Mrs Hamnett complains that going for a walk with me is difficult – apparently I’m like a dog, running about looking for things. We’ll be walking along, talking, and I’ll disappear into a hedgeback or ditch, pulling out a bit of pot or stone, and leaving her talking to herself. Master Hamnett has now adopted the custom, and he regularly finds bits of pottery that he hands to me, looking very pleased with himself. This leaves small piles of pottery around the place, which get cleaned and put into bags with the intention of sharing them with you, gentle reader. And as you know, intention and actually doing are two widely different things – I’m going to have “well, I was going to, but what happened was…” carved on my headstone.

Well, not today. Today I do! I am seizing the day, grasping the nettle, taking the bull by the horns, striking whilst the iron is hot, and a host of other tired cliches. Today is a pot and other bits day… but first a cup of tea.

Right, that’s better! Off we go.

A few months ago I posted this, a toy soldier fund by Master Hamnett at the Spencer Masonic Hall/Sunday School at the top of Whitfield Avenue. Well, we went back recently, and blow me… we found some more.

Bizarre. I can only think that someone was using this as a place to play with their soldiers, and then lost them. As I said before, these were my childhood (I still have them). From right to left: a 1:32 scale Airfix British Commando (mid 1970’s to, well, now in date). Then we have a copy of a 1:32 scale Airfix British 8th Army Desert Rat; it says ‘Made in Hong Kong’ on the bottom, which dates it to pre-1997, when Hong Kong became Chinese. Then there is the lower half of Marvel’s Iron Man, which has the date 2005 on the base. I suppose these are technically ‘rubbish’, being deposited only in the last few years, but I reasoned that if I picked up a Victorian child’s marble, then why not these too. If you recognise them, and want them back, give me a message. Above the toys is a squashed thimble, again probably of relatively recent vintage.

Some other bits and pieces found in the grounds:

From the top down, then. Randomly, fragments of a clay pigeon – which begs more questions than it answers. This is definitely rubbish, and will be going straight in the bin, but I thought I’d post it in the interests of completion. Below that, a copper roofing nail – Victorian or early 20th Century, and clearly from the roof of the building, dropped during a re-roofing, perhaps – I love these things, and have blogged about them previously. Below that, an ‘L-Headed’ machine cut wrought iron nail – probably used for flooring, and perhaps Victorian.

Continuing the revisit of that post, here is some more pottery from the area:

Some odds and ends. Top row, from left, then: the bottom of a jar of some sort – earthernware, and with the letters ‘A’ and ‘D’ impressed on the bottom. It’s possible this is ‘MARMALADE’, as it’s the right type of jar, but I don’t think it’s an ‘L’ before the letters. ‘M[AD]E IN ENGLAND’, perhaps? Next a saucer, then a black glazed open vessel, and then the chunky handle of a jug or similar, but certainly not a tea cup, the handles of which were delicate in the Victorian period, which is when all of this pottery dates from. Bottom row from left: a creamware jug, and from the curve of the sherd, this the rim of the spout; early Victorian, at a guess. Next, the base of an open bowl, then the interior shoulder of soup bowl, the base of a plate (complete with knife mark scratched into the glaze), and then the shoulder and neck of a small saltglazed stoneware bottle. Originally, it looked like this one, probably an ink bottle, and which has roughly the same dimensions:

Next up, we have some interesting new bits from below Lean Town, picked up whilst I was waiting for Master Hamnett to finish at the excellent Inside Out Forest School in Gnat Hole Woods, not too far from Nat Nutter, as it happens.

Top row: sherd of earthernware with painted orange flowers, which I thought looked nice. Then we have two different shell-edge ware vessels decorated a blue scalloped edge. The one on the right is the earlier, being made between 1780 and 1810, whilst the sherd on the left was made between 1800 and 1830. Then a sherd of annular or banded ware – the decoration looks very 1950’s to modern, but this stuff – usually in blue (there is an example below) – actually starts being made in the 1790’s. This one is Victorian. Second row on the left, a base sherd from a basalt stone ware bowl, roughly 1780-1830-ish, It’s a lovely example, very thin walled and with the bottom of an acanthus leaf or something coming up from the bottom. They were heavily influenced by Classical pottery, and it looks Roman orAncient Greek from a distance, but was in fact made by Josiah Wedgewood’s factory in Staffordshire. Then we have the handle to a monstrous stone ware jug or storage jar, and although it looks almost medieval, it probably came from a Victorian water jug or something. Following on from the mega post about Lean Town I’ll add this lot to the bag of bits, and I’m sure more will wash out over winter.

Moving on, we have a rim sherd of a pancheon and another sherd picked up from a path that leads from Bankswood Park in Hadfield to Mouselow.

