What ho, one and all! We are still in the bleak midwinter, but I trust you are all bearing up under the strain. I am actively shivering as I write this, and I might have to light the fire… and have a glass of the stuff that both cheers, and warms.

So then, this unexpected article presented itself through the extremely unlikely medium of a 9-year-old schoolboy! Actually, and to be fair to him, if you knew this particular 9-year-old, you wouldn’t find it that unlikely; he is one of those wonderful creatures that infests a school, creating mischief and chaos, and which forces you to tell him off. And yet he makes the day – and the job – so much more enjoyable, precisely because of the mischief and chaos, and because he is a thoroughly likeable chap. Stand up and take a bow Stanley, you marvellous man, you!*

At 8.55am, he bounces down the corridor towards me with a wide grin. “Good morning S, old bean” I hail. “Morning Dr CG” he replies “I’ve got something in my bag for you“. As opening gambits go, it’s a good one… I’m intrigued. “Shall I get it?“. “Ooooh, nice…” I say (slightly worried though, I know his mother… and the whole family, and frankly it could be anything in his bag). “No, wait until break time“. Break time arrives, and clutching a handful of something, he sought me out. Carefully wrapped in tissue is the subject of today’s article, and wonderful it is, too. Apparently, he found it on a Victorian (and later) rubbish dump, with his parents, and in a whole condition (remarkable in itself). However, the night before he had knocked it off a shelf in his room, and it now lay in three perfect pieces in the kitchen paper in front of me. Knowing that I’m archaeological, and somewhat pottery obsessed, he wondered if I might have some magic to work to fix it. And indeed I did (UHU yellow glue, and a cocktail stick, since you ask… remind me to show you sometime).

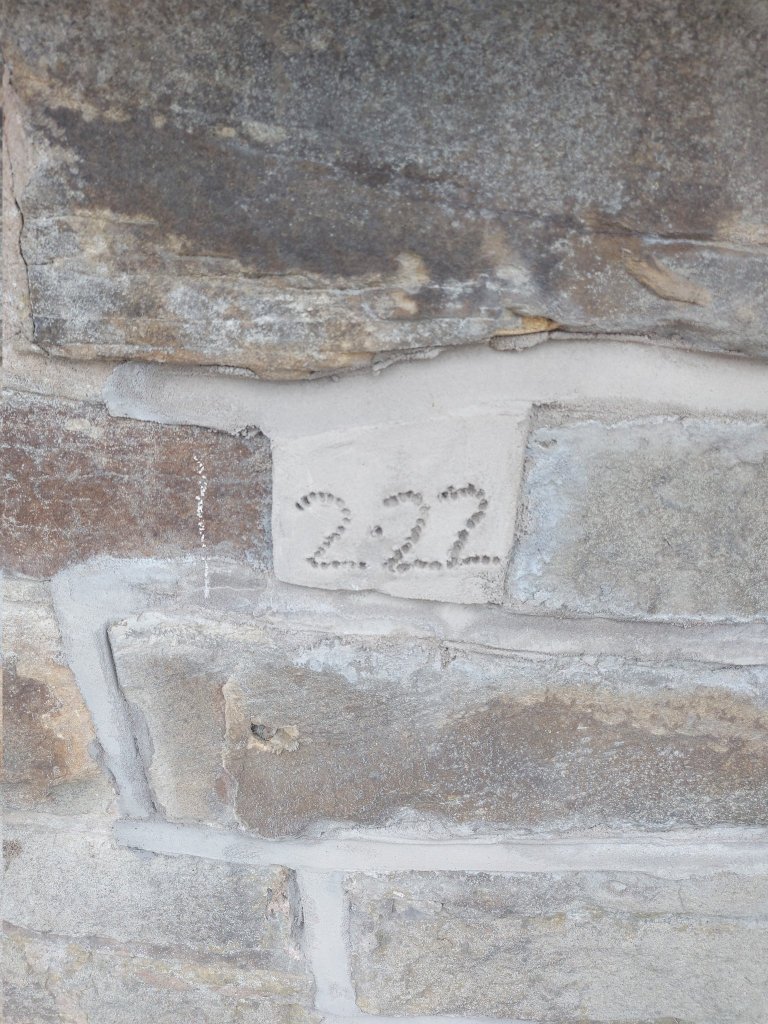

So then, it’s a mug. Blue and White transfer printed, and not particularly high quality. Victorian, I guessed. Biggish, but not huge, and not very refined in shape or small in size – 9cm in diameter – so didn’t immediately strike me as a tea cup… just a mug. Here it is:

