What ho, and, if I might say, a happy new year to you all!

A somewhat chaotic mixed bag this week as its essentially a series of updates of previous posts. But fear not gentle readers, there is pottery here, too. Oh yes, don’t you worry about that. On with the show, then…

A SPOON

A while back I received a strange gift in the form of a spoon left on the wall outside my house. I blogged about it here, but here is a reminder:

I noted that the numbers might have been a way to prevent the theft of the spoon from the Beehive pub. Well now, that’s clearly nonsense, and I have been something of a blockhead (I said “blockhead“, thank you very much), and it took the wonderful Sandra T to point out what should have been obvious – they are military identification numbers, corresponding to an individual soldier.

So I did a little digging (a poor pun, fully intended… please accept my apologies), and indeed it is a WWI military issued spoon. The makers – Walker and Hall of Sheffield – and the spoon design, both check out; millions of this type and design were issued to soldiers, made by a variety of manufacturers. The date of roughly 1880-1920 similarly checks out. Now, the markings. It should be noted that there is no ‘Broad Arrow‘ mark on the spoon, which is something that was put on anything related to the military. This is unusual, but not unknown – an individual spoon maker, hand stamping thousands of these things a day, is bound to make a mistake or two – or it may well have been a replacement spoon for one our man lost. The Service Number is the interesting part, as it could potentially identify the man himself – a name to a spoon, so to speak – and give us a little history. Alas, they are jumbled, with some seemingly upside down, and so far I have not been able to identify the person that used them. They seem to read:

5 4 6/9(upside down?) 6/9(upside down?) 3(upside down) 2

I may be wrong, and please, feel free to have a look yourselves – I’d love to give a name to the owner.

One final aspect of the spoon convinces me that this it is a WWI issued: the shape of the bowl. I had thought that the lob-sided nature indicated use-wear by a right handed person, but according to this forum, inhabited by all sorts of experts, it was deliberately done by many soldiers in order to enable the standard rounded spoon reach the more square corners of a mess tin. So there you go.

As to why it was in a wall… I don’t know. It may simply have been mischievous or bored activity – pointless and mindless, but something we have all done. But it feels more purposeful, and I am reminded of the blacksmith in the village of Catwick in Yorkshire, who nailed to the doorpost of his forge coins given to him by the 30 soldiers from the village going off to war, all arranged around a horseshoe. The coins represented each of the soldiers, leaving a little of themselves in their rural home, and the horseshoe luck. This can be considered an act of sympathetic magic, however half-hearted or jokingly done, conjured by a blacksmith, an individual who folklore already imbues with magical power. Interestingly, Catwick is one of only 53 villages in England known as ‘Thankful Villages‘ in that every man who went off to war, came back alive. Perhaps the magic worked? Was our spoon perhaps placed in the wall by our man as a way of leaving something of him behind, in order that he would return unharmed? And if so, did it work I wonder? I hope it did.

DATESTONES

So, the great datestone list has expanded… by three for Whitfield, and several more for surrounding areas. I’ll stick with Whitfield for now, though.

Pikes Farm, then. A date of 1780, and the intitials S. W. which, according to the original Robert Hamnett, belong to Samuel Wagstaff. And who are we to argue with that. I like the flourish with which the ‘8’ has been carved, not completed so that it looks almost like an ‘S’. Pikes Farm is interesting; it sits on the line of the Roman Road from the fort of Navio at Brough, near Castleton, and was connected by trackway to Dinting and Simmondley. It is such a prime location that I find it difficult to believe that people waited until 1780 to build a farmhouse there, and I suspect the location is a lot older.

Alas, no photograph. It is set far off the road, and although I tried, my phone’s zoom is not great. And strangely, people take a dim view of random Herberts wandering over their land and taking photographs. So instead, like any other sane and normal person, I sat in the car on the road and, using binoculars, I drew the datestone (…and that, Your Honour, is what I was doing when police Constable Jones wandered over.) . The date is 1772, the letters are R S M W – perhaps Robinson? Not sure, and Mr Hamnett can’t help us here, alas.

This next datestone illustrates why caution is sometimes needed in using datestones

Whitfield Barn is on Cross Cliffe, the old trackway. As the name suggests it is a converted barn with probable farm house attached (another example of a ‘laithhouse’, that is a building made up of a house, barn, and byre/shippon in one). The stone is modern, and whilst the building is old (1750 – 1800, say), it doesn’t look like one built in the mid 17th century. Now, I’m not suggesting anything is incorrect, and it is likely that the building has a core that is of that date, and that the owners simply had a stone carved to reflect that. Indeed, if you look closely, you can see a number of different building phases. In particular just below the roof, where the upper floor has been raised, you can see the original roof line marked out in a line of stone.

