Evening all

It suddenly occurred to me that I hadn’t published any pottery or other bits and pieces for a while. Of course, whilst I may not have written anything, it doesn’t mean that I have stopped picking things up… nope, I have literal bags of the stuff, much to Mrs Hamnett’s annoyance.

So here goes with some interesting bits and pieces from all over Glossop.

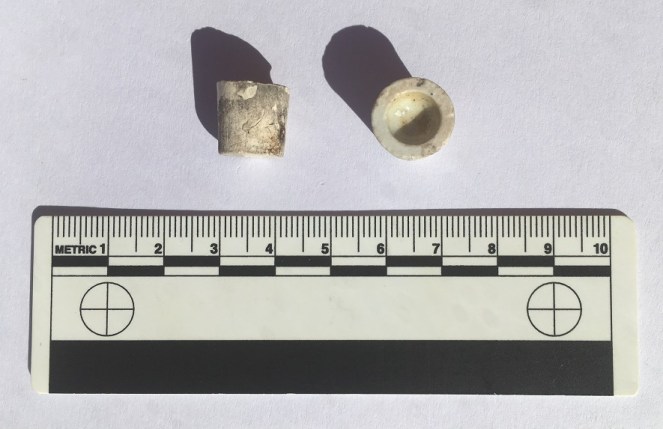

These first sherds of pottery are from the back garden of the Prince of Wales pub, Milltown, Glossop. I have already blogged about the clay pipes from here in this post, but this is the pottery that goes with them.

The same age, unsurprisingly, Mid to late Victorian, possibly early 20th Century. The stoneware (top right) is fairly bog standard, and probably comes from a ginger beer bottle or similar (which makes sense, given where we are). The blue on white pottery is difficult to date from small fragments, but it starts in the 1790’s, and carries on until… well, now! This wouldn’t be early stuff, and it’s been kicking around for a while in the soil, so Mid – Late Victorian it is. The top left is from a featheredge decorated dinner plate, measuring 24cm in circumference. Here is a good example of the type with some discussion. This style of pottery also starts 1790ish, but the type we see here is the same date as the others. It is commonly found with a ‘shell edge’, but this one has the impressions on the surface, but not the undulations. All very common, and very in keeping with the place being a pub in the busy Milltown area. I want to know what was being served on the plate – good hearty pub food of meat and veg, one assumes.

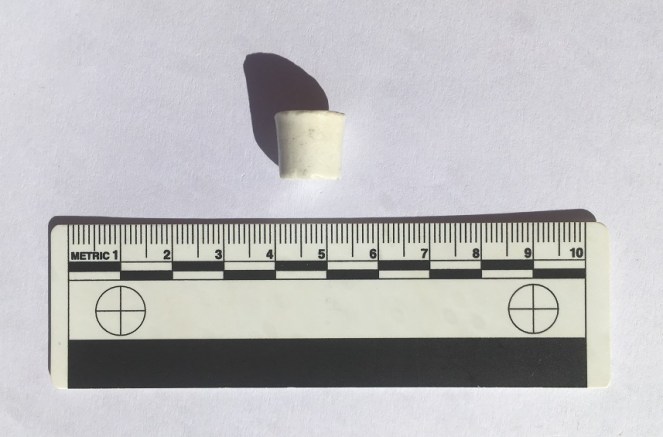

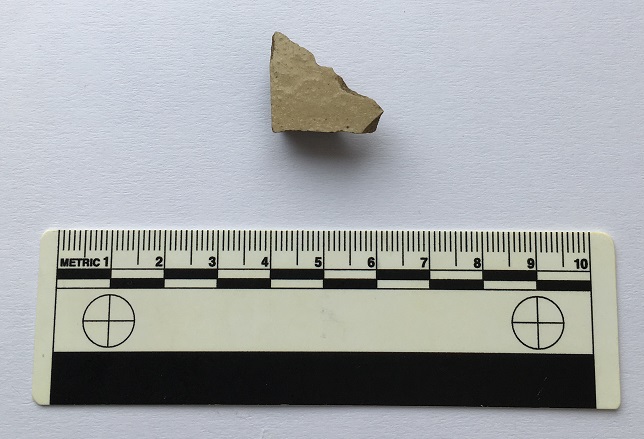

This next sherd is from Whitfield Recreation Ground. I found it a few years ago, after some heavy rain, just underneath the bench by the swings.

Cream coloured stone ware, hard fired, and virtually indestructible, as I have mentioned elsewhere. This sherd is glazed inside and out, and comes from the bit that the joins the base to the side. This type of pottery was only normally used for ginger beer or milk in the late 19th and very early 20th Centuries, so we may assume that as the date. It’s a possible rare survival from a time before the recreation Ground was there (it opened in January 1903). I intend to do a future blog post about the ground, as it has a fascinating history.

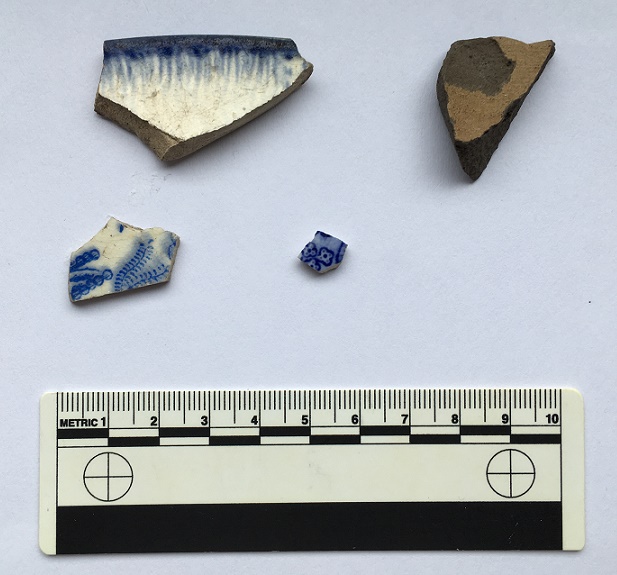

This next lot is from Old Lane in Simmondley. This was the original road between Charlesworth and Glossop, and joined in the meeting of several roads at St James’s church, Whitfield (I have blogged about that meeting place before). I did a bit of a walk along the path as far as it goes (here, on my Twitter feed – and the next few photographs on from it), and it eventually fizzles out into fields. But along the way I picked up a few sherds.

