Well that got your attention! What ho, wonderful people! What ho!

Up by Coombes Edge lies Cown Edge quarry. This quarry, long disused, contains a number of interesting, and oddly well executed, carvings on the walls. I have heard about this particular place – and its carvings – many times, and from many different people, but had never managed to get up there. No reason, simply that there are so many places to see, and so little RH. A few months ago, a friend (my thanks to Andy T) suggested a walk up that way and, well, I thought, let’s have a look.

What I like about this place is not just the ‘historical’ history, which is visible and tangible, but the ‘personal’ history which is similarly visible, but often better felt than seen. The quarry seems to be one of ‘those places‘; a destination, a space in the landscape that attracts; a shelter, an asylum, a place of freedom, and perhaps decadence. In particular, it’s place where ‘youths‘ go and be ‘youthful‘, frolicking, feeling, fumbling, and… well, you get the picture. I didn’t grow up in Glossop – I’m a ‘comer-inner‘, so to speak – but if I could take you to Cheadle Hulme where I did grow up, I could show you a few such places from my youth. Every town & village has them – and the similar stories they could tell of the first time drunk, illicit substances consumed, virginities lost, love discovered, best friendships forged, fights fought, and the always difficult transition from child to adult negotiated – often on the same evening. But perhaps most importantly, memories are made. To quote Wordsworth “Bliss it was in that dawn to be alive, but to be young was very heaven“. I have recently turned 47 (young for some of you, old for others… it’s all relative), and have been marvelling at the swift passage of time, so forgive the nostalgia. Now on with the show.

Cown Edge Quarry seems to have been started sometime in the early 19th Century, probably as a source of roofing stone. Geologically, the stone is Rough Rock – a type of sandstone of the Peak District and southern Pennines, and the most commonly occurring of the Millstone Grit group.

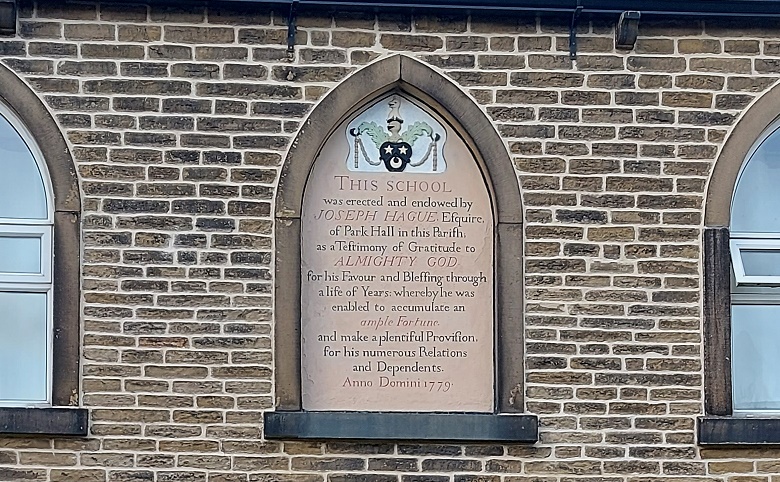

Incidentally, and as a rule of thumb, you can roughly date the buildings of Glossop by what the roof is made from. Prior to c.1850 roofs were made from stone taken from local quarries such as these. However, once the railway arrived (c.1850) Welsh slate could be imported on trains. Not only was slate cheaper, but it also weighed less so the roof could be constructed using less timber, and so roofs after 1850 tend to be made of this. A rule of thumb not an absolute guide, but useful nonetheless.

