*well, one, actually… but it is rather an interesting one. And also, my apologies to The Beatles.

What ho! good folk of the blog reading sort, what ho!

Now, as you probably know (for the Bard says it so) some are born with pottery, some achieve pottery, and others have pottery thrust upon them… or something. I think I fall squarely into the latter camp, if by thrust you mean stumble across it, even if one isn’t looking for it.

And so it was the other day. I had dropped off young Master CG at a friend’s birthday party, and had taken the opportunity to saunter into town to pick up a few things (certainly nothing pottery related: lego, wine, and masking tape, I think it was… which gives yet another somewhat intimate peek into my life). I wandered down High Street, and wondered if it was too early for a glass of something cold and refreshing. Crossing the end of Market Street I looked left and idly noted that the road was closed… and then I noticed the ground had been dug up, with a good sized pile of spoil indicating that there was a hole.

Now, as an absolute rule, if an archaeologist sees a hole in the ground, they will peer into it. It’s so natural, so predictable, that it has become a sort of archaeological equivalent to the Masonic Handshake, and using it you can spot us a mile away. “I say! What’s that chap over there doing – peering into a hole?” they say. And comes the response “Oh that’s just old TCG, doing a spot of ‘hole peering’… he’s one of those archaeological types, don’t you know – curious fellows“. This is also why you never see large groups of archaeologists walking together; if they accidentally stumbled across some roadworks they could be there for hours, peering. From the outside it would look like a mass escape from some sort of specialised care home, the inmates muttering and stroking their beards, pointing at things that might, or might not, be there. And peering. People would get frightened, angry mobs would form, torches would be lit and pitchforks procured, the police would get involved… No, it’s safer we travel in ones and twos.

But I digress from the story.

“Hmmm“, I muttered, and my thought process went something like this:

“Oooh, a hole… I must have a peer.”

Are those setts? Nice!

Wait, look in the soil… is there any pottery?

And so I did the only sane and rational thing I could do… I wandered over and did a spot of peering! And my word, what wonders were therein contained… chock full of goodies, it was. And yes, I realise that ‘goodies’ as used here is an entirely subjective word!

Let’s start with the Brown Salt-Glazed Stonewares:

At the top left, we have a bowl or cooking pot with a rolled rim and a pot belly with a rim diameter of c.14cm; if it wasn’t Stoneware, I’d be thinking that it was Roman! Next to that part of the base to a large cooking pot; you can see the wear on the base where it was put in and out of an oven many times over the years. Bottom left is a thin walled open vessel, and with a diameter of 10cm is probably a mug with a horizontal linear banded decoration. The shiny lead-based glaze is particularly noticeable here, as is the orange peel effect on the exterior, characteristic of a salt glaze. This is also clearly visible in this sherd (it took me a while to get the light right on this shot, so you’d better appreciate it!).

The sherd on the right is probably from a jar or similar cylindrical shape. That on the left is the base of a cooking pot of some form. The foot is 8cm in diameter, but it is pot-bellied, so is actually quite large. It’s also quite coarsely made, being thrown quickly on the wheel, and looking at the base you can see detritus from previously made vessels, and which have been fired onto this pot. You can also see the wear on the edges of the base where it was pushed in and out of a metal oven. Interestingly, you can also just about make out the circular marks made by the wire cutting the wet clay bowl from the potter’s wheel – a snapshot of the manufacturing process.

Then we have some Industrial Slipwares:

A selection of open vessels. Rims from two lovely bowls, both of 16cm in diameter, and probably from food bowl – soup or stew, perhaps. The one on the left has a striking spotted design, and on the right, a variegated type with a joggled earthworm decoration (see the Rough Guide to Pottery Part 3 for more on this). To the right we see some more sherds, these are probably from tankards (for example, the one top right with the dark brown band has a diameter of c.12cm, which is about right).

