*Ok, so I couldn’t think of a better title.

What ho, what ho, what ho!

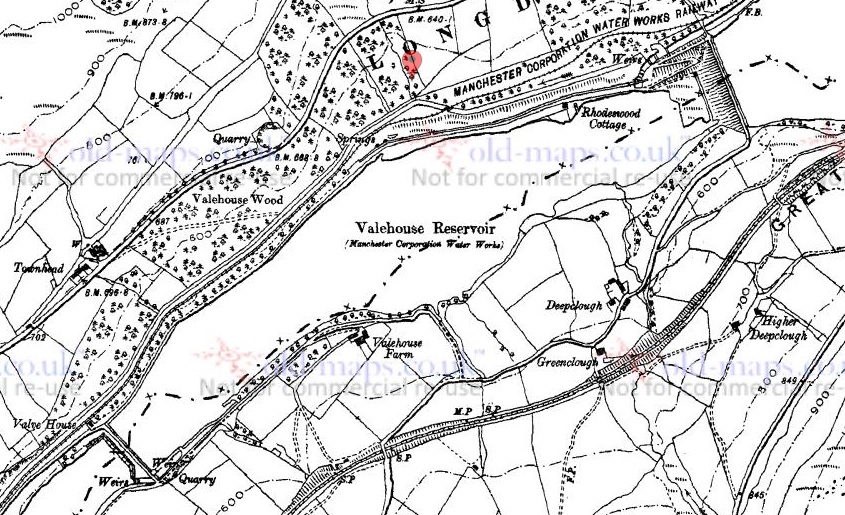

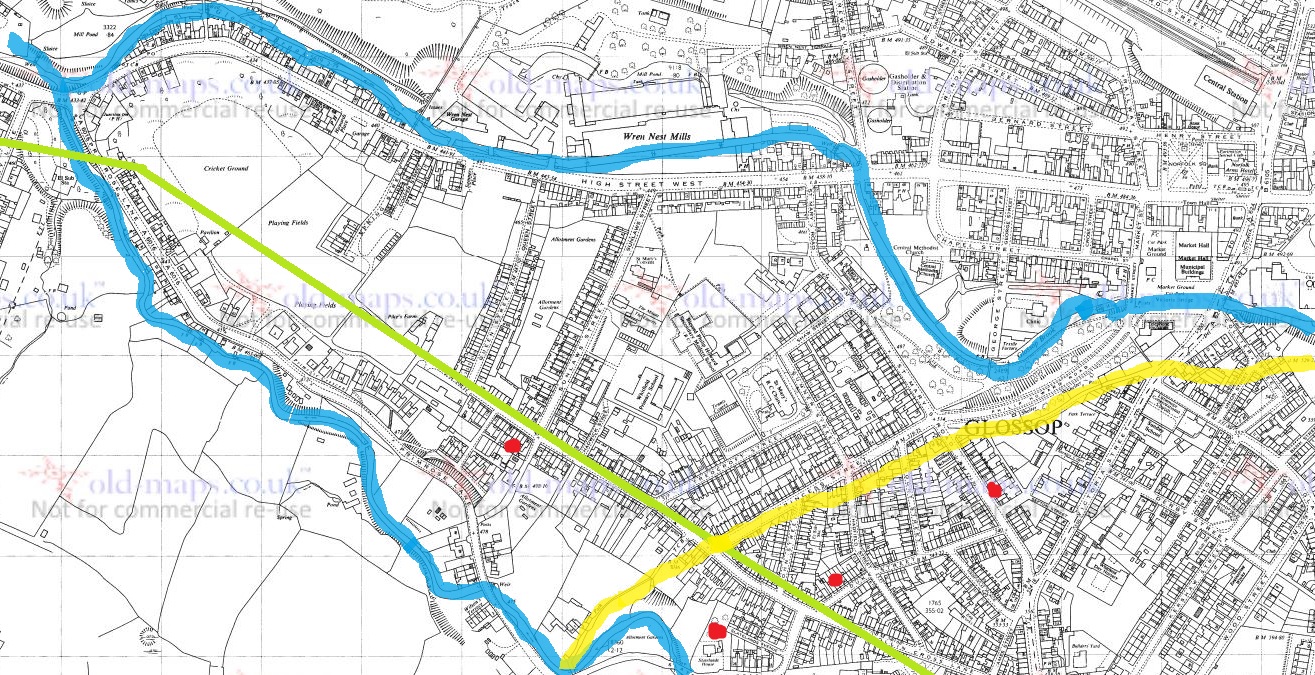

So, right now, as we hurtle toward the solstice, is my favourite time of the year. Spring into summer – the days are long, my birthday is hoving into view (19th July, if anyone is interested… and a dark fruity red, if anyone is feeling flush). It also means time spent in the garden, planting and preparing the soil. Hamnett Towers is blessed with a small back garden (utterly destroyed by chickens… honestly, it looks like the Western Front), and a slightly larger front garden where the vegetables are planted. Both of these forces of nature – chicken and man – excavate all sorts of goodies. Predictably, I have kept everything I have found, and kept them separate; Hamnett Towers was at one point two separate ‘back-to-back’ terraced houses, so the archaeology of either side might tell a slightly different story (old archaeological habit). And so far, this year has produced some very interesting bits.

So, please join me in the garden. Ah, sorry, no shorts or baseball caps please – this is an English gentleman’s abode; t-shirts I can just about cope with, but I mean, a chap has to have standards dash it!

Here’s the day’s findings from the front garden:

Let’s start with the nail – a Victorian, hand-made, copper roof nail, to be precise. I’m something of a magnet for these things, and they seem to find me wherever I go. They are truly mundane – the nail that holds on a roof tile – and yet are such lovely and tactile things (I’ve blogged about them before – here – FIVE years ago… blimey!). Copper was used as it is largely resistant to corrosion, and their square section is a dead giveaway of age.

They are made relatively simply, but by hand. Each nail is cut via a press from a long flattened strip of copper (thus the square body of the nail). It is then placed into a small mold or former, point down, and the exposed top is hammered by hand until it flattens out, forming the nail head. Close-up you can see the two flashing strips formed as the soft copper is driven between the halves of the mold.