However, what if the owners were incorrect and mis-read an old deed? Or worse, anyone can commission a stone to be carved with any date they fancy. I’m certainly not saying that this is the case here, just using it to illustrate that there can be problems if we rely on a stone for a face value date. However, if we take that date as legitimate (which I am sure it is), then it provides us with a handy terminus ante quem for the track – the track goes past the house not to it, which implies the house was built after the track, so the track must already have been there in 1657.

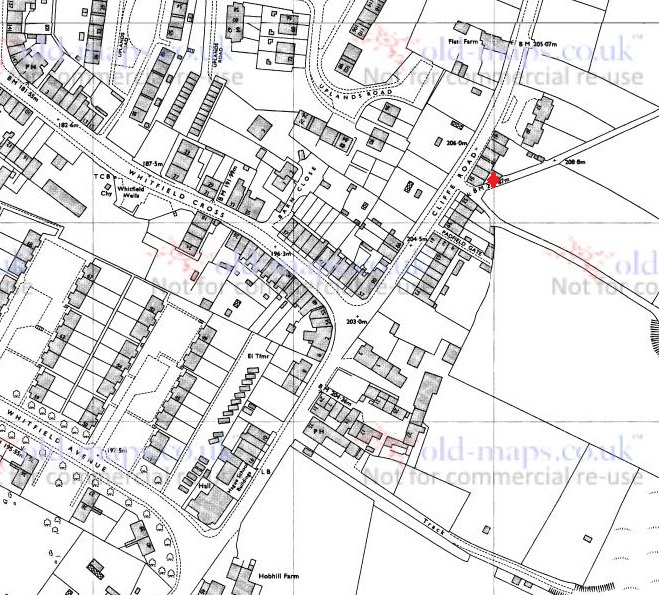

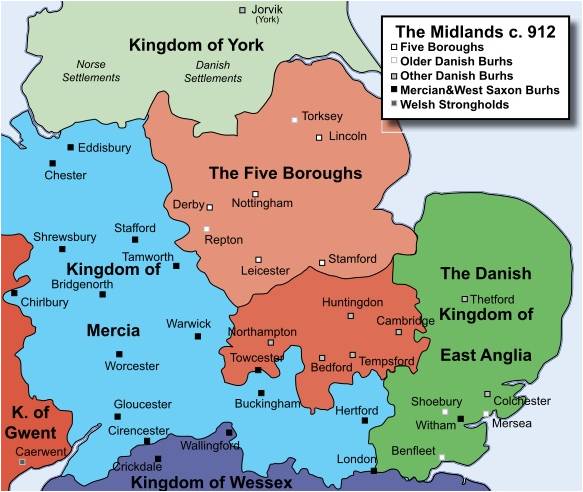

I think these local tracks are largely medieval in date, and form a network that enabled people to move between the settlements that made up the Glossop dispersed settlement. And as time went on, more land was freed up, and new farmsteads sprang up along these routes. Thus, along this trackway that starts in Whitfield at the bottom of Cliffe Road, we see Whitfield Barn, Carr House, White House (with a side track taking in Jumble and Lower Jumble Farms). And, it follows, if we know where the original destination was, we can suggest an early date for that. The answer here is The Hurst on Derbyshire Level. Hurst is from the Anglo Saxon Hyrst, meaning ‘wooded hillock’, and which probably describes the hill immediately south-east of The Hurst. It is first mentioned as Whytfylde Hurse in the Feet of Fines in 1550, but an earlier date might be suggested by the rounded or ‘lobate’ shape of surrounding fields, indicative possibly of assarting (the process of converting forest into arable land), and what, to this untrained eye, looks very like ridge and furrow in the fields surrounding it. Both of these are largely medieval practices, and together could be quite telling. Hmmmmmm… I think The Hurst area needs a bit more looking into!

