A brief one today. Taking advantage of the lull in the rain coupled with a bit of a breeze, Master Hamnett and I went to fly a kite in the fields off Hague Street. On the way back, I found some bits of pottery which spurred me into doing the blog post that I have been thinking of doing for some time.

Whitfield Avenue runs downhill in a broadly NW – SE bearing from Hague Street to meet with Charlestown Road, and is parallel to Whitfield Cross.

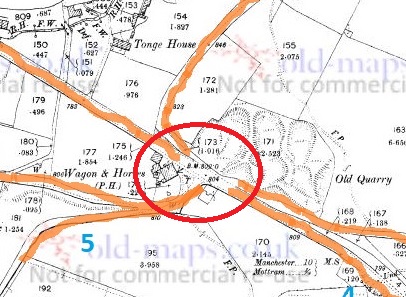

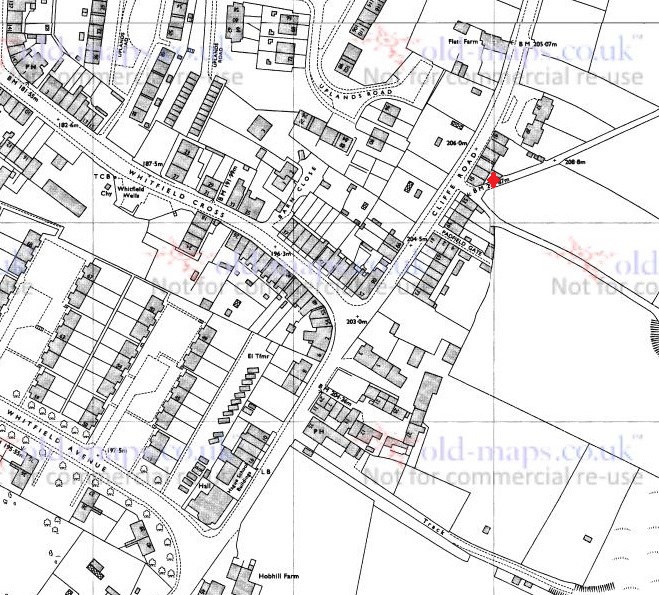

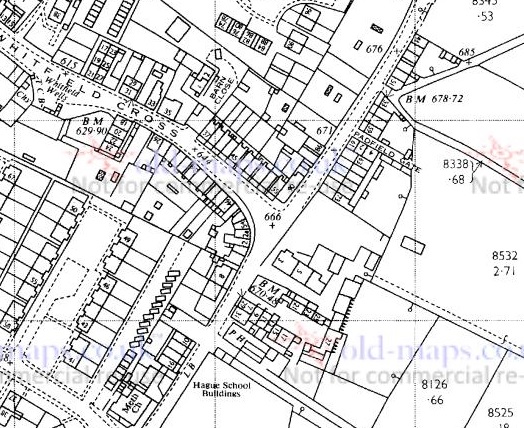

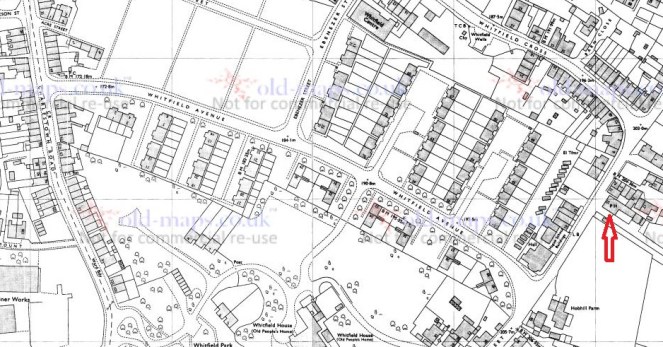

At first glance, it is not a particularly interesting road. The product of the 1960’s demolition and rebuild of the Whitfield area, the road didn’t exist prior to this, as you can see from the map below.

What is there is a footpath, walled for most of its length, along the long thin fields that characterise the fields of Whitfield – possibly a survival of the medieval ‘croft and toft‘ field system, or more likely a result of the enclosure of the land there in the early 19th Century. This is interesting, as we shall see, but it also probably explains why the council chose there as the location of the road – using an already existing path.

