The thought occurred to me after publishing the previous blog post – what do the names of each of the manors of Longdendale mean? And I thought you, gentle reader, might also be interested.

I find placenames endlessly fascinating, and there is something magical about the origin of a name, whether traced back in the prehistoric period (‘Celtic’ placenames) or of a more recent coinage (Victoria Street, for example, named after Victoria Wood, of course…). Moreover, once you name a place it becomes familiar, and less scary, allowing you to find your place within, and manoeuvre your way through, the landscape. It is also a fundamental aspect of human behaviour: by naming the land, you are taming the land.

We have a huge number of influences in placenames in this area: Celtic, Saxon, Norse (Viking), Norman French, vernacular and slang English, and Welsh, to name a few. All of which mix together to create the landscape, and the places within, we know so well.

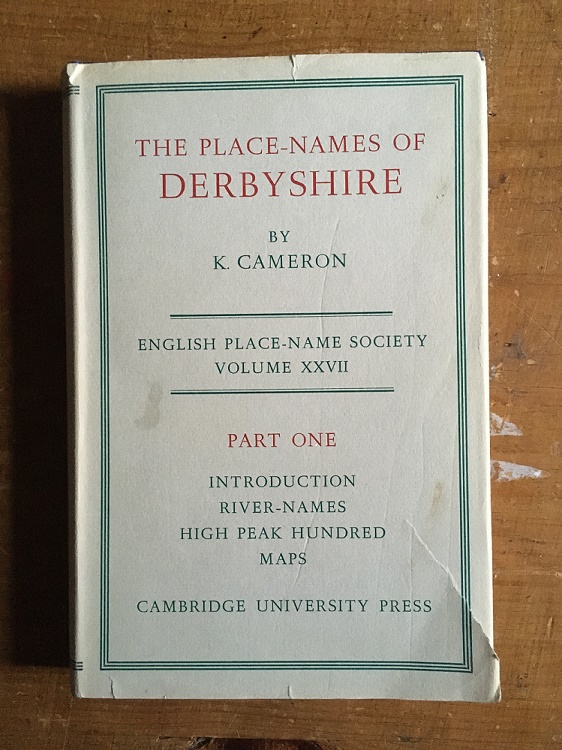

So then, using the 3 volume set of The Place-Names of Derbyshire by Kenneth Cameron, and some other sources, I set about finding out.