A CARVED CROSS

I blogged about a mystery white stone with a cross carved on it ages ago. I suspect that it (the stone, not the cross) is to protect the house from horse-drawn traffic, but why it has a cross on it, I still have no idea. Some months ago, though, I was sitting having a pint at the Beehive waiting to meet Mrs C-G, and vaguely staring at the wall ahead of me (I do love a nice bit of old walling!) when suddenly this came into focus:

Given that it is on the same road, not 100 yards from the white stone, and carved in the same rough but deliberate way, it surely can’t be a coincidence… can it? The house on which it is carved – 61 Hague Street – also has a datestone of 1773, which provides us with a nice terminus post quem (the opposite of a terminus ante quem – a date after which it must have happened) – it can’t have been carved before 1773 as the building didn’t exist.

Nope, it’s all a bit strange, but I love a mystery.

And finally… yup, you guessed it. Drum roll please…

SOME POTTERY… BUT NOT LOTS!

A single sherd found between the setts of Bank Lane, Tintwistle, right by Bottoms Reservoir.

Nothing too interesting. I mean it’s a nice sherd of Transfer Printed Ware – probably a bowl, as it has flowers printed on the interior and the exterior.

It is also unlikely to have been dropped in the last 100 years or so, and has thus laid there, between the cracks, just waiting for a dashing young(ish) and handsomely moustachioed archaeologist to find it. I was going to make this a full on pottery post, but it’s already too long, so the pottery will have to be next week, or so. I know, I know, but good things come to those who wait. And whoever is crying and yelling “no, no, dear lord please not next time” – you must try and control your excitement.

A TINTWISTLIAN TRACKWAY

However, back on track, and it’s Bank Lane that proves the focus, the sherd was just a way of getting onto the subject! This is a really interesting trackway, and is one of the two original (probably medieval) ways into Tintwistle from Hadfield, and before the Woodhead Pass bisected it (this stretch was made and improved in 1844 – look at that, another terminus ante quem!), it would have linked up with Bank Brow to get to the heart of the village. Incidentally, the other trackway goes via Lambgates, Roughfield, under the reservoir, and enters at the east of Tintwistle).

So, Bank Lane then. It curves up, and just before it reaches the Woodhead Road, it runs below the retaining wall of Christ Church, Tintwistle.

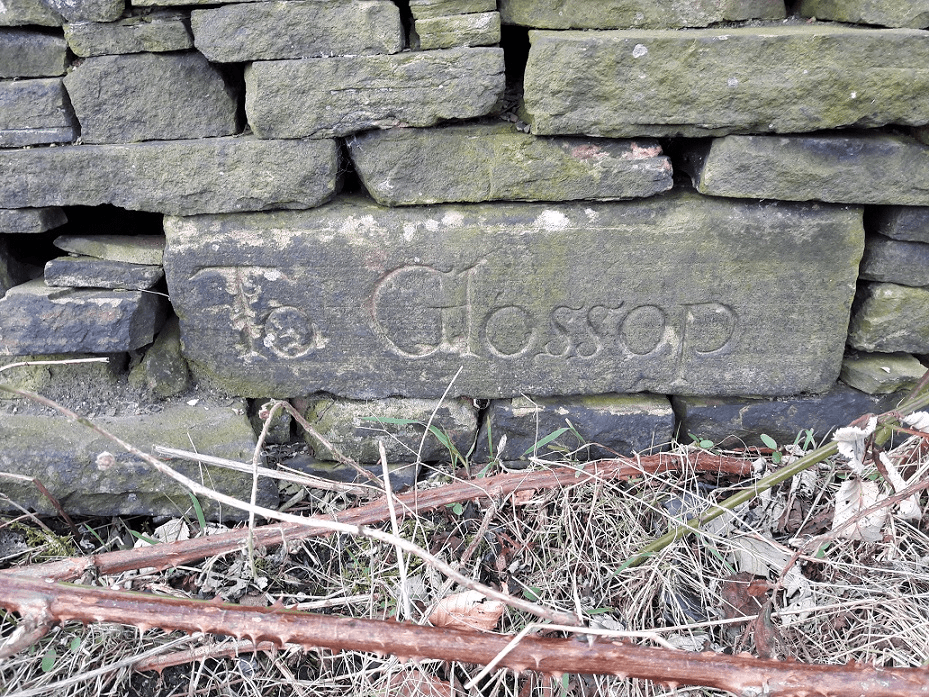

As I said above, I do love a nice old wall, and I’m always aware that there might be interesting details hidden in them… and so it proved to be the case here. Firstly, I spotted this date:

I think it reads 1841. Now Christ Church was built in 1837, is it possible that the wall was put in place 4 years later, perhaps replacing an older one? On balance, I think yes, but a quick rummage through the church records might reveal some detail.

