet another friend who likes his beer, and scarcely a week goes by without someone bunging cans and bottles his way, saying things like “I was in Harvey Leonards the other day and I saw this and thought of you” – almost drenched in the stuff he is… and permanently inebriated.

So, I like old things… and especially pottery.

Now, I was once at a dinner party, glass of the old stuff that cheers in hand, swaying slightly, and conversing with a chum, when another chum bounded over and said “What ho, TCG! Oooooh, I say old bean, I have a gift for you” and off he scurried. He returned moments later clutching a plastic bag which he handed over to me. What could it be? It was like Christmas! Excitedly, I opened the bag…

What it was was a half a muddy brick. A perfectly normal 19th century house brick, broken in half, and still damp. They thought it might be old and presumed I’d want it.

Well, I mean to say, of course one doesn’t look a gift thing in the old whatsit, but… well… You know. And this sort of thing happens surprisingly – worryingly – often. So you can appreciate then why the words “I’ve got something for you” can sometimes sound a note of concern.

Don’t get me wrong, I very much appreciate the thought, it’s kind and most welcome. Honestly, little packages clinking with pottery fill me with a warm fuzzy feeling, and truthfully I’m never happier than when I’m rifling through shopping bags of finds, furtively handed to me in the park, looking shiftily around, like some sort of Soviet-era spy game. Indeed, being able to answer people’s questions of ‘what is it?‘, ‘how old is it?’, and the often asked ‘what’s wrong with you?‘ is the reason I write this website… and why all seven of you read it.

But for the record I also like beer and music. And money… a shiny shilling or two wouldn’t go amiss, either. And did I mention the stuff that cheers? I like that a lot!

Other times, however, gifts clasped tightly in hands can be amazing. I have had some genuinely wonderful, alarmingly, breathtakingly beautiful, and truly interesting things given to me to look at: pottery, bricks, flint… spoons!

And so it was the other day that I was skilfully tracked down by the always wonderful S.T. who thrust at me a cardboard box, tattered at the edges, and yet so full of promise (the box that is, not S.T… good old S.T. looked radiant as ever).

And that is the start of this episode. The objects contained within – on loan in a distinctly non-permanent way – were all found in the fill of an old mill pond, the exact whereabout of which are shrouded in mystery (but which I’ll happily disclose for the price of a glass of something nice… I never said I had scruples, nor that I wasn’t cheaply bought).

So come, let’s explore the box together.

The box itself is interesting – an armorial device with the initials DSC and a motif of crossed razors… a quick Google search tells me the Dollar Shave Club. Now, given that I have water from the holy well at Walsingham Priory safely contained in a medical urine sample pot, it’s not my place to pass comment. The box is, however, different from their normal home, which is apparently an old clock. Mind you, this is the same S.T. who uses an egg as a scale in her photographs… so nothing should surprise us.

