What ho, people, what ho! I hope you are all well and are suitably recovered after the Christmas season?

A word heavy – and pottery light – blog post today (those of you cheering at the back… don’t think I can’t hear you). It’s also a little speculative, too. Archaeology, and indeed history, rely on interpretation, and how we understand and use the evidence presented to us affects the story we tell. We don’t always have all the answers, and we do make mistakes, but speculation is essential, so let’s imagine… today’s story is of Anglo-Saxon Glossop, so buckle up!

Now, I love a good placename or two. Ask anyone who knows me and they’ll say “Oh yes, old TCG loves a good placename or two. He really loves them”. And then they’ll give a look. That look. I’ve never worked out what it means, that look, but shortly after the person who asked will give a nod of recognition, and say something along the lines of “… oh! I see!” And then both will turn to me, cock their heads and smile kindly, and give me an entirely different look, one of benevolence and calmness, that seems to say “awww, bless you“. Worryingly, I often get the same look from Mrs CG and Master CG. Anyway, moving swiftly on.

So then, Glossop in the Anglo-Saxon period; the Dark Ages, so-called due to the lack of historical knowledge. This is, truthfully, something of a misnomer, and our understanding of the turbulent period of 600 years between the Romans ‘leaving’ (410AD) and the Norman Invasion (1066) is becoming clearer all the time… mostly. For our own area, though, it is still by and large a black hole of historical detail. We know something was here during this time – we have Roman (certainly early Roman), and it’s highly unlikely that the military abandonment of Melandra (probably later 2nd century AD) meant that everyone left the area, especially given the location at the head of the Longdendale Valley. The Domesday survey of 1086AD lists 10 villages hereabouts, so there is definitely something here 600 years later that didn’t just spring into being overnight.

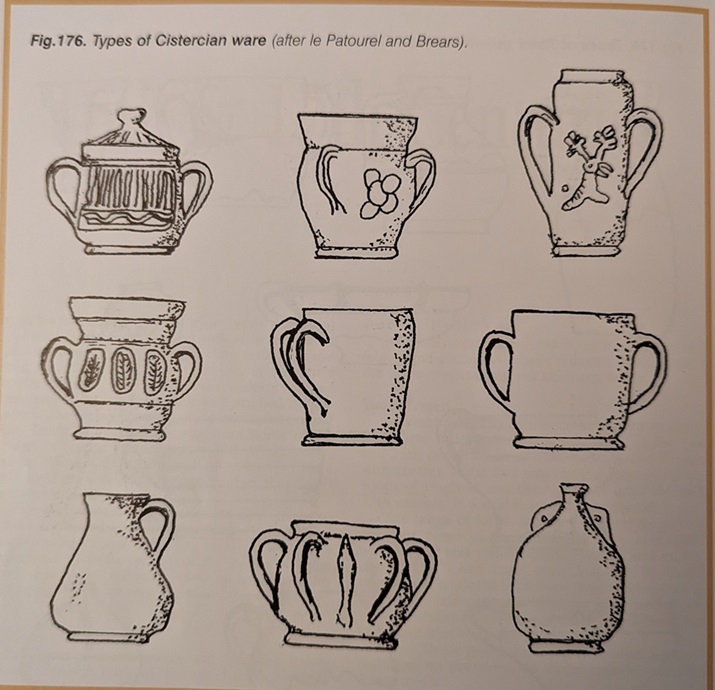

Phil Sidebottom has recently written an excellent book called ‘Pecsaetna‘ (and do feel free to order from our marvellous local bookstore – Dark Peak Books) which looks at the Anglo-Saxon tribal grouping that lived in this area – the Pecsaetna, or ‘Peak Sitters’ – of which we Glossopians should rightfully be proud to be a member of. It doesn’t cover Glossop as such – we are very much on the periphery of what was already a backwoods – but it is a great read for anyone who is interested in what was going on in the Peak District during this period. But the fact of the matter is that there is very little archaeology to be found relating to these 600 or so years; to be precise: 3 stone crosses (the 10th century Mercian Round Shafts – Whitfield Cross and Robin Hood’s Picking Rods), and placenames. That’s it. We don’t even have any pottery to look at, as it seems that in this area people were largely a-ceramic – that is, they simply didn’t use pottery. Imagine, a world without pottery… now that’s a sobering thought.

