Ho! Ho! And if I might dare, What Ho! A shortish one today, and actually one that is something of a relief, if I’m honest. Like the last post, this one has been years in the making, but this time for all the wrong reasons… all will become clear in a moment, but for now let’s crack on.

As the title suggests boundaries are today’s topic, apt as we hurtle to the Winter Solstice and the shortest day – that anciently observed boundary between the old year and the new. Boundaries such as these are often held to be dangerous places as they are a liminal space – neither one thing nor another, but somewhere in between. However, boundary stones in particular I find fascinating and strangely appealing objects; there is something very grounding about them in that they mark in a clear, permanent, and fixed way, an imaginary line. On one side ‘X’ and on the other ‘Y’, and there is no argument – the somewhat liminal boundary is made visible and real, and so it is the case with our stones today – three stones placed on bridges over various waterways delineating the townships that make up Glossop

All three, it seems, were carved and installed at the same time, and all are quite old – early Victorian. The first of the stones is the easiest found – Victoria Bridge in the centre of Glossop.

And here it is in real life.

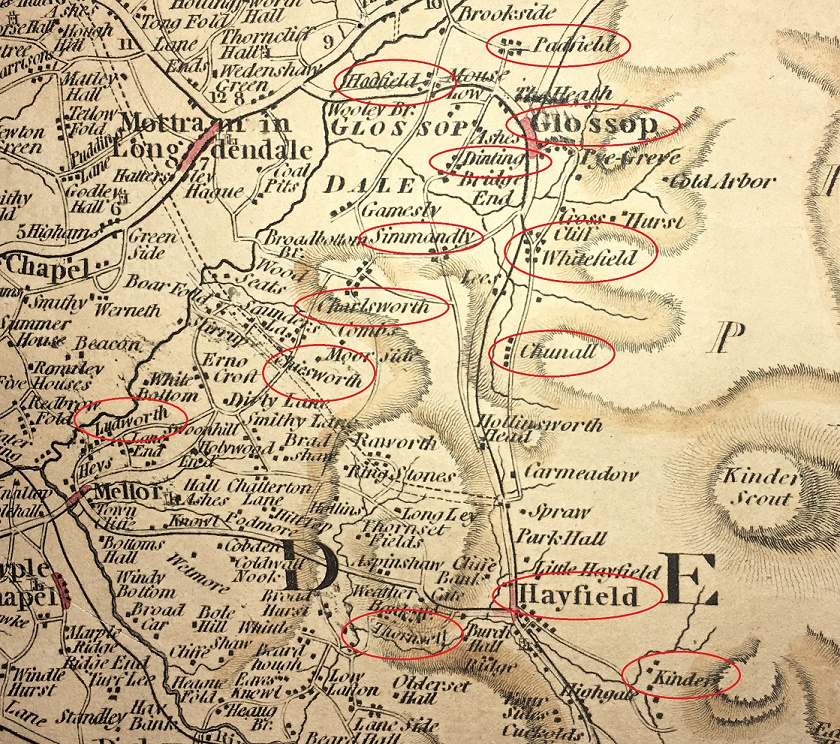

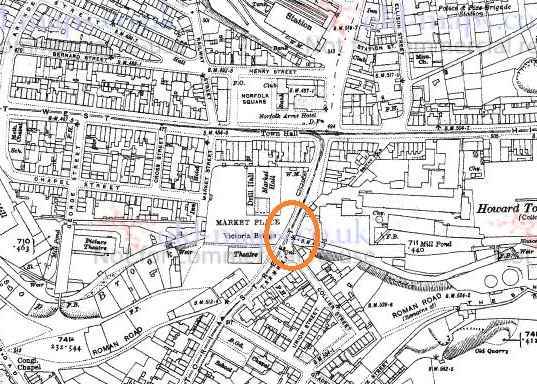

The bridge, and the stone, stand over Glossop Brook, which disappears under the market place and carpark, and the line carved between the words Glossop and Whitfield is the centre line of the brook below. Victoria Bridge was built in 1837, the year Queen Victoria ascended the throne, hence the name. This new bridge replaced an old and narrow hump-backed pack-saddle one. Indeed, the original line of the road that led over the bridge, down Smithy Fold, and along Ellison Street is traceable, and is preserved particularly in the buildings of the Brook Tavern, Cafeteria, Glossop Pizza, Balti Palace (all built in 1832). I have a blog post almost finished that looks at this area in more detail, so I won’t go into it here.