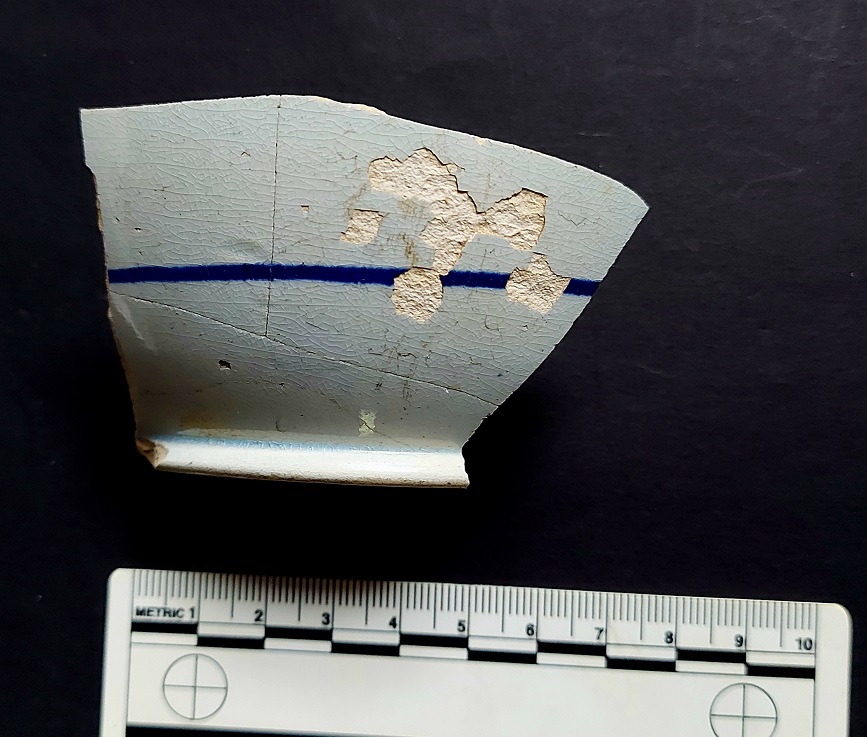

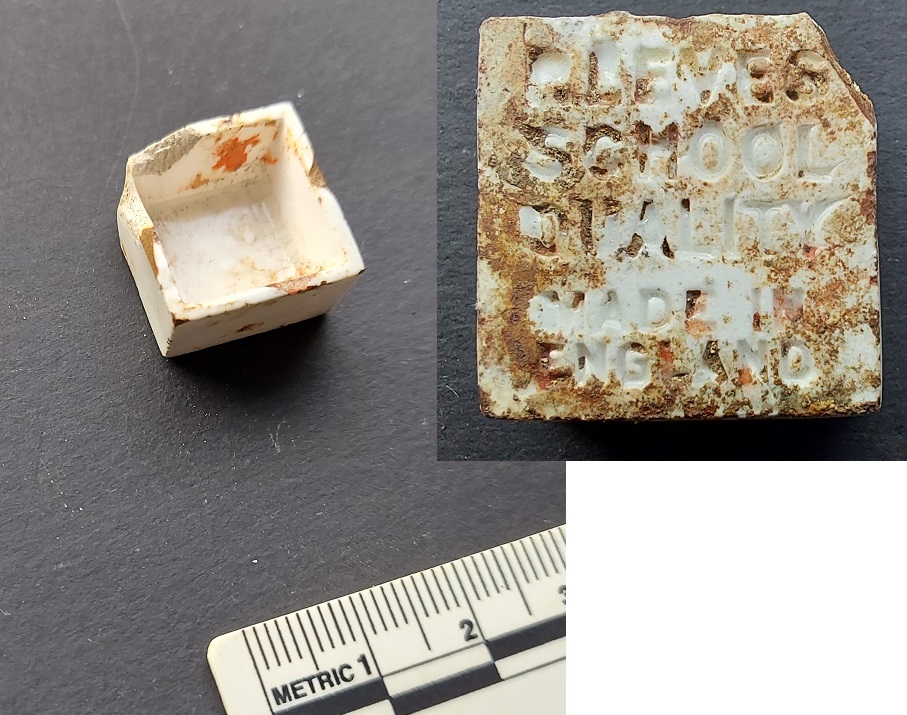

So what was in the box o’ bits? First up, a clay pipe stem.

Plain apart from the words “UNION” and “PIPE” stamped on the sides. I browsed my sources for information about this, but came up with nothing, alas. It is probably an example of a political pipe, that is those that carried slogans and allusions to important political ideas and events of the day. No doubt this one was connected with the idea the Northern Irish union with the United Kingdom. The Unionists demanded to remain part of the UK in the face of an increasingly independent Republic of Ireland, which itself was demanding that Ulster be a part of it. It’s an interesting history, and one that obviously resonates still to this day. Given that a lot of clay pipes were aimed at a target market of Irish immigrant workers in Britain, it’s unsurprising that many of them contained words and phrases that reflected politics back home. Indeed, such was the market that many clay pipe manufacturers even gave their address as Dublin on the pipe bowl, despite being made in Birmingham or similar. It also plays on the belief held at the time that somehow Irish clay pipes were superior in quality.

The mouth piece is interesting, and shows the manufacturing process clearly. Formed in a two-part mould, the pipe often has mould lines along it length that can be quite thick and sharp, especially if the mould is old and worn and doesn’t close properly. The answer is to pare away the flashing with a knife, which you can see happened here.

Date wise, the shape (straight, and quite chunky) would put it sometime in the early 20th century – let’s say 1910? It looks similar to the shape of the McLardy pipe here, and it would also fit with the political message.

Next up… a boot!