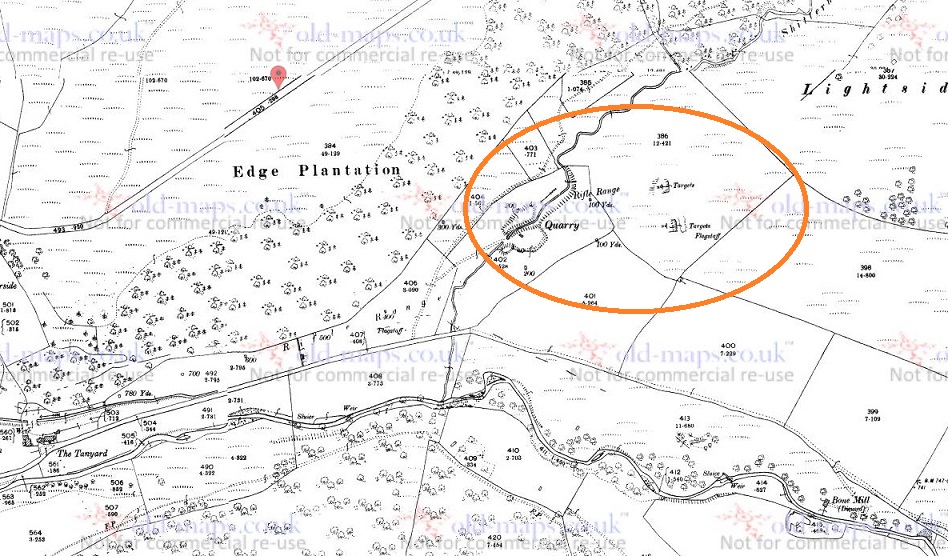

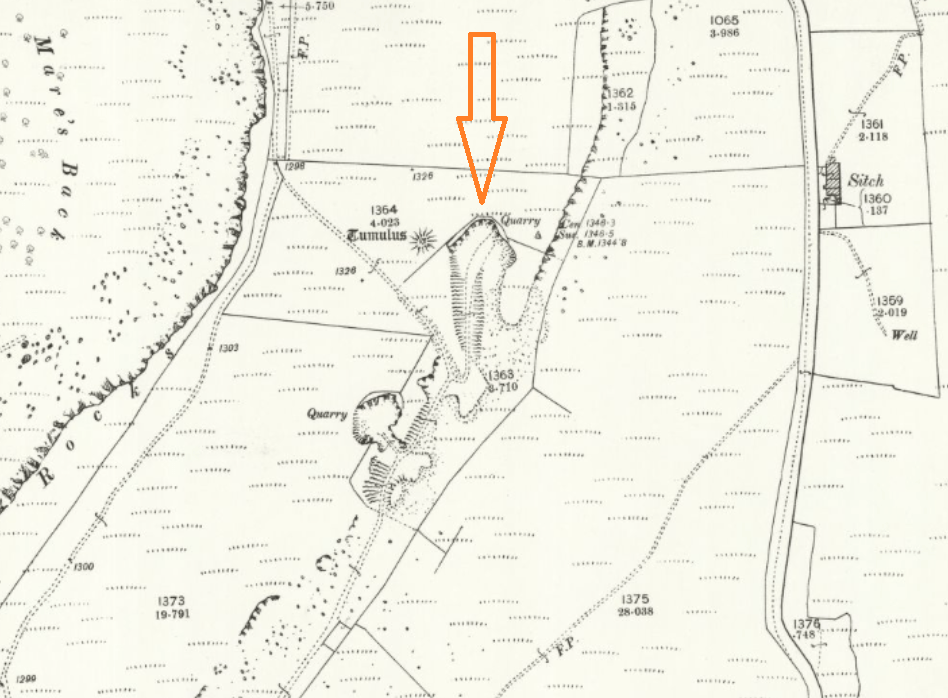

Anyway, the quarry is located here:

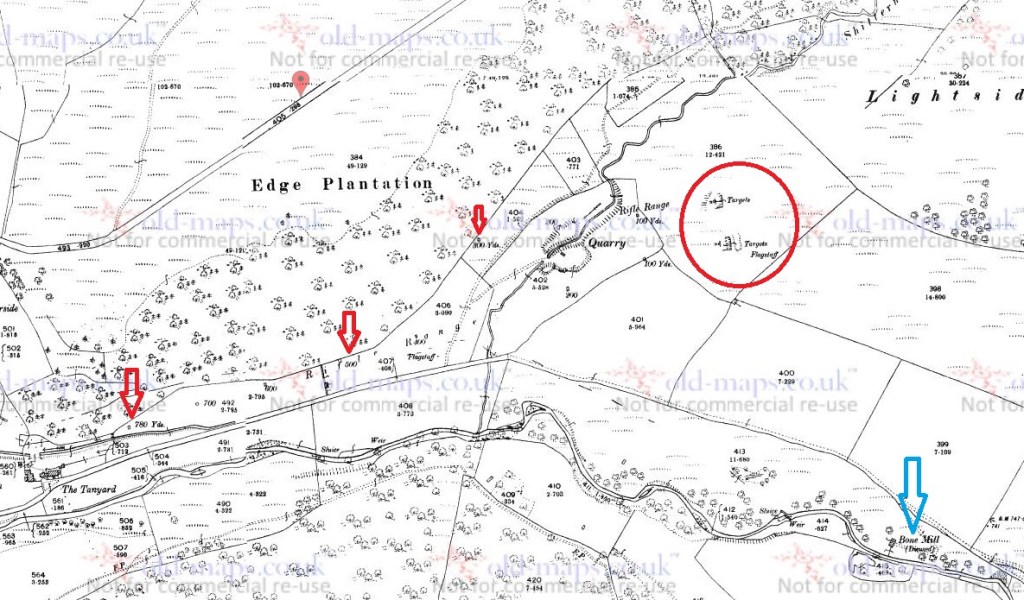

And here it is in 1898:

If you use the What Three Words app, the reference for the quarry entrance is: tribal.workers.crossword

Now, as subjects go, it isn’t perhaps the most interesting, but then as we know on this site more than most, ‘interesting’ is a veeery subjective word. However, it was deemed important enough to have its own Historic Environment Record – MDR10021. Largely overgrown now, and with none of the urgency and noise that would have marked it out as a place of work when it was operating, it is peaceful and still.

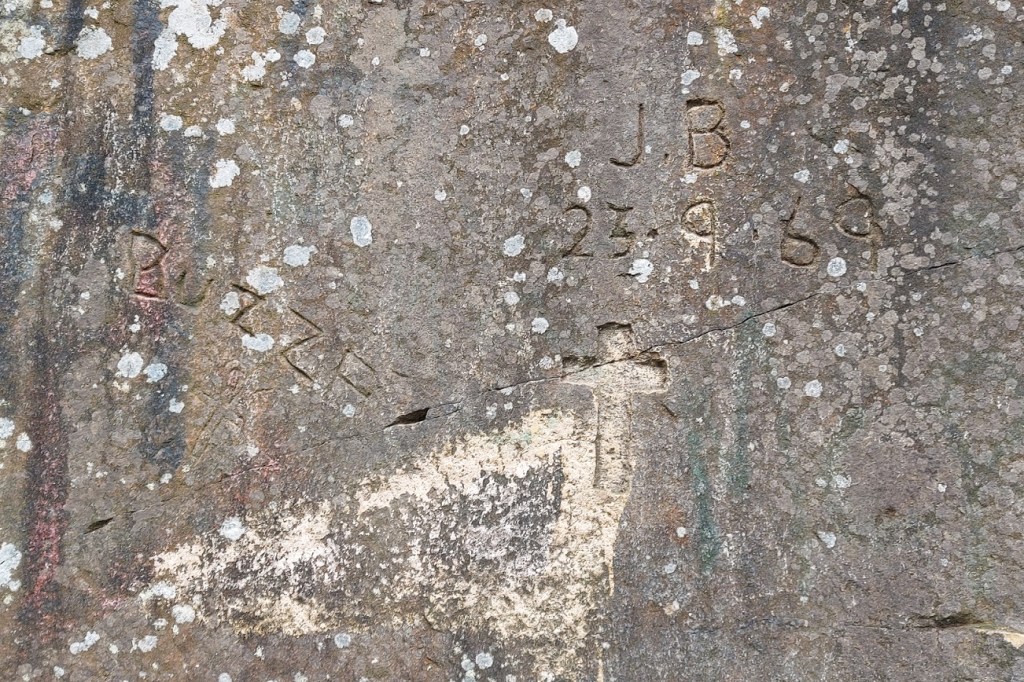

However, the walls are full of interesting graffiti, carved over the years since the place was abandoned. Some is more worthy than others, but all is a record of people, humans being, well… human. I have said elsewhere that there is something universal about the need to leave a mark on the environment, almost a way of achieving immortality, your name living on past you, perhaps. And hats off to those who did it before the invention of spray paint… if you wanted to put your name up in the past, you had to mean it – with a hammer and chisel. Here follows a sample of the carvings – mundane, as well as the more creative.

