What Ho! And a happy New Whatsit to you all, yes, even you Mr Shouty-Outy, even you.

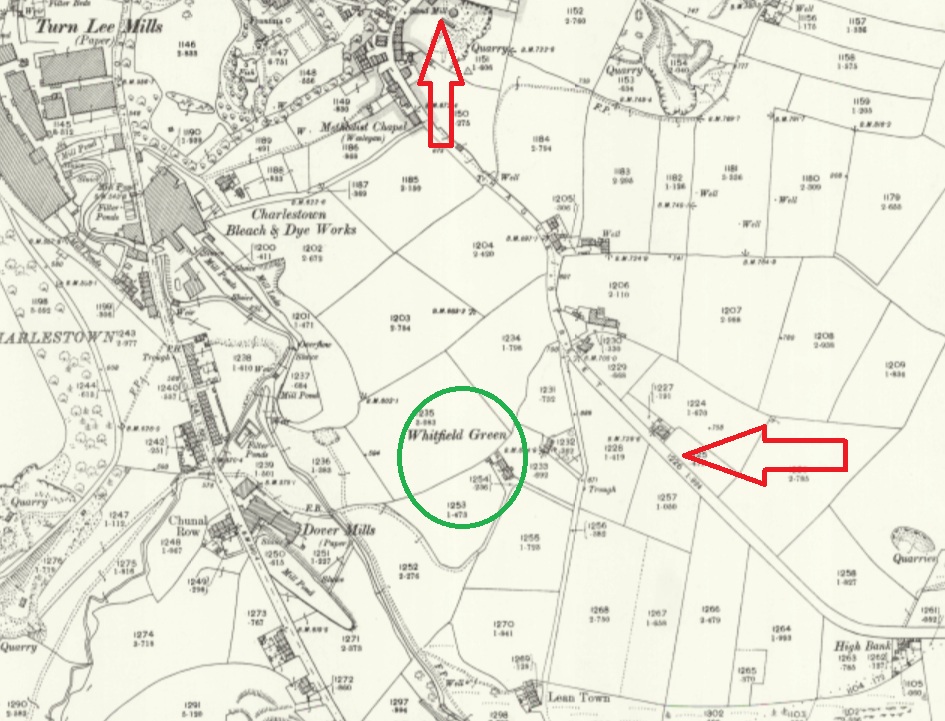

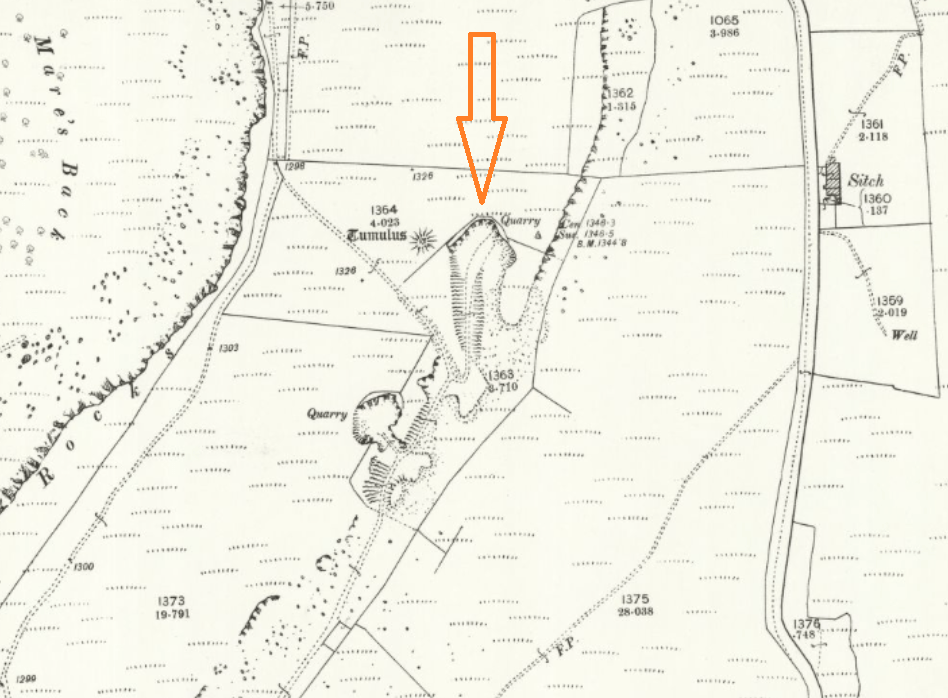

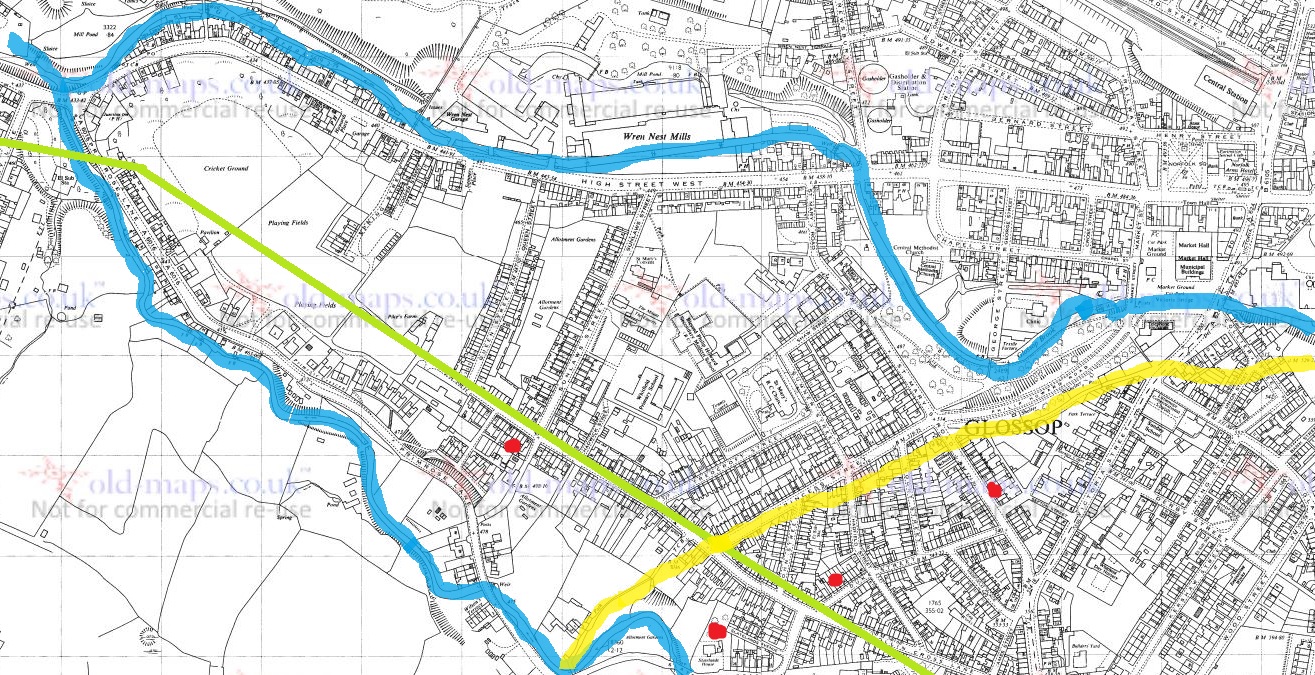

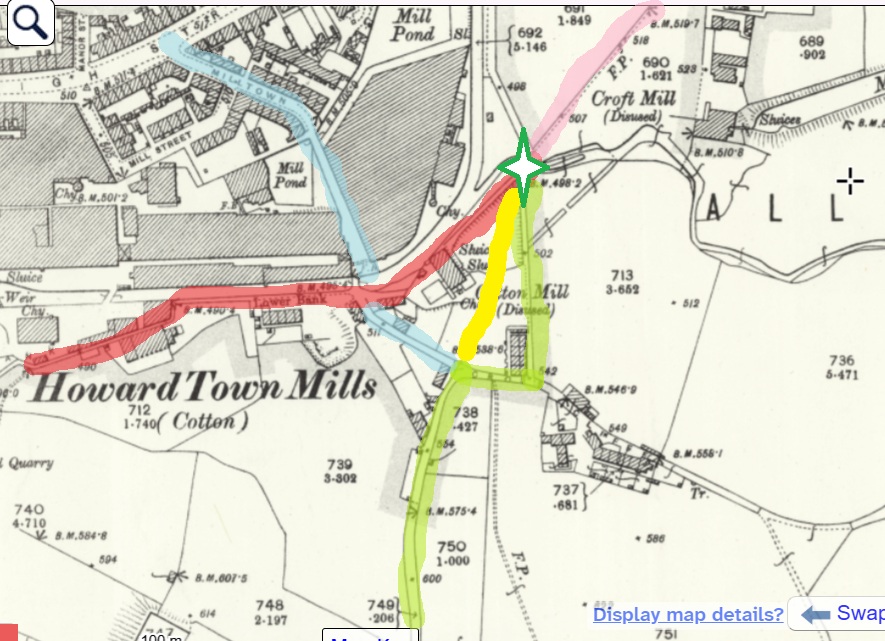

So, I was wondering down Cliffe Road in Whitfield the other day – actually on my way to Lidl, since you ask, and yes, to buy a bottle or two of the stuff that cheers… amongst other things (mainly cheese, if I’m honest). The road dives steeply down, and then takes a left turn at the bottom, and leads past the new build houses on the old Velocrepe site and onto Milltown. Now, I’ve always found this stretch of road very interesting. The main road from Chapel en le Frith to Glossop (and beyond), and thus Anglo-Saxon in date, it originally seems to have carried on straight, where it joined The Bank – the medieval/Post-Medieval track coming from Simmondley to Glossop – and together crossed Shelf Brook via the foot and road bridge at the entrance to Shirebrook, but was presumably then a ford or basic bridge. The route of this track was altered when a mill was built here, probably in the 1780’s (dates are a little fuzzy), and a mill pond put where it once ran. The newer route was/is to the right, and then down, past some mid 19th century houses there. Here, this carefully and skilfully annotated map explains it better visually than I can with words:

But here I am again, getting distracted! This post is not about the tracks… well not as such. But rather, what such tracks were made from. The earliest tracks were simply mud, and were impassable in the rain, or with winter blowing cold, and Glossop was notorious for its frankly crap roads, which would have been patched and ‘surfaced’ with rough stones as and when it was needed, the remains of which can be seen occasionally be encountered peeking through the tracks where it has been worn.