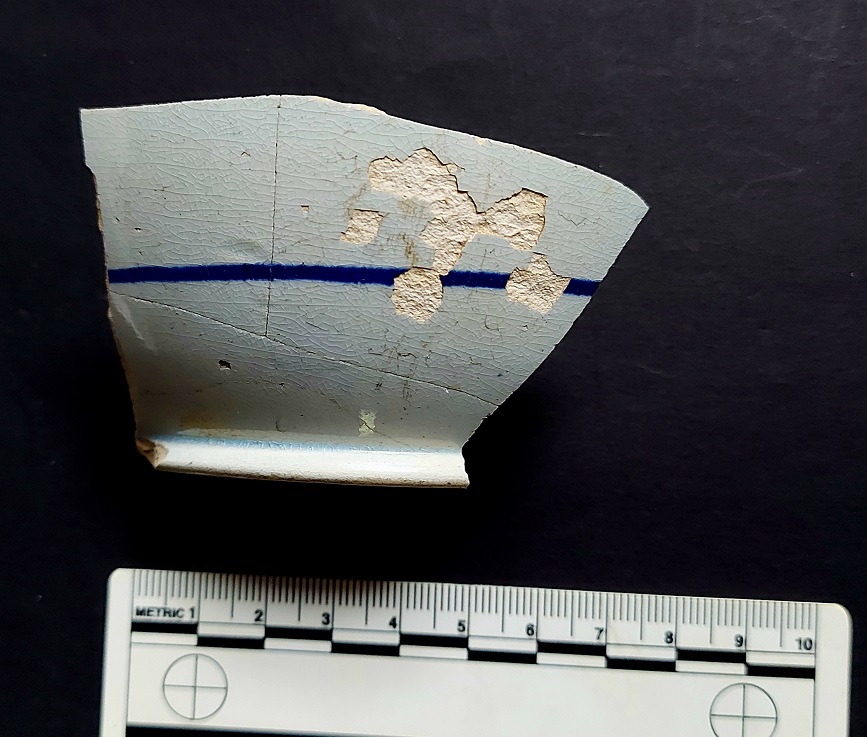

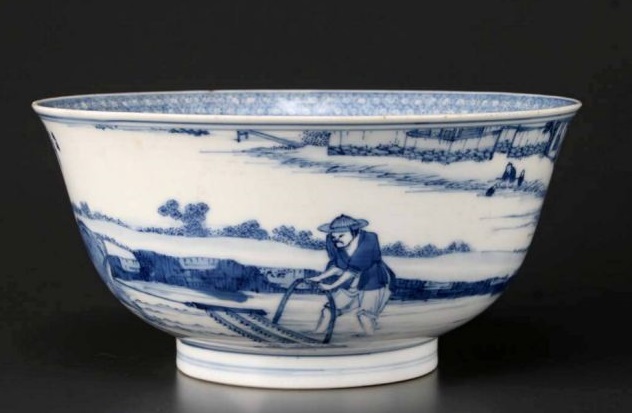

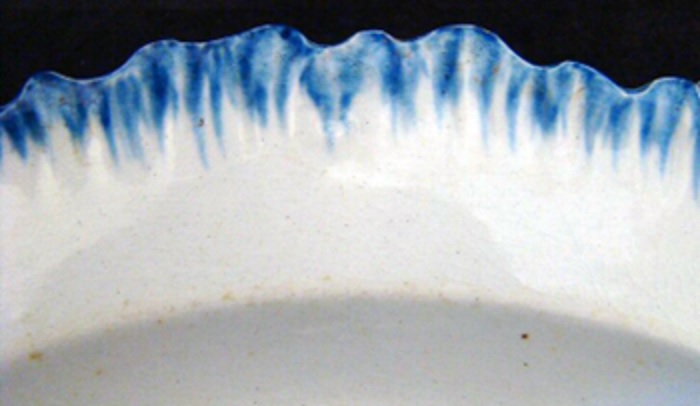

Blue and White Transfer Printed:

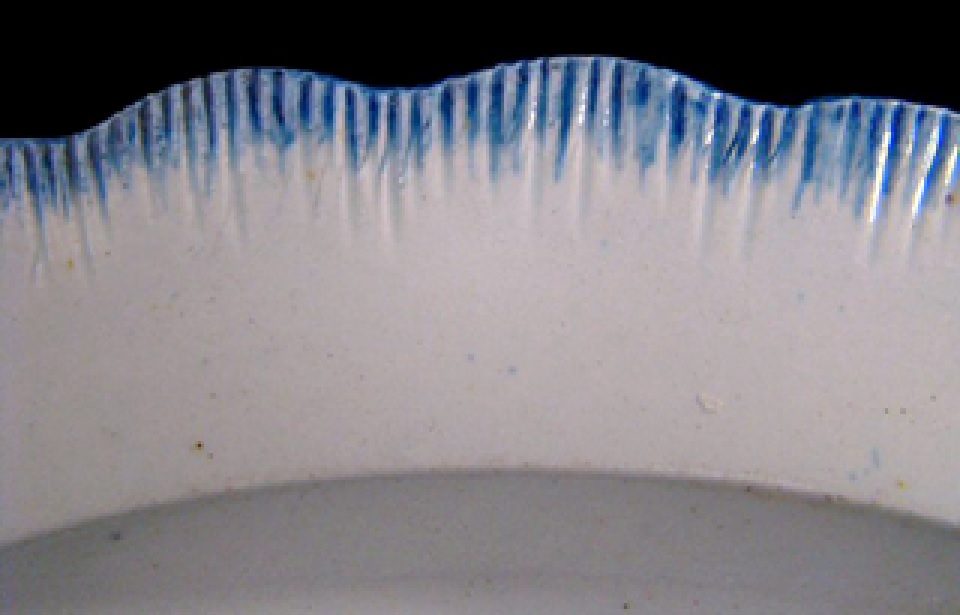

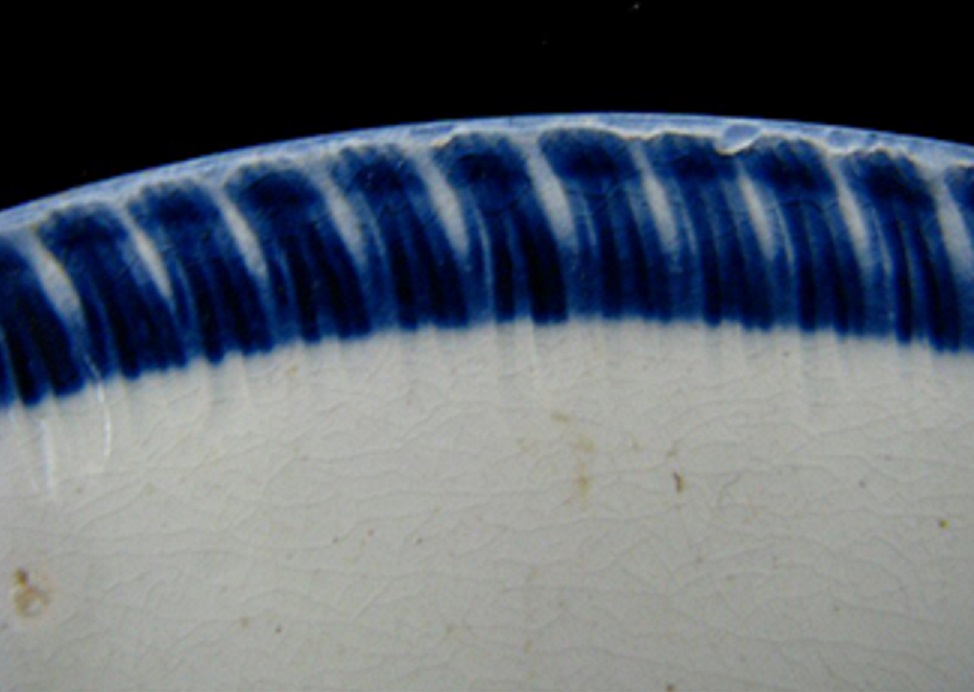

Surprisingly, there wasn’t much Blue and White Transfer Printed material here, but I only collected from the surface, with no digging (which makes me wonder what I missed… eek!). What there is is fairly standard, a few bits of Willow Pattern, including a small plate or saucer of c.16cm diameter, and other assorted bits. There is also a moulded rim from a Shell Edged plate or shallow bowl.