Talking of symbols, there are what seems to me an unusual number of Christian crosses carved here:

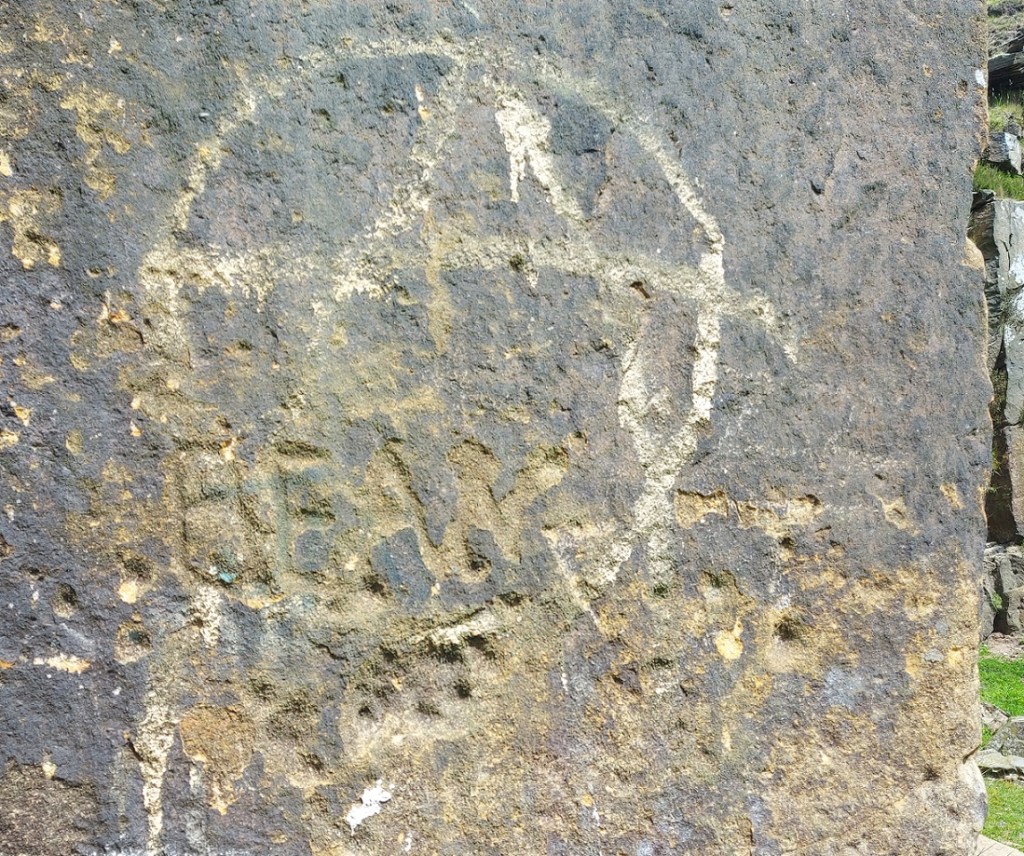

Perhaps it’s the crosses that give the quarry its reputation for Satanism and witchcraft? Anyway, the ‘religious’ iconography culminates in this, what the HER calls “a potential Calvary figure” – that is, Christ on the crucifix:

This is a weird one – is it one figure, or two – a smaller, more feminine and naked, between the Christ-like figure’s legs? Or is it three? The more I look, the less I know. Is that the point? Is there a point? Even down to the almost-altar like outcrop of stone in front of the figure, this is very good.

It seems that this is a modern(ish) rendering, done by a known person – I have heard several different reasons and accounts – and people – but the story is not mine to tell, nor is it for me to name names. That I will save for the comments section, should anyone wish to do so.

However, it looks like it was the same hand that carved this naked lady, as well, so I’m not sure about any religious motivation as such:

There’s also this lower half of a person on their hands and knees.