Historically, then, it is interesting, but not exactly earth-shattering. That is, until you peel back the modern, and take a closer look.

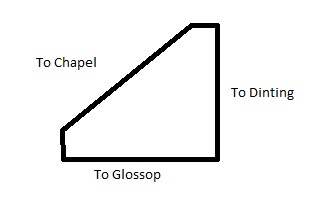

Hague Street was the original packhorse road from Chapel en le Frith to Glossop (now, Old Glossop) – there is some discussion about the road, here, and there is the Glossop Guide Stoop, too (and more here). It was an important route, and the village of Whitfield grew around it – this is the oldest part of the area. Dating for this road is tricky – we know it was there in the 10th Century, as the Whitfield Cross was placed at the junction of Hague Street and Whitfield Cross (the road), and presumably some form of settlement – perhaps just a farmhouse – was there at the time. Beyond this, however, we have no evidence. However…

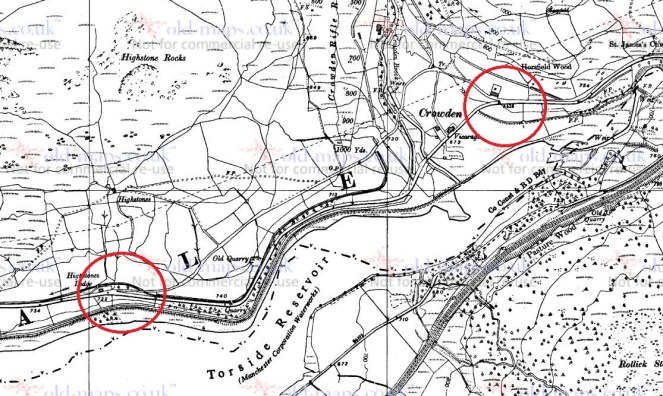

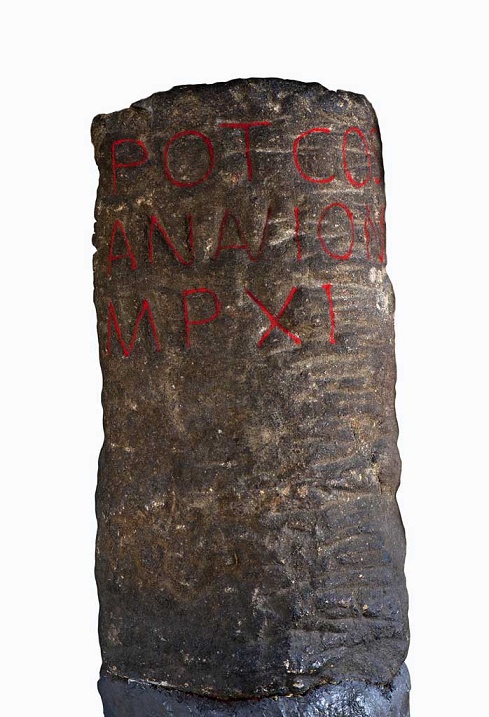

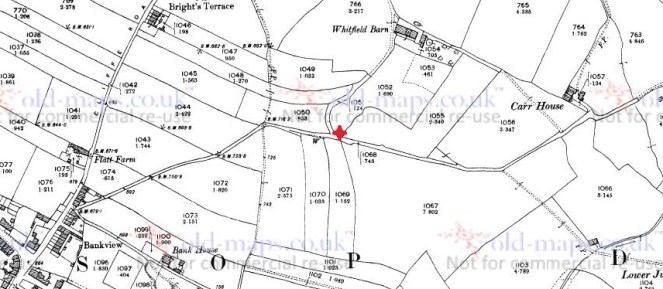

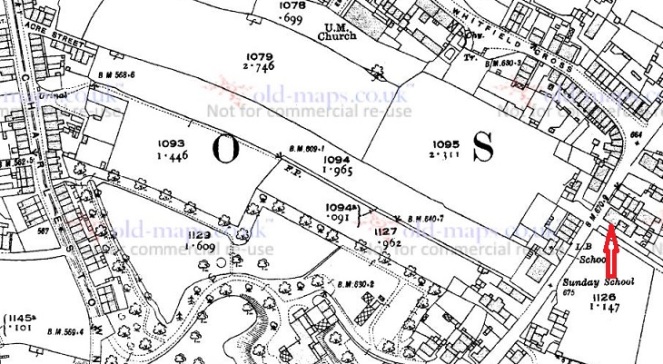

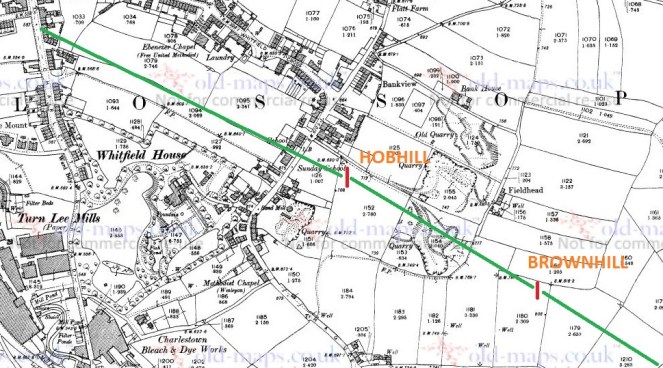

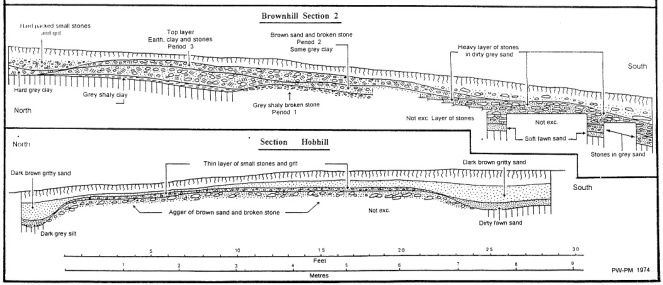

In the early 1970’s a series of excavations were carried out by two archaeologists – Peter Wroe and Peter Mellor – in order to establish the line of the Roman roads to and from Melandra Fort. Although this thorny and difficult subject has been much debated (and only recently – possibly – put to rest), they made great leaps. One of the roads, that coming from Navio Fort (Brough, near Castleton) passes through Brownhill, and comes through Hob Hill Meadows, and continues down the line of what is now Whitfield Avenue. From there it travels down the road that are now known as Hollincross Lane and Pikes Lane, and over into the fort.

Yes, you read that correctly, Hollincross Lane/Pikes Lane, especially its latter part toward Pikes Farm, is a Roman road.