The smaller sherd is a from a cup or bowl with blue horizontal stripes on a white background – more annular or banded ware from the Victorian period. The larger sherd is part of the rim from a large pancheon – essentially a large mixing bowl that most kitchens in the 18th and 19th centuries would have had (I talked about them here). What looks like a yellow glaze is actually a clear glaze over a white slip – you can just about see it on the edges. Below is what it would have looked like, although this example is later and much smaller, the rim sherd suggesting a vessel 70+ cm in diameter.

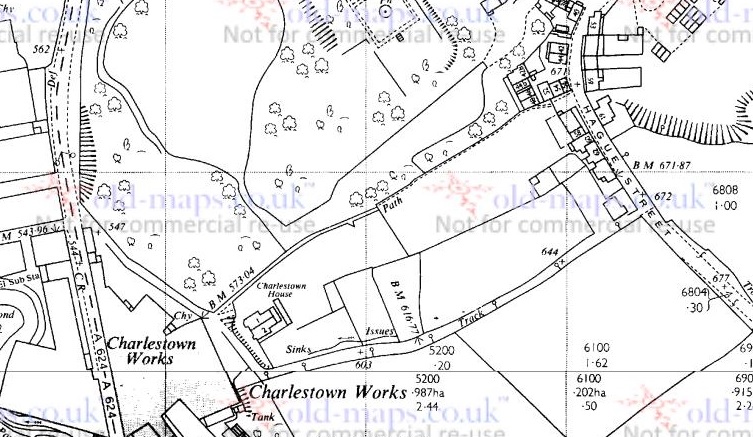

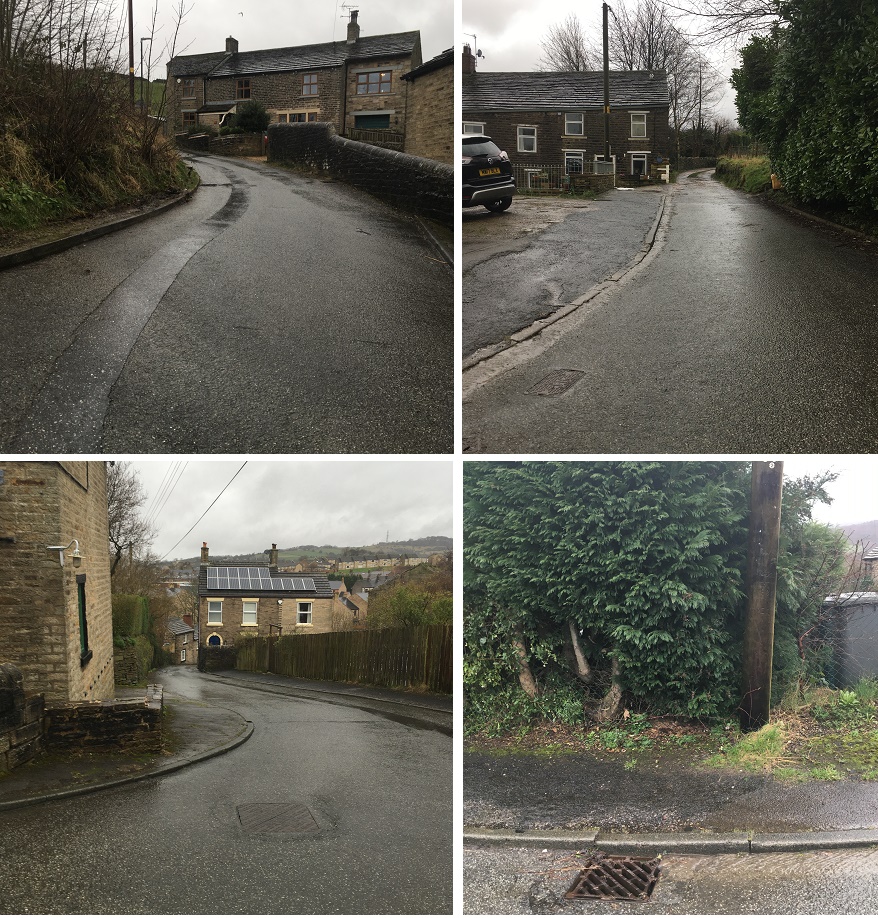

The path crosses another track which originally ran from Cemetery Road to Shaw, along what would become Shaw Lane, before it was bisected by the building of the railway.

