A brief blog today…

Mrs Hamnett, Master Hamnett, and myself found ourselves passing through Macclesfield a few weeks ago. So I took the opportunity to visit the three splendid Mercian Round Shaft crosses that were erected in West Park there. I had tentatively suggested that one of them was a dead ringer for Whitfield Cross, and in a slightly better state of preservation. Definitely worth a closer look, and, of course, Master Hamnett was pleased as it means he got to go to the park.

The three cross shafts are located in the middle of the play area, and impossible to miss.

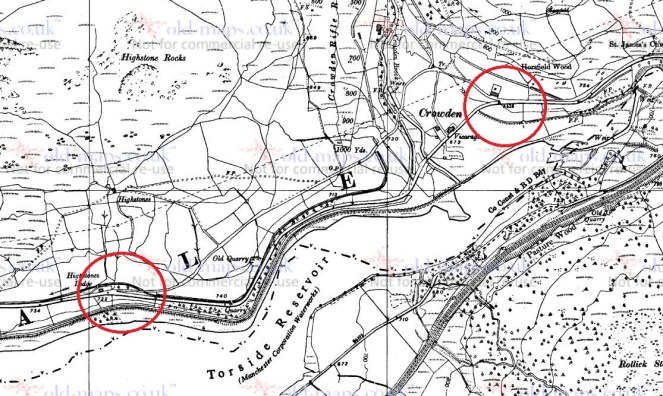

They were originally sited together at Ridge Hall Farm in Sutton (about a mile south of Macclesfield – here). Two of them were being used as gateposts, with iron and lead fixings carved into the stone, and the third was in a pile of rubbish. Their importance recognised, they were promptly moved to West Park, arriving there on 7th January 1858. Interestingly, Ridge Hall Farm was originally a moated farmhouse of medieval date – the remains of the moat can be seen in the aerial photograph above, circling the farm at the south and west.

Now, although the crosses were ‘found’ together, I don’t think that the farm was their original site, and it is likely that they had been moved there from points unknown. The probability of their movement is given evidence by the fact that the farmer had two cross shafts on his land, exactly the right width and in exactly the right location to form a useful gate. And by the fact that one of the crosses was “in a pile of rubbish” – such wording suggests it had been moved and discarded, perhaps awaiting employment as a fence or gate post. Also, whilst they occur in pairs (and the gatepost pair may well be an example of this), we know of no other examples of three crosses occurring together. However, caution should perhaps be urged here; with so few examples of this cross type surviving, we don’t have a huge body of evidence from which to draw comparisons or to make bold statements, and as the old archaeological dictum runs, absence of evidence in not evidence of absence. But in this instance, and on balance, I think it is likely they had been moved. Given that Ridge Hall Farm is not near any parish boundary, nor is close to a church, we might tentatively suggest that they originally marked the junction of tracks, as Whitfield Cross once did.

But I digress.

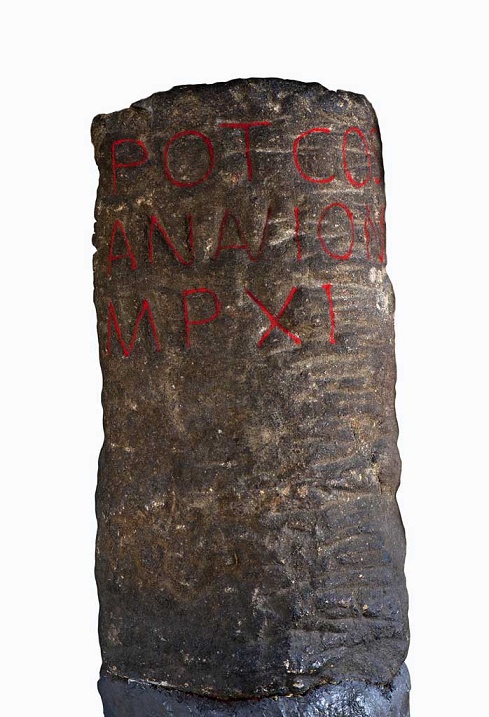

The one that resembles Whitfield Cross is on the left of the three in the above picture. In the Cheshire and Lancashire volume of Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Sculpture (website here) it is listed as Sutton (Ridge Hall Farm) 1, and dates it to 10th or 11th Century. Here is a close up.

Although it is made of a similar stone, it is unclear if the cross base is original to the cross. I have to say, it looks like it might be, and if it is the case then we might suggest that this cross was in its original position on the farm. The other two crosses don’t have their bases, and it seems doubtful that the farmer would go to all the trouble of digging up the cross base, when he could just sink a hole and place the shaft that way. Also, if the other two had their bases, then the 19th Century antiquarians who were responsible for their movement would have taken them too.

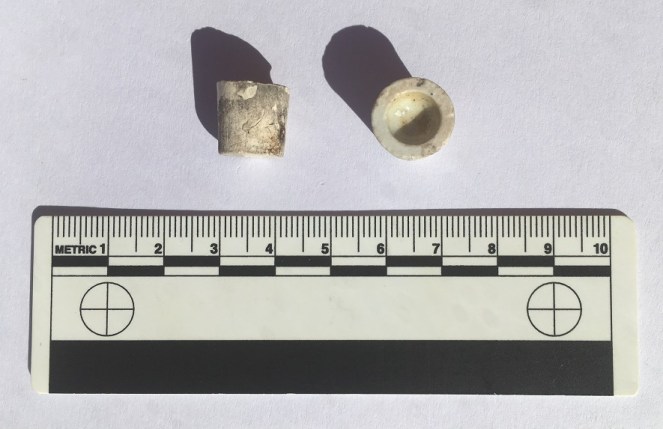

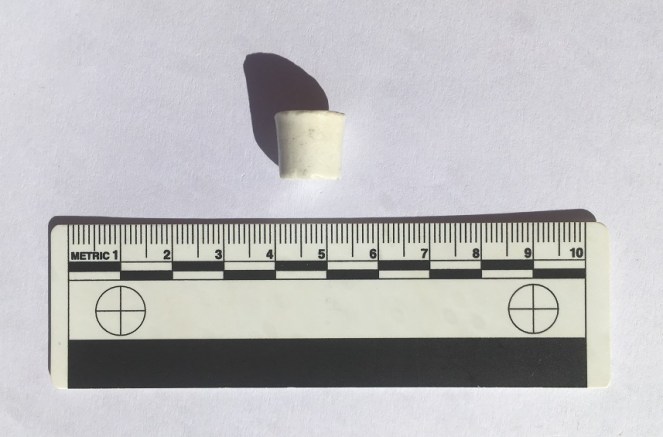

The collar is of a very similar style to Whitfield – sloppily executed with a rough groove drawn around the neck, rather than two distinct bands.

I also suggest that the decoration which is missing from Whitfield would be of a similar nature to the Macclesfield example. Here is a closeup of the decoration. You can see what remains of decoration on the Whitfield example above and below.

So there you are. This is what I think a little better preserved Whitfield Cross would have looked like had the puritans and drunken louts of the 18th Century not got hold of it. Having said that, I recently read about people digging up roadside crosses because they believed treasure was buried beneath them, which is another reason these crosses are so rare. Bloody barbarians!

Anyway, I know this is a long way from Glossop, but I think it is important that the comparison with Whitfield Cross is made and explored… who knows, the same craftsman or woman may have carved the crosses. And it’s interesting nonetheless.

Next time, I’ll be a lot more local… very local indeed.

As always, any comments and questions are welcome. There really is quite a thriving community of people out there, and it’s great to hear from you all.

Your humble servant,

RH