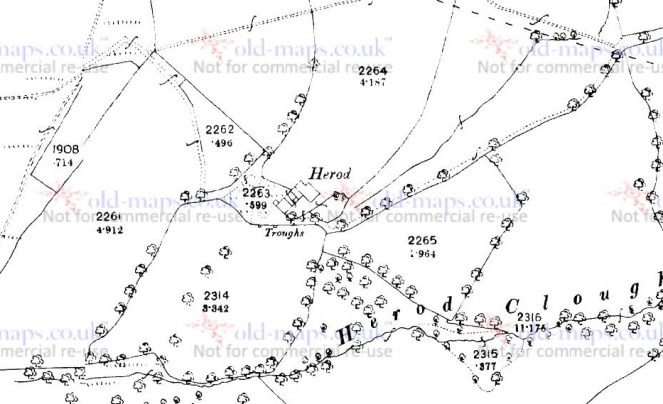

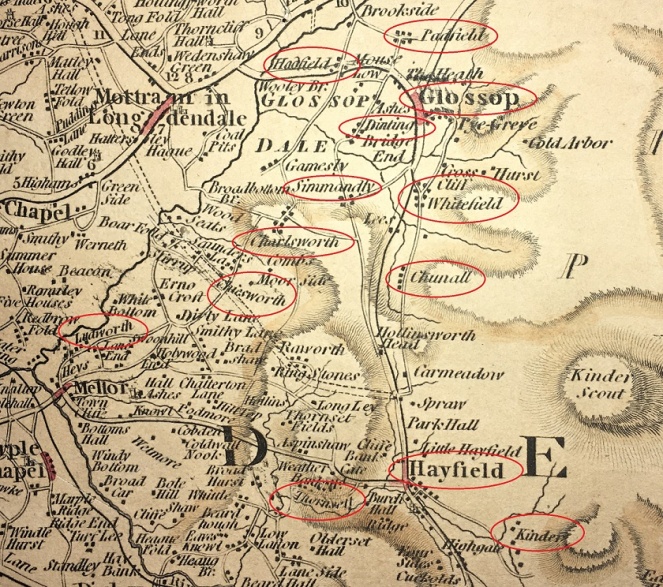

- Longdendale

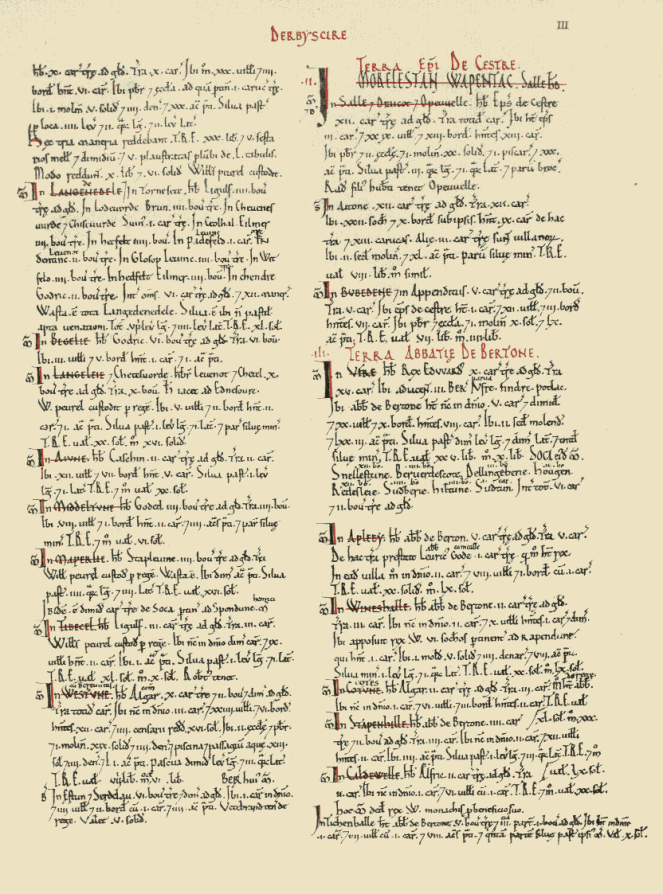

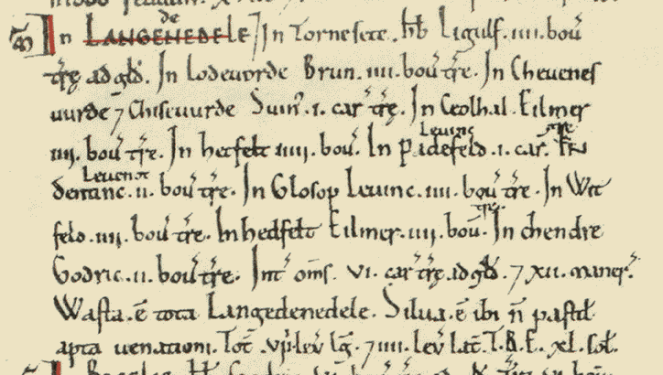

First mentioned in Domesday Book of 1086 as Langedenedele, then Langdundale (1158), and Langdaladala (1161). This is a classic example of a tautology, caused by the naming of a place by someone who didn’t understand the original name. The origin is Lang Denu, ‘the long valley’, to which at some stage someone added the unnecessary ‘Dael‘, meaning ‘valley’ – thus Longdendale means ‘the long valley valley’.