However, as I was inspecting the results of my mending, I noticed a few things that make this mug special, and immediately alarm bells began ringing – “I say! Here is a great article for the old website!” I thought, and, well… here is the very article.

Here is the mug from a variety of jaunty angles, to give a better idea of the decoration:

So then, a fairly standard blue and white transfer printed vessel (follow the link for more about Blue and White, and how it was made). Poor quality, I’m not going to lie – the blur at the top of the 4th photo above is not the result of my terrible camera work! It’s a smudge and a mistake on the part of the person applying the transfer. I mean no judgement by that – it was probably their (likely her, as it was largely a female job) 1000th transfer application that day, and with just another 1000 to go before a break. Incidentally, the brown spots on the exterior are the result of the mug lying next to something iron in the dump, and as the iron oxidises and rusts, it discolours the surface.

The actual standard of the transfer is poor too – I’m by no means an expert in this stuff, but it’s not a top notch engraving. It’s also not a standard willow pattern – it is ‘Chinese’ inspired, but not the tale of the two lovers changed into birds, etc. Instead, it is a pile of pagodas, Asiatic trees… and weird fish people, walking on their tails, and attempting to do the conga over a bridge. Which is… different.

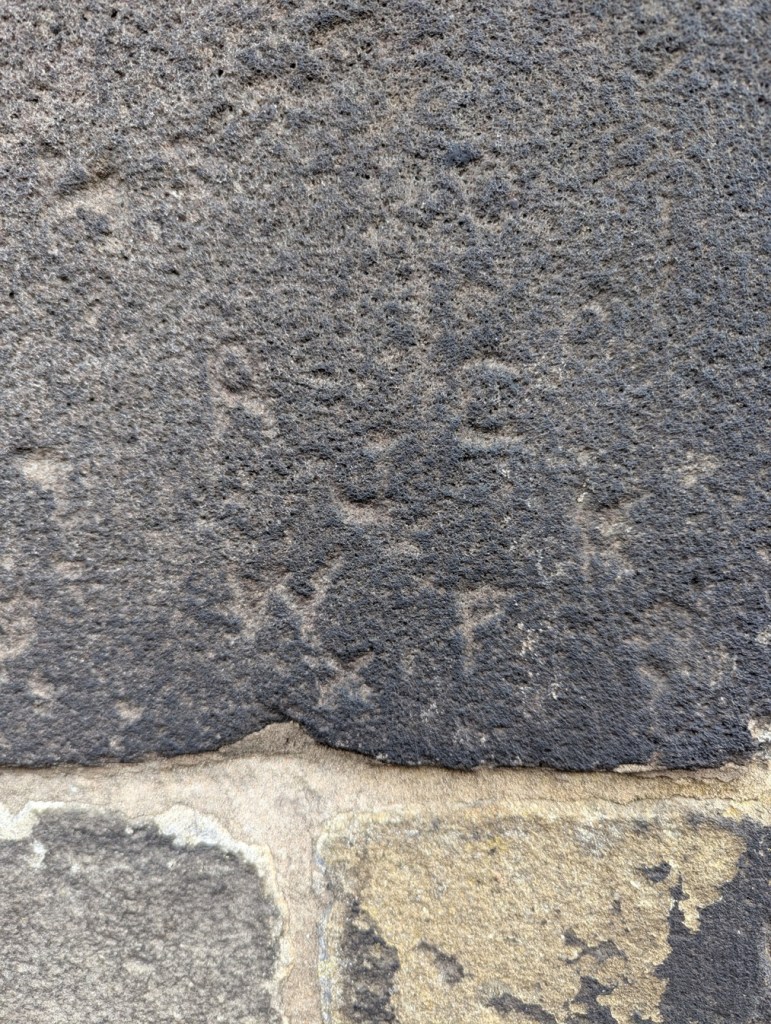

But it was this I noticed on the exterior that set me running to the website:

