What ho! wonderful people. In case you hadn’t worked it out by the title, today’s blog post is all about pipes. I may have mentioned previously that I absolutely love clay pipes – there is just something so tactile and personal about them. And yet as an object they were disposable; I have referred to them as the cigarette butt of the Victorian period, as often they were bought pre-filled with tobacco, smoked, and then thrown away. I have previously posted a few good pipe fragments (here for example), but I have others…

This is no place for a general history of tobacco smoking, but it is worth mentioning that it was only 1580-ish that the first ships came back from the New World with the dried leaves as cargo. This provides us a nice terminus post quem (archaeology speak for the earliest possible date something could have happened) for clay pipes. Interestingly, we also have a terminus ante quem (archaeology speak for the latest date something could have happened) – the cigarette became very popular late in the reign of Victoria, gradually replacing the pipe, and it is generally taken that the use of clay pipes died out after about 1900. Obviously, this is not a hard and fast rule as people still smoked them (see one of the pipes below, for example) – and indeed you can still buy clay pipes – but it is a useful rule of thumb. So then, for a period of roughly 300 years, between 1600 and 1900, people were smoking these things. But the thing with clay pipes is that they are ridiculously breakable, which is good for us. Bowls are found rarely, and even more rarely complete, but the stems, looking like white cigarette butts, are very commonly found, and people amass huge numbers of them, even making them into jewellery.

If you interested in any way in clay pipes, then the National Pipe Archive website is for you – a goldmine of accessible factual information, and their ‘how to’ section covers everything from excavating and cleaning to dating and drawing. There is also a huge reference collection of books and articles on excavated pipes. I have lifted some of their images for illustrative purposes and make no claim to them – but please have a look.

