I thought I’d venture a little farther afield this week. The blog is intended to explore Glossop’s heritage, but I feel that if I can see it from Glossop, I should be allowed to blog about it… even if it is in another county.

But don’t worry, we won’t be going to Yorkshire!

St Michael and All Angels church in Mottram dominates this end of Longdendale – it is visible from all sorts of angles, disappearing as you travel various roads and paths, only to pop up unexpectedly from behind buildings or between trees. Indeed, it’s presence keeps watch over the valley, almost as a reminder that the church watches over the people. In fact, I can see it from James’ window, on the distant brow.

It sits on a prominence called War Hill (from the Middle English Quarrelle, meaning quarry), and is a particularly bleak place, catching all the wind that roars down Longdendale from the moors. The church itself, though severely ‘improved’ during the Victorian period (read, monkeyed around with and partly rebuilt) is still at its heart essentially late medieval in date – mid 15th Century or so. Going further back, it may well have been the site of Saxon church prior to that. Travelling even further, there is evidence in the form of cropmarks that it might have been the site of a Roman signal station connected to Melandra – a perfect place with commanding views up and down Longdendale. Prior even to that, particularly given its prominent location in the landscape, it must surely have been attractive in prehistory, though there is no evidence at present.

As an interesting aside, during the late 17th Century a whole pile of my ancestors, the Williamsons, were ‘hatched, matched, and dispatched’ here (that is, they were baptised, married and buried). The Williamson family married into the Sidebottom family who were fairly big in this area, were important in the early Industrial period, and were consequently quite wealthy. Alas, my line gradually becomes poorer, and we end up in East Manchester working in a mill, rather than owning it.