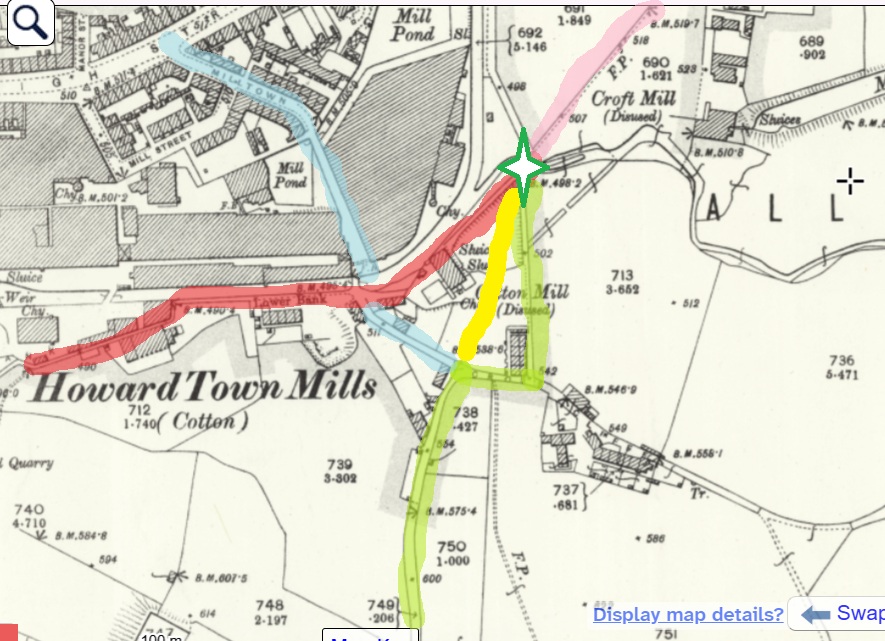

It’s the word “Pint” over a crown, with the letters “G R” below, and over the number “76”. Now where have I seen something like this before? Oh yes… on every pint of beer I drank in a pub until 2006. It is the official Weights and Measurements Crown Stamp Mark, placed on every glass and mug used in pubs to ensure we are not sold a short measure. Originating in the Victorian period, after 2006 they were replaced by a CE mark, ensuring conformity to the EU standards, which in turn was replaced by a UK standard in 2021 following Brexit.

“Pint” indicates the measurement, “GR” is the regent – in this case “Georgius Rex” – King George V or VI, and the number “76” refers to the Weights and Measures authority in Salford and Manchester. George V or VI reigned one after another from 1910 to 1952 (with the very brief – 9 months – reign of Edward VIII in between), and in this case the royal cipher refers to George V, who reigned 1910 – 1936, providing us with a lovely date for when the pint pot was in use. As to which pub it was used in, alas, I cannot answer, but the fact remains that at some time between 1910 and 1936, in a pub in Glossop, people drank beer from this mug. And actually not for long, it seems – there is very little wear on the base, indicating it was in use for a short time only, and then it was thrown away whole, rather than after it was dropped and broken into pieces. That’s an odd thing to do, but I think I know why. Looking closely, there is an old hairline fracture – discoloured by the soil – and starting from this minor chip on the rim; I wonder if it was dropped or banged – enough to cause damage but not enough to fragment it?

The pub, seeing the damage, chucked it away into the dump, only to be dug up 100 years later by the aforementioned schoolboy. It also has the makers mark on the base, which gave me another tingle!

