As I have said many times before, I do love alliteration. What ho! and all that. I trust you are all keeping well in these odd times? Well, now this is a monumental post – it is precisely three years to the day that I made the first post on this blog (you can read it here if you want). When I first started it I had no idea what it was going to be, other than I had some interesting bits and pieces that I wanted to share, and which I thought other people living in Glossop moght be interested in. The blog is still pretty much that in aim – bits and pieces – and I was right… there are lots of you out there who seem to enjoy the ramblings of a man who gets excited by bits of old rubbish. So thank you, you wonderful people, for reading, and here’s to many more blog posts. Now, on with the show. RH

During the lockdown, Master Hamnett and I have been taking a daily constitutional up and around what has become known as the “secret passageways”. Overgrown and wild in places, even for a man of modest size such as myself it is a mysterious place, but to a 4 year old it is indeed another world. Naturally, I have been keeping an eye open for bits and pieces of history, and I think I have a story to tell. Possibly. Well, I certainly have some pottery to show, so there’s that!

The route we walk is essentially along Hague Street, down one track to Charlestown Road, along, and then up another back to Hague Street. We often continue on and round if it’s not raining, but always walk these paths, which I have helpfully marked Tracks 1 and 2 on the map below:

The tracks and immediate area are more clearly shown on the 1968 1:2500 map

The tracks are interesting in themselves in that they are once again an example of what I call the fossilisation of trackways – they are older tracks that no longer perform a function as such, but are preserved as footpaths. Certainly in this case as it makes no sense to have two tracks mere metres apart going between the same places. Instead, I think they are preserving the memory of a single older track, which I suggest below is Track 2, potentially the more interesting of the two. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Track 1 runs down the side of this house, which was originally a pub called the Seven Stars (hence the sign on the door frame, although the sign above the door is a mystery… if you are reading this and own the house, could you tell us?).

I know nothing about this establishment, but it was probably a beer house. As a reaction to the widespread and dangerous consumption of cheap gin – the so-called ‘Gin Craze’ of the late 18th century – the government encouraged more beer drinking (beer being considered relatively healthy) by allowing householders to open up their houses to brew and sell ale. These private houses became known as beer houses, and the individual paid a small fee to the local magistrates in return for an annual license allowing them to sell beer, but not the wines or spirits that the normal pub or inn could. If anyone has any information about the Seven Stars, please do get in contact.

Just here is a series of upright stones presumably placed to stop horse riding or cycling. The gap between them is very thin; I might have put on a little weight during lockdown, but even I had to squeeze through.

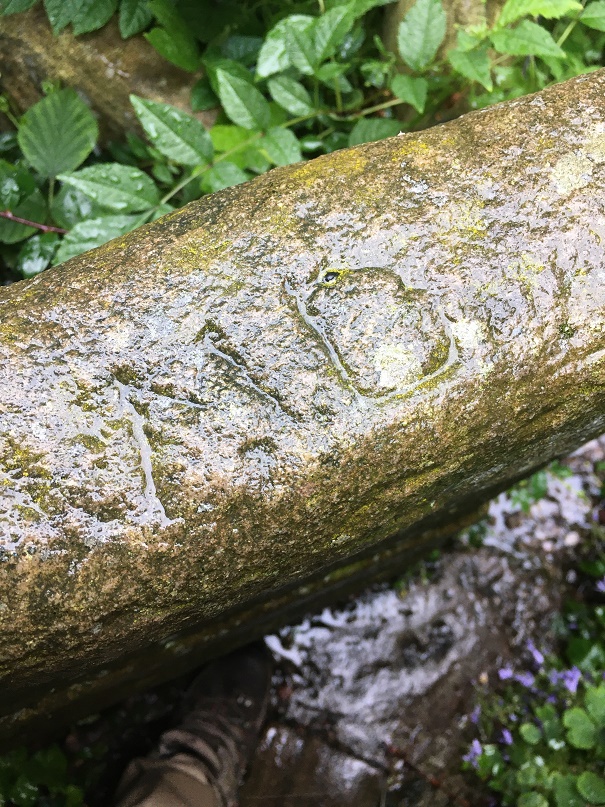

Carved onto one of these uprights are the intials ‘M.D.’ – I must have walked through these 100 times and never noticed the letters before, but the light and the rain were just right this time.

Further down the footpath I noticed a reused quern or grind stone – possibly Victorian, but I suspect earlier – being used as a coping stone for the wall. And why not? It’s the perfect shape, and may well have been hanging around for centuries after being used to grind wheat into flour.

About halfway down, you come face to face with more of those upright stones, although in this case I can only assume they were put there to stop a headless horseman! Honestly, they are quite unnerving.

The path continues:

Until we arrive at Charlestown House, and the Charlestown Works that were – now demolished and awaiting houses.

So, here’s the pottery:

Top row, from the left: a base of a saucer or small plate; a huge chunky handle belonging to a large jug; a base of a glass jar or jug, or possibly from a tankard – it’s nice and decorative, but not expensive. Next is a fragment of a pedestal footed drinking cup, which is again fancy, but not especially expensive, it being just glazed earthernware. Then there is a rim to a large plate of some sort, being about 30cm in diameter.

The lower row from the left: a fragment of a stoneware bottle, a chunk of a pancheon, and a fragment of a manganese glazed jug or similar thick walled vessel. Then we have two pieces of blue and white earthernware, and a base of a tea cup. There is nothing massively interesting, and it all seems to be Victorian in date, as we might expect… except for the manganese glazed jug! This is, I think, earlier – perhaps early 18th century. It’s quite characteristic, and although there was a revival of manganese glazed pottery in the Victorian period, this glaze is of relatively poor quality, and the fabric (the actual clay of the pot) is quite rough, both of which suggest an earlier date. Then there is this lovely bit of pot; it’s a china dove, shaped to fit onto what would have been a tasteless Victorian jug or bowl – you can see the flat bit where it was joined to the vessel it flew away from.