Some of the placenames in the area I have covered before (the main Domesday ones, for example), but some others I haven’t, and in particular, Mottram (in Longdendale), I find particularly interesting. It is probably derived from (ge)mot (a meeting or assembly) and either ‘treum‘ (tree or cross) or ‘trum‘ (a place or space). Either way, it is almost certain it describes a place where meetings took place, marked possibly by a tree or a cross. These meeting places – or ‘moots’ – have been described as the “cornerstone of Anglo-Saxon governance”, in that various Anglo-Saxon statutes dictated that these councils met publicly every four weeks at these moots to discuss local matters – think of them as local councils and magistrates. They are important places, often marked by a prominent feature – often a cross or a tree – and were in an elevated position – a hill, or lower slope, overlooking much of the land. The one at Mottram fits the bill perfectly, and it was possibly the extreme north eastern moot place of the pre-conquest Hamestan Hundred, right on the border of the land (the River Etherow). All very intriguing stuff, and has relevance for Part 2 of this Dark Age speculation – coming soon.

However, one small group of placenames got me thinking recently, and these are those that have a Scandinavian origin, and by Scandinavian I mean, essentially, Viking.

Soooo… Clan CG went on a week-long jaunt in Norway last summer. And wow, what a country! Beautiful, full of life and history, nature and culture… there is something about Scandinavia that really appeals to me. And at every stop (we hired a campervan) there was wild swimming. Marvellous stuff – the clean water of the fjords; fresh, invigorating, life affirming, health giving. I mean to say, not for me, obviously! I dipped a toe or two in… but brrr – far too cold! So I stayed on the bank and cheered on Master and Mrs CG, who seemed to enjoy it!

One of the places we visited was Trondheim, a lovely town right at the top of an enormous Fjord, next to an an enormous mountain; scale is a thing in Norway, and I’m sure these landmarks would be puddle and hillock respectively to the locals. We parked up a hill out of town and walked in, and as we approached a crossroads, my sherdy-sense tingled. No, not sherdy-sense, something else. And then I saw it… the road names. We were walking down “Langes Gate“, and we had just crossed “Storgata“, and before I knew what was afoot, my brain had forced out a mighty “what ho!” which might have alarmed the natives somewhat.

I recognised the word ‘gate‘ or ‘gata‘ from British placenames. Scandinavian in origin, meaning street or road, locally it can be found in Doctors Gate and Redgate, and this reminded me of a pet theory of mine, and I began to hastily scribble words down back in the campervan that evening, a glass of stuff that (expensively) cheers clasped firmly in hand.

Of those Domesday placenames I looked at, one really stuck in my mind, niggling with possibility. Truthfully, sometimes these things do, and I don’t know why; they shimmer and make a noise in my head, drawing attention to themselves more than others – I assume it’s my brain making connections, rather than an objective noise, but you never know… and once again, I feel I have overshared!)

Simmondley. First mentioned in the Forest Proceedings of 1285 as ‘Simundesleg‘, and then later as Simondeslee, the origin of the name is “the clearing (or ley/legh) in the forest belonging to a man named Sigemund (Old English) or Sigmundr (Scandinavian [Viking]): Simmondley. Ok then, so we have a possible ‘Viking’ name, but there is no evidence for Vikings hereabouts. Or is there? And this is where is started to get interesting.

The Vikings – and all manner of Scandinavian folk – first began raiding the coastlines of England en masse at the start of the 9th century. Eventually, the raiding stopped, and it became a steady flow of immigration, settlement, and farming – swords to ploughshares, and all that. It’s a big country, there was a lot of land, and so they stuck around, and in doing so they changed not only the language we use, but also the placenames of the area they settled – in particular, the area that became known as Danelaw – where they were allowed to keep following their own laws as long as they were loyal to English (Saxon) kings. The exact limits of Danelaw is a bit of an unknown, but it roughly stretched from Essex to Northumbria, and across to the Mersey – this is lifted from the Wikipedia page, and Danelaw is in red.

As you can see, whilst we are on the border, we Peak Sitters are still within Anglo Saxon (English) controlled lands, hence we don’t have many Scandinavian placename elements hereabouts, those name endings such as –thorpe –holme, –by, and -ton that are common enough just over in West Yorkshire, but not at all here. It has been suggested that the limit of Danelaw, whilst flexible, may have been the River Etherow and Derwent Valley, making us very much at the limit of Saxon land (If you are really interested, the always excellent before1066 blog has a great read about the Danelaw in our part of the world – you can read it here). But this area is firmly Saxon in language, and thus in placename.