The excavations not only revealed the broad line of the road, but also how the road was built. The next picture shows what is called an archaeological section drawing – essentially a slice of the road was taken out, and the side of the slice was drawn showing the layers that made up the road. And all this is just 1ft below the ground, which is quite remarkable.

Interestingly, and as an aside, Hob Hill as a placename means ‘Devil’s Hill’ – I have said it before, I love it when folklore and history meet.

The ‘original’ footpath on the first map pretty much follows the line of the Roman Road. This is interesting, and suggests that the path used the surface of the Roman road, or a later incarnation of it; there is no point in making a new path if you can use an existing one, especially if that one has a good surface. What I like about this is that a road built 2000 years ago, directly dictated to the council the course of a road built in the 1960’s. History affects us in the present in many ways.

At the top of the road stands this wonderful, forlorn, and if I’m a little honest, slightly terrifying, building – the former Chapel/Sunday School.

I have always been intrigued by this building, and so taking advantage of the open gate, I had a look around.

It’s really quite a lovely, if very Victorian, building, full of nice touches.

There is also a datestone, helpfully recording the dates of the original construction, the rebuild, and what its function was.

Actually, it was also altered a third time in 1931 to incorporate the chapel further up Hague Street which by then had fallen into disuse. This Methodist chapel (itself rebuilt from the original 1813 version), had once contained the pulpit from which John Wesley had preached, and which in 2010 was returned to its rightful home in New Mills (see here for information and photograph).