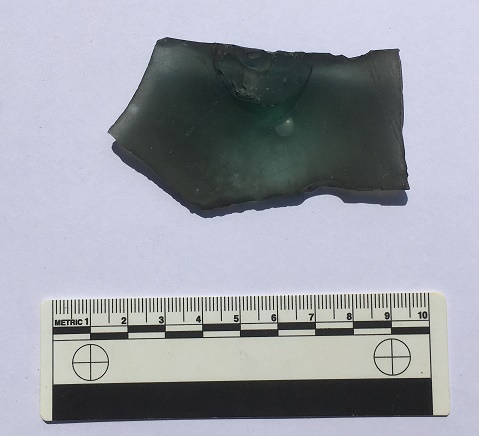

Then there was this:

A screw bottle top, probably from a beer bottle or similar, and dating to the early 20th century. I love these things, and have blogged about them previously – here, for example. Unusually, this one doesn’t have the drink makers name or logo on the top, just the name of the bottler – R. Green of Leigh.

Moving on to Track 2, there is a noticeable difference between the two. This one is more of an actual track; it is certainly wide enough to drive a horse and cart down it, and it seems to have had a surface at some stage. It is also deeply worn in places, which can be suggestive of an older trackway.

I’d love to put a trench across this track to see how it was made up.

Further on, it has what seems to be a late 19th or probably early 20th century cast-iron streetlight, which is interesting and spookily out of place now, but suggests strongly that it was used as a ‘proper’ track until fairly recently.

Right next to the streetlight is a gateway into a seemingly random field, and a benchmark on the gatepost – it’s been a while! This one – 616.77 above sea level – is a late addition as it is only marked on the 1968 1:2500 map. There was another benchmark marked on the opposite side of the track – 622.6ft above sea level – but it’s long gone (you can see it in the map above).

The track continues until daylight is reached.

The top of the track, where it joins Hague Street again, is the site of the original Whitfield Methodist chapel – it is visible on the 1880 1:500 OS map:

Built in 1813, it had seating for 200 worshippers, and at one time was the home of the pulpit from which John Wesley had preached in New Mills (as discussed in this post). There are more details about the chapel on the Glossop Heritage webpage.

It was demolished in 1885, and the site is now occupied by a private house, but there are some interesting re-used stones on the trackway which almost certainly came from the chapel. The one indicated by the arrow in particular seems to have been a window frame – originally it would have laid upright, and you can see where the wooden frame was bedded in, and possibly a cross bar set into the stone.

A closer look reveals what might be a mason’s mark. Possibly… but then I really rather badly need glasses.

So then, the pottery:

Top row, left to right: a fragment of a large stoneware vessel with a cream glaze. I have photographed it showing the interior – it is roughly finished, and you can see wiping marks, and it probably came from a large cider flagon.

Next is an annular ware bowl or similar type, with the characteristic horizontal linear bands around the rim and below. Abrim from probably the same vessel is above it. Despite it looking 1950’s, this stuff ranges in date from the mid-18th century to the late Victorian; this is, I think, early 19th century. Next is a sherd of a cream ware jug, this being a part of the spout – you can tell by the twisted curve of the rim – again, early 19th century. Next is a stoneware flaring rim to a large jar, Victorian in date. Next we have a sherd of black glazed pottery which, I think, might be 18th century in date – the glaze seems to be lead based, which it isn’t in the Victorian period, and the fabric is very red, which is also common in Black Ware of the 18th century. I’ll post some more about this in the future – I’m actually trying to put together a crib sheet for pottery identification for this part of the country which some of you might be interested in (I know, I know, stop groaning… you don’t have to read this blog, you know. And I did say ‘some of you‘!). Beyond that is a fairly uninspiring selection of Victorian sherds at which even I pale!

Track 2 is odd – there’s summat rum about it. It has the air of a deserted roadway that was once of some importance, certainly important enough to have a substantial gateway and a streetlight on it. Looking at it, and thinking about the fossilisation I talked about above, I wonder if this was the line of an earlier track, perhaps even the medieval road that led from Whitfield to Lees Hall (which is circled in green in the first above – see, I told you it would all become apparent!). The hall, though 18th century in date now, stands on the site of a medieval manor house, possibly even the original manor house of Whitfield mentioned in the Domesday Book. It was certainly important in the medieval and early modern periods as the seat of the Manor of Glossop, where tax and tithe from Glossop and Whitfield was taken – first to the Earls of Shrewsbury, and then, from 1606 onwards, the Howards. The road from (Old) Glossop came through Cross Cliffe (discussed here), along what is now Cliffe Road through Whitfield, and from there down this track to Lees Hall. One less obvious part of it may be the footpath indicated by the orange arrow in the map above; I don’t think that it is the exact route the track would have taken, but it again ‘preserves’ the way in the landscape. I would suggest, then, that Track 2 is either this hugely important road fossilised into the landscape, or it broadly follows the line of that road which no longer exists. A point that may also support this is that on the 1968 OS map, also above, the track is marked by a series of ‘Boundary Mereing Symbols” (they look like lolipops – circles on sticks) which apparently indicates that it is the boundary of a parish or parish council (here, for an explanation). Boundaries, or meres, often use ancient and established objects or features to lay out the area that is bounded – an old track is a very common and perfect example of this type of feature.

This part of Glossop – I suppose technically Whitfield – is very interesting.

Right, that’s your lot for today. As always, please feel free to comment – even if it’s simply to tell me I’m talking out of my hat. I have more that I am picking away at, but until then stay safe and look after each other. Oh, and happy anniversary.

And as always I remain, your humble servant,

RH