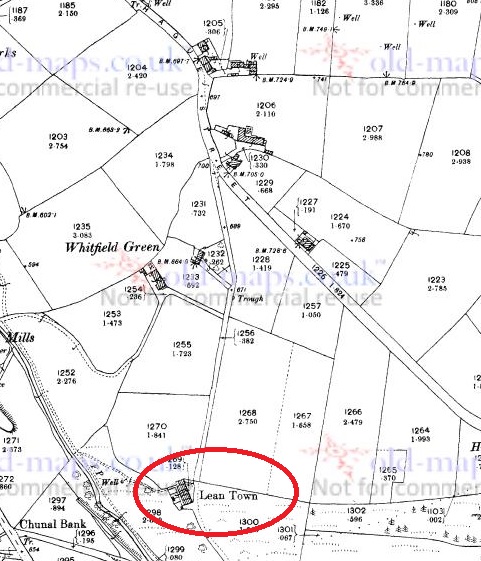

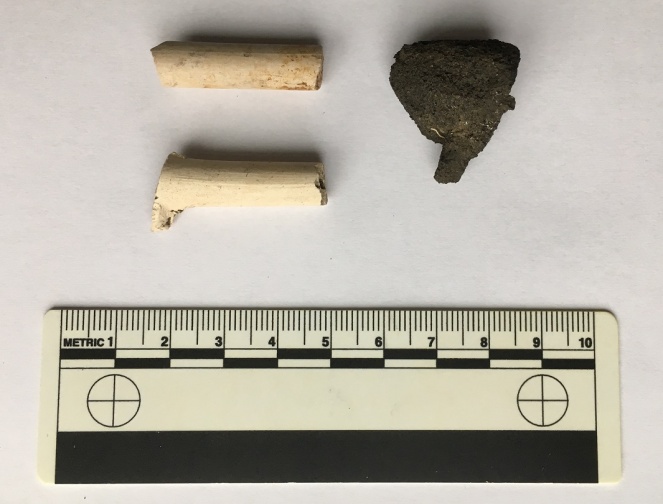

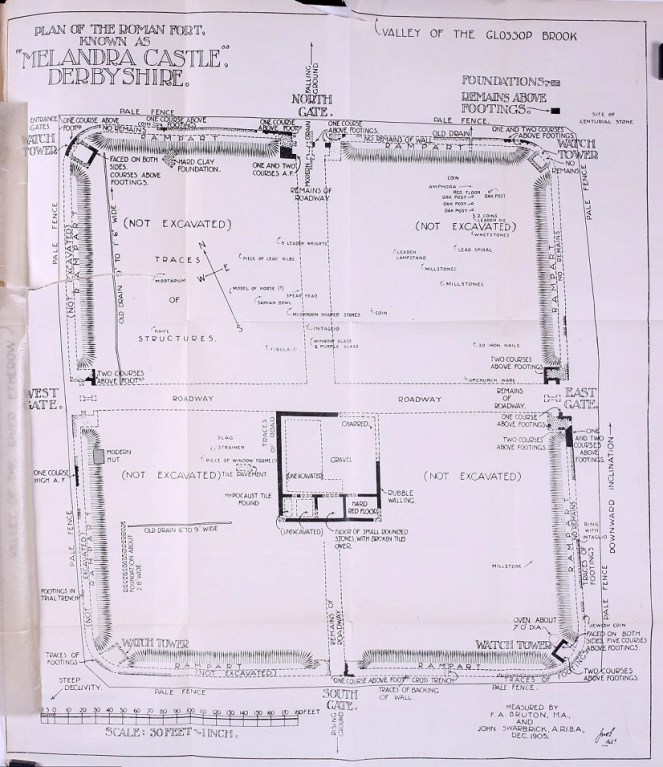

Here is the anatomy of a pipe :

![pipes[2]](https://glossopcuriosities.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/pipes2.jpg?w=663)

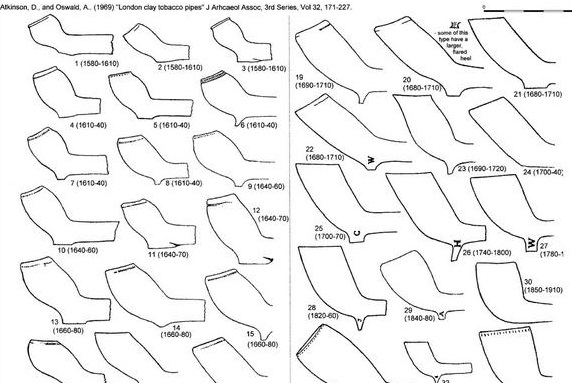

They were mass produced in huge quantities using a white ‘pipe clay’ formed in a mould, and then kiln fired. In terms of date, they are quite difficult to pin down precisely without lots of detailed information. The rule of thumb though is that the smaller the bowl, the earlier the pipe – tobacco was very expensive in the 16th and early 17th century, but became much cheaper later on, leading to larger bowls, and a more wide appeal. There is also some chronological variation in the stems too – the earlier pipes had thicker stems and the bore (the hole down the middle of the stem) was wider too. And there are also very subtle changes in shape of the bowl, the stem, the heel, and the tip, that allow rough dates to be given to the pipes, but these too are very broad. A huge amount of work has been done on dating pipes, but the reality is that it is not hard and fast, and unless you have a manufacturers name or mark, or it comes from a secure archaeological context, pipe dating is in half centuries and decades, rather than specific years.