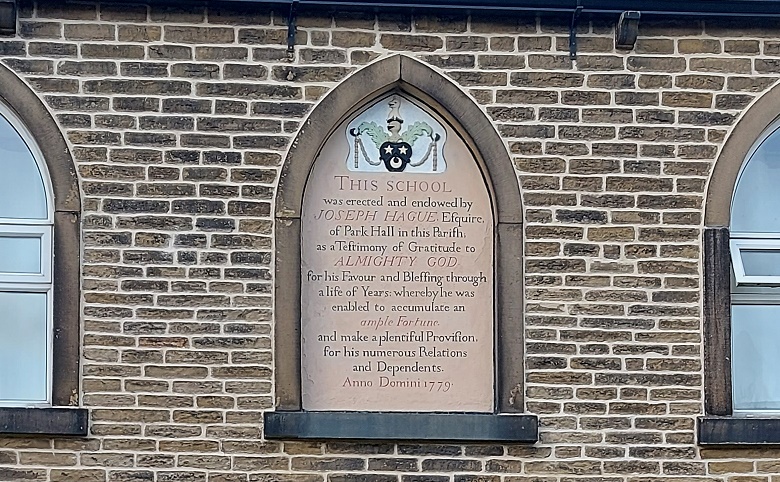

I’m not going to go into the history of the roads in the Glossop area, as it has been covered in detail elsewhere (Glossop Heritage Trust), but in summary. it is only with the advent of the Turnpike Roads in the late 18th and earlier 19th century that Glossop finally got some ‘real’ roads. These high quality, well built and maintained, turnpike roads were paid for by a private consortium which recouped the money by charging a toll to travel on them. The introduction of these toll roads changed Glossop permanently, as it meant that the vast economic potential of Glossop’s mills could be fully realised; prior to this, mills were restricted, as it was difficult to get your finished cloth out, as well as raw materials in. Once this was problem was solved, the full brunt of the Industrial Revolution could be unleashed, bringing with it all the positives, and negatives, of this turbulent time (and if you know me, the you’ll know I’m essentially a hobbit, and so I think it was all a huge mistake!).

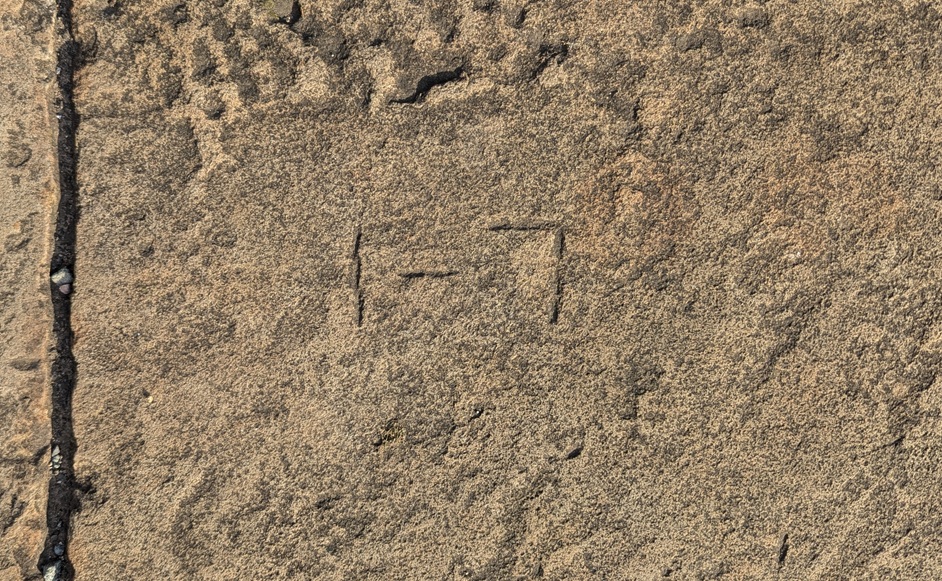

So, there I was, wandering down the bottom of Cliffe Road (in blue above), when magically, beneath my feet I saw this:

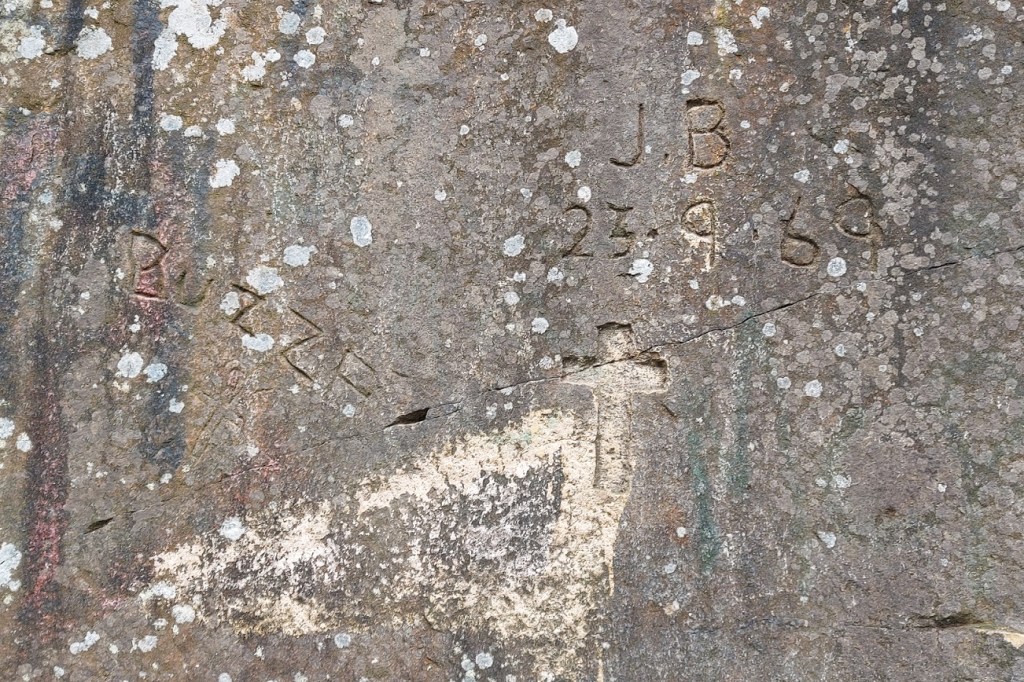

The woeful state of the roads here in north Derbyshire, had revealed the original road surface; ‘What ho, setts!’ I thought.

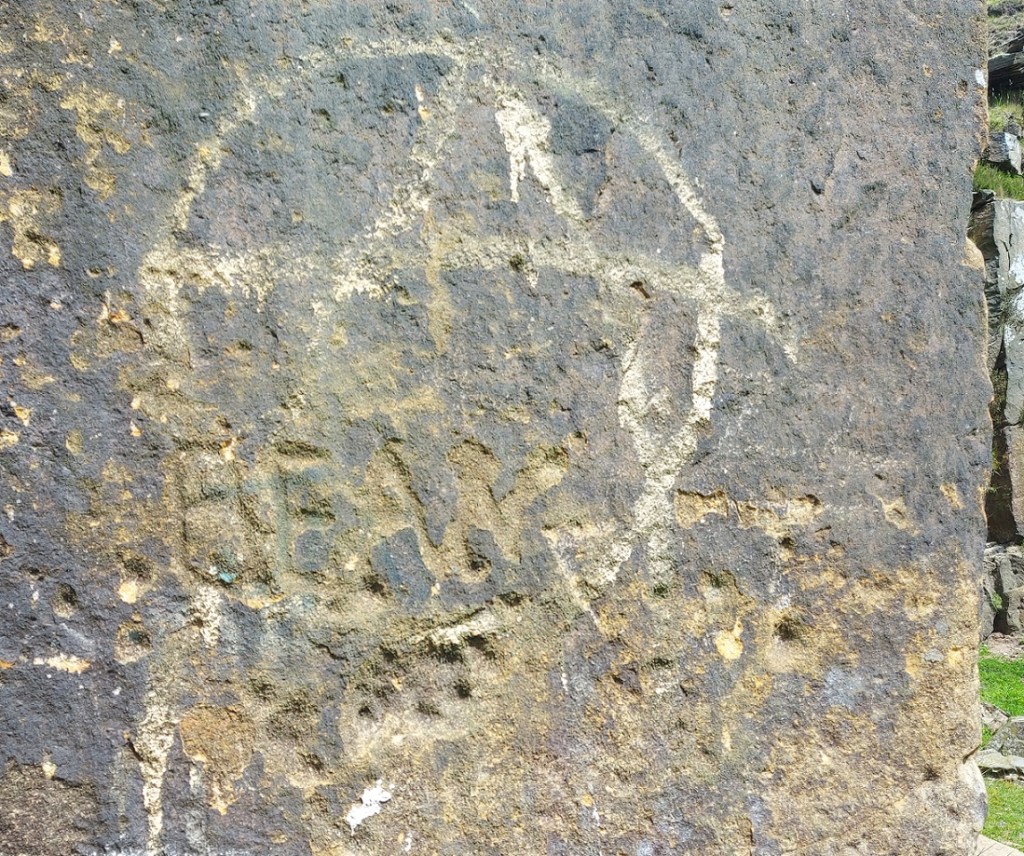

So what are we looking at? This is the original surface of the road, dating to the time when this sideways step was constructed in the early 19th century (the datestone on the house at the bottom there reads ‘1815’, which is perfect). These are the setts that made up the road itself – a sett, which is deliberately shaped by human hands, rather than a cobble which is natural product and can be picked up off the beach. The fact that each one of these was shaped by hand frankly blows my mind! What a tedious, tiring, and unpleasant job that would have been, day in, day out. And how many 100’s of thousands… millions, would have been used in Glossop alone? Frightening stuff.