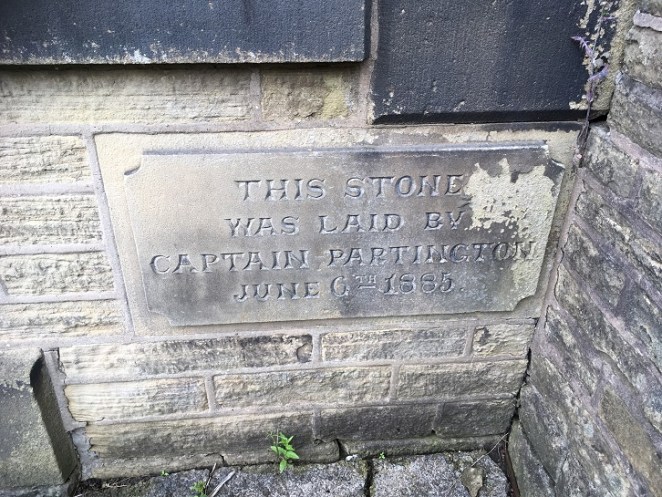

The 1885 rebuild had four cornerstones embedded into it, recording the local worthies who attended the ceremony, and which allow us a peek into Late Victorian Glossop life. Here they are:

So these are the stones, but who are these people?

Captain Edward Partington: Partington was a very important person in Glossop’s Victorian history – his biography is impressive, but in summary he was born in 1836, and moved to Glossop in 1873, buying up all sorts of mill concerns, and ending up Rt. Hon. Edward Baron DoverdaleRt. Hon. Edward Baron Doverdale, dying in 1925. He did a huge amount of philanthropic work around the town (funding the library, for example), and served as Captain in the 3rd Derbyshire (Volunteers) Rifle Corps. Oh, and was a mean rugby player, by all accounts.

Alfred Leech: There is very little information about Mr Leech that I can find. He crops up in a number of interesting places associated with Glossop society, and he is mentioned in the London Gazette as being elected as a land tax commissioner. His address is given as Cowbrook Cottage, Sheffield Road, Glossop. More research is clearly needed!

John Sellars: He is even harder to pin down. He might be the Methodist lay preacher mentioned in “Echoes in Glossop Dale: The Rise and Spread of Methodism in the Glossop Circuit” by Samuel Taylor of Tintwistle (1873). Or then again, he might not.

W. S. Rhodes: William Shepley Rhodes was a councillor, alderman and mayor for varying amounts of time. The Rhodes family were involved in various mill concerns in the aream and are well known. William was also known as a strong athlete and a good sportsman, being the president of the Glossop Cricket Club for a while.

So there you are – the more you know… or less, in some cases.

The chapel/Sunday school continued in use until Easter Sunday 1968 when it had its last service. It is now known as the Spencer Masonic Hall, and is where, from 1973 onward, the Freemasons Lodge of Hadfield 3584 have met on the first Thursday of each month. And at some stage it was up for sale – the sales brochure can be seen here (complete with interior view!). It’s a lovely building, but very neglected and tatty on the outside, and it’s a bit of shame that something more isn’t made of it.

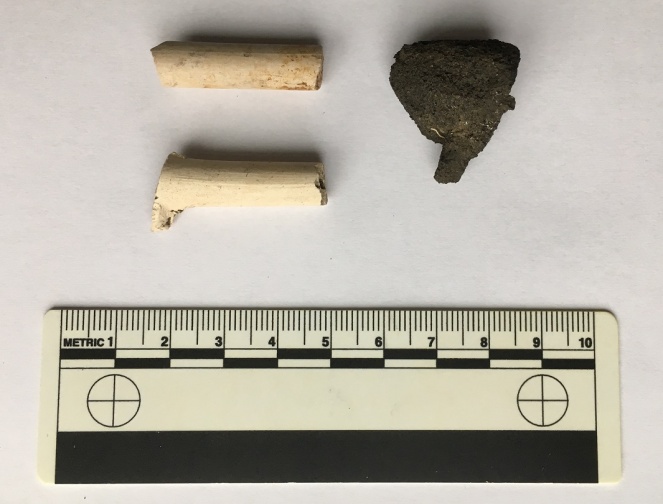

The pottery, then. Obviously it would be nice to find something Roman, but sadly no such luck. Instead, we have a selection of Victorian material, which might be the remains of household rubbish from the houses that once stood there (see above map), but equally might result from the process of nightsoiling. On balance, it is probably the former – there is no arable land in the area where I found the pottery, and the edges of the sherds are still sharp in some examples, and when pottery sherds are ploughed, the edges become rounded. There is nothing too exciting, but nice to see.