The nail may have come from my house roof, which is a great thought.

Next to the nail is a sherd of spongeware, probably from a large bowl or shallow dish. I find a lot of this particular vessel in the garden, and I might have to try and reconstruct it sometime (follow the link above, 3rd photograph down, on the right for more of the same bowl).

Next row, a sherd of marmalade/preserve jar (here, for more information), and then two thoroughly uninspiring sherds of white glazed pottery. Then, this beauty!

Wonderful! A small bone button, and almost certainly Victorian in date. Delicate, handmade, and slightly off-centre, it is lovely. Again, something so mundane – every item of clothing would have had a dozen of these; will people be cooing over the zips in our trousers in 100 years? And yet, here we are, admiring it’s beauty. Bone was such a common substance in the pre-20th century, and we tend to shy away from it as a material now – how many of us would brush our teeth with a bone toothbrush? Or use bone game pieces? I think we have become a little squeamish. Yet, it was a major resource in history – so many animals, so much bone. Bone preserves very well in the right conditions, and although this has cracked with age, I bet it could be sewn on and used again.

Right then, the image of the Somme, c.1916, that is the back garden. There’s always something that turns up here, not all of it interesting, but usually worth a look. And this year is no exception, with a couple of very nice finds.

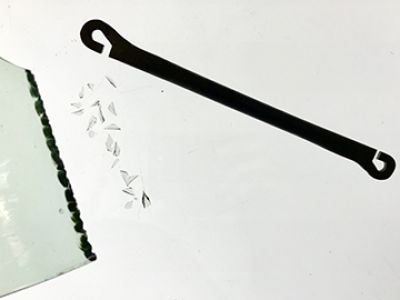

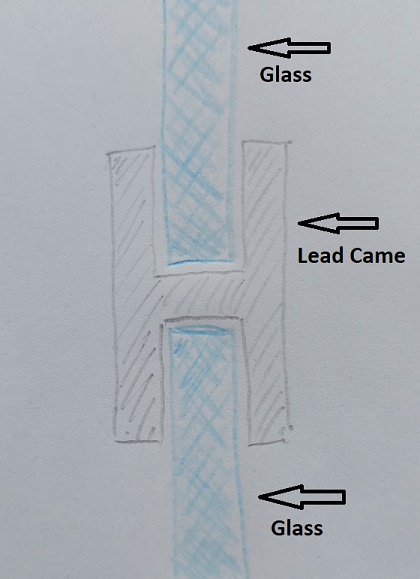

So then… top left we have bonfire glass. Essentially glass that has been melted in a fire. This may have been accidental, or just the result of rubbish disposal. Often Victorian and later rubbish dumps were set on fire to keep the rat population down, and bonfire glass can be quite pretty. This one… not so much.