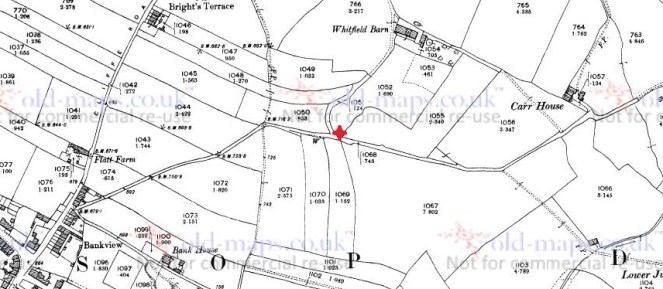

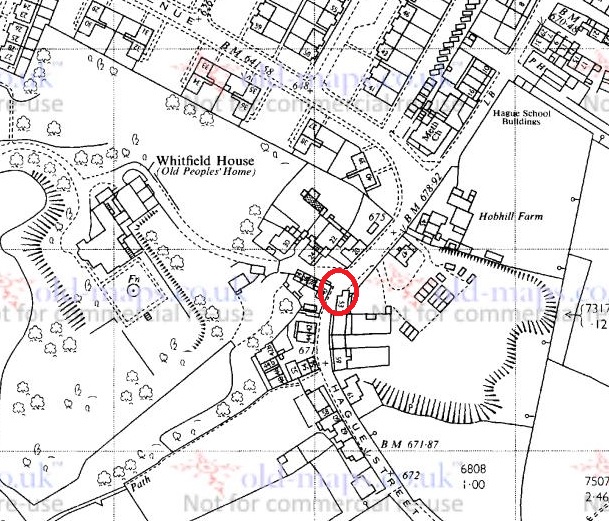

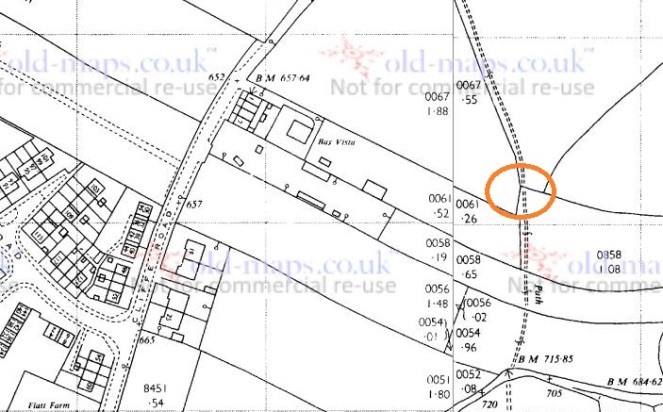

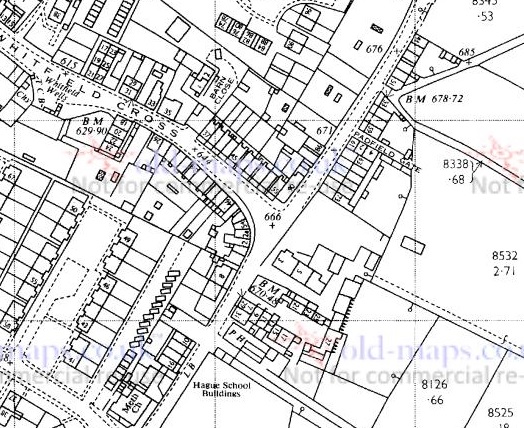

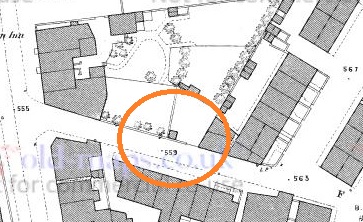

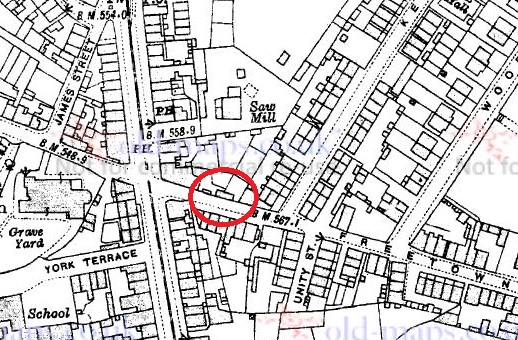

Perusing the old OS maps of the area, as I am wont to do (here), I noticed three wells in the immediate vicinity. Now, nothing unusual there, the whole area is teeming with them as we live in an area with a high number of springs. However, what was unusual is that all three, very close together, were named. Normally, a well is simply marked ‘well‘ on an OS map, but the fact that these have names could indicate that there may be more to them. And what names they are – Daniel Well, Grave Well, and Boulder Well – names that conjured up wonderful images. Well, well, well, I thought, this must be worth an investigation.

And so it was.

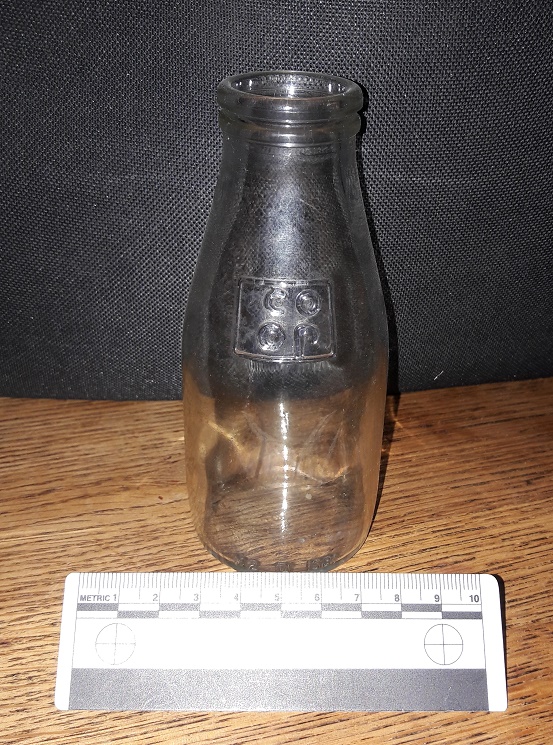

Daniel Well is situated on the left, northern, side of a track that comes from War Hill along the side of the school, and downhill to a pond. Interestingly, the only artefactual evidence from this exploration came from this first part of the track, just behind the school playground.

I am just about old enough to remember free school milk, and these are the bottles they came in… It has been over 30 years since I touched one of these last, and the feeling was one of immediate nostalgia and a weird sense of happiness. Silver foil top and a blue plastic straw… I was back in Bradshaw Hall Infants School, just like it was yesterday! What I love about this artefact is that the only way it could have ended up on the track behind the playground is if some naughty child threw it over the fence… if you put it to your ear, I swear I can hear the “vip, vip, vip” sound of Parka coats rubbing together and the cries of “go on, I dare you… chuck it!”.

