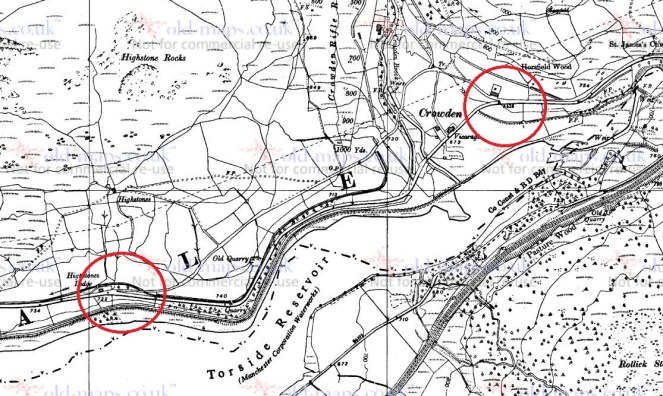

Welcome back for the third and final instalment… it was a very productive walk indeed! The first two are here and here.

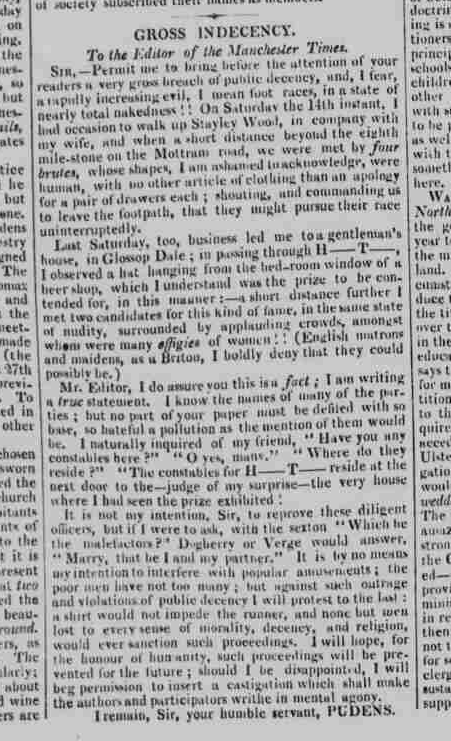

As we continued along the track, we came down, toward the place where it joins Cliffe Road, near where the Guide Stoop is. Here, the wall on the left has been removed, and replaced by a fence, but at the bottom of the track, there is a stump of the wall left, ruined. And spilling out of the wall’s innards, so to speak, I noticed some glass, some pottery and a black tubular object. Well, I could hardly leave them there, could I?

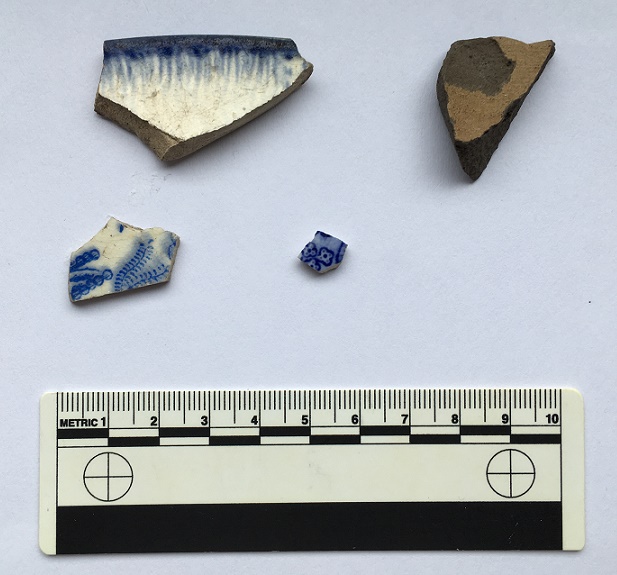

So then, what do we have?

Firstly, fragments of a Codd Bottle.

Invented by Hiram Codd (great name!), he patented the famous design in 1872, and began manufacturing them on a large scale in 1877, or thereabouts. This groundbreaking design was a way of keeping fizzy drinks carbonated using a glass ‘marble’ inside the bottle, with the gas keeping the marble pushed firmly against a rubber seal. When empty, they were often broken open by children to retrieve the marble; here is one I found in my garden a few months ago.

The bottle was broken before it went into the wall, and you can see that different fragments had different amounts of soot and air exposure, causing the variation in colour. I spent a happy 5 minutes gluing this together – superglue really is a marvel! Anyway, here is a complete Codd Bottle, showing its very distinctive ‘pinched’ shoulder/neck, very thick glass, and you can just make out the marble in the neck.