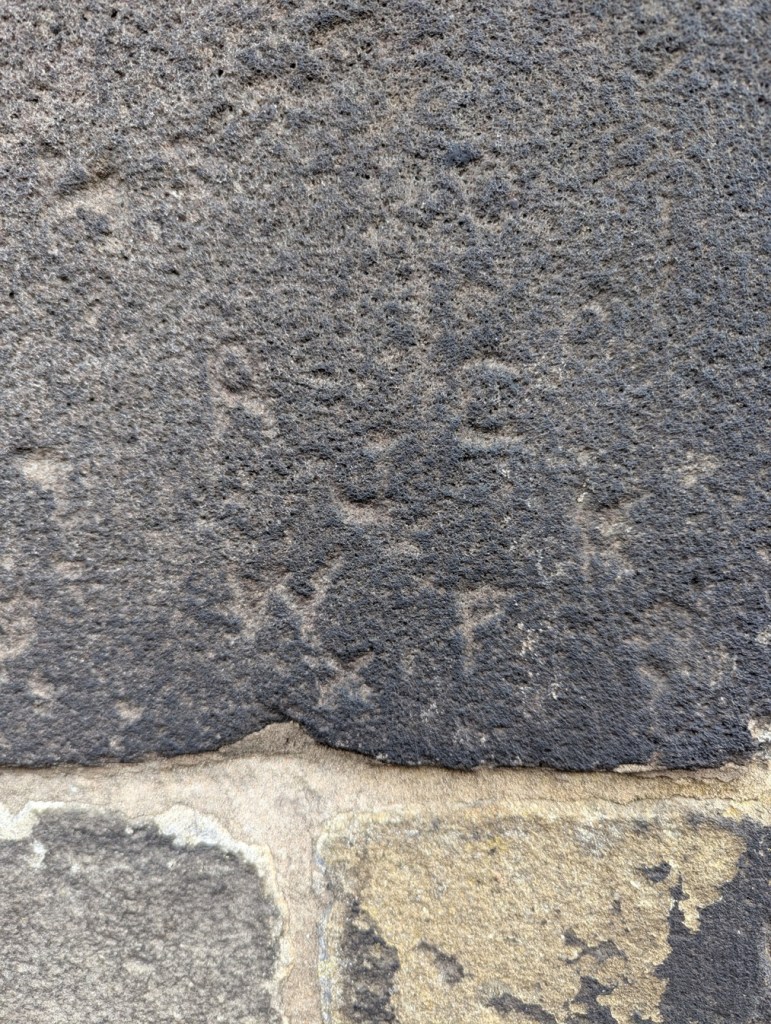

As you wander about Glossop, you can often encounter these sneaky little portals to the past, and I like to stand on them, imaging what stories they could tell. I also take photographs of them… what’s that? Hmmmm?… “I say, TCG old chap, you couldn’t show us some photographs could you?”. Well, I’m glad you asked, old bean, because I have few I could share!

The reason that we can see this is that the modern tarmac can’t get a good grip on the smooth surface of the Setts, and it simply peels of over time. They tried to solve the problem by scoring deep lines into the stone, but that doesn’t seem to have worked, either!