Looking closely, the inscription “Victoria Bridge” and the date “1837” are in a different font and slightly larger than the other lettering on the stone, and are more cramped, and it seems they were added at a later date. Indeed, compare this stone to the one below, and you can see they both once looked the same.

And of course, it wouldn’t be the Glossop Cabinet of Curiosities without a bench mark, this one on the bridge and just to the left of the boundary stone.

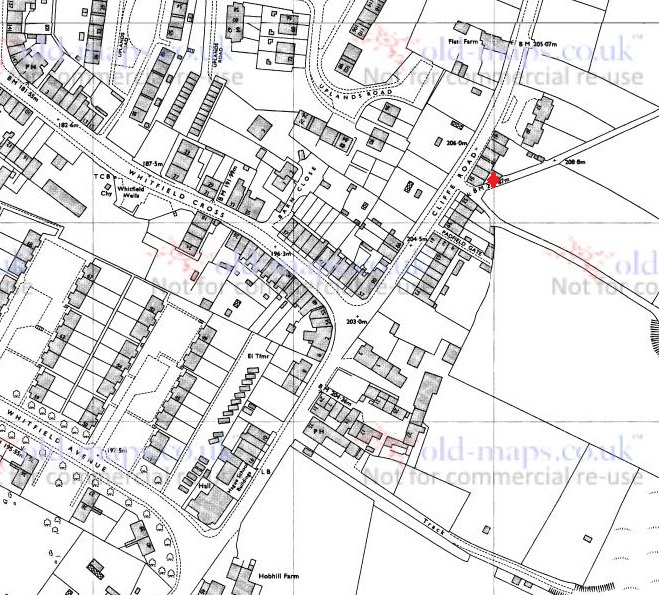

The next stone is to be found on Charlestown Road, on a bridge over Long Clough Brook – it’s very much a blink and you’ll miss it kind of affair, even if you are walking.

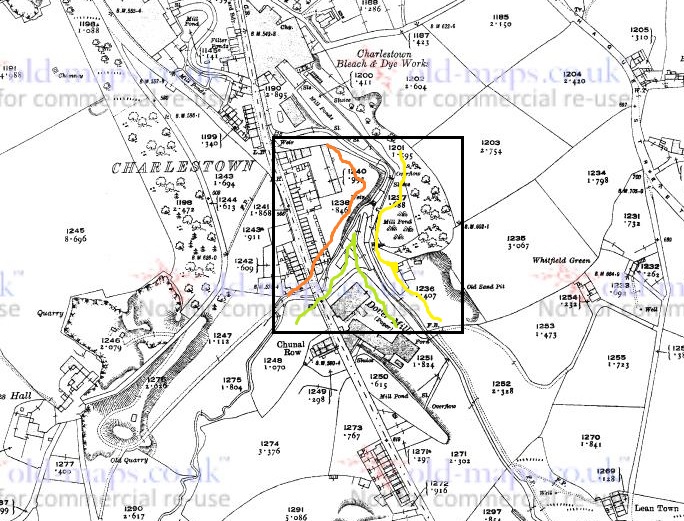

This stone follows the same formula as the Victoria Bridge stone, but is slightly rougher in execution. It seems to have been reset into a rebuilt stone wall at some stage, as it doesn’t really match the coarse surface of the stone around it, and this resetting might explain the cracking. It also has an inexcusable mistake… there’s a bloody apostrophe after ‘township’! It should read ‘TOWNSHIPS’, the plural of township, but instead it reads that ‘Township’ owns something called an ‘of Simmondley and Whitfield’! Also, although it states that this is the boundary between Simmondley and Whitfield, it technically isn’t. This is the border between Chunal and Simmondley, but it seems that for administrative purposes, Chunal and Whitfield were often lumped together. The confluence of Bray Clough (from Gnat Hole) and Long Clough Brook (just east of the boundary bridge) is actually the meeting of the three townships of Chunal, Simmondley, and Whitfield, here:

So far, so good.