Top row, left to right: A shallow dish or saucer, transfer printed, and probably late Victorian, but difficult to date. Next to that are two sherds of a large Victorian cooking pot, very characteristic with thick walls, a black glazed interior, and a plain glazed reddish-orange exterior. They are made that way so that the heat can transfer through the unglazed side easily, but the glazed interior means that it is waterproof, and so holds the liquid well; quite clever really! Next is a willow pattern plate – very boring, but is patterned on both sides, so is from an open bowl type of vessel. Next, a glazed earthernware pot with grooved exterior – it’s probably a storage jar or something similar.

Middle row: Victorian glass fragment (the greenish/bluish tinge gives away its date), with a raised letter ‘T’ – clearly a company name or similar. Next, a plain sherd from a flaring rim from a soup bowl or similar; possibly early Victorian, as it has a slightly creamy opalescent glaze. Next, a handle from something – cup or bowl. Next, an early Victorian sponge ware sherd – the blue pattern actually printed, potato-like, on a sea sponge. This is the base to a bowl of some sort (base diameter is 12cm, so not huge), and judging from the wear on the ring foot, was a much used and loved bowl before it was broken. Next, a sherd from a large cup or similar (c.15cm diameter), with transfer printed decoration. After that is a blue and white striped fragment, probably from a cup or similar. Next is a stoneware fragment from a storage jar or similar, fairly bog standard (there is some discussion of the type and the method here). End, is a clay pipe stem (from toward the bowl), and has a some nice paring marks on the body, but is fairly boring stuff (although I do love them).

Bottom row: All featureless white body sherds.

As I said, overall a fairly standard, if uninspiring, collection of Victorian pottery, and almost exactly as one would expect to find (although I do like the spongeware!). The best find, however, was found by Master Hamnett amongst the rubble and rubbish outside the Masonic Hall.

This was pretty much my childhood – plastic soldiers at a 1:32 scale. Whilst this one is not Airfix, it is still a good quality World War 2 figure – possibly Polish or Russian to judge from the helmet and gun. He’s lost his foot, and his stand, but to his credit he’s still fighting. Interestingly, he was also painted at some stage, too, and not professionally, so I think he was a much loved toy (if anyone recognises it, I’ll happily post it to them… I still mourn the loss of some of my soldiers!).

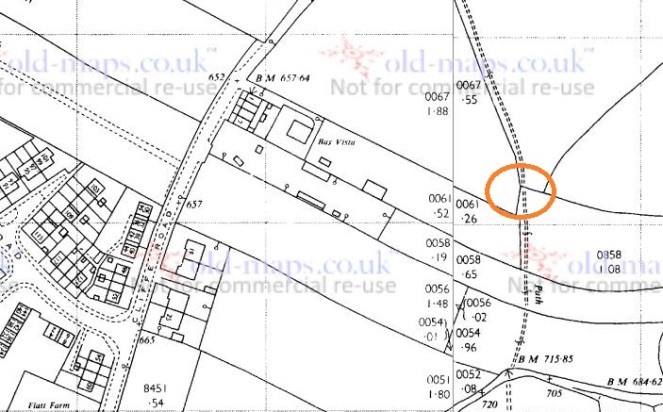

Of course, it wouldn’t be a decent post without a benchmark. On the original path there are three on the line of the track – from the top, a third of the way down (640.7 ft above sea level), one half way down (609.1), and one at the bottom (568.6).

The 1969 map (post Whitfield Avenue construction) has three benchmarks, but are of different heights (641.5, 601.5, & 564.9), and with this last on a now no longer existing ‘public convenience’ at the bottom of the road. Presumably they were re-surveyed and marked when the road was built, as the evidence of the carving seems to indicate. The only one that is still extant is the middle of the three, the others seem to have disappeared, alas.

So, a lot of history and archaeology of a single road were explored on a single afternoon

And, of course, we flew a kite, which was the best bit!

Well, that turned into a much larger post than I anticipated… who knew a 1960’s built street could be so interesting? Comments, as always, very welcome.

More soon, but until then, I remain.

Your humble servant,

RH