The detail of this thing is amazing; it’s old – probably Victorian in style – and one of those boots with an elasticated side (I actually have a pair, and very dapper I look in them too). It’s made from pewter or similar – lead-based, certainly. I have no idea what it actually is, but it’s possibly some sort of charm – if you look closely at the front you can see the remains of a small ring which would have been used to hang it from something… a pocket watch perhaps. Or, it might have been a pin cushion, with a material filling the hollow allowing pins to be pushed in.

However, whilst looking closely at it, I noticed something.

You can just make out a pair of tiny mice, one on each side, crawling up the boot.

A mouse in a boot or shoe was a common theme in the Victorian period apparently, and the Northampton Museums website seems to provide an answer why:

“Shoes can be thrown at weddings to wish the couple a good, long and useful life. The shoe was also a sign of fertility and many years ago a boot was often buried in the home of the newly wed couple. Inside the boot was placed a grain of corn, which it hoped would attract mice to nest and breed. From this came the idea that the wife would bear lots of children, who would look after her and her husband. Many Victorian miniature shoes show a mouse playing in the shoe.“

So there we go – vermin in your footwear can lead to many children. Who knew?

Next we have some toys, and to start with, a wonderful hollow cast tin soldier.

Remarkably, he still has his head, which is normally missing from found soldiers. The paint is in good condition, to0 – blue trousers and a red tunic. To make these Victorian to early 20th century figures, a mould is made into which a molten tin alloy is poured. This cools immediately on contact with the exterior, and which allows the still molten interior to be poured out, thus saving on tin. They were hand painted, probably using some very nasty heavy metal based paint – so don’t chew any you happen to find.

When new, he would have originally looked something like this:

This example is certainly better than the one I found… very jealous!

Next up we have… well, let’s not beat around the bush. We have nightmare fuel. The kind of thing that haunts my dreams.

I’m not fond of dolls, they honestly give me the creeps. But I think it is quite common for humans to be unnerved by things that look quite like us, but which aren’t us; the ‘Uncanny Valley‘ is the term for such feelings. It’s not an outright phobia, more a dislike or a sense of unease. Although I have to say, I do like the expression it has – a sort of open-mouthed surprised look… not unlike my own expression when I unwrapped this wonderful, if creepy, item. So then, here we have an remarkably complete Victorian bisque – or unglazed porcelain – doll. It’s tiny, and only the body remains – the arms and legs would have been a material, or perhaps porcelain with a single rivet joining them so that they were movable. The whole would have been clothed, or wrapped in a blanket, but this has long since rotted. The incredible detail in the colouring of the eyes, hair, and face would indicate that it was a relatively expensive one, and it would have looked something like this when ‘alive’.

On the back is impressed the word ‘Germany’, which is where the doll was made, Germany being world renowned as the centre of doll manufacturing. There is also the number ’61’ just visible on the left shoulder, which is presumably the mould number.

Sadly I can’t find any more information about this doll in particular, but at one point this was a prized toy belonging to a little girl, and at some stage the doll was lost or thrown away. A melancholy thought.

Next up is… yep, more nightmares made solid! Thanks for this, ST.

Another bisque doll, and whilst it is complete, it’s just the head and shoulders, which would have been sown into a cloth body. It would have been sold very cheaply as there is no painted features, but would nonetheless have been a much loved toy. You can see how it was made – cast in a mould, and hollow:

Creepy, but a wonderful

Whenever I find toys or marbles, I always feel slightly sad that they were lost or discarded. I don’t like the idea that somehow the things that matter to us as children shouldn’t matter to us as adults, and that there should be a clear and clean break with our childhood. Luckily though, I’m the adult now, and I get to decide what being ‘an adult‘ means… hence I have display cabinets filled with Star Wars and Action Force toys – and Airfix toy soldiers – from the 1980’s in our spare room. My childish things are very much still with me… but I digress. Again

After those last two I need a snifter of something that cheers.

Well, we started with a pipe, so let’s end with a pipe. Truly, I would love to smoke one. There is something wonderful about a pipe, something calming; the chap who takes charge in a crisis smokes a pipe. As does the dashing hero, or the bookish academic, or the romantic lead. Sadly, it’s that damned cancer that puts me off (that, and Mrs CG threatening divorce).