Or so it seemed… and here it gets speculative.

Whilst the area was never settled properly, Sidebottom notes that a small number of areas in the Peak District have Norse derived placenames in their landscape, perhaps indicating the presence of settlers (Monyash, for example). These, he suggests, are Hiberno-Norse settlers – in essence, Vikings who had settled in Ireland, but were expelled from there in the early 10th century and settled in the area around Chester and the Wirral. From here, they moved east and were allowed land to the east of Manchester, specifically in the marginal western slopes of the Pennines. Hmmm… east of Manchester, in the slopes of the Pennines…. does that description sound familiar? Yeah, it rang a bell with me.

These were not true Vikings, and were actually 2nd or 3rd generation immigrants, but they would have spoken their language, and whilst they might not have named any existing settlements as such, they used their dialect words to name the elements of the landscape, and these don’t often change.

It was the origin of the placename Simmondley that initially rang the bell of possibility. It is first mentioned in the Forest Proceedings of 1285 as ‘Simundesleg‘, and then later as Simondeslee. The meaning of the name is “the clearing (or ley/legh) in the forest belonging to a man named Sigemund (an Old English name) or Sigmundr (a Norse name): Sigemund’s Legh = Simmondley. We assume it’s Saxon, because there are no Norsemen around here… but what if there were? And then the second bell was rung in Trondheim… Gate. In the Simmondley area, this is found as part of Hargate (as in Hargate Hill), but are there any other placenames of Norse origin in the Simmondley area, I wondered?… and promptly disappeared down a rabbit hole that I’m still not sure I have come out of!

So then, there are six Norse placename elements that occur in the Simmondley area:

- Simmondley itself, we have already discussed, but its possible meaning is the ‘clearing in the woods belonging to Sigmundr‘. Sigmundr, and presumably his family, may well have arrived from Cheshire way, and cleared a smallholding in the woodland, where he would have set about naming things in his native tongue! Interestingly, Simmondley isn’t in the Domesday survey, possibly because it was simply a farm and too small to be recorded as its own settlement, so was just recorded under Charlesworth generally. We also need to realise that it may have only been in existence for 100 years in 1086, possibly even less.