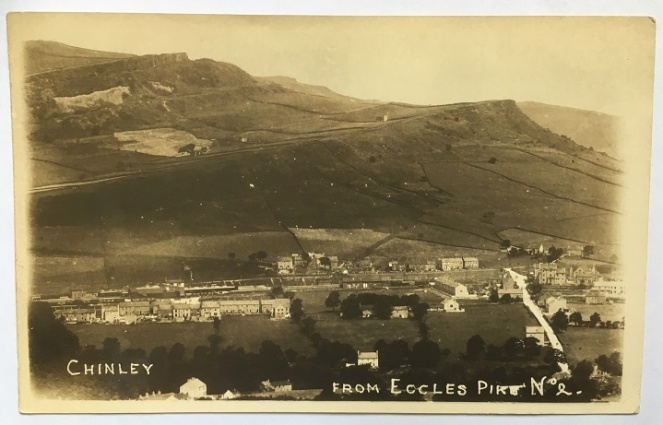

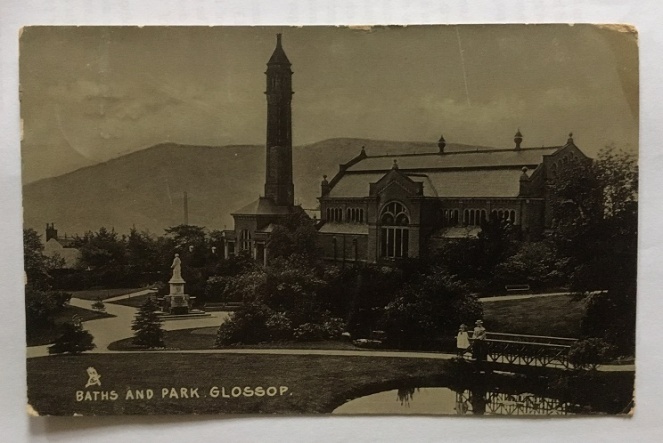

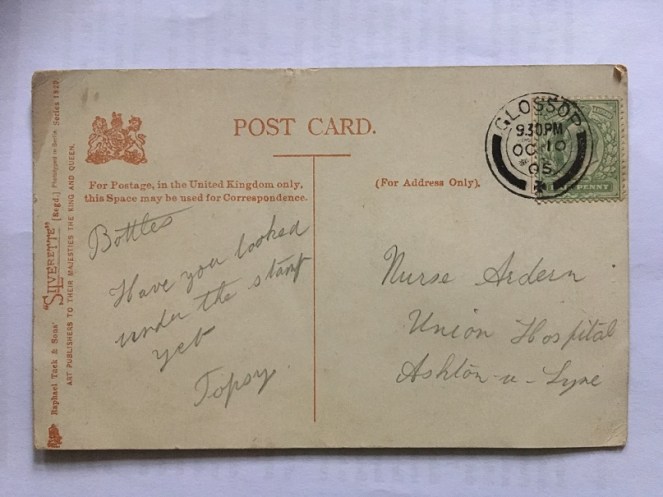

- Glossop

First mentioned in Domesday as ‘Glosop’. The Book of Fees of 1219 records it as ‘Glotsop’, and in 1285 it is given as Glosshope. Cameron gives the etymology as Glott’s Hop – Glott’s Valley – The valley (Hop – think Hope, as in Hope Valley) belonging to a man named Glott. Relatively straightforward then. Probably. Other theories are available. Mike Harding, the folk singer, thinks Glott should be read as ‘Gloat’, in which case it is the ‘Valley of the Gloater or Starer’, a reference to the numerous carved stone heads that were, and still are, relatively commonly found in the area (a subject of much debate, and a future blog post). This seems a little too convenient and smacks of mystical wishful thinking, but is still worth considering. It is also a possibility that ‘Glos’ is a derivation of the Welsh ‘Glwys’, meaning silver or grey, in which case it would mean ‘Valley of the Stream called Glwys”, which presumably would be Glossop Brook. Ultimately, I am going to go for Cameron’s ‘Glott’s Valley’ as I think it makes more sense.