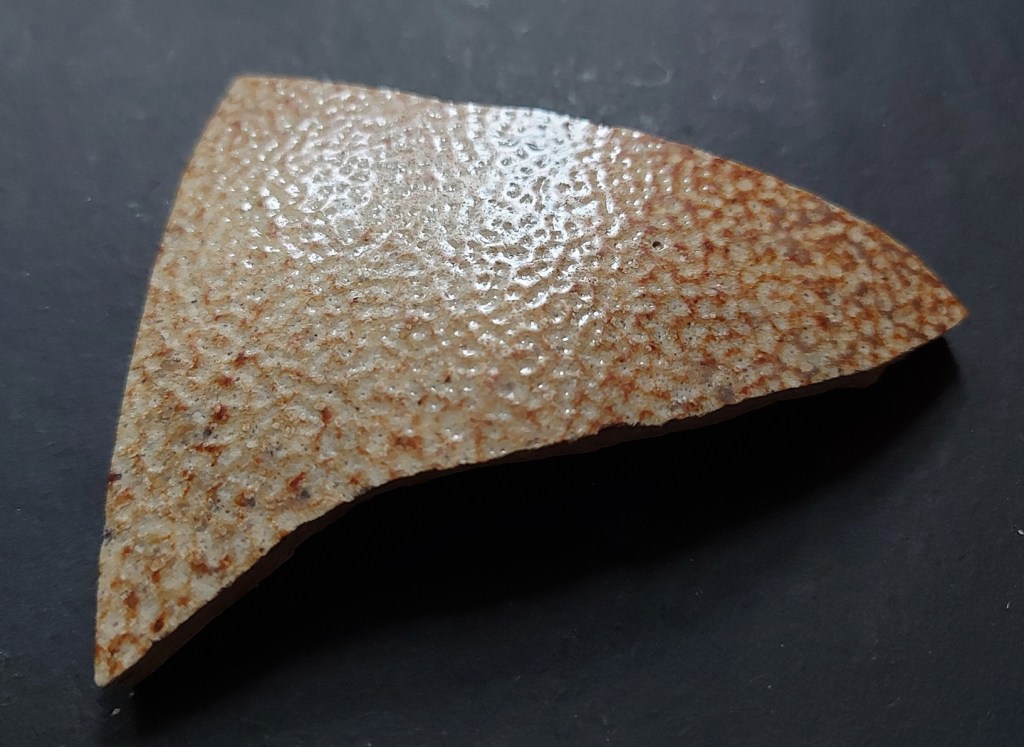

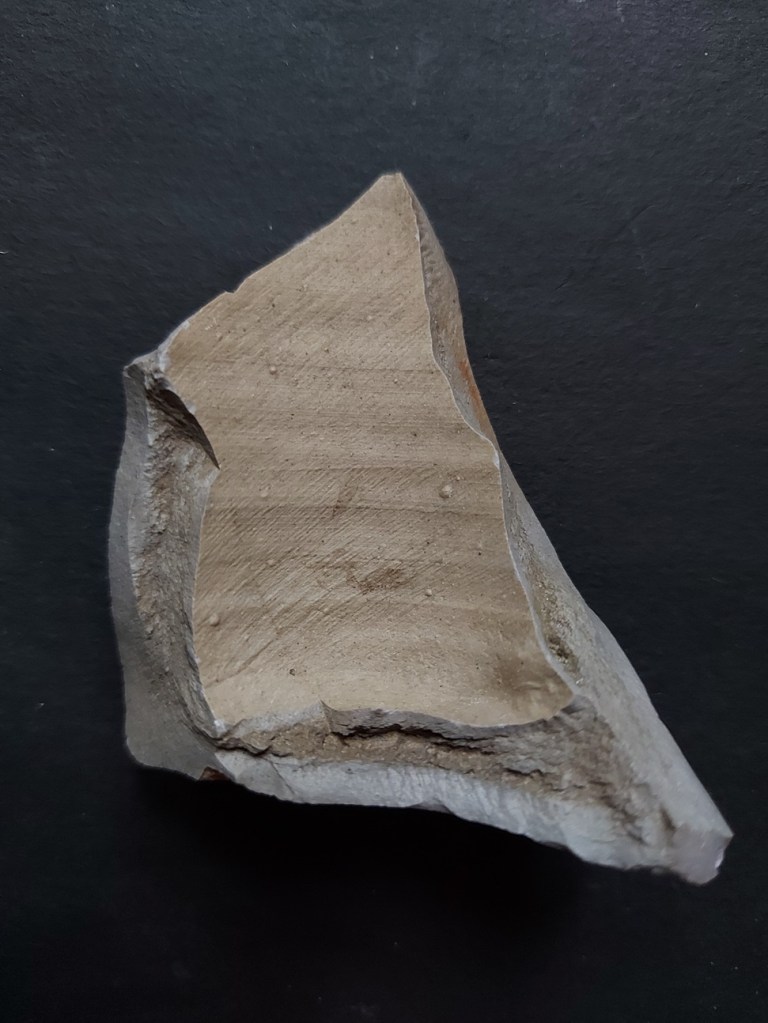

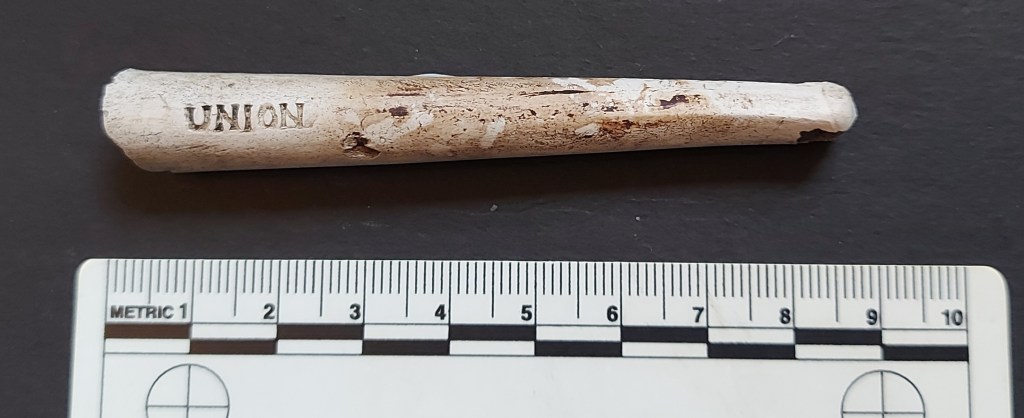

So here we have here a fairly standard, but always welcome, Late Victorian clay pipe.

I actually have a whole article on clay pipes almost written, so I won’t go into too much detail here, but it’s the shape and size that tells us the date (briefly, if it has a bulbous bowl and slanted rim, it’s Georgian or earlier. But if it has an upright bowl and horizontal rim, then it’s Victorian. Also, a smaller bowl is earlier, whilst a larger bowl indicates it is later.

There is some lovely, if very common decoration on this pipe:

The rouletting around the rim is very typical of the type, as is the stitching on the front and back, which hides the flashing caused by the joining of the two sides of the mould. There is no maker’s mark, not even a ‘Made in Dublin’, or similar Irish theme, alas. And as I say, certainly not uncommon, but always great to find one in good condition.

And with that final pipe extinguished, the journey is over: the ‘box o’ bits’ has been explored, and we may all go back to whatever it was we were doing before I interrupted. My sincere thanks to ST for allowing me to share this with all seven of you, and for following and supporting me for so long here at the Cabinet of Curiosities.

