What ho, you wonderful people, you.

So, despite having half a dozen half-written posts, piles of interesting objects and sherds to talk about, and a few adventures to recount, I want to try something a little different today. “Oh no!” I hear you cry. But fret ye not, gentle reader, for it is still archaeology, it is still Glossop based, and it is still interesting. But it is a little… quirky. You’ll see what I mean.

I have a friend who is a writer, and quite a good one at that. He has often mentioned that stories usually start with what he terms a “What If?” moment, where something – often an object – presents itself, and the question is posed “what if…?” From there the story grows, based on and around that one question. The answer that comes doesn’t have to be ‘real’, it is fiction after all, but it has to be possible. What if a house was haunted? And what if the house fell down? And what if a brick from the house was haunted too? And what if a dashing archaeologist took the brick home to write about it on his extremely popular and incredibly interesting blog? What if…?

Archaeology, I think, uses a similar technique. An object is excavated, and the interpretation – the story – begins. However, where we differ from writers is that we base our ‘what ifs…?’ on evidence and supposition grounded in data. The interpretation, in this sense, has to be ‘real‘, although it is only ‘real’ for as long as the data supports it. Sometimes though, It’s fun to play “what if…?” – and here we join today’s post.

Stone heads. A lot has been written about them. They are cursed and evil. Or they are warm and friendly. They are ‘Celtic’ (i.e. Iron Age or Romano-British) in date. Or they are medieval or early modern in date. Or a combination of both. They represent an unbroken pre-Christian tradition, and an aspect of the whispered ‘Old Ways‘. Or they are simply folk art, and just decorative. Or they are magically protective (that wonderful word, apotropaic, again). Or both. Or neither. A brief trawl of the internet gives a lot of different sites and opinions, ranging from the scholarly and the more open minded, to what can only be termed outright nonsense.

Whatever they are, carved stone heads are a feature of this part of the Pennines – from Longdendale, over the hills to West Yorkshire, and up to the Calder Valley. I actually have a serious project that is looking at them; cataloguing known examples from Glossop and Longdendale, and trying to place them geographically, as well as giving some sort of date to them. There are at least 23 examples from the Glossop area, with more doubtless waiting to be uncovered. But it’s an ongoing project, and not really ready to publish – here, or anywhere else for that matter – and I just keep chipping away at it. It was during the course of trying to map where they were found, that I noticed something very interesting.

Before we go any further, I should state that my personal belief is that most of the stone heads are medieval or post-medieval in date (indeed, there is a record of them being carved in the 19th Century). That’s not to say that Iron Age ‘Celtic’ examples don’t exist (one was found at Binchester Roman Fort, in County Durham in 2013), it’s just that it is very difficult to date them as they usually don’t come from any secure archaeological context, and basing a date on ‘style’ or method of carving, as has happened in the past, is notoriously dodgy. That stated, there is the possibility that I might be wrong. And this led to my ‘what if…?‘ moment.