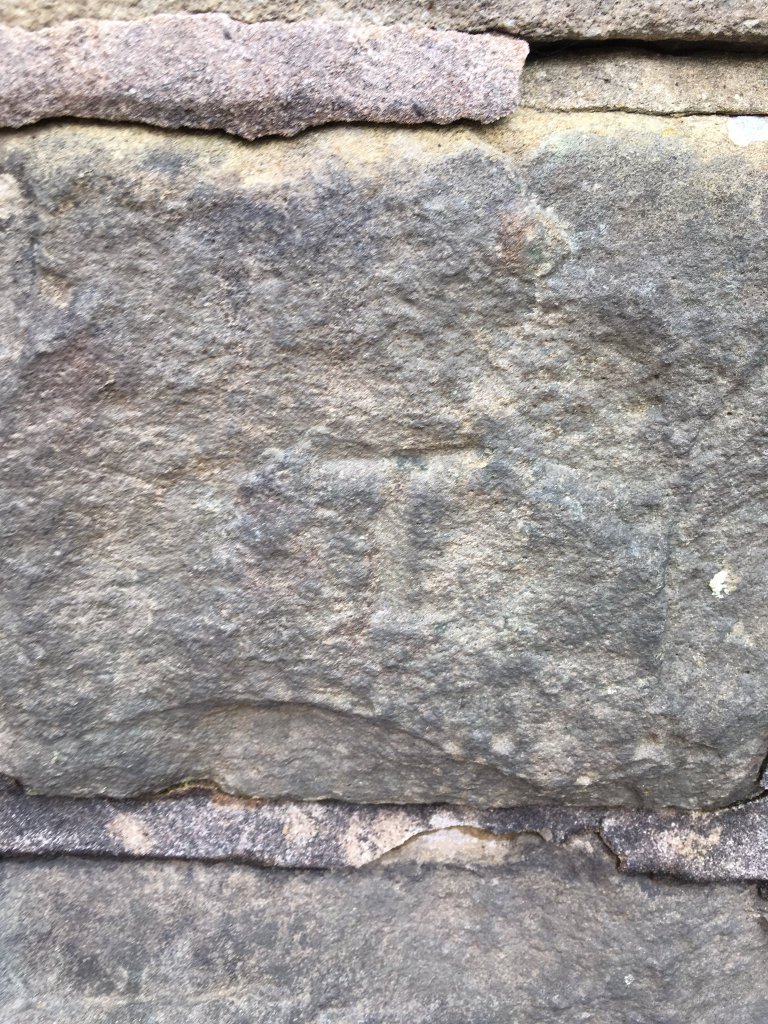

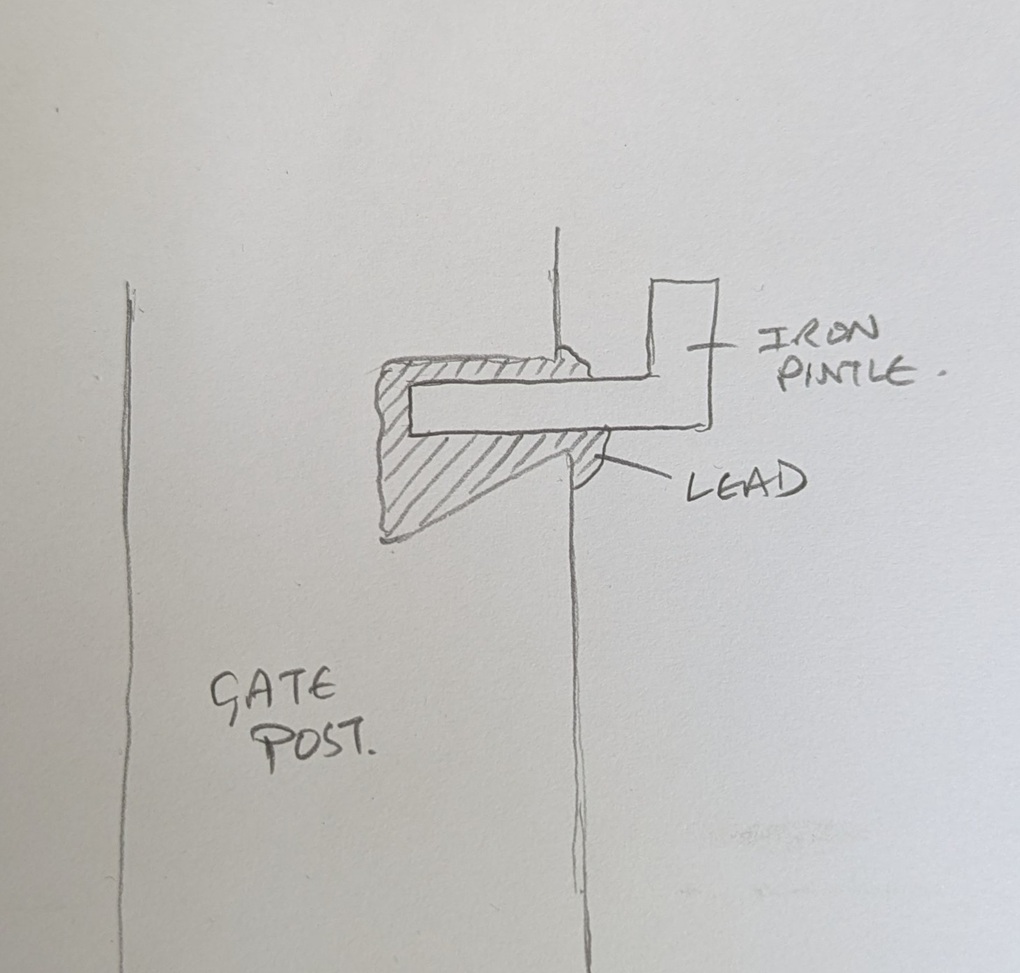

Occasionally, when there is a problem and the road need opening up, they have to pull up the setts, and you can can see how they were laid.