It remained in use until perhaps the 1910’s, when other, more simple, designs – mainly the screw stopper – replaced it as a way of keeping drinks carbonated. Here is an excellent website that talks a bit about them – it is well worth an explore.

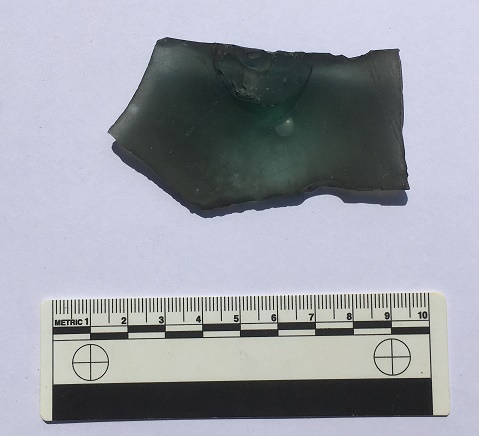

Next is a piece of green glass bottle dating from the 1870’s on, and which probably held mineral water or beer.

This one was moulded, not blown, and has the remains of an embossed decorative shield that would have shown the manufacturer. Each company would have its own design, and usually they were locally made, so it might be a Glossop bottle. Here is a whole example of a bottle showing what I mean.

There is a fascinating website here that discusses coloured glass from a historical archaeological approach, and despite being American in focus, it is very useful, and well worth an explore – it is one I return to time and again for facts and identification help.

Another bottle fragment, this time a concave base, and with an moulded number ’13’ on the bottom.

It has a base diameter of 8cm, is made of thick glass, and judging from the wear marks on the base rim, the bottle was used over a period of time, or possibly used and re-used. Late Victorian is a guess in terms of date (thick glass & greenish hue).

Then there is this…

It is glass, broken, and has a raised bump on one side, centred over a feature on the other side. This feature – visible in the above photograph – is circular, tube-like and hollow, and has an impressed mark in the centre, made when the glass was still soft. The only other features are a pair of parallel lines running diagonally to the right of this central feature, and scored onto the object when the glass was cold. The glass itself is thick, full of air bubbles, and has a greenish tint, all of which suggests that it is old (Victorian or earlier)

I have literally no idea what this is. None whatsoever. Answers on a postcard, please.

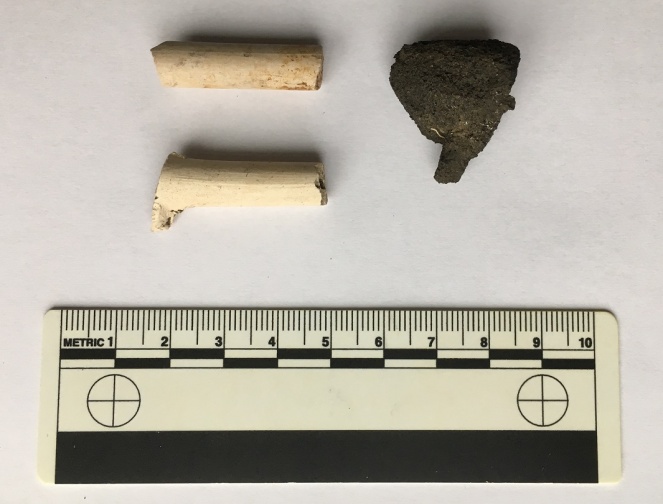

The black object is interesting; on closer inspection, it turns out that it is a pipe stem.

Made from Ebonite (also known as Vulcanite), a type of hardened rubber, it is the bit that fits into the mouth, and through which the smoke is drawn. It is made as a separate part, fitting into the bowl via a metal ferrule – you can see the rounded end in the photograph. The other end, though broken, is of the ‘fish tail’ type stem, flat and wide, and would have originally had a lip at the end. Ebonite is still used for making pipe stems, but was first created by Charles Goodyear in 1839, with the process of making it patented in England by a Thomas Hancock in 1843. It was immediately put to all sorts of uses as a cheap durable alternative to Ebony wood, and from the 1850’s on, it was used in the making of pipe stems (another interesting website here).

So far, so Late Victorian. So what, then, is this doing in the mix?