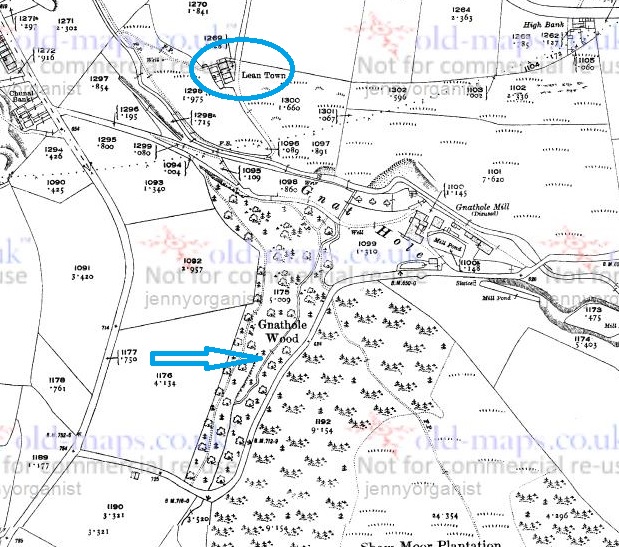

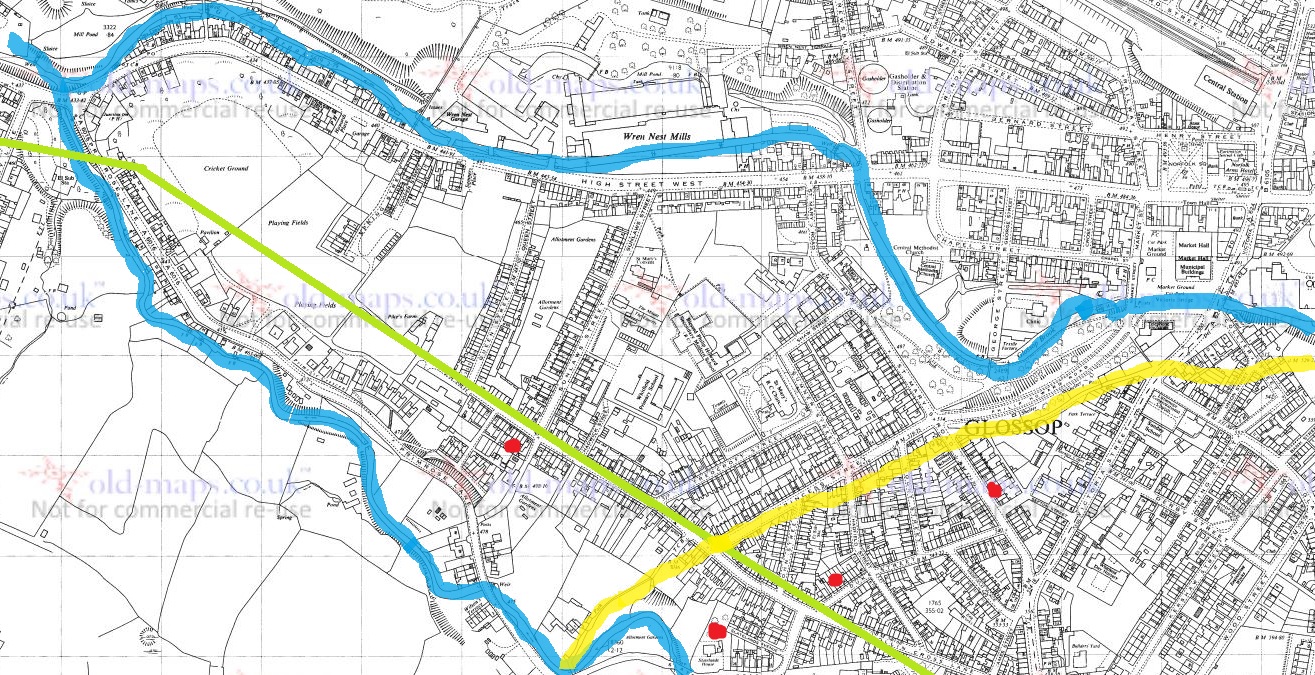

Back to the find location, sadly the majority of the heads are simply “found in Glossop area“, and thus have no exact place. But from various sources, I was able to identify where some of the heads were found. The distribution map is below:

They seem to be dotted all around the area: Mouselow, Manor Park Road, several in Old Glossop, etc. However, looking at the above map, I noticed there was a distinct grouping in Whitfield – four of them centred around Slatelands Road and Hollin Cross Lane. Hmmmmm… let’s have a closer look, then.

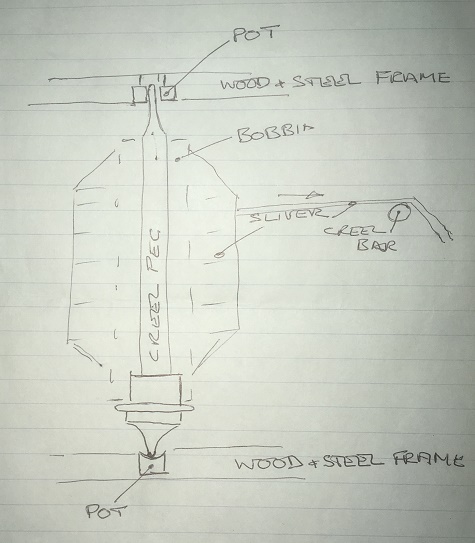

Duke Street, Pikes Lane, St Mary’s Road, and Slatelands Road. Geographically, they are in the same tangle of roads in that area. But the heads more than likely pre-date the Victorian roads, so we need to strip them back. What was there then? Well fields, mainly, though the medieval track from Simmondley to Glossop ran through here (that blog post is coming, I promise!). And before that, the Roman road also ran through here, along Pikes Lane, before kinking over Long Clough Brook and onto the fort and settlement at Melandra.