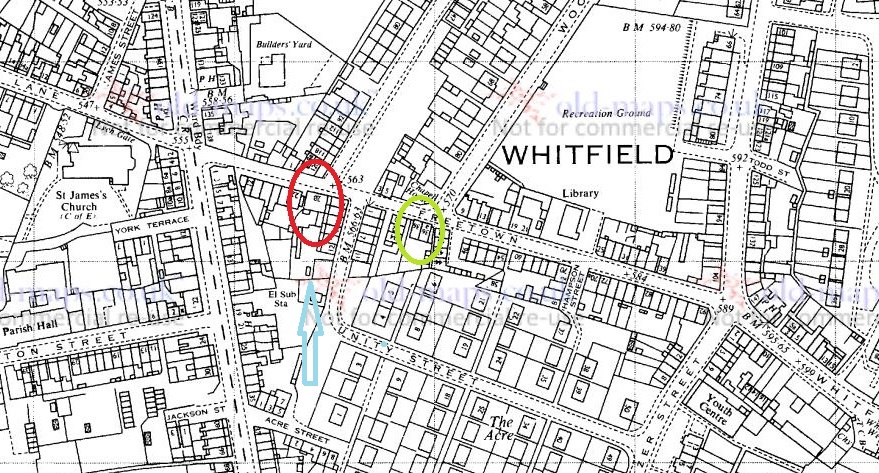

The lane actually skirts the edge of the Iron Age hillfort, and parts of it are preserved in footpaths and tracks, but I don’t want to get into this here, as it is a topic of another post. However, here are some photos of Shaw Lane as it crosses Mouse Low – the above pot fragment was found at this junction with the footpath, marked in red on the map.

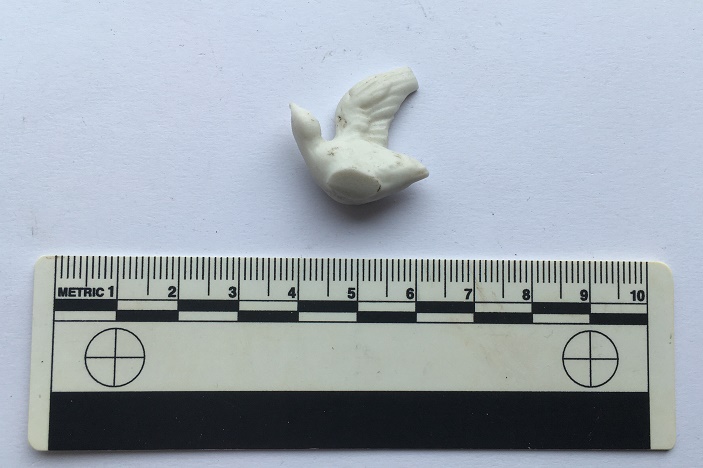

Next we have a small collection of bits from the bottom of Cross Cliffe, along the road edge and by the track there. Nothing earth shattering, but a good selection.

Top row, from the left: a fairly substantial transfer printed soup bowl roughly 20cm in diameter; the base to a ceramic marmalade or preserve jar of about 10cm in diameter; a stoneware sherd from a storage jar of about 16cm in diameter. The thing that looks like a mint is either a button or the end to a hat pin, and is made from alabaster. Next row: sherd from a large jug or similar, with large hand-painted flowers on the exterior; rim of a stone ware ginger ale or lemonade bottle, with the very characteristic brown salt glazed surface; a fragment of willow pattern transfer-printed plate, and a stem of a clay pipe with, alas, no maker’s name, but some nice paring marks.

Ok, so this is turning into a far larger post than I had anticipated, and I’m going to draw a line under it for now – nobody, not even you, you wonderful and attentive people, wants to read a wall of text. Expect Part II either next time, or sometime in the future

So, to end with, for now at least, two superb examples of Glossop bricks, a gift from our equally superb neighbours (hello Helen and Sarah).

I don’t know a great deal about these bricks, but a future blog post might delve deeper. The company was based at Mouselow, with the clay extracted from nearby. It seems to have been founded in the 1920’s by a John Greenwood, and continued until the 1980’s. Somewhere in the garden I also have Glossop brick with both Greenwood’s name and Glossop printed on it – perhaps this was an earlier brick? There is some information on this website, but I can definitely feel a blog post coming on.

Bricks are so mundane, and yet so fascinating, and useful archaeological dating material too. And once they begin stamping the maker’s name into the frog (the dipped bit in the middle) – sometime around the mid-Victorian period – they become individual, too. I stumbled across this website the other day – a gigantic collection of photographs of bricks with the names showing, and all alphabetised; this is what the internet excels at, the dissemination of knowledge that would otherwise be inaccessible, and it is truly magnificent. I look upon these bricks with envy, but silent and certain in the knowledge of one single fact: were I to start a ‘brick collection’ Mrs Hamnett would forcibly and violently eject me from the marital home. I would be a single and homeless (and brickless) man again before you could say “now wait, dash it all”. No, she puts up with quite enough as it is, so this injustice and pain is a weight I must bear with quiet resignation. However, if someone does have a spare shed, you can contact me in the usual way…

Right, that’s your lot! And it is a lot… too much, in fact! The question of “what am I going to with it all” never really occurs to me, and beyond the obvious “put it on the blog” I have no idea. I’m going to have a clearout soon, and get rid of the more boring bits and pieces – the plain white china, etc. and bury them somewhere for future archaeologists to ponder over. In fact, I was going to do it last week, but what happened was…

More soon, but until then, take care of yourselves and each other.

And I remain, as always, your humble servant.

RH