Now, the third and final stone was a bit more of a mystery. According to Neville Sharp (Glossop Remembered p.184 – a great book, by the way, well worth seeking out – here for example, but order it from Bay Tree Books on the High Street, of course), a stone similar to the one on Victoria Bridge stood on the bridge over Hurst Brook which forms the north eastern boundary between Glossop and Whitfield. That is until it was washed away in a flash flood.

Then, whilst doing some research, I came across a reference to the stone and made a note in my notebook that until at least 1977 the stone stood next to the entrance to Golf Course. Annoyingly, I didn’t take down the reference and it’s taken me 3 years to track down the source of the information. Three years! Such is the level of detail and dedication I devote to this blog in order that you, gentle reader, can revel in such a fascinating subject as “bits of old plate” as it was once described by the person who runs the ‘Official Glossop‘ twitter account. Honestly, the nerve of some people…

So I re-found the source – this website – and blow me if it didn’t have a link to photographs of the stone taken in 1977:

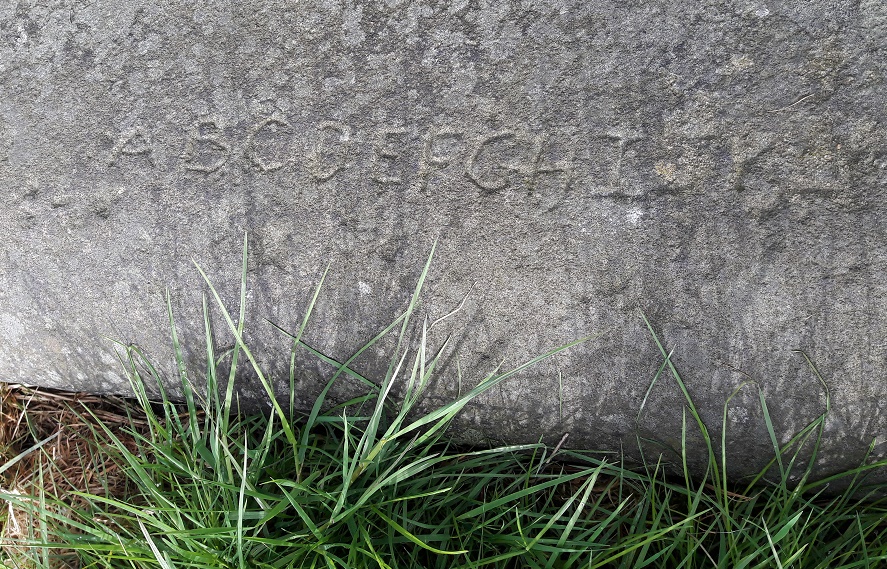

The stone was presumably recovered, in its broken state, and set up on the side of the Golf Club entrance, and whilst it doesn’t look like there is a lot left I went to have a look.

Alas… the stone is no longer there. I had a good look around at all the stones that might be a possibility, but to no avail. I suspect that someone has taken it – it was a nice piece of stone after all, but it is a shame. All is not negative, though, and from the 1977 photograph we might suggest where it originally stood; the fact that the fragmentary word ‘Glossop’ is visible at the left hand end of the stone means that it could only have stood at the eastern side of the bridge, closest the golf course, for it to make geographic sense – Glossop is north, Whitfield is south at this point. Here, in fact:

Its fragmentary nature also suggests that more of it lies in the stream bed – I had a look, but couldn’t see any likely stones, but perhaps next summer I’ll have a poke around.

Right ho, that’s all for this time. Hope you enjoyed a ramble around the boundaries, and in fact I am writing a blog post that actually covers the boundaries of medieval Glossopdale based on a 13th century perambulation. I’d also like to do another that looks at the boundaries of all 10 townships of Glossop as they are in the Domesday Book, which could be a bit of fun. ‘Could‘ being the operative word here. And ‘fun‘ being an entirely subjective concept, I realise. But you, kind and gentle people, know what I mean… after all, you’re reading this. Please drop me any thoughts or hints, even to point out my mistakes, or the fact that I need a haircut. Take care of yourselves and each other, have a very merry Christmas, and until next time, I remain.

Your humble servant,

RH