Some hand-painted Victorian sherds:

Hand-painted pottery was quite popular, and can be quite attractive in an abstract way – the painting being done very quickly produces some wonderful designs. I have a feeling both of these come from larger jugs, or possibly vases, although the one on the right reminds me of some of the hand-painted designs you get on Spongeware vessels (see here). This stuff is the subject of a future Rough Guide, although there really isn’t much more to say than colourful designs on a refined white clay and glazed.

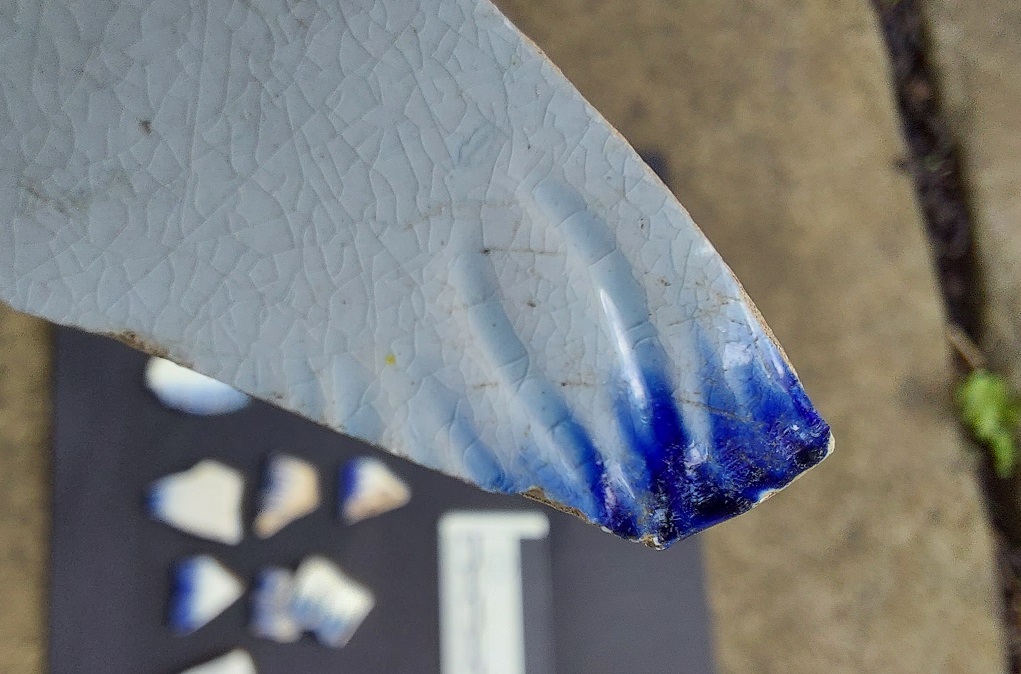

Here we have some Black Glazed sherds.

This stuff is interesting, and is going to get its own entry in the Rough Guide, too – perhaps next time (can anyone else hear screaming?) – so I’m not going to go into too much detail here. However, I will say these sherds come mainly from large thick-walled vessels, and specifically pancheons – huge deep bowls traditionally used for separating cream or proving bread. They are very coarsely slipped and glazed usually on the inside only, and typically have grooves on the interior, made by fingers during the shaping process. As I was peering I pulled out a sherd which has since proved to be my favourite ever example of this type – look at this beauty!

A rim sherd of a large pancheon measuring roughly 56cm in diameter – a monster! It has a lovely black glazed interior, with great drips running where it was splashed and placed upside down to empty and dry before firing. The exterior is something to behold, too:

Wonderful grooves running horizontally around the body, made with a comb of some sort and which left some of the flashing. And look at that handle! For some reason it rare to find handles (there’s usually two of them), but this one is perfect – you can even see the potter’s thumb mark where he has pressed it onto the body of the vessel.