On to Daniel Well, then. The sunken path is muddy, but well constructed and was clearly used – I wondered if this was the main well for the area. My first sight of it seems to confirm that thought.

The path widens out at this point, and the stone built well head structure stands well built still. The path is very boggy, and although the well is overgrown and possibly relatively dry in terms of water within it, the spring that created the well is still flowing freely downhill.

The stone-built arch that is the front of the well goes back some three feet, although it is sadly now full of collapsed rubble. To me, this seems a sad end to what was one of the most vital aspects of the village – lives were, quite literally, saved with this water. Food, drink, laundry, baths, all came from this point. People who met drawing water here married in the church above, and had children. Gossip and community, focused on this place, and yet, no longer. I would love to see it restored, or just a little better cared for.

Following the path down, the water flows into this secluded and sheltered pond.

Clearly Daniel Well was an important well in the area – the path and the stone built well head attest to this. I have no idea about the name, though – possibly from a personal name of the person who owned the land? Something Biblical, maybe? Any thoughts, anyone? The 1954 1:10,00 sees the last mention of Daniel Well on an OS map, and clearly by that point it had ceased to be important as a water source. Sadly, I doubt anyone living nearby would know it was there now, or at least know that it had a name.

Making my way back up, I decided to look for the other two wells. I had studied Google maps before exploring, and took a while to work out the locations by superimposing the old map field boundaries onto the modern satellite image of the area.

Alas, there is nothing left of Grave Well except a muddy patch in the field.

I am not sure what would have stood here originally – perhaps a structure like that at Daniel Well, but I feel this is unlikely: it is in the middle of the field, and with only a minor footpath to get to the well. No, I think it more likely that it was a simple affair that held some water where it bubbled from the spring underneath. I love the name, though – obviously derived from its proximity to the burial ground of the church, out of view to the right in the photograph. Either that, or it may recall the discovery of a burial in the immediate area. Either way, it does raise interesting questions about water tables and burials, though, and I’m not sure I would like to drink from Grave Well! Its last mention before it disappears into the veil of history is on the 1882 1:10,000 OS map. It clearly lost its importance, and was gradually forgotten about.

Pushing further on I looked for the Boulder Well and, when I found it, was similarly a little disappointed… at least at first, anyway. It was another muddy patch.

As with Grave Well, I am not sure what would have stood here originally – probably nothing much. Also, in common with Grave Well, the last mention of it on the OS map is the 1882 1:10,000 map, after which it disappears, and is gone forever. The name intrigued me, though: Boulder Well is a very specific name, deriving from… well, one assumes… a boulder. The lack of boulder is, then, confusing, and a little disappointing.

I pushed on regardless, to see what I could see. And lo! In the next field north, at the edge, there stood a bloody big boulder!

Now, although it is in a different field, this must be the origin of the name Boulder Well. Indeed, it appears to have been moved ‘recently’ – it is sitting on top of the grass, rather than embedded in it. However, if it had been moved, this at least would explain why it is in a different field from the ‘well’, and why it now stands comfortably out of the way at the field boundary. I wonder when it was moved, and where it stood originally.

The fate of these wells is interesting, and is obviously tied to the introduction of clean piped drinking water directly into your home. We – and I am very guilty of this – have a tendency to romanticise the past, and a wish to remove the trappings of modern day living, to peel back all the ‘progress’ we have made, and to revert to a simpler way of life. I love the idea of having to walk to a well to draw pure cold water, it would be so… earthy, grounding, basic. Free and simple.

But then I have never done it in the rain, sleet, or snow, wearing ill fitting wooden clogs, wrapped in a basic cloth shirt, slipping down a muddy unmetalled path, after having worked 15 hours in a mill.

I may yearn for a less commercial, more simple life… but I don’t yearn for pneumonia.

Hope you enjoyed the jaunt around Mottram. I have a few more posts I’d like to do about various wells – they intrigue me – so watch this space.

As always, comments of any kind are most welcome.

RH