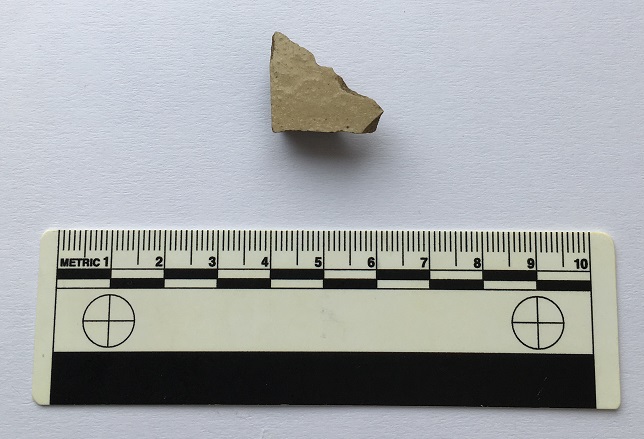

This is Midlands Purple Ware, a type of coarse stoneware. It is hard (fired at a high temperature), purple (though can be more orange or red), and has a large number of black and white inclusions (they look like salt and pepper). It’s very characteristic, and once you know it, you can spot it a mile away. Midlands Purple was made in huge quantities between about 1600 and 1750 (although some sources state its production started earlier, I go with this date for the classic Midlands Purple), although I think this example is late (early to mid 18th century). What is interesting is that this pot was found mixed with the Victorian material – in the top photo, you can see the pipe stem lying underneath one of the Purple Ware sherds. I’ll return to this below.

These fragments (mended) come from the base of a pot, and using the internal wiping marks at the start of the upturn of the vessel wall, I would suggest a base diameter of 25cm, and it probably comes from a large storage vessel, such as this beer container. Most houses and farms would have brewed their own beer as it was cleaner than the water at the time.

So what does all this mean?

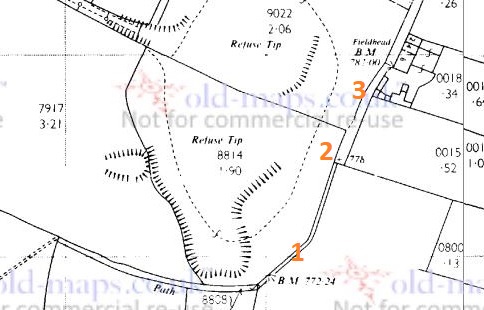

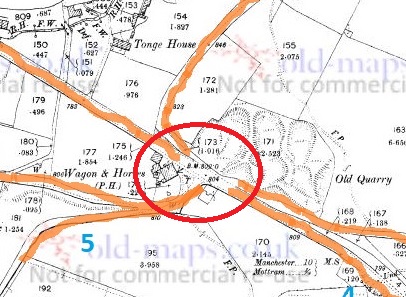

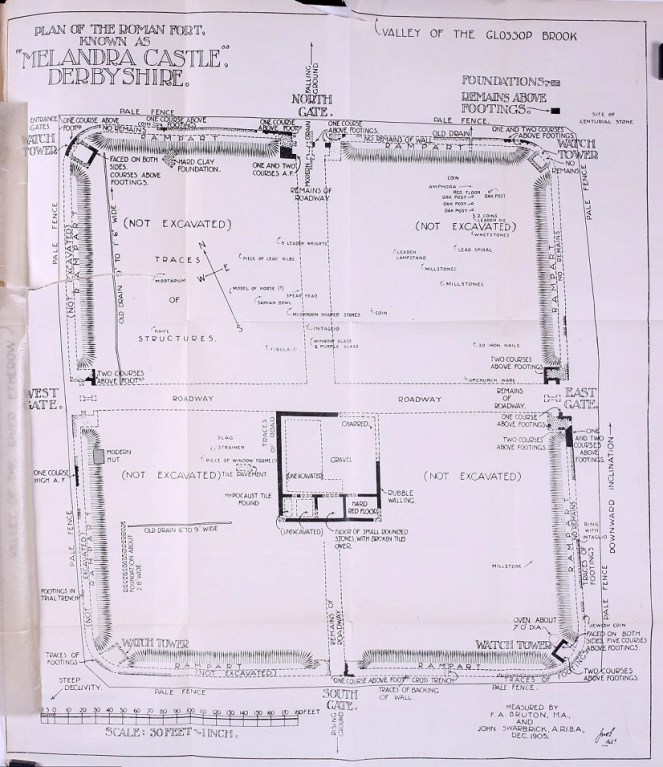

Well, we know that the wall is much earlier than the Victorian glass – it is here on the 1857 Poor Law map of Whitfield, for example – and almost certainly dates from the initial enclosure of the fields and moors in 1813.