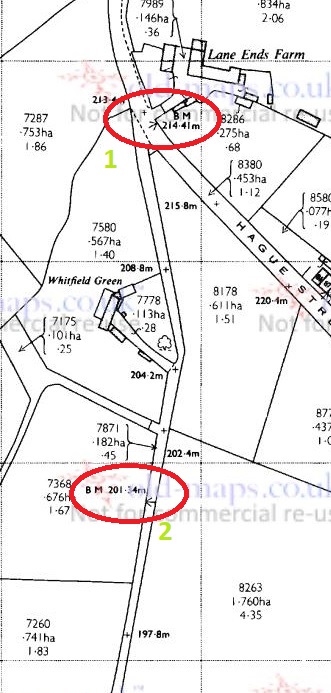

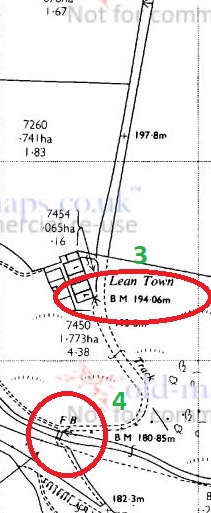

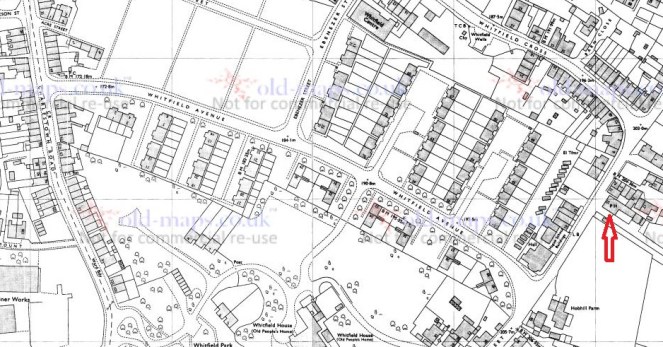

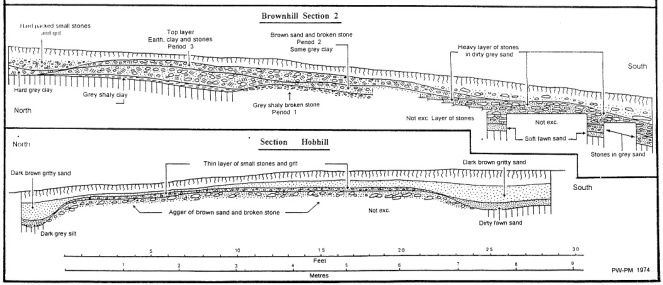

Here are some images showing dates for various pipe styles. It is worth remembering that each area has its own industry making these things, and thus what might apply in London, will probably not apply in Manchester, although the broader trends are applicable, and pipemakers did copy each other’s designs.

![pipes[1]](https://glossopcuriosities.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/pipes1.jpg?w=663)

So then, the pipes.