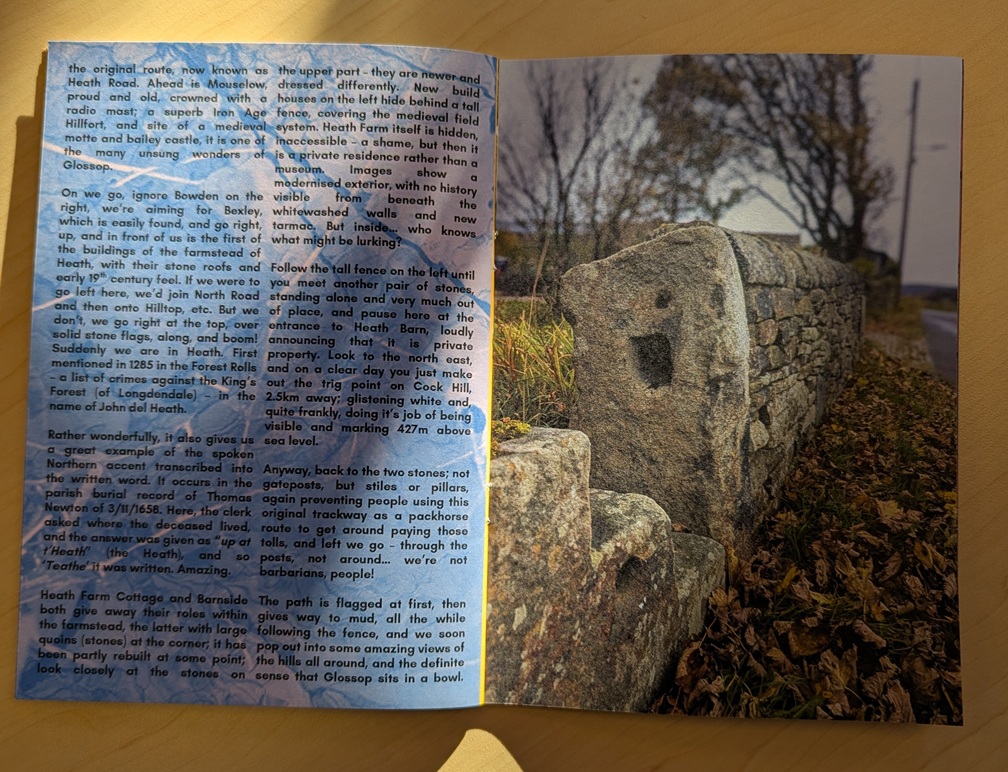

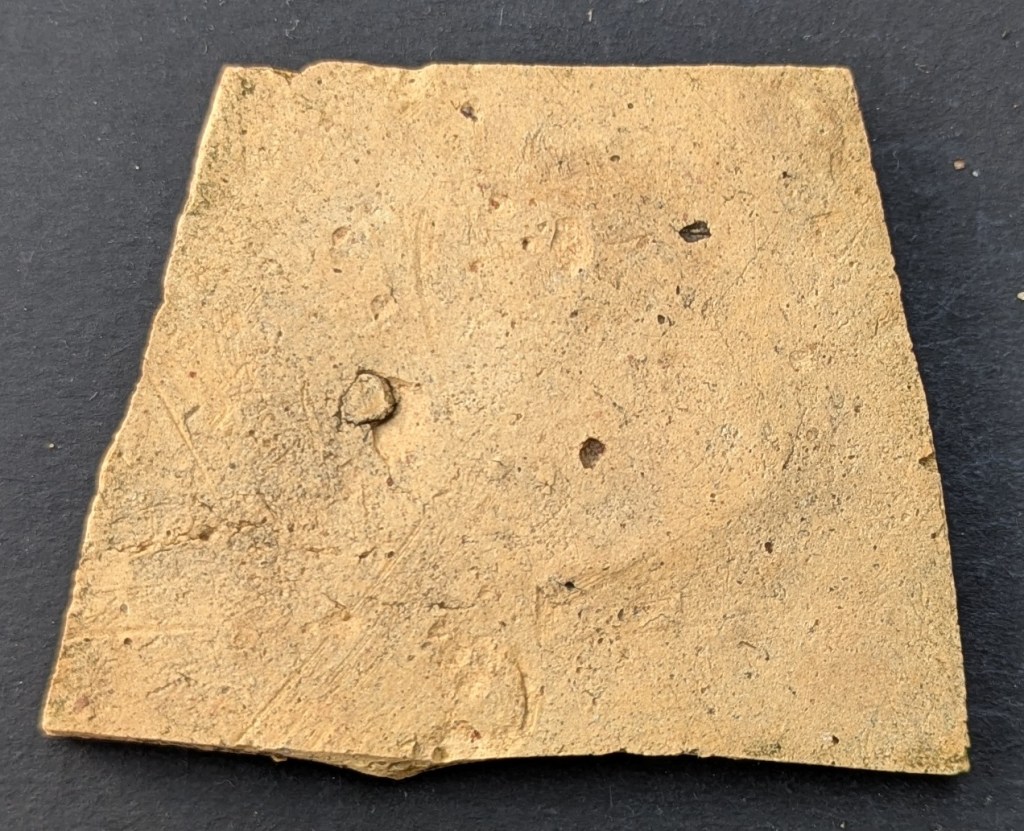

With the eye of faith, squinting, and on my third glass of stuff that cheers… it reads “Semi China”, and says “W A and Co” around the bottom of the lozenge. Presumably the other letters refer to the shape, and decoration type, etc. Anyway, it was a lead, and something to chew on.

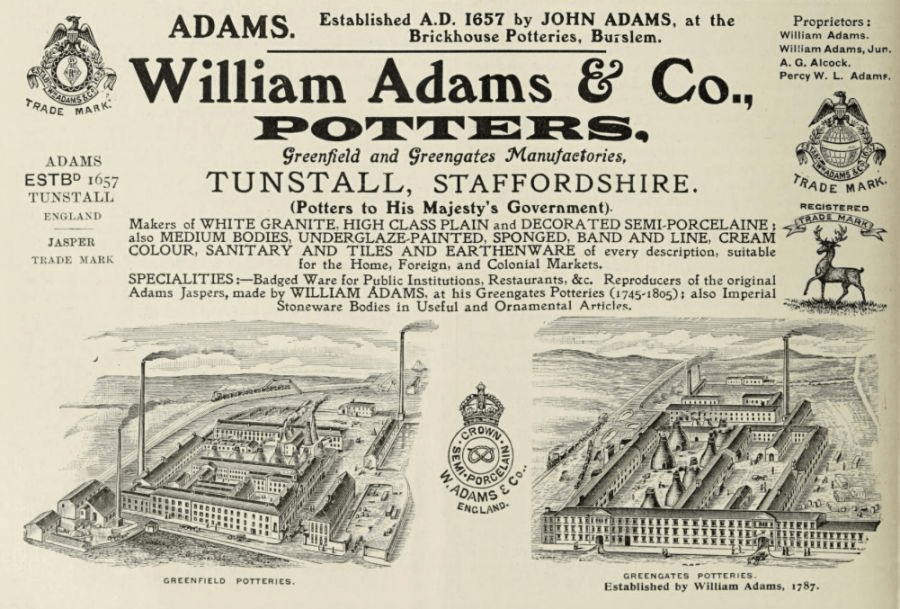

“WA and Co” is William Adams and Company, a pottery manufacturer that operated between 1657 and 1966 in the heartland of the Staffordshire Potteries.

They specialised in making, among other wares, ‘Semi China’ – a cheaply produced alternative to Bone China – it’s earthernware, but cleaner and whiter. The company was eventually taken over by Wedgewood, and stopped manufacturing by the 1990’s.