- Charlesworth

First recorded in 1086 in the Domesday Book as Cheuenwrde, then as Chavelesworth (1285), Chasseworth (1285), and Challesworth (1552). The meaning is either ‘Ceafl’s enclosure‘, the enclosure (worth) belonging to a person called Ceafl, or ‘Ceafl enclosure‘, which would mean ‘the enclosure near the ravine (ceafl)’. This might conceivably refer to the valley of the Etherow, particularly as it nears Broadbottom, but it is unclear. On balance, I prefer the simple ‘the enclosure (worth) belonging to a person called Ceafl’.

- Chisworth

First recorded in 1086 in the Domesday Book as Chiswerde, then as Chisteworthe (1285), Chesseworth (1285), and Chesworth (1634). The meaning is simple – ‘Cissa’s enclosure’, the enclosure (worth) belonging to a person called Cissa.

- Hayfield

First recorded in 1086 in the Domesday Book as Hedfelt (the same as that at Hadfield below), then Heyfeld (1285), Heathfeld (1577), and Magna Heyfeld (1584 – as opposed to Little Hayfield). Cameron discusses the possibility that there is some confusion regarding this name. In the Domesday Book the meaning is ‘Haed Feld’ – ‘heathy open land’, but the later, Middle English, forms seem to suggest ‘the field where hay is obtained’. Actually, I would suggest that two aren’t incompatible as land use may have changed over the course of 300 years – it is no longer heathy, and instead is more, well, hay-y.

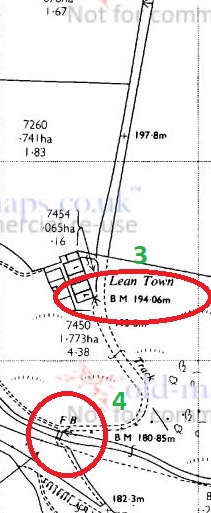

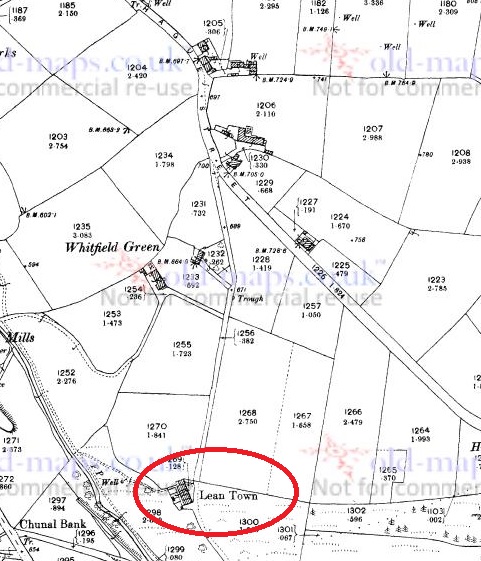

- Chunal

First recorded in 1086 in the Domesday Book as Ceohal, then as Chelhala in 1185, and Cholhal in 1309. The origin is Ceola Halh, which means either the ‘the neck of land belonging to a person called Ceola’ or ‘the neck of land by the ravine’. I personally favour the latter, with the ravine here being Long Clough Brook.