Ignore the next sherd for the moment, and move onto the cream coloured stoneware sherd, possibly from a flask or other oval shaped vessel. Then we have some glass – it is quite chunky, which indicates it is old, but isn’t that lovely green colour, nor full of bubbles, that would indicate a Victorian date. Probably Early 20th century, and likely from a small bottle – perhaps medicine or similar.

Ignoring the other reddish coloured sherds, again for the moment, we have this beauty:

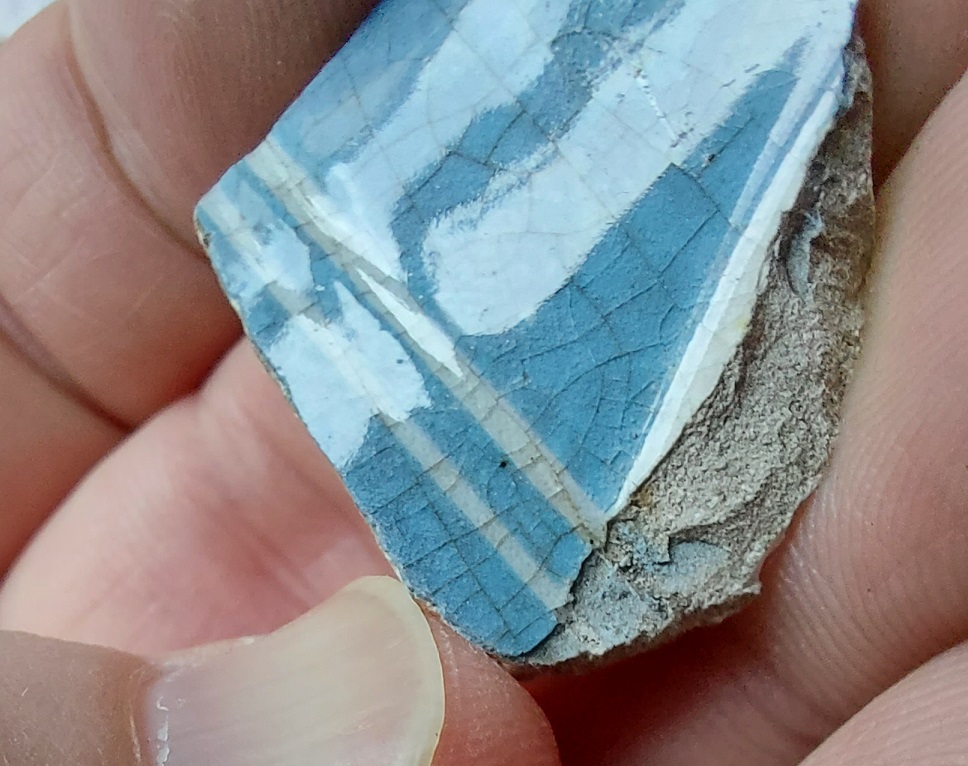

This is often called Pancheon Ware, after the large (50cm+) pancheon bowls that were extremely common from the 17th century to the early Victorian period. The correct term should be Post Medieval Redware, but that covers a multitude of pottery types and shapes from c.1550s to the Victorian period, of which this is just one.

They often occur in huge chunks up to 2cm thick, and are usually glazed only on the interior to make it waterproof. I’ve talked about them before, but this is a nice example, showing the red slip on the surface, and then the dark brown glaze, made by adding iron oxide to a lead glaze, producing the deep shiny colour. The glaze on this, as with many, has been allowed to slop over the side and stop just below the rim, producing a messy natural decoration (the example above shows the glaze stopping on the rim, but you can see the effect they are going for).