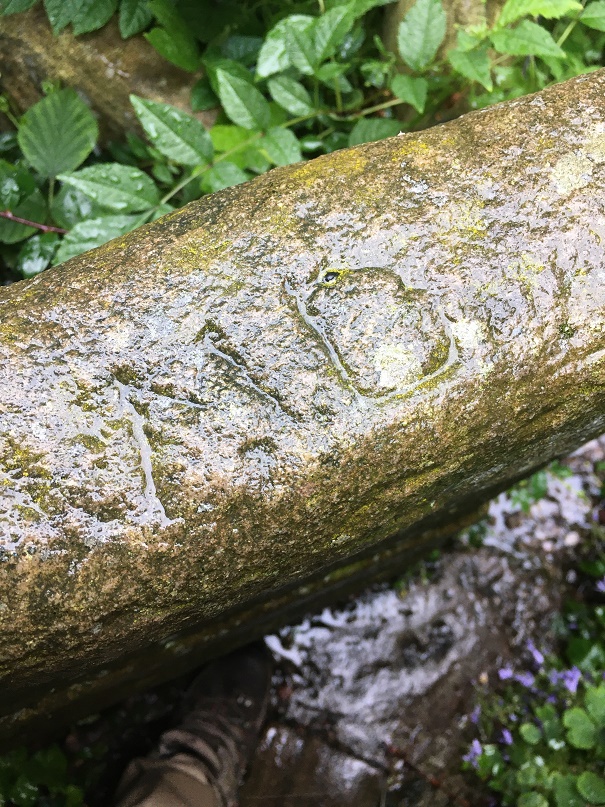

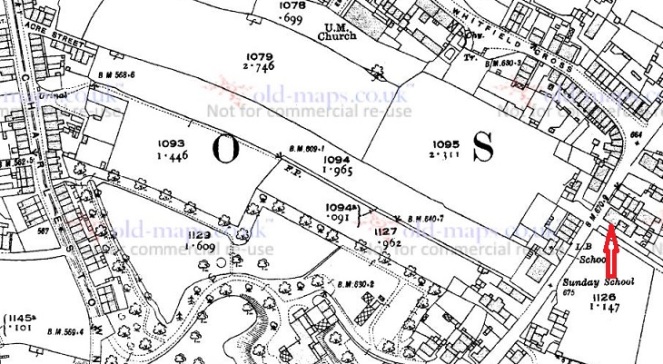

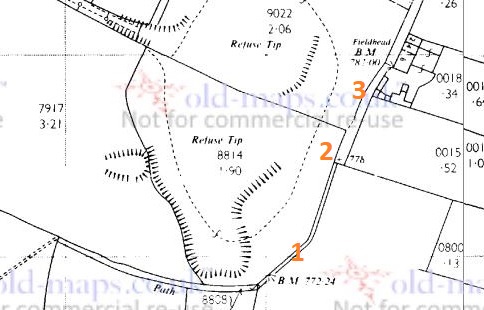

This first one is something of a rarity in that we can say a bit about it, and it has a date. It was found with some late 17th and 18th century pottery near Crowden, and thus I assumed it was of a similar date.

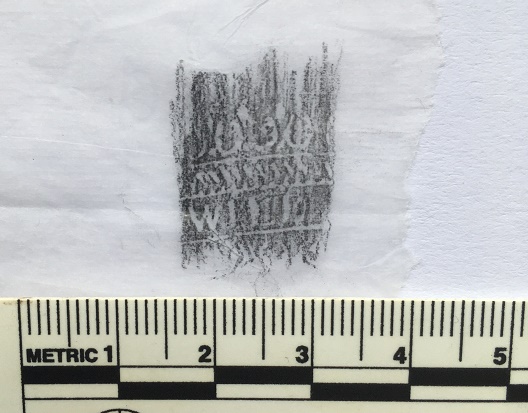

It was only when I cleaned it that I realised that it had a rolled stamp around it which at first I thought was simply decoration. It was only after I had taken a rubbing that I saw the name ‘WILD’ printed. Fantastic!

Even more amazing, after only a few moments rummaging around some files, I found a perfect match to this stem from an excavation in Sheffield. This truly never happens! It was made by Thomas Wild, a pipemaker working in Rotherham between 1750 and 1790 – which is absolutely spot on for the date of the pottery.

The published version of mine is is in the Clay Pipe report by S.D. White (2015) to be found here (No.13 in the catalogue). The location of Crowden on the Woodhead Pass means it would have had easy access to the market at Rotherham, and thus the pipes. Honestly, it’s not often that you can make a connection like that – the place of consumption to the place of production, and all along a single road. It’s even been made in the same mould. It’s things like this that keep me alive in archaeology, and makes it all worthwhile.

I found a few other fragments in the area of this pipe but nothing as spectacular as the stem, alas, although the bowl sherd on the bottom left is quite nicely decorated, and dates to the same period.