The Late Victorian material probably represents a rebuilding episode. The wall itself is still in bad repair, and I think I can detect at least three phases of construction too.

The Midlands Purple Ware is clearly much older than the wall, and is something of a conundrum – what is it doing here? It might represent residual rubbish incorporated into the wall. However, it is perhaps more likely the pot was still in use 100 years after it was made, but broke as the wall was being built in 1813, and ended up used as filler. Possibly. And it was then reincorporated into the wall as it was being repaired in the 1890’s. Again, possibly.

Now here is where it gets interesting.

Why would the repairer of a field wall place a Codd bottle, a beer bottle, and a pipe stem in the wall? Pottery and rubbish is often used as a foundation bedding for a wall at this period (I have a pile from my garden that I need to blog about), but these are high up in the wall. But it does seem that the obvious answer is rubbish disposal. In this scenario, the builder has a break, smokes his pipe, but then accidentally breaks it. He finishes his bottle of fizzy water, and another of beer, then accidentally breaks them both. He curses, then places some, but not all, of the fragments in the wall, along with some other bits and pieces, and carries on building. 100 years later I find it, and here we are.

This interpretation seems fair enough. But it seems a little too convenient – a discrete, neat, bundle, carefully walled up. And the fact that only fragments were placed, not the whole thing. It would also have taken effort to do this, too, when surely it would have been easier to simply have thrown them into the field.

“Hmmm…” I say.

However, there might be another reason.

I have recently been doing research into the tradition of hidden objects within the fabric of buildings (here is a great website that deals with the subject). Shoes, famously, have been found in the roof and around the fireplace of 1000’s of buildings up and down the country, as well as in colonial America and Australia (I have one from the Glossop area that needs to be blogged about). But it is not just shoes, these caches contain all sort of clothes, and indeed all sorts of objects – including bottles, pottery, and pipes – and all dating from c.1600 to 1900.

The term used to describe these caches is a ‘Spiritual Midden’, with the idea being that each of the objects is placed in the cache at the end of its useful life, and is then sealed away and hidden from view in a midden. The study of this tradition is relatively new – bundles of rags and objects when discovered are usually thrown away – and it is little understood beyond a general consensus that they are broadly connected with concepts of ‘luck’ and ‘protection’ from evil or witchcraft. They are believed to be ‘apotropaic’ (that is, they ‘turn away’ evil – I blogged about the subject here and will return to it again, as I find it fascinating). Briefly, spiritual middens seemed to have functioned by making the deposit of clothing and objects the target of bad luck or witchcraft, rather than the people within the house. In a real sense the cache stands for, or personifies, the individuals within, and acts as a lightning rod for any negative energy, safely diffusing it.

The ‘meaning’ of the individual items within the midden is unclear. The shoes, gloves, trousers, and other garments are the most obvious – they are very personal items, and are usually deposited worn out, meaning they have, in a sense, moulded to the individual, and have been imbued with their essence. The bottles are less clear; perhaps connected with ‘witch bottles‘. Bones may relate in some sense to food, and pipes have been suggested as connected with fire, or more specifically fire prevention. This is all speculation, of course, but something is going on with deposits of objects from the early 17th century on, and which lasts until the end of the Victorian period. Perhaps, then, we are seeing a decayed form of this deposition ritual in the objects hidden during the wall rebuild in the 1890’s. Of course, by this time the ‘meaning’ of the caches, whatever it was, would likely have been lost, and the ritual of hiding certain objects was carried out as a ‘tradition’ or ‘thing we do’, or simply ‘for luck’, with none of the belief that drove and informed earlier caches.

This interpretation is made all the more plausible by the fact that the location of the ‘cache’, if such it is, is at the very end of the wall. Thus, it represents either the very first part of the wall begun, or it forms the last section made; either way, the deposition of objects there seems appropriate. There is also the tantalising possibility that the Midland Purple Ware pot base also represents the remains of a similar, earlier, cache. A small cache of objects deposited for luck, to help the wall stay upright, and the land and its owner prosper.

But then again, of course, it could just be rubbish!

If you are interested in Spiritual Middens and hidden objects, there is an excellent paper here which discusses the contents and their meaning. It’s written for the general reader, so it’s not too theory heavy, and it contains links to other papers on the subject. Also, you can email me for more information, as it is a special interest of mine, and one that is only now receiving attention.

As always, comments are welcomed… even encouraged. More soon, I promise, but until then, I remain,

Your humble servant.

RH