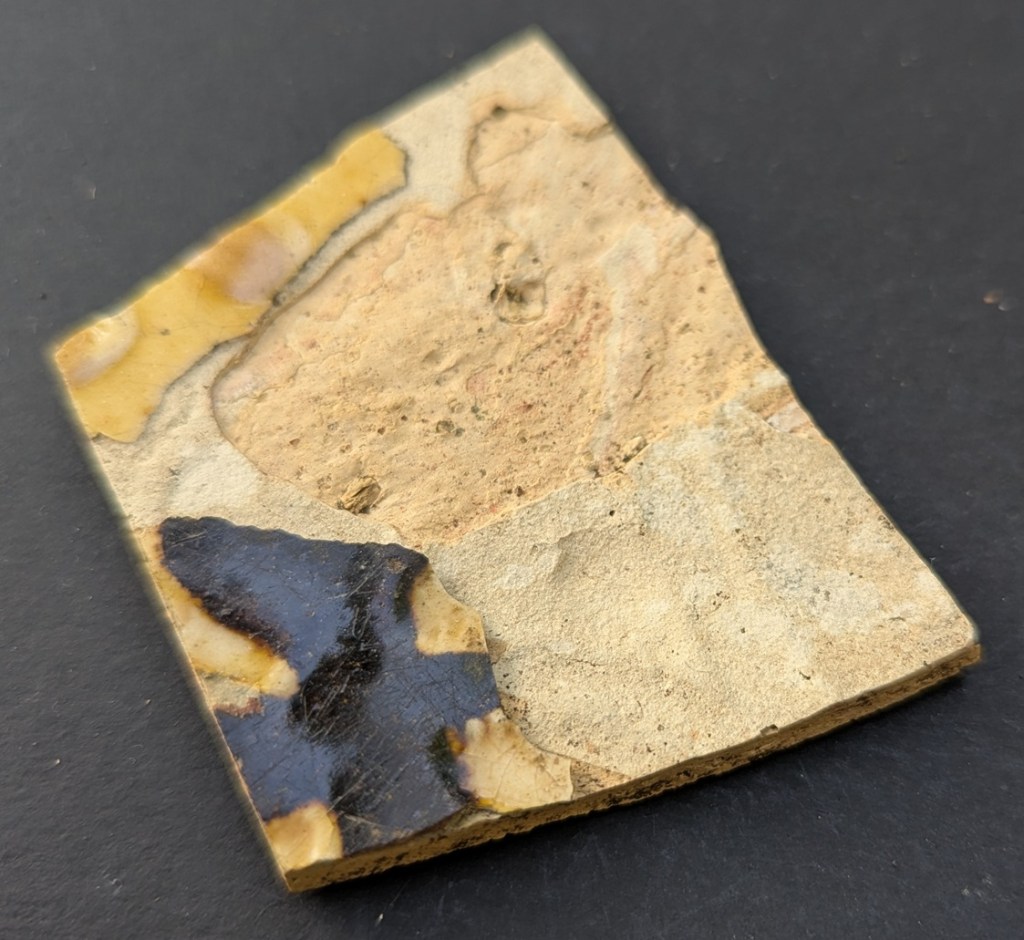

And, of course, you can sometimes get lucky with the spoil from these excavations, and find a piece of pottery… obviously you can’t have an article without pottery!

Also, this provides us with a terminus ante quem, meaning that the pottery could only have been deposited before the road was laid down, which is the case of St Mary’s was mid 19th century, or slightly earlier. Wonderful stuff!