And look at the profile, held up at the correct angle to allow us to see how steep the vessel would have been, and showing the thick heavy rim.

I love how monstrous this thing is… it’s truly fantastic! I’ll be waxing lyrical about this pot some more when we get to the Rough Guide.

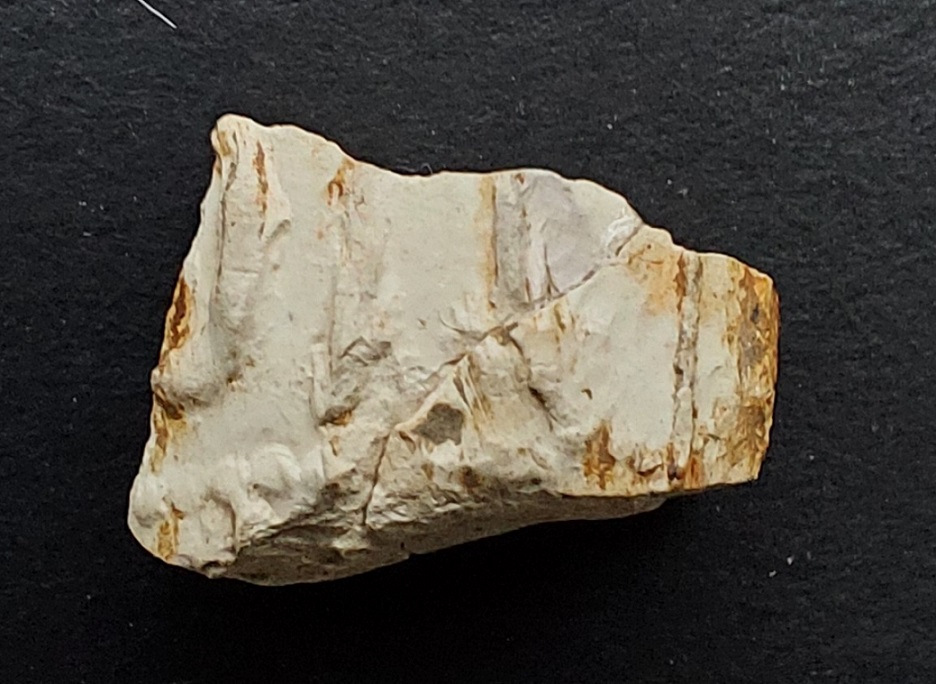

And finally, this last one is a mystery sherd, by which I mean I don’t know what it is, exactly.

It’s shaped in a way that suggests it was a statuette, rather than a cup or bowl, and if I was a betting man (which I’m not), I’d say it was one of those pottery dogs the Victorians loved so much. Or did they? And here I’m going to share with you a passage from one of my all-time favourite books – Three Men in a Boat by Jerome K. Jerome:

“That china dog that ornaments the bedroom of my furnished lodgings. It is a white dog. Its eyes blue. Its nose is a delicate red, with spots. Its head is painfully erect, its expression is amiability carried to the verge of imbecility. I do not admire it myself. Considered as a work of art, I may say it irritates me. Thoughtless friends jeer at it, and even my landlady herself has no admiration for it, and excuses its presence by the circumstance that her aunt gave it to her.

But in 200 years’ time it is more than probable that that dog will be dug up from somewhere or other, minus its legs, and with its tail broken, and will be sold for old china, and put in a glass cabinet. And people will pass it round, and admire it. They will be struck by the wonderful depth of the colour on the nose, and speculate as to how beautiful the bit of the tail that is lost no doubt was.”

I suspect that this is a fragment of that tail!

Finally, we have a fragment of a clay pipe bowl and a piece of stem.

Neither is particularly interesting as such, and I sometimes refer to clay pipes as the cigarette butt of the Victorian period – they were mass produced, smoked and thrown away – but they are always a joy to find. The slightly tatty looking organic object on the left of the photo is the remains of an oyster shell. These are quite a common find from the Victorian period, though perhaps less common away from the coast for obvious reasons. In fact, oysters were an important food source for many, sold pickled in vinegar and spices, or made into pie, and certainly by the time of the railways, they could be moved around the country in huge quantities to feed the hungry lower classes cheaply.