And then I noticed this:

I am fairly certain that this is a set of initials, carved messily but cursively into the stone. I have made an attempt to outline what I think they are, but honestly it is entirely possible that I am just seeing things. I’ll let you, dear and gentle reader, decide for yourselves.

Possibly it reads ‘J. B’. Possibly?

And finally, another carved cross. This one looks more modern, and perhaps is a mark for where some utility is under the road? Not sure.

Anyway, Bank Lane deserves a closer look. I have a whole ongoing project that is looking at these ‘original’ trackways that linked all the farmsteads in the area, as many are still preserved. It’s way more than a single blog post, but I’d like to do a series – examining each trackway, photographing it, marking it on the map, and recording any finds. Oooooh, that sounds exciting, I know.

Finally…

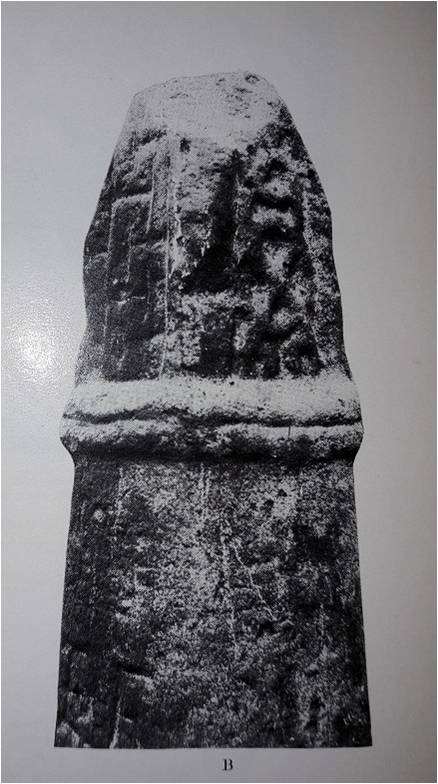

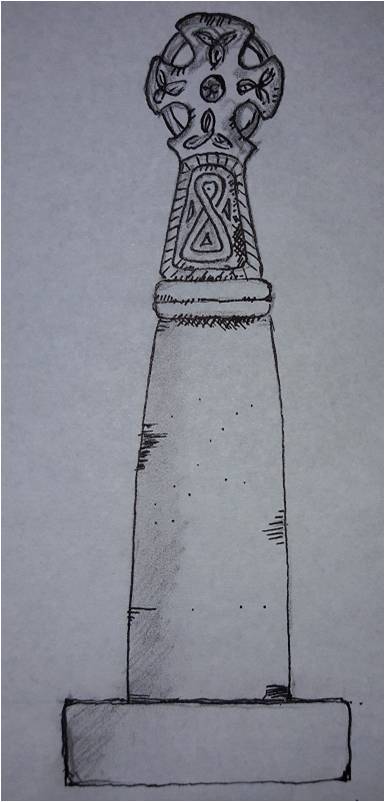

WHITFIELD GUIDE STOOP

I have blogged about the guide stoop several times before, as it’s a vital part of the history of the area, and presents something of a mystery – please read here and here for the full lowdown.

At the start of lockdown, I went on a walk past the guidestoop, and was horrified. Someone had had some work done in their back garden which required the rebuilding of the back wall and the removal of a large amount of soil. Whoever was doing this work had spread the soil along the track, at the bottom of the wall, and had completely buried the guide stoop in 2ft of earth. I mean, benefit of the doubt, they might not have noticed it. Here’s what it looks like currently:

If they did see it, however, then they were morons, and I just hope they kept the guide stoop in position, and didn’t steal it. Now, I haven’t re-excavated it yet for two reasons. Firstly, it’s a lot of earth, and a lot of brambles! And secondly, I’m not entirely certain where the guide stoop actually is under all that! all my photographs are of it in closeup, rather than a long view that gives a location in relation to the upper part of the wall. So, I have a favour to ask. Well, two actually. Firstly, does anyone have a long view that shows the top of the wall and the guide stone they could let me see? And secondly, does anyone fancy meeting up with a shovel, so we can dig the thing out and once again have back it on display? It shouldn’t be too much of a job. Anyway, drop me a line if you fancy volunteering.

Right, after that mammoth post, I’m going for a lie down! I will post the pottery in the next week or so – it’s largely written, and the photographs are ready to go, so it won’t take long… I can feel the wave of excitement from here.

Until then, look after yourselves, and each other. And I remain,

Your humble servant,

TCG