Below and right of this sherd there are 4 sherds of standard Victorian to mid 20th century whitewares nothing inspiring, or even particularly worth writing about, although there is a rim of a bone china cup. Below and left is a single fragment of a clay pipe stem. Again, nothing exciting – the hole, or bore, through the middle of the stem is narrow which tells us that it is Victorian in date (broadly, a wide bore = 17th to early 18th century, a narrow bore = late 18th to 19th century). Still, it’s a bit of social history… I just wish I could find a bowl!

Then there was the treasure! Occasionally, certainly not often, I find something made of metal. And a few weeks ago, as those who follow me on twitter will know, I found a metal button.

Well, no… credit where credit’s due – I didn’t find it, Master Hamnett did, with his six year old eagle eyes. A lovely little 2 eye brass button, probably Victorian in date. It’s probably from a child’s dress, probably something like this:

And if you look closely using a decent magnifying glass, rather than the dodgy macro setting on my phone, you can see the remains of the original cloth that would have covered it:

It would have looked like this when new:

The thing I love about this is that the child must have lived and grown up exactly where Master Hamnett is now, and doing many of the same things. There is real sense of connection to the past through a single, small and dirty, seemingly uninspiring object. By the way, the story of the Victorian child’s dress (one of several, I hasten to add) is for another time, but it is from a probable apotropaic cache that was donated to me for safekeeping. One of two I now curate. I really don’t have enough time to write all this up, so if someone want to donate a stack of cash to allow me to write, please feel free!

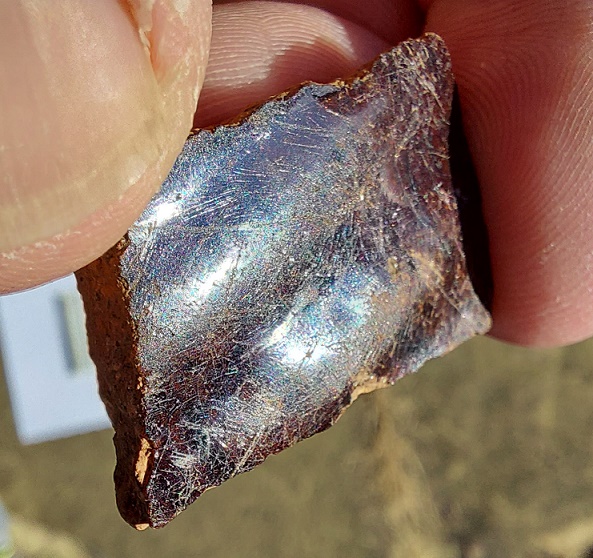

And now this, the real treasure. Quite literally, for once.

I know at first glance it looks like something has blown it up, but look beyond that, and it’s a wonderful, if completely knackered, piece Victorian costume jewellery brooch. It’s missing just about everything, including the central glass stone, but would have been very pretty – probably looking something like this:

I didn’t know what it was when I picked it up, but it was that greyish green that indicated a copper alloy (brass or bronze, for example), and is something I always pick up. It was only when cleaning it that I noticed the paste stones.

Amazing, really. And this was just a small amount of time poking around, getting really close and personal with the soil in my garden. And my garden is not unique by any stretch, not even close. I guarantee, every garden in Glossop – no, the country – will produce some treasure – whether it’s early Victorian annular ware from a house near the station, a broken bottle rim from a former pub, a pipe stem from a current pub, or a piece of Victorian child’s plate from a modern garden in Simmondley (all examples from experience). Obviously, I realise that not everyone is lucky enough to have a garden, but we all can access some green space. As an experiment, this evening, pour yourself a drop of the stuff that cheers, and go and sit on what ever patch of earth is closest to you. This may be your garden, or it might be a park, or someone else’s garden, a playing field, or public footpath, or whatever. Now sit down and take a deep breath, listen to the sounds – birds or traffic – tune in, and simply look around you. If you can, dig about a bit, and don’t be frightened of getting your hands dirty, either. With enough time, something will turn up. And please, mail me the results.

Right, that’s about it I think. Next time more pottery – essentially a part 2 to this post, looking at the pottery I told you to ignore above. A competition! If you can get back to me and tell me what they are, and why they are not our type of thing, before I can post the next article, you can win those bits of pottery. Woohoo! (Now look here, Mr Shouty… some people like pottery, you know. And no, I’m not “having a laugh“).

More very soon, but until then, look after yourselves and each other.

And I remain, your humble servant,

RH