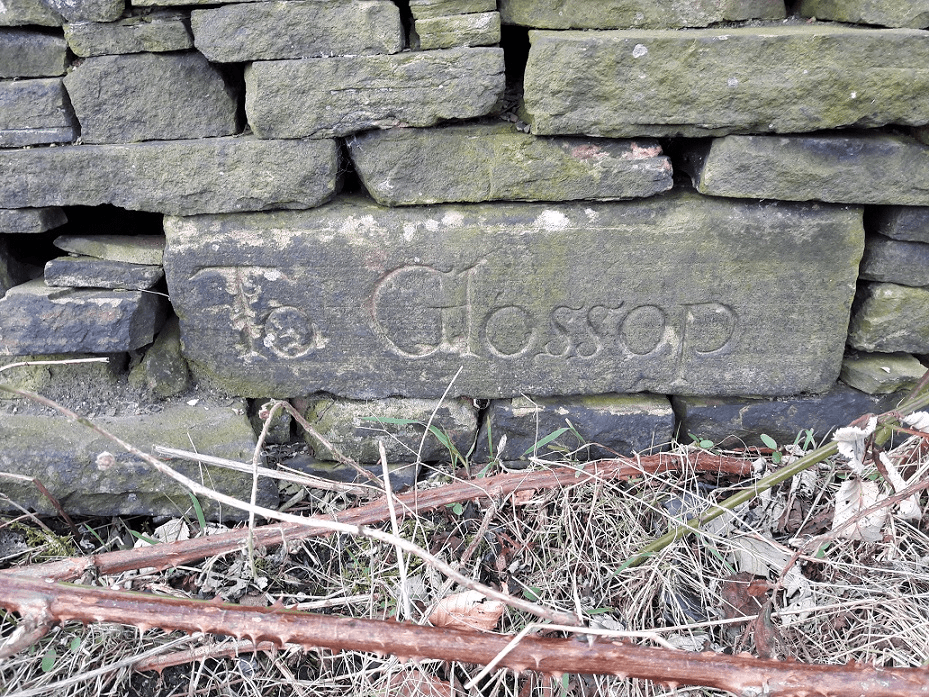

In terms of dating, the construction of the market hall and grounds, and subsequently Market Street, provides us with a lovely and quite solid Terminus Ante Quem – the latest point at which an event could have happened. Put simply, the pottery came from soil underneath the road surface of setts laid down when the road was put in – 1844 or thereabouts. It couldn’t have been deposited any later than that (the road surface prevents it) therefore all the pottery must date to 1844 or earlier. And from a sherd nerd’s perspective, I would agree with the archaeological method; there is nothing here that needs to be later that 1840. You can see the original sett covered road surface in this photo, with a few setts still in-situ. You can also make out the buried surface and the natural soil underneath.

To make it a bit clearer, let’s look at it side on – in section.

If you look at the photo above, you can make out the tarmac layer on top of the stone setts left in-situ – this was what you drove on the last time you drove down Market Street, laid down probably in the 1960’s, and many times since. The stone setts are the original Victorian road surface. Below these, in a reddish brown in the diagram above, is the disturbed original ground surface, and it is from this that the pottery was taken. Below that (only not as clear cut and obvious in the photo) is the original undisturbed natural clayey soil laid down during the last ice age or so.