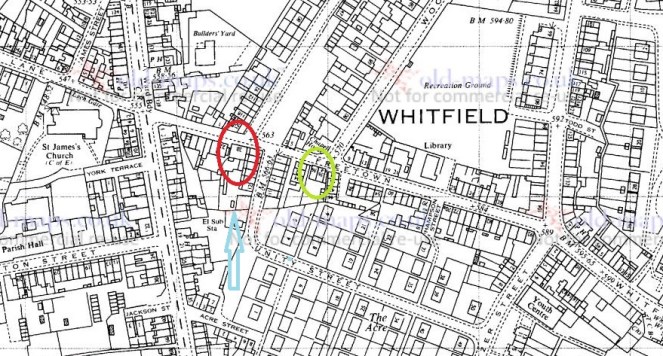

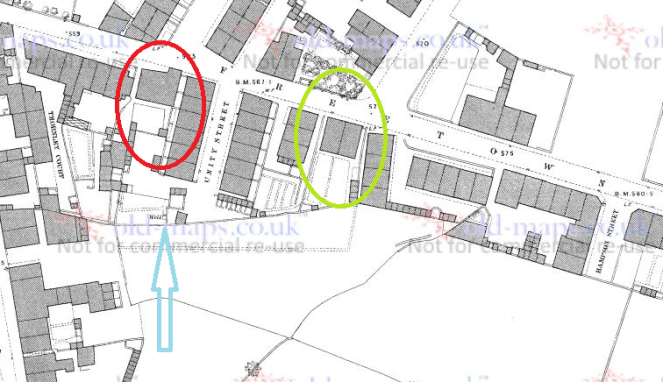

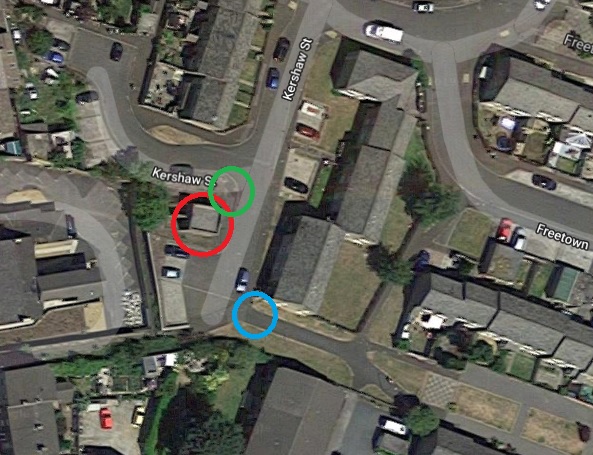

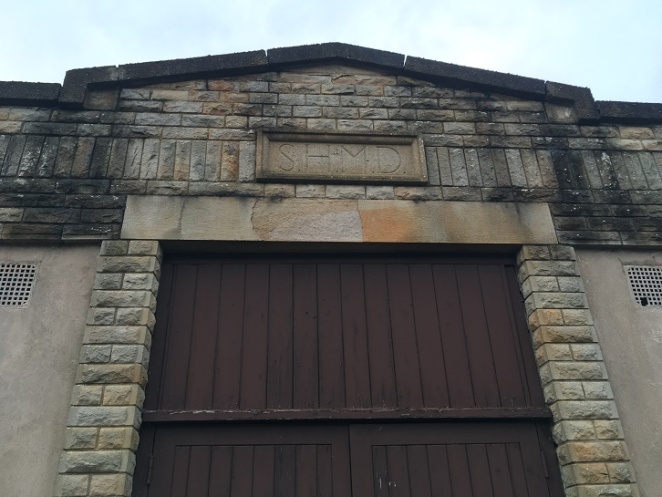

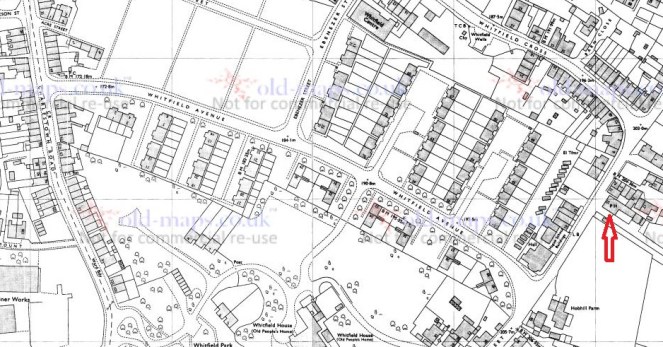

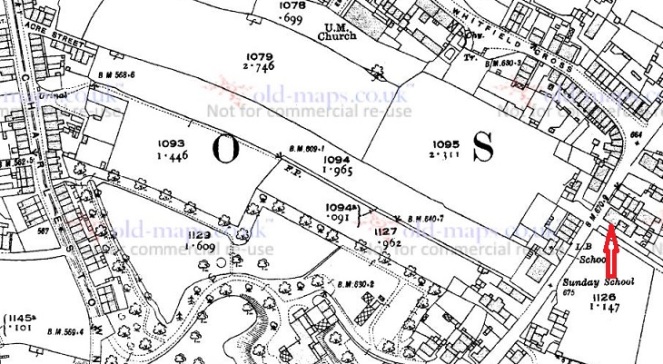

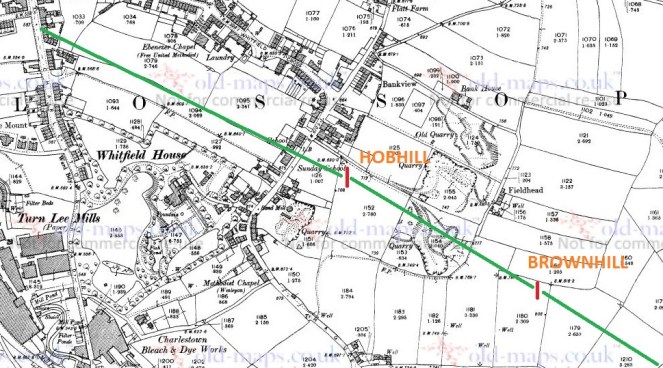

- Whitfield

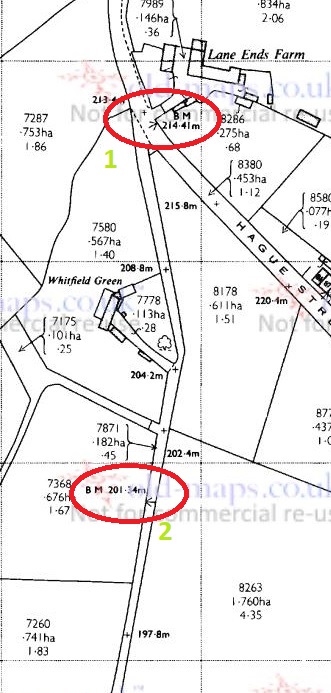

First recorded in 1086 in the Domesday Book at Witfelt, then as Wytfeld (1282), Whitefeld (1283) and Whytfelde (1294) in various Inquiries Post Mortem. It is also recorded as Qwytfeld in a land deed of 1424 pertaining to one John del Boure (Bower) of Qwytfeld. The meaning is ‘Hwit Feld‘ – open (figuratively ‘white’) land or field, presumably to differentiate it from the surrounding moorland.

- Hadfield

Relatively straightforward, this one. First recorded in 1086 as Hetfelt, and later as Haddefeld (in 1185), Hadesfeld (in 1263), and Hettefeld (in 1331), it is derived from ‘Haed Feld’, meaning ‘heathy open land’ – literally, a heath field.

- Padfield

Also relatively straightforward. It is first recorded in the Domesday book of 1086 as Padefeld, and in 1185 as Paddefeld. It means either the ‘open land (feld) belonging to a person called Padda‘, or an ‘open land where the toads live’, from the Old English ‘Padda‘ meaning toad. I like toads and frogs so I’m going with that, but you decide as you see fit.