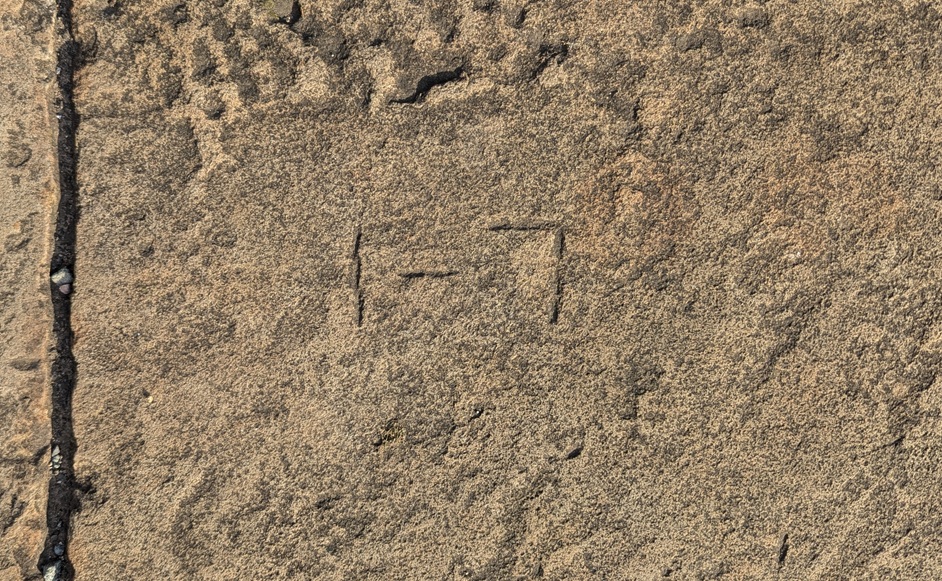

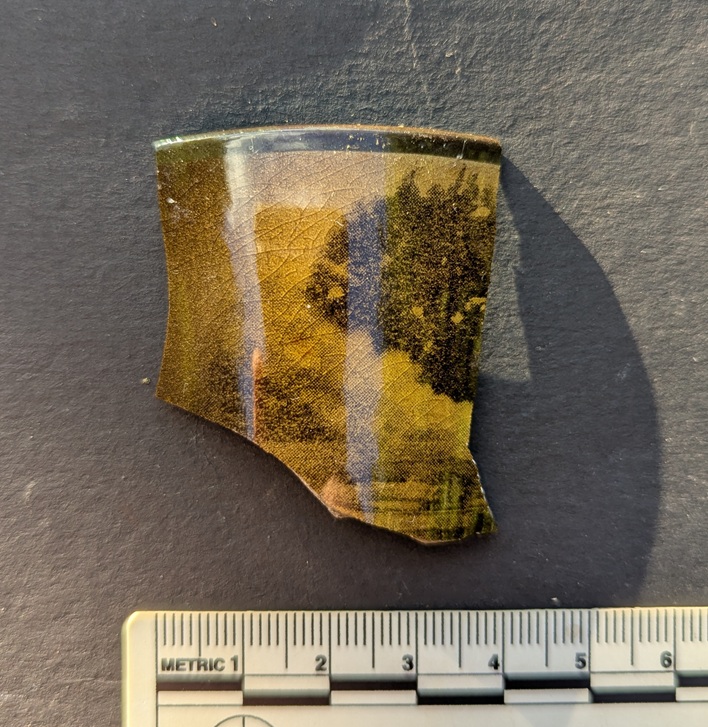

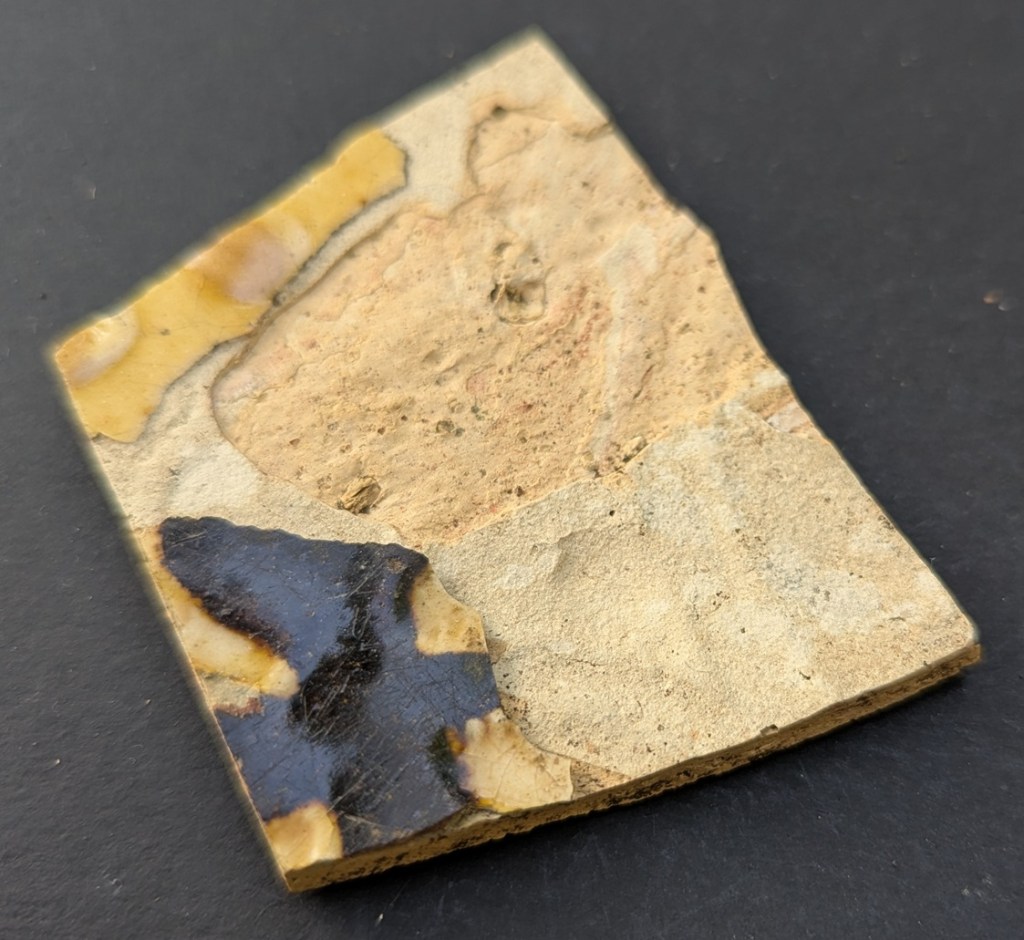

Also connected with manufacture are these marks on the base:

Three smudged holes in the glaze in shape of a perfect equilateral triangle, and a sneak peak into the way the mug was fired. When a glaze on the outside of the mugs surface is fired, it becomes a liquid glass, and then cools into the shiny surface. However, if this surface comes into contact with another mug, pot, or even the kiln wall, it will fuse onto that, essentially melting into a lump. in order to prevent this, objects to be fired are stacked in a particular way, and are separated by what’s known as ‘kiln furniture’, in this case a ‘stilt‘, which provides the minimum amount of contact between pots – simply three tiny points. The mass production of these cheaply produced vessels meant that the stilts are reused to the point of them being knackered, and less care taken – hence the wide jagged holes. However, stilts are used even on the finest pottery, only you can’t see the holes so easily.

So there we have it, a 1920’s pint pot from a pub in the Glossop area.

Right, that’s all for this time. There’s lots going on at the moment, but I couldn’t let a great post like this just wait! I want to thank Stanley for this article, though – it’s all his. The mug itself is now ‘safely’ back in his hands – a truly wonderful piece of history, loved, and back on the shelf. Thank you, S old bean… see, I told you I’d put it on the website and make you famous!

Until next time, look after yourselves and each other, and I remain.

Your humble servant,

TCG

*For the record, I cleared it with his parents before publishing this article – thanks Emily & Ant, & E!