And then, the “what if…?” hit me.

For the sake of a good story, what if these heads actually were Iron Age or Roman in date? What could this cluster mean?

Looking again at the area stripped of the Victorian houses, it’s very clearly a promontory, a high plateau that runs between two brooks – Glossop Brook to the north, and Long Clough Brook to the south. In the Iron Age, they liked their elevated places – Mouselow, which dominates the area, is a classic Iron Age hillfort, and others exist nearby, at Mellor and Mam Tor. One only has to look at St Mary’s Road from Harehills Park to see how steep those slopes are (try doing it pushing Master Hamnett in a pram with a load of shopping from Aldi). And on the other side, who hasn’t cursed Slatelands Road halfway up, gasping for breath. This is a very real landscape feature, completely masked by later development, but one which would have been very visible back then. This would have been particularly true where the peninsular narrows at the west, leading down to the junction of the two brooks. This too, is significant.

Throughout prehistory water was a sacred thing, and was considered ritually important. A spit of land, elevated, defined by water and ending in the confluence of two bodies of water, would have been hugely significant. Actually, a perfect place for an Iron Age temple or shrine, perhaps one devoted to the ‘Celtic head cult’ as suggested by scholars such as Dr Ann Ross (in her Pagan Celtic Britain)? Indeed, the North Derbyshire Archaeological Survey notes that the number of heads in the Glossop area “might suggest a cult centre” based in the town in the Romano-British period (Hart 1984:105). It has been suggested that the heads are sometimes associated with liminality and boundaries, and were protective. What if they were they placed facing down the peninsular, to mark out the sacred space, and to defend it?

The Roman road moves through this promontory, sticking to the high ground away from the valley floors and marshy terrain, as the Romans preferred (see map below). But what if the location of the possible shrine or temple influenced the choice of road location, ploughing through the sacred enclosure, perhaps to make a point about Roman dominance?

What if…?

Now, I’m not suggesting for a moment that that the above is absolutely true; this is a wild flight of fantasy, and pure fiction – a story. Indeed, doubts are being raised about the reality of the ‘Celtic head cult’ theory in general. But it is a possibility, at least: an archaeological what if…? However, if that isn’t the answer, there still remains the issue of why four stone heads were found in a cluster in this area. What is going on?

If we return to my original thought, that the heads are medieval or post-medieval in date, might they be related to the Simmondley – (Old) Glossop trackway in someway? If we look at the map above, we can see this track (marked in yellow) runs broadly along the line of Princess Street. And just to the east of the three of the heads run along the same alignment. Is this significant? What if people somehow, and for some reason, deposited these heads to the east of the track? But why? Well, I came across a possible reference to just such a practice in this area – Clarke states that “Oral tradition in the High Peak of Derbyshire suggests heads were buried as charms beneath newly-built roads, presumably to keep permanent watch over them” (1999:286). He cites no sources for this “oral tradition”, but this type of apotropaic function – preventing witchcraft and promoting good fortune – is associated with carved heads all over the United Kingdom (Billingsley 2016). Perhaps, then, we are seeing the ritual deposition of carved heads as part of the road building tradition.

What if…?

No, it is a mystery, and ultimately we are left with questions for which there are no obvious answers. Three of the heads are in Manchester Museum, and the fourth presumably in the hands of the owner/finder. I will have to go and see them, as that might help in dating. As I say the project is ongoing, and any comments or help in the area would be greatly appreciated. Do you know of any stone heads? Do you have photographs of any? Or stories – they seem to attract folklore and superstition like nothing else! Please contact me in the usual way – email me, or through twitter ( @roberthamnett ). Or just come and find me in the street, as people are increasingly doing… so much for pseudonyms and anonymity!

I do hope you enjoyed the little flight of fantasy, but we’ll be back to business as usual next time – the sherds are mounting up! Until then, look after yourselves and each other.

And I remain, your humble servant

RH

References:

John Billingsley – Instances and Contexts of the Head Motif in Britain

David Clarke – The Head Cult: Tradition and Folklore Surrounding the Symbol of the Severed Human Head in the British Isles. (Unpublished PhD Thesis, accessed here)

Anne Ross – Pagan Celtic Britain: Studies in Iconography and Tradition