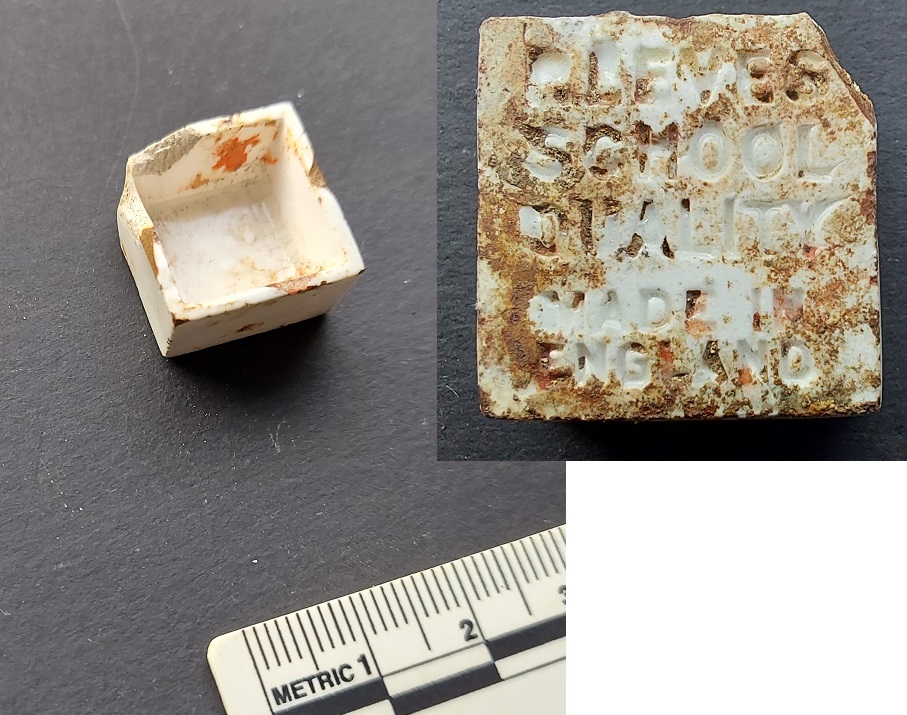

The origin of this material, and why it ended up there, cannot be proven, but we might hazard a guess. From 1838 onwards, the town hall was constructed, designed from the outset to incorporate shops and businesses into the complex. One of these was a pub – The Market Vaults – that stood on the corner of (what was to become) Market Street and High Street West (it later became The Newmarket, and is currently Boots Opticians).

Well, technically, this front part was a grocery store, it was the back, facing into the market place that was the pub. And it was right next to this building that our hole was dug. It’s not in the realms of fantasy that broken pottery and rubbish would be thrown out of the back door of the pub onto the muddy wasteland – the area would have been a building site between roughly 1838 and 1844.