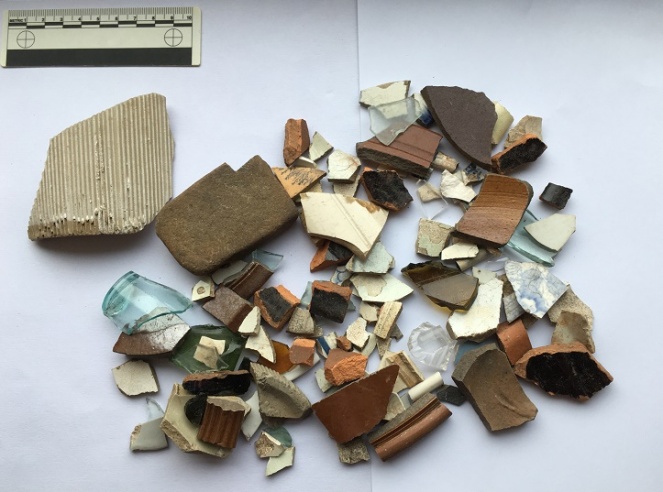

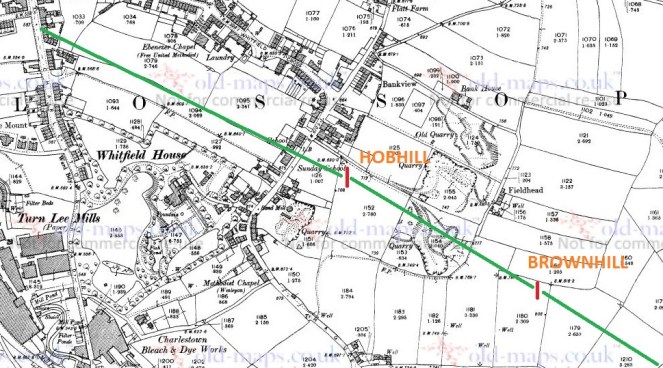

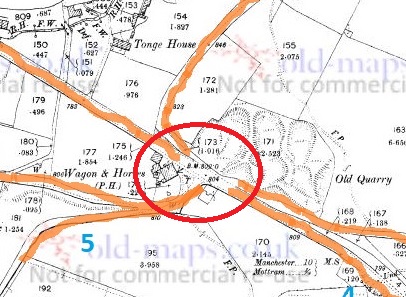

The next one is also a great find. From a Victorian dump near Hadfield, it just plopped out of the earth soil right in front of me.

It is almost complete – missing just a part of the bowl – and looks as though it had never been smoked before it was presumably dropped and broken. It is an interesting shape in that it has a short stem, which means it was made for a manual worker of some form. The last thing you want if you are wheeling a barrow around or swinging a pickaxe is a long stem that would get caught and break. Manual workers would normally break off the stem to create what were called, for obvious reasons, ‘nose warmers’. Manufacturers caught on, and they made short stem pipes for such a market. This one, helpfully, has the manufacturer’s name on the side: Samuel McLardy of Manchester.

I was going to give you a history of McLardy as a pipe maker, but this blog run by a pipe expert has done an amazing job already (it’s well worth a look). Briefly, then, McLardy was born in Glasgow in 1842, and set up his company in Manchester in 1865 in Miller Street, and then later in Shudehill. By 1895 the company was making over 5 million pipes per year, which is astounding, but in keeping with clay pipes in general, sales dropped, and the company was ended in 1930. There is a sales catalogue from the 1920’s in the above blog, in which the above pipe is listed as #392 (page 1). This provides us with a good date for the pipe – roughly 1920, or possibly a little earlier – very late in the history of clay pipes, which is interesting.

Also from the same dump, was this lovely, if battered, bowl.

Large, so late in date (1860-80 ish) it is marked with a crown above the letter ‘L’. A little bit of online research produced this article, which details the ‘Crowned L’ as a trademark of superior Gouda pipemakers of the 17th and 18th centuries. However, by the 19th century, English and Irish pipemakers were freely using the ‘Crowned L’ as a way of claiming that their pipes were of a similar standard, so the trademark became debased, and these pipes are very common. Incidentally, what on earth did we do before the internet? This sort of research would have taken weeks, months even; it took me less that 30 seconds – longer, in fact, to write this. Incredible.

I’ll end on an excellent, although sadly not complete, Victorian pipe. In the spirit of truthfulness, I should admit I found it on a Victorian tip in Lancashire, nowhere near Glossop, but it’s such a wonderfully ugly thing that it deserves its moment of fame.

It is an eagle’s claw holding an egg. Of course it is… what else would you want to see whilst you were puffing away on your pipe – the Victorian equivalent of heavy metal fashion. It is missing two talons, but still quite remarkable. Apparently the Victorians were really into their novelty pipes – football being a particular favourite subject.

I know I keep saying it, but I love clay pipes.

Right, that’s your lot for now. Please send me your pictures or comments about pipes, or indeed about anything vaguely historical/archaeological… all comments are welcome.

But for now look after yourselves and each other, and until next time, I remain.

Your humble servant,

RH