Moving away from carvings, and back onto the safer territory of history and archaeology, there are traces of the original purpose to which the quarry was put here and there amongst the more modern intrusions.

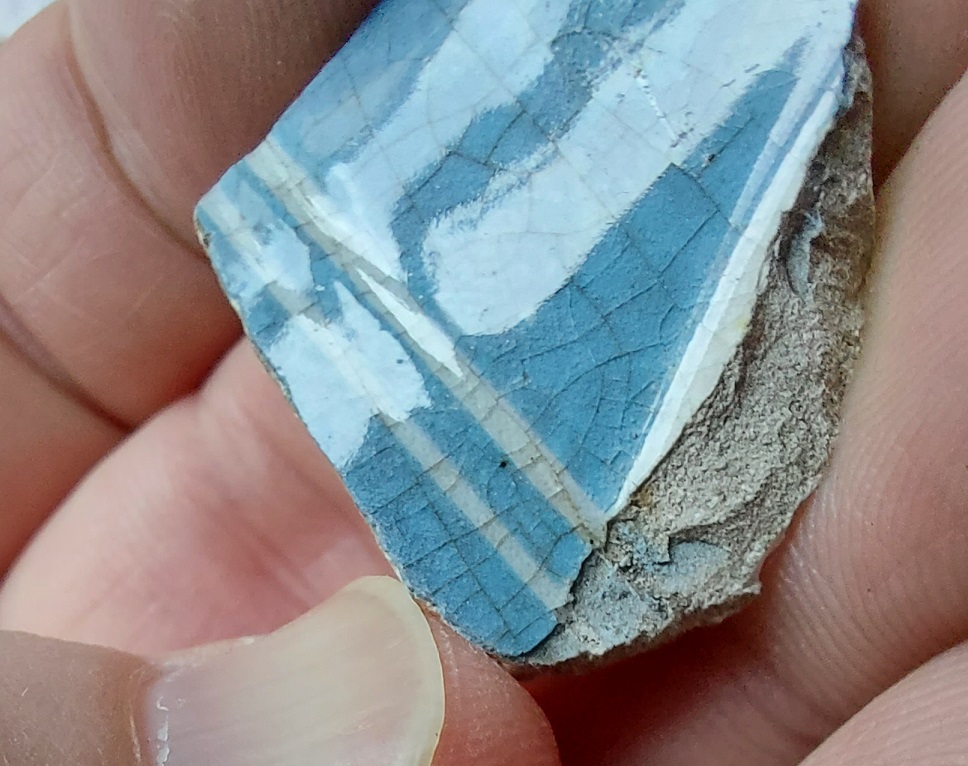

Here we can see the rough dressing of the stone, done prior to it being broken out of the rock face. This provides it with a flat-ish surface before it is smoothed properly elsewhere. This was probably the last thing that was done in this quarry before it was shut down, as it is part of the quarrying process, but was never finished. I like that.

The quarry road is very nicely preserved, but if you look closely at the stone at the bottom of the above photograph, you can see a groove worn into the rock there, running top to bottom. This is the track of a sledge repeatedly being drawn over the stone, day in, day out, for decades. A horse-drawn sledge is easier to use, more stable, and less likely to cause accidents, than a cart, and were often used in these remote quarries.

I also found also a concretion in the rock face of the quarry. Essentially, a concretion is a small boulder of one type of rock which is formed naturally, and which becomes trapped within the matrix of a surrounding rock when it was laid down as sediment millions of years ago.

The concretion erodes at a different rate from the surrounding material, and so they stick out quite clearly. They’re fairly common in this type of Rough Rock, as indeed are plant fossils, apparently, but I didn’t see any of those… I need to go back.

Right, there you have it. More soon – including more pottery, you lucky, lucky, people. I’ve got so many ideas – walks, books, tours, blogs posts, pottery workshops, YouTube shenanigans, surveys, excavations, art, creativity, etc. – and so much I’d like to do. For now though, stay in touch and follow me here, or on Twitter (@roberthamnett), or even on Instagram (timcampbellgreen). Or just come up to me and say “What ho, Robert Hamnett!”.

But until next time, please look after yourselves and each other.

And I remain, your humble servant,

RH.