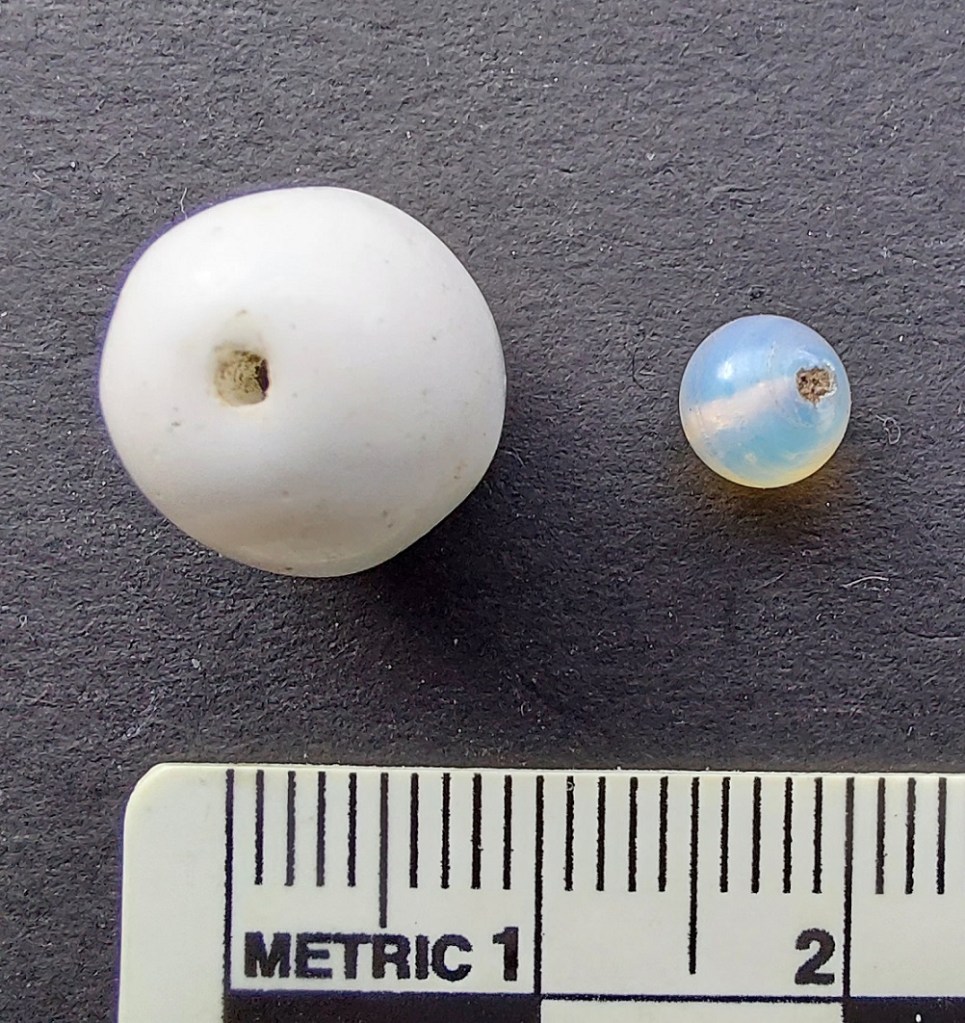

There are three things that reinforce this theory. Firstly, the pottery contains a large proportion of Industrial Slipware, a ware type particularly associated with pubs. Secondly, the oyster shell is a classic bar snack of the Victorian and earlier periods, cheap and cheerful (then, at least – now they are, well, bloody expensive and, quite frankly, inedible). Lastly, the condition of the pottery; it all has sharp edges and clean breaks, which tells me that it has not spent any time kicking around the soil, being trodden on, or moved around at all: it was simply dumped and never touched again until being paved over. And although in ‘History in a Pint Pot‘ (the history of Glossop’s pubs), David Field notes that the first mention of a pub here is in a newspaper of 1865, I think it highly likely that the grocery was open all year, and that the enterprising owner – Mr Edward Sykes – would sell beer round the back on market days.

Fast forward 180 years, and some dashing heroic archaeological type wanders over to a hole, has a peer and, well, here we all are. And here, we must turn once again to Three Men in a Boat. Later in the same page as above, J notes:

“The blue-and-white mugs of the present-day roadside inn will be hunted up, all cracked and chipped, and sold for their weight in gold, and rich people will use them for claret cups.“

If only he knew! And if only I could find one complete enough from which to drink claret!

So remember, always have a look into a hole… you honestly never know what you might find. But be quick and be bold, as before you know it all is returned to normal and the opportunity to explore a little of the past is gone…

EDIT

I have just come across this rather wonderful article, written by the truly amazing Graham Hadfield, about the history of Market Street. The whole of Graham’s website – GJH.me.uk – is an absolute mine of Glossop history, and he really puts in the effort to investigate the history of the place. I don’t bang on enough about the other people who are unravelling the history of here, as I’m not the only one, but let me recommend this site.

Incidentally, as I was peering I heard shouting behind me, and bounding into view came my lovely neighbours (hello H & S!). Apparently, their conversation prior to this had gone along the lines of “look at that weirdo poking around that hole, what’s he doing? Oh, hang on… that’s TCG!”. It’s nice to be known… I think.

Righty-ho, I think that’s the lot for today. I’ve got places to go and things to do (mainly housework, to be honest, but there you go, such is the life of the dashing explorer). In all the recent rain, it is well worth keeping an eye on the ground to see what the pottery fairy has sprinkled about – let me know if it is anything good. Also, big news is coming… I think, but until then, look after yourselves and each other. And I remain.

Your humble servant,

TCG