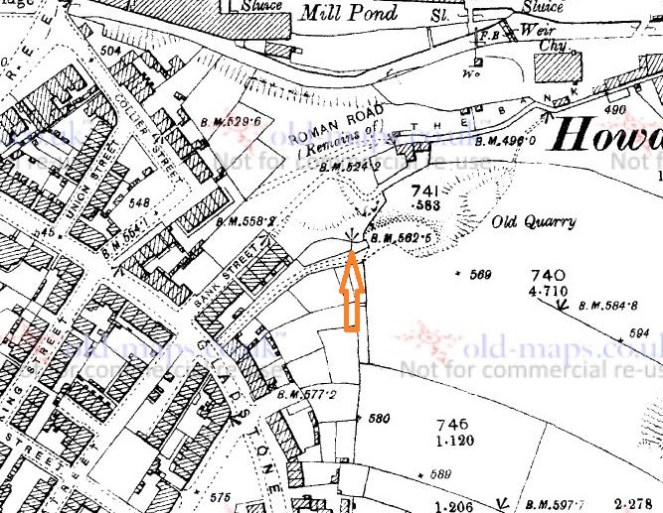

- Dinting

This one is more difficult. First recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086 as Dentinc, and then Dintyng in 1226, and Dontyng in 1285. It is also almost certainly the Dontingclought (Dinting Clough or Dinting Vale, as we now know it) mentioned in the Forest Proceedings of 1285. However, the meaning of this name is difficult to uncover. Cameron suggests that the first part of the word “Dint” is Celtic in origin, but can offer no meaning for the word. The second part ‘ing‘ is commonly encountered, but is complicated as it has many possibilities in its meaning. Here, it either means the ‘place of the Dint‘ (whatever Dint means), or it denotes an association of a person to the place or feature, so here it would be ‘Person X’s Dint‘ (again, whatever Dint means). The other (original… real) Robert Hamnett suggests that the name is made up of two elements – the Celtic word ‘Din‘ meaning ‘camp’, and the Norse ‘Ding‘, meaning ‘council’, thus it means the ‘council camp’, or a place where people meet to discuss law and other matters. Perhaps then we have our meaning – ‘the camp belonging to person x‘, or the ‘place of the camp‘. This latter may well be more likely, given that Dinting as we know it is at the foot of Mouselow Iron Age hillfort.

- Kinder

This one is similarly difficult to pin down. First recorded as Chendre in the Domesday Book, then Kunder in 1299, Kynder and Kyndyr variously in the 13th and 14th centuries, and Chynder in 1555. Cameron suggests the name is “pre-English”, that is pre-Saxon and thus probably Celtic. He offer no explanation for its origin, as the “material is not adequate for any certain etymology”, alas. Still, the fact that the name is essentially Iron Age in origin is quite important.

- Thornsett

First recorded in 1086 in the Domesday Book as Tornesete, then as Thorneshete (1285), Tharset (1577) and Thorsett (1695). The meaning is very straightforward – Thorn Tree Pasture.

- Ludworth

First recorded in 1086 in the Domesday Book as Lodeuorth, then as Ludeworda (1185), Loddeworth (1285), and Luddeworthe (1330). The meaning is very simple – Luda’s Enclosure, the enclosure (worth) belonging to a person called Luda.

That concludes the 12 manors of Longdendale. However, I thought I’d also include Simmondley – even though it’s not one of the original 12, it is one of the towns that make up Glossop as we now know it. Plus, I know people who live there and don’t want them to feel left out.

- Simmondley

First mentioned in the Forest Proceedings of 1285 as ‘Simundesleg‘, and then later as Simondeslee, the origin of the name is “the clearing (or ley/legh) in the forest belonging to a man named Sigemund or Sigmundr (an Old English or Scandinavian [Viking] name) – Sigemund’s Legh = Simmondley.

And there you have it.

Well that was fun! I’d like to do some more exploring of names the area; we have a rich tapestry of placenames in England, brought to us from hundreds of different sources, and recorded in countless documents, maps, letters, deeds, books, and memories, and this area seems to be richer than others. So if you enjoyed this, then watch this space. As always comments, questions, offers to buy me a drink, are all welcome.

And as always, I remain,

Your humble servant,

RH