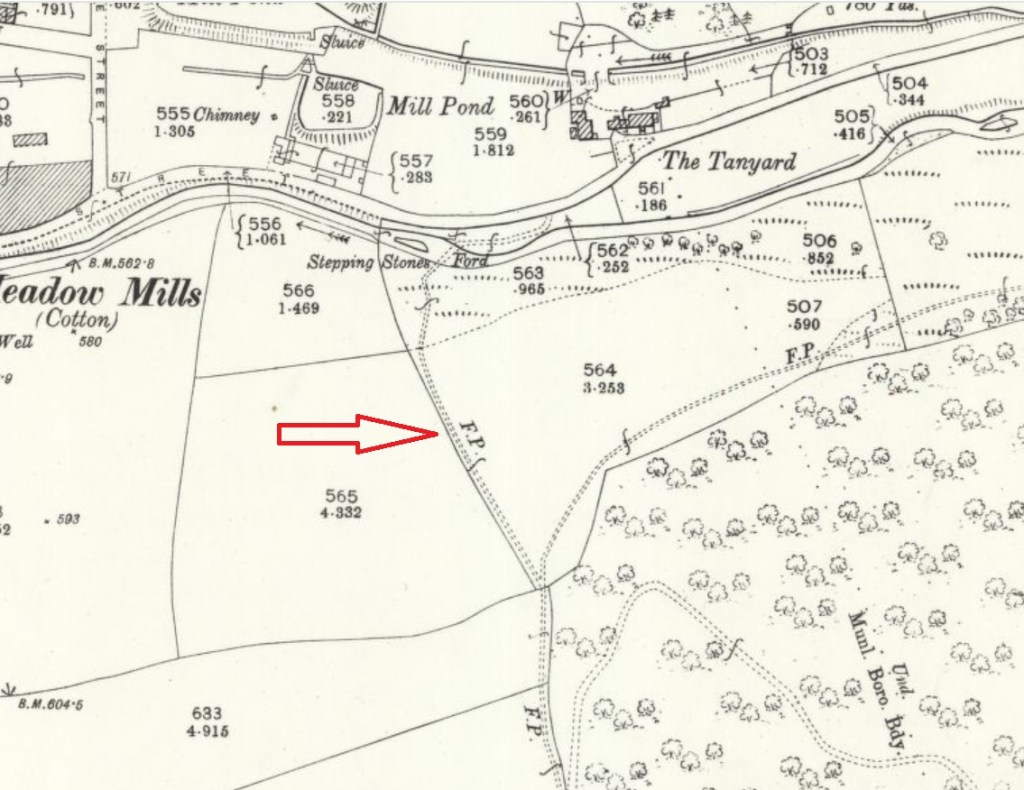

- Sitch – here used in Sitch Farm on Monks Road directly up from Simmondley. Sitch is derived from Old Norse ‘Sik‘ meaning a small stream, especially those flowing through flatland and marshy areas. It occurs elsewhere in Glossop: Wall Sitch by St James’ Church (discussed here), and Back Sitch, a footpath in Old Glossop.

- Nab – here used in Whitley Nab. It is derived from the Old Norse ‘Nabbr‘ meaning a projecting peak or hill, which sums up the Nab perfectly. The Whitley (or Whiteley) part is presumably referring to a clearing; white here meaning without colour.

- Royd – here used in Hobroyd. The word – meaning clearing – is not exclusively Norse, as it is found in Saxon places too: the root is the same for both German and Norse. But it is often used as evidence for Norse influence when found with other Norse placenames. Interestingly, the word ‘Hob’ here means a hobgoblin or other supernatural creature; Hobroyd is the ‘clearing belonging to the goblin‘. Bizarre.

- Storth – here found in Storth Brook Farm and the adjacent Storth Brow Farm. The word Storth is Old Norse and means a young wood or plantation, possibly one planted.

- Gate – here found in Hargate Hill Farm. Gate, from the Norse, Gata, meaning road.

This last one, the one that started this whole merry dance, is for me the cherry on the cake, and what just about convinces me. It gets its first mention as Hargatt in 1623 in the burial record of Widow Robinson. Now, 1623 is 650 years after the time we are talking about, but placenames stick around, and rarely change; this is why we call Glossop, Glossop: some 1000+ years ago, someone described the area as “oh, you know, Glott’s Hop“… and here we all are, on this website. Perhaps more importantly, church records only go back to 1620 in Glossop – very very late, but not uncommon, so 1623 is only the first mention we have, not when the place spring into being. ‘Gate’ makes sense, but the ‘Har’ element makes little sense, until we find in 1664 it is referred to as ‘Hardgate‘, and we see that this is probably the ‘correct’ name, and that all others are variants of this – the ‘d‘ being an obvious sound to drop.

This got me thinking: Hardgate… Hard Road? And then I realised that the Roman Road from Buxton passes through the area just west of the settlement. Was Hardgate referring to the ‘Hard Road’ of the only decent road in the area, a beautifully built and ‘hard’ surfaced Roman Road, as opposed to the muddy nightmare tracks that the rest of the area was filled with, and which even in the early 1800’s were still being moaned about? I wondered about the word Hard, and on a whim I entered the English word into Google Translate. Do you know what the Norwegian word for ‘hard‘, meaning solid or inflexible is?

‘Hard‘.

Hargate/Hardgate simply means the ‘Hard Road’ in Norwegian. I am convinced this refers to the Roman Road in their native tongue, and that convinces me that this whole ‘Viking’ enclave in Simmondley is a real thing. At least, I’m convinced… for now; I realise I’m not a placename specialist, and that this is something of a stretch. But c’mon…

So the next time you are in the Co-Op buying beans and some bread, remember: “We Gardena in geardagum, þeodcyninga, þrym gefrunon, hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon…” and all that!

Ok, so, I can already hear the army of linguists and placename specialists lighting torches and starting to yell. Truthfully, I’m out of my depth here, but I believe what I’ve written. If you know better, please let me know… I’m always happy to be wrong, as it’s how we learn. But more importantly, if you know of any other Norse placenames in the Simmondley area, please let me know. Part 2 of this post – coming soon – is even more contentious! And in between – probably – is another instalment of the Rough Guide to Pottery… I know you have missed it so. Although the screaming I’m hearing (and swearing… don’t think I can’t hear that too) is a little off-putting. But in l know you are only joking, so as a reward, I’ll put in extra photographs.

Until then, though, look after yourselves and each other, and until next time, I remain.

Your humble servant,

TCG