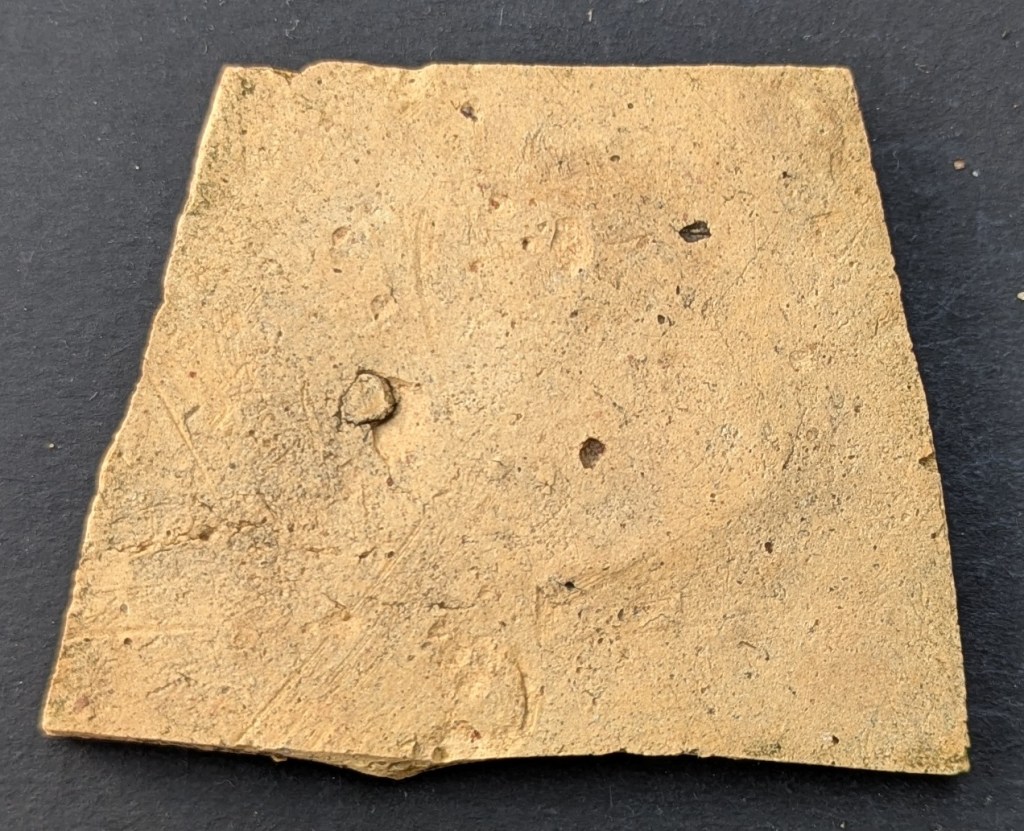

And of course, sometimes, the setts roll out of the spoil heap, and into… well, let’s not beat about the bush – my garden. It seems such a shame to just let them disappear into the truck and be driven off to a landfill somewhere, or to be used as hardcore for a new road. That saddens me greatly. So occasionally, they – magically – roll into the garden. Uphill. And sometimes over great distances. Following me home, if you will! And I can tell you this, they are heavier than they look!

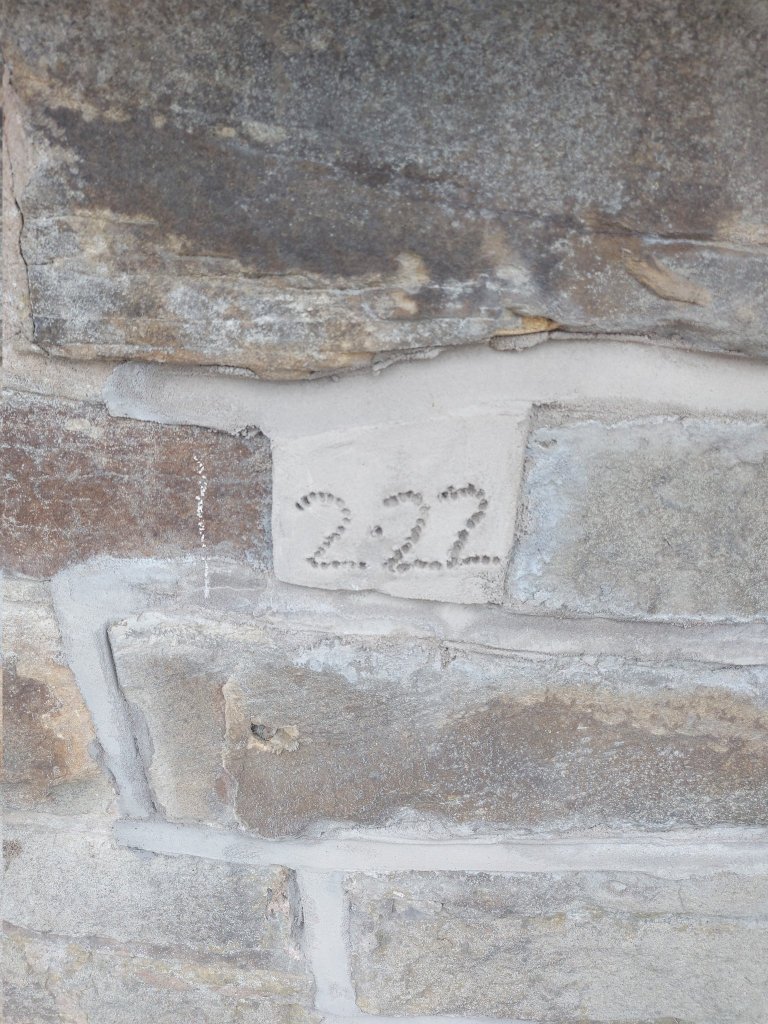

It measures 7″ x 4″ x 5″, and has a smooth even surface. Hamnett suggests that King Street was laid out in the 1840’s and 1850’s, which makes sense.

Measuring 7.5″ x 7.5″ x 6.5″, the Turnlee Road sett is bigger, and has a rougher surface. This one is older, too, as it was presumably laid in the 1790’s when the turnpike road was put through, and is thus a real piece of Glossop’s history: who knows who and what travelled on this surface.

The King Street stone seems smoother, and thus more worn, than the Turnlee Road sett. This is odd – surely Turnlee would have seen much more traffic than King Street? But the differences may be explained by the location of the stone within the road surface; King Street was taken from the middle, whereas Turnlee was, I seem to remember, came from the edge of the road, where presumably no traffic would pass. It might also be explained by different stones being used – the Turnlee stone looks almost like a hard-wearing granite, whereas King Street seems more like a local gritstone. But I admit I am no geologist, so if anyone knows any better, please do shout out and correct me.

These are not the pretty bits of archaeology; the fancy buildings, the lovely pottery, the flint, the burial mounds, the Roman fort. Instead, this is simply the nuts and bolts of it – a road surface. And yet it has that vital link to the past, that important accessibility, that allows us a glimpse underneath the modern, and for that, I find them endlessly fascinating.

Right-ho! That’s all for now. My only New Year’s resolution this year is to publish more on the website, but to make the articles smaller, and thus quicker to write. I have another almost written, so I’ll go with that soon, and I’m working on all manner of other things, too.

Until then, though, look after yourselves, and each other, and please do get in contact with any thoughts or comments.

I remain, your humble servant,

TCG