Top right is three sherds of cream ware, without decoration, and eminently undatable – probably Victorian, but ultimately these are destined for the midden in my garden. Top middle is a piece of thick slip glazed earthenware. This, I think, is 18th Century, so relatively early, and certainly earlier than the other sherds. It is glazed on the interior surface only, with the outer surface being washed with a red slip, so I think it is probably a cooking pot of some sort. Top left is a large stoneware storage jar of some form, or possibly a flagon like this. It is salt glazed on the inside, measures 14cm in diameter, has a chamfered edge around the base, and is almost certainly mid to late Victorian. Bottom right is a fine china open vessel – a saucer possibly – it is undecorated, and not enough remains to get a diameter. Bottom left is a broken fragment of a stoneware storage jar. It is salt glazed, and has an impressed decoration of a border of round blobs, which is a very common motif for this type of pottery.

Now, the good stuff!

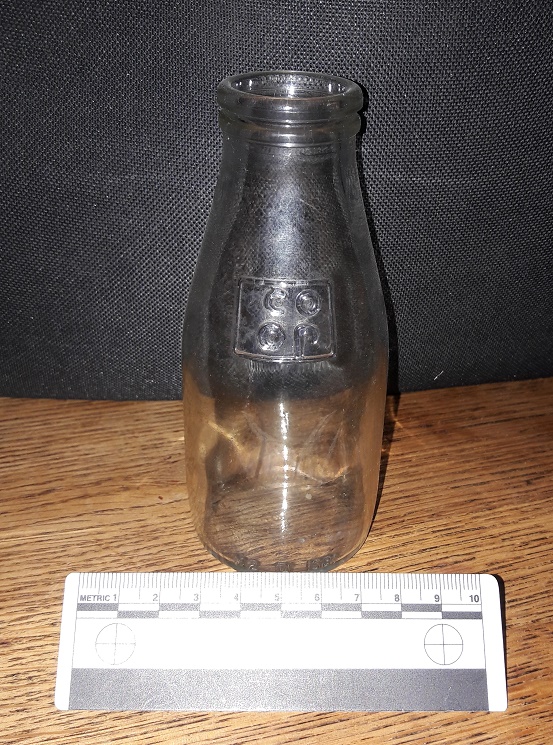

There is a place, if you know where to look, in Manor Park, that produces all sorts of goodies. I think it is a late Victorian – Edwardian rubbish dump, or at least was one before being redeposited. Over the last few years, I have pulled some very interesting bits and pieces out of the soil, and I suspect there is plenty more, too.

First up, these two.

The one on the right probably contained a hair oil or something (I don’t known why I know that, or even if it’s true, but I seem to recall reading it somewhere). Not that impressive, other than the fact that it still has the original label on it… except I can’t read the bloody thing! Frustrating.

The blue one on the left is lovely, though. Not a mark on it, and when I cleaned it off, I realised two things – firstly, there was a thick liquid inside it, and secondly, the seal was still good. I cleaned it really well, and gently opened up the bottle, and despite Mrs Hamnett daring me to taste it, I instead smelled it – faintly floral and clean. I think it’s rose scented oil for ladies to wear. A wonderful find.

The next two are really quite nice, too.

On the left, a fragment of a child’s cup, presumably with a nursery rhyme round it. I have looked up the phrases “a terrible grin” and “blew them both”, but nothing pops up the internet. If anyone has an idea, please let me know, as I’d love to find out. The fat figure also seems to have a tail – a dog or wolf? I was thinking the Three Pigs as a possibility, with the wolf blowing down the houses, but I don’t remember him blowing two houses down…

On the right, one of my favourite finds. A hollow-cast toy soldier, a child’s prized possession, perhaps. A member of the Grenadier Guards, he has his rifle shouldered, and is marching, albeit with no feet, but at least he has the dignity of having paint. I love toy soldiers, and my own childhood was filled with Airfix plastic ones (I still have them… they await Master Hamnett’s sticky claws!). They were cheaply produced in their thousands, and are not uncommon in rubbish dumps, but I absolutely adore this figure. I have looked online, and although there are thousands like him, I can’t quite place him.

Amazing stuff, and if you buy me a drink, I’ll tell you where to look!

And to end with, a little foreign fun. During my France trip this summer, I found this crumbling out of a soil bank in a vineyard, on the road to the walled city of Carcassonne.

It’s the dimple from the bottom of a wine bottle – technically called a ‘punt’. This one is blown glass, which ages it – you can make out the tiny air bubbles when you hold it up to the light. I’m no expert, but I would say it is certainly 19th Century – and apparently the deeper the punt, the earlier the bottle – so perhaps earlier? Anyway, given where we were, I couldn’t very well leave it there, could I?

Hope you have enjoyed the pottery, and as always comments and questions are most welcome.

Your humble servant,

RH