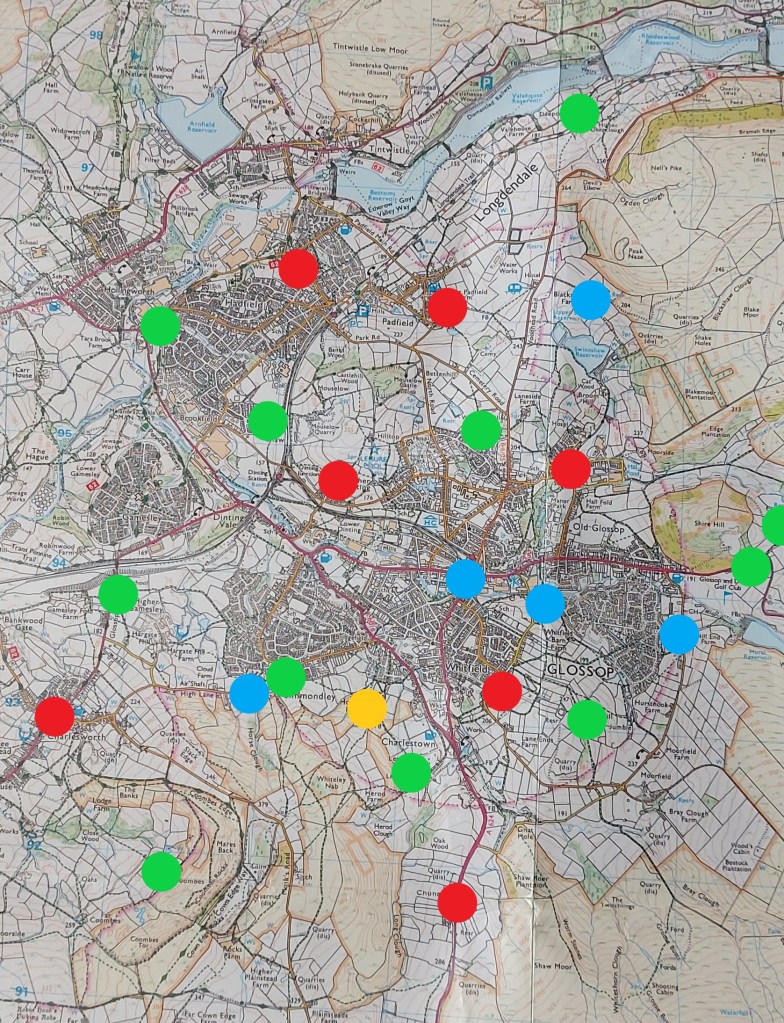

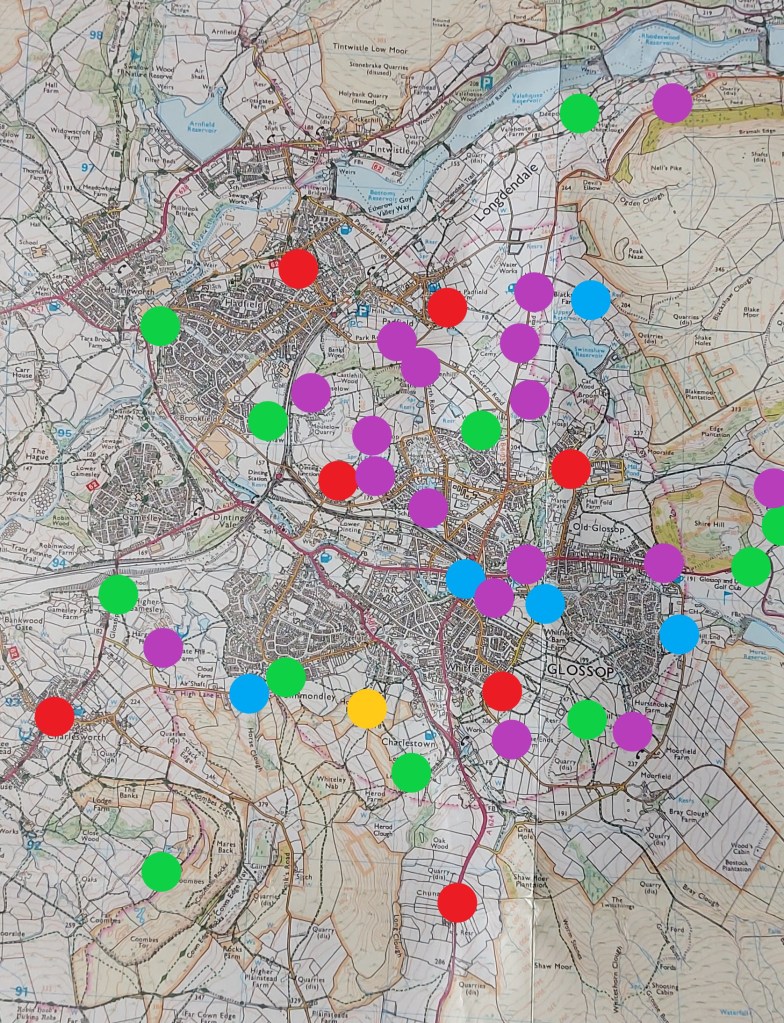

In other news, I’m currently putting together the next edition of Where/When – this one covers a walk from the Bull’s Head in Old Glossop to The Beehive in Whitfield along ancient trackways, and taking in some interesting archaeology. As usual, you will be able to buy a physical copy, as well as download a digital version. I’m also going to do it as a guided walk, so you’ll get a chance to Wander the route with me – which may or may not be a bonus, depending on how much you like pottery! Watch this space.

Talking of which, more pottery next time. But until then, look after yourselves and each